October 9, 1917 - April 24, 1943

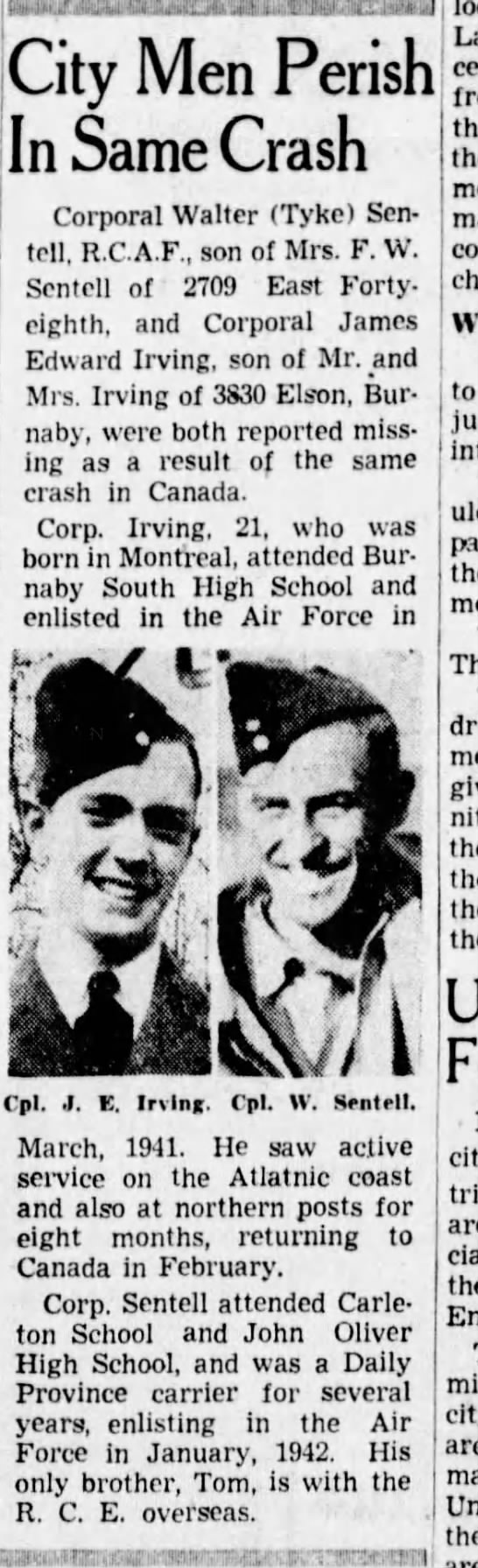

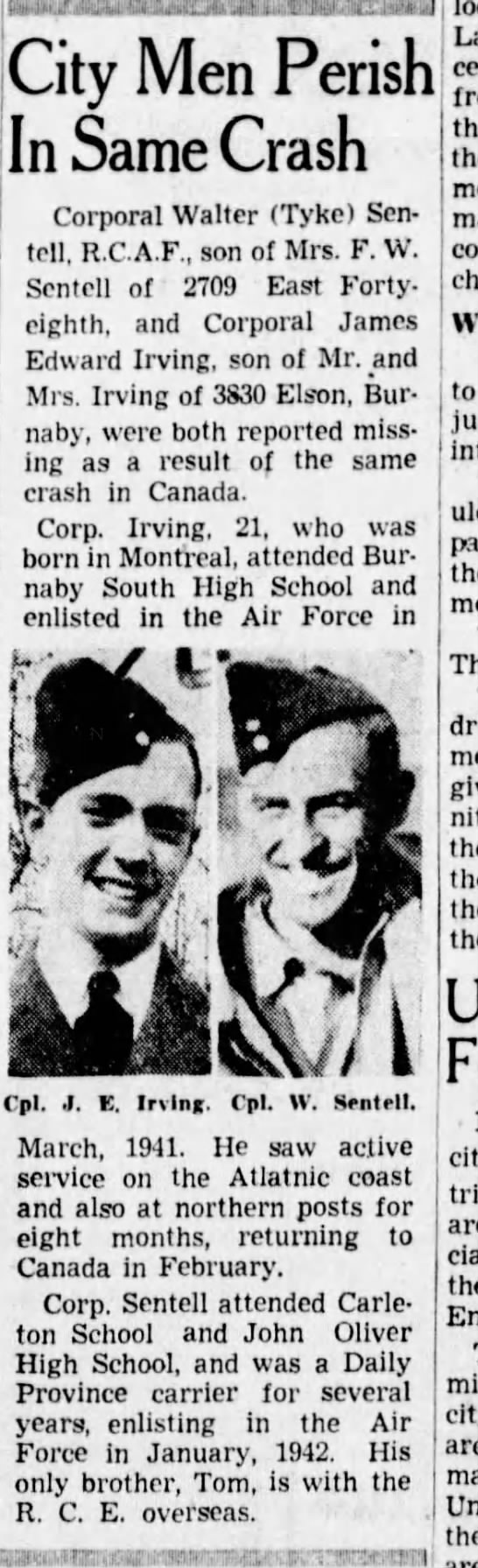

Walter Sentell was born in Vancouver, British Columbia, son of the late Frederick and Jane Sentell. He was brother to Thomas, who served during the Second World War with the Royal Canadian Engineers.

Walter stood 5’8” tall and weighed 134 pounds. He had blue eyes, sandy hair and a fair complexion. He liked to bowl, ice skate, and swim, plus participate in all sports with the exception of football. He enjoyed listening to classical music and reading Readers Digest magazines. He had his junior matriculation.

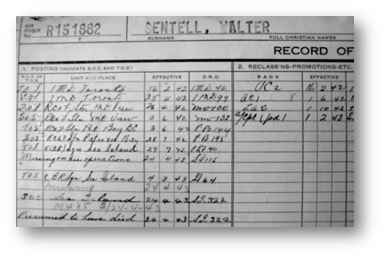

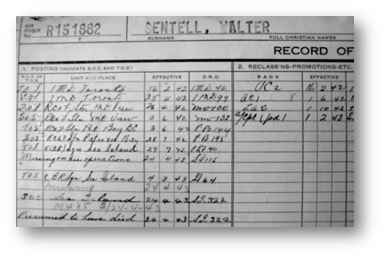

In Vancouver, he was an apprentice at an auto fabrication/autobody shop as an auto trimmer, plus worked on the tops and upholstery. He also had experience with radiator repair. He indicated that after the war, he wanted to work in a government job, preferably Customs. Walter enlisted with the Royal Canadian Air Force in February 1942 and was at No. 1 Manning Pool until April. He indicated he wanted a trade so as not to leave his mother, a widow, without support.

He was sent to Mountain View, Ontario as ground crew, then to Patricia Bay, BC. In June 1942, “NCO caliber. 17/35 in class; average. Intelligent. Hardworking airman. Appears steady and capable.”

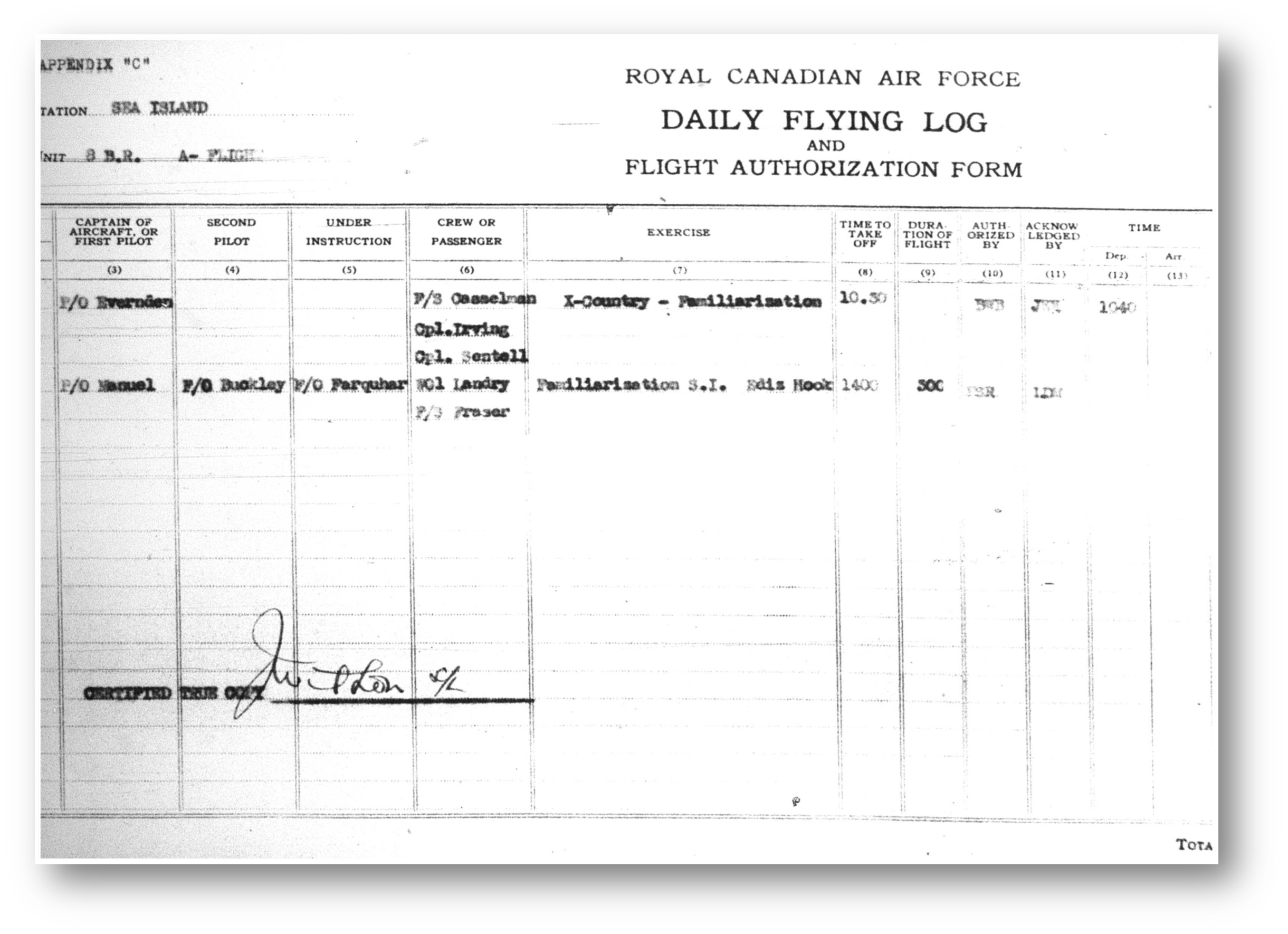

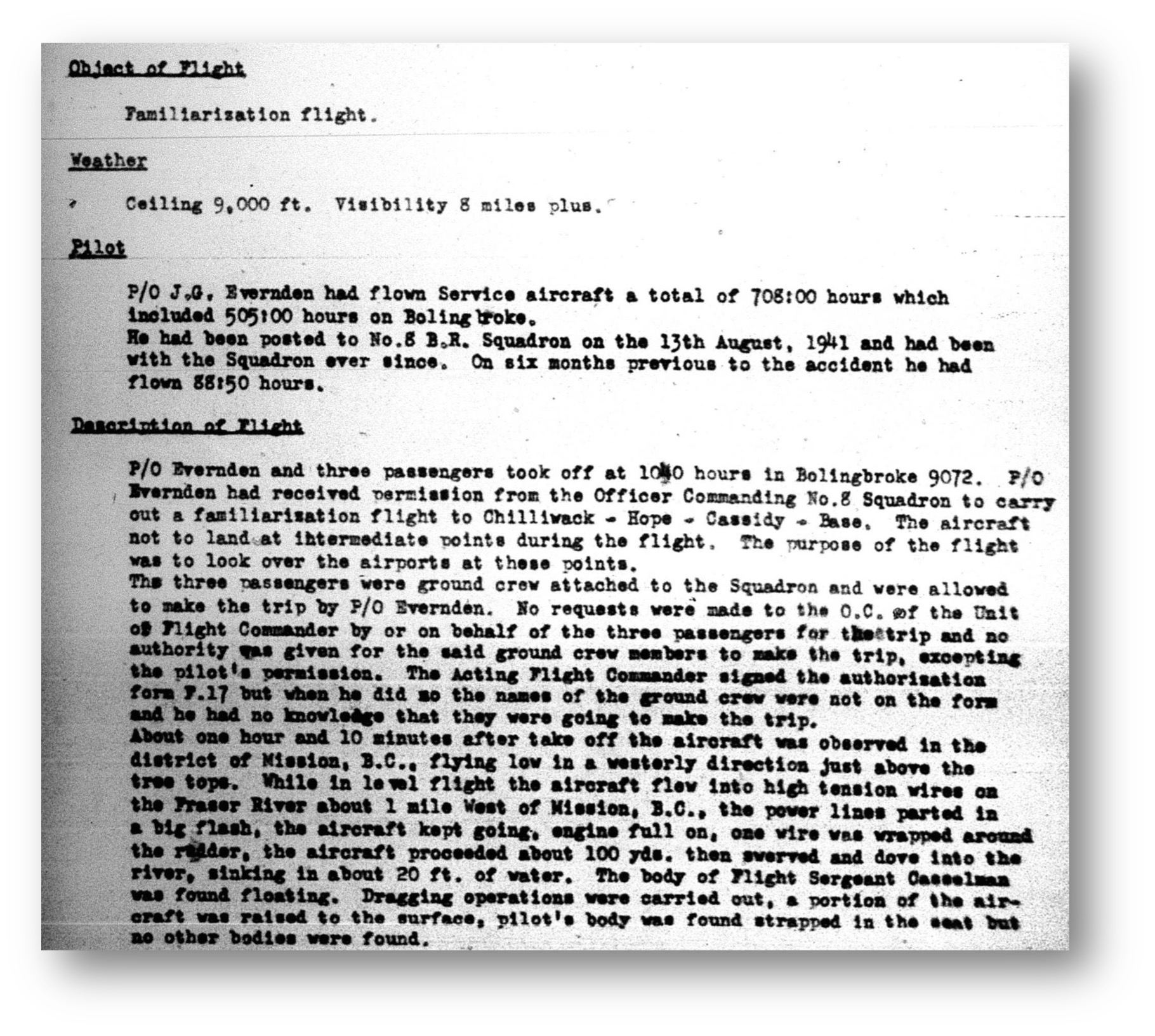

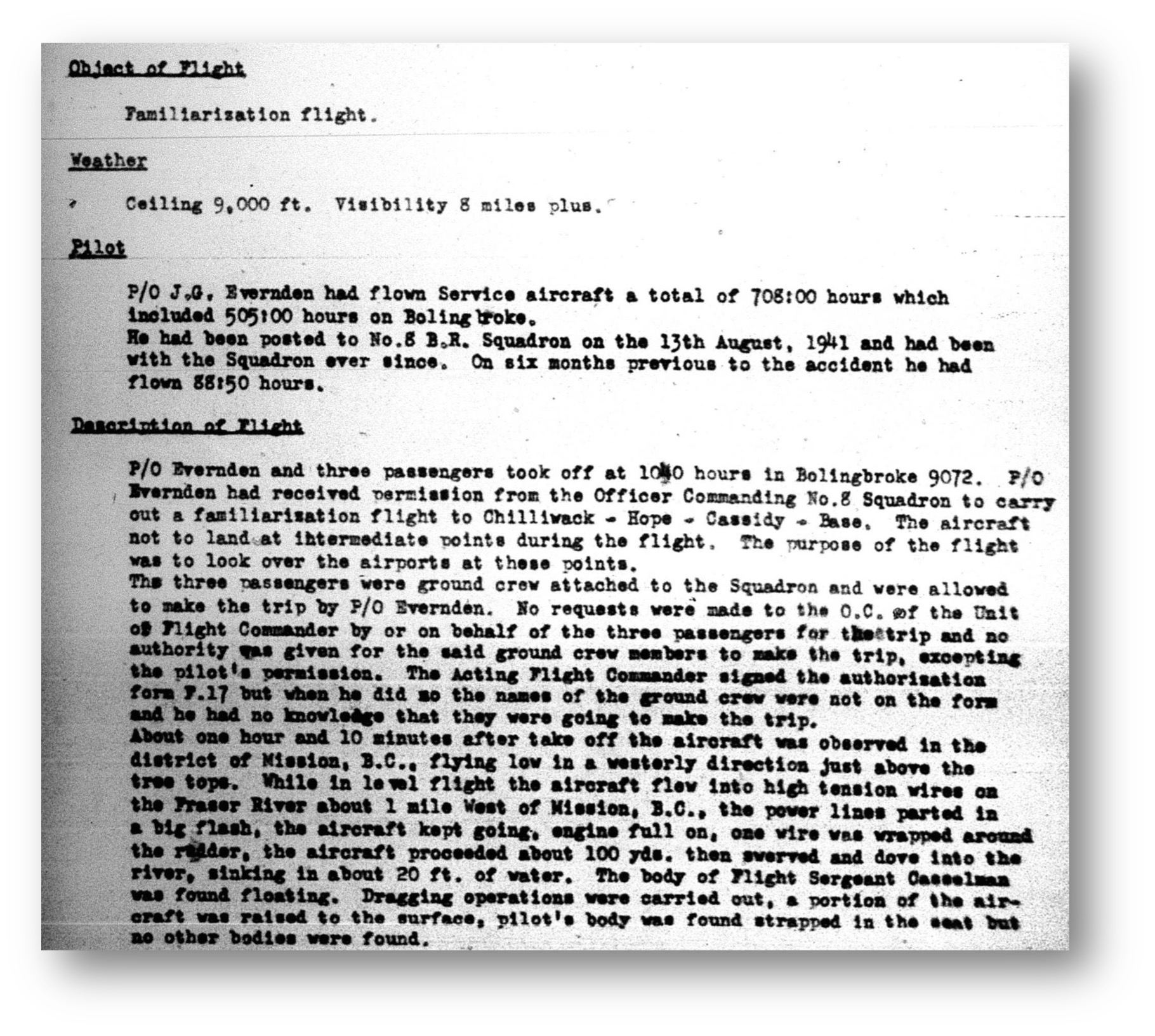

From August 1942, he was in Anchorage, Alaska, and then was sent to Sea Island by Mach 1943. On the April 24, 1943 familiarization flight, Walter climbed aboard. His body was never recovered after the crash. Bolingbroke 9072 suffered engine failure and crashed into the Fraser River, one mile west of Mission, BC. CREW: P/O Jesse Evernden, F/S Donald John Casselman, Corporal Walter Sentell, and Corporal James Edward Irving.

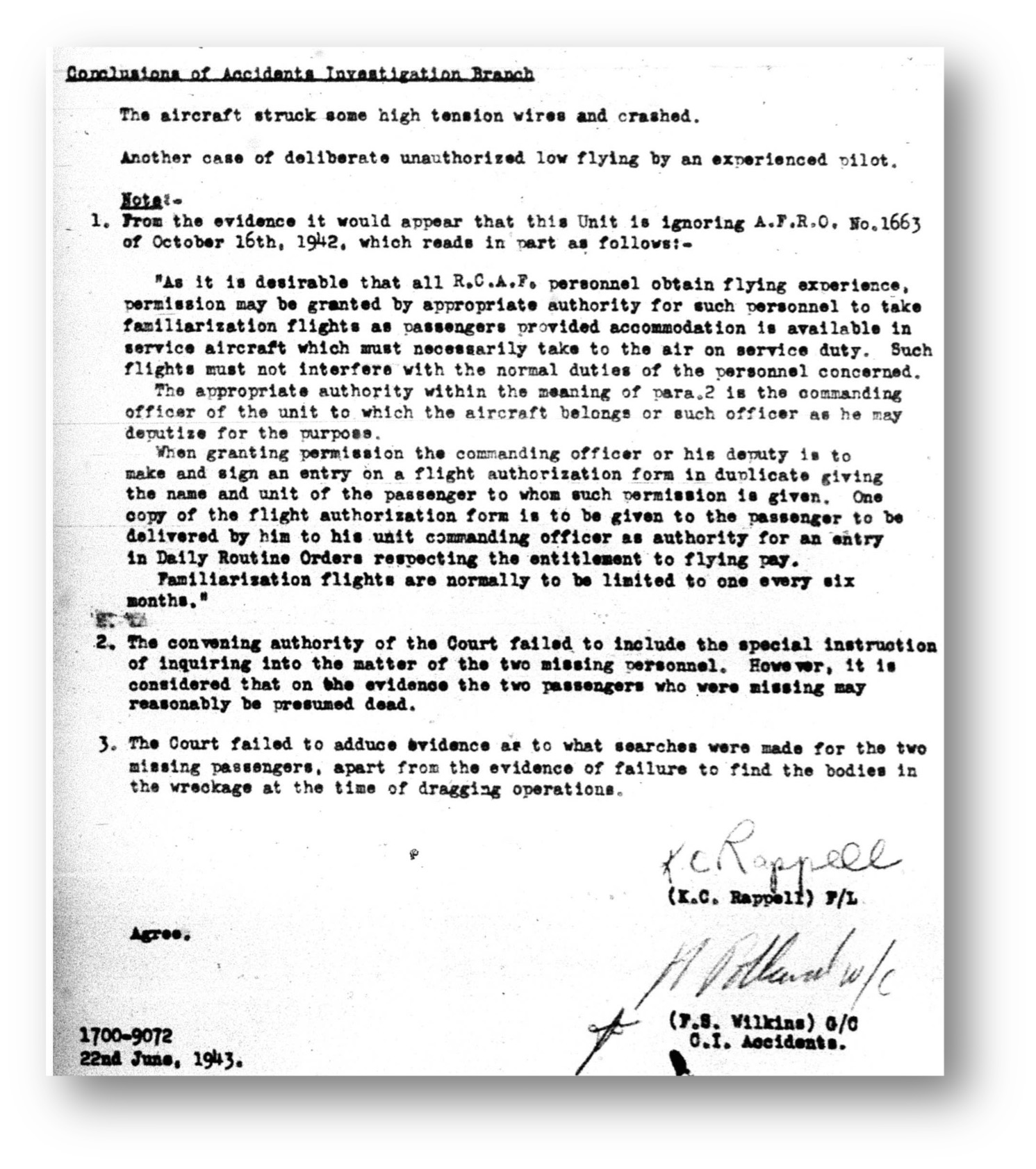

The following is a summary from the Court of Inquiry.

A Court of Inquiry was assembled by order of the Air Officer Commanding, Western Air Command. Some members proceeded to the scene of the crash in the afternoon of April 24th, 1943, the same day as the accident. “This party proceeded by air together with the Chief Engineering Officer of this Station, the Officer Commanding No, 8 Squadron and the Station Medical Officer,” states a letter dated April 26, 2932, addressed to The Secretary, Department of Nation Defence for Air in Ottawa. No. 3 Repair Depot, Vancouver would undertake the salvage operations, but they were hampered because of the “very swift current and the muddy water.”

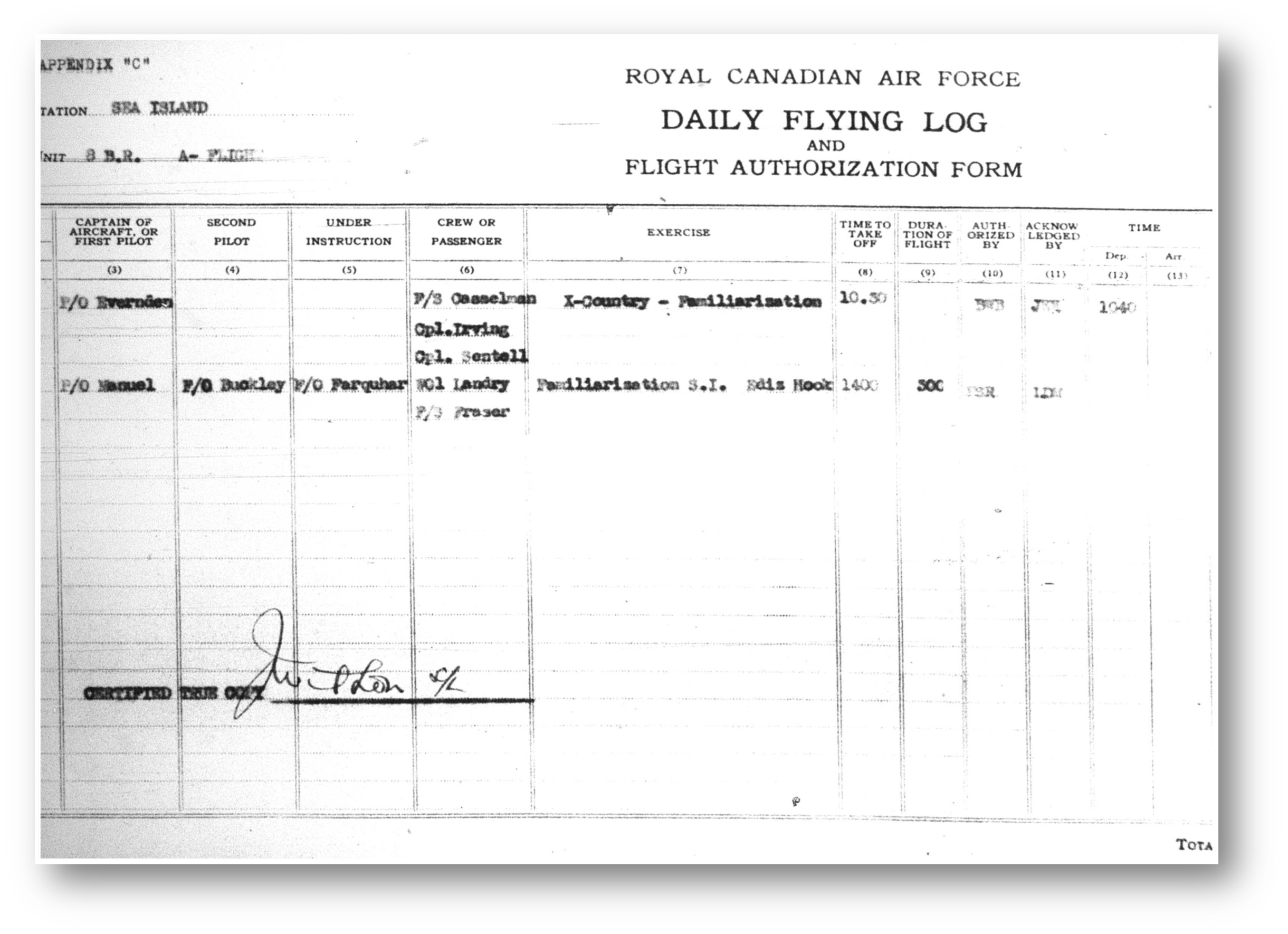

The first witness to be called was F/L John Carleton Wade, Officer Commanding No. 8 (BR) Squadron, Sea Island. “On April 24, 1943, at approximately 0930 hours, P/O Evernden approached me in my office requesting permission to carry out a familiarization flight to Chilliwack, Hope, Cassidy, and return to Sea Island, the aircraft not to land at intermediate points during the flight. The purpose of the flight was to look over the airports at these points. I presumed that he would carry a normal crew and so gave my approval verbally. At approximately 1230 hours, Operations called and advised about the crash that had been reported near Mission, BC and that P/O Evernden was overdue. It was thought that Bolingbrook 9072 might be involved. I immediately proceeded to the Station Operations Room in company with the Station Commander G/C W.E. Bennett to obtain further information. On instructions from the C/O, I accompanied the Court of Inquiry to the scene of the accident, which was approximately 1 ¼ Miles west of Mission, BC on the Fraser River.” He further testified how P/O Evernden did not have authorization to carry out low flying on this flight, nor was given instructions regarding altitude in which the flight was to be carried out. F/L Wade felt P/O Evernden was a fully qualified pilot. Discussion continued about why the normal crew was not aboard, “As it is customary for the normal crew to be carried on flights of this matter and when requesting authorization, the pilot made no mention that he intended to carry three passengers instead of crew. On a practice cross-country flight, ground crew are sometimes carried as passengers but it is customary to carry a wireless operator.”

The second witness, F/O Beverly Ward Bristol, Deputy Flight Commander A Flight 8 BR Squadron said he authorized P/O Evernden’s flight, not knowing why the request for authorization went through him instead of the acting Officer Commanding. He signed the flight authorization form. He added, “I was not aware that the normal crew were not being carried and that the crew only consisted of the pilot and three ground crew passengers. The names of the passengers were not filled in on the papers I signed. It is necessary to carry a radio operator on a cross-country trip of this nature.”

Henry Ralph Willcox, Skipper of the “Timrah” tug, employed by Mission towing company, Mission BC testified, “On April 24, 1943 at about 1200 hours, I was towing a log underneath the high-tension lines on the Fraser River directly west of Mission BC. I saw an airplane flying low along the river from the east. I tried to wave and warn him of the high-tension wires, but he hit them immediately. The power lines parted in a big flash and the aircraft kept going, engines full on, and I noticed one wire was wrapped around the rudder. The plane kept going along the bank about 100 yards then swerved then dove into the river. I let go my log and came back to get any assistance I could. We found the inflated dinghy and one body floating, which we salvaged. I looked around for more bodies but did not see any sign of them. The British Columbia Provincial Police (BCPP) had then arrived on the riverbank, and I reported to them. I had not noticed the aircraft prior to just before the crash and no pieces flew off the aircraft.”

Donald Thompson, a municipal police officer at Mission BC stated, “At about 1150 hours, I was standing at the bank of my house which is situated about one mile west of Mission, BC, when I noticed an aircraft flying low along the river in a westerly direction. He hit the high-tension wires almost immediately, and the aircraft veered to the right, dragging wires with it. When the wires broke, he veered to the left and went straight in. The engines appeared to be performing normally prior to hitting the high-tension wires and no pieces flew off the aircraft.”

Robert K. Leighton, the constable in charge of the Mission, BC detachment of the BCPP was sitting in the police station when he saw an aircraft flying west at a very low altitude, just clearing trees on river flats. The phone rang notifying him that an aircraft had crashed where he proceeded to the scene. “Upon arrival, I contacted the skipper of the ‘Timrah’, Mr. Willcox. I went aboard and we went to the spot where the aircraft had crashed. One body [twenty feet away from the life raft] and the life raft had already been picked up when I boarded the boat. During a short period, I saw the aircraft, it appeared to be in normal level flight.” He remained at the scene after notifying the coroner, supervising the dragging operations.

Mrs. Earl Wren, housewife, testified she saw an airplane hit the high-tension wires which crossed the Fraser River opposite their farm. “There seemed to be an explosion, and the aircraft, after coming over to the right, swung left and I saw it hit the river. The aircraft wobbled badly after it hit the wires.”

Medical Officer Victor Roland testified that when he arrived at the scene of the crash, “there was several small fishing boats on the scene and on one of these was a body identified by F/L Wade as that of F/S Casselman. Identification was confirmed by identification disks around the neck of the body.” He continued to explain how Casselman’s body was moved to a funeral home for an autopsy. The injuries were massive and fatal, including burns and lacerations. “There was a possibility this airman was electrocuted. Death was instantaneous.”

Corporal Wilfred H. McLeay, an Air Engine Mechanic, like F/S Casselman, was called to testify. “At approximately 1000 hours, P/O Evernden came in and asked for an aircraft to do a two-hour flight. I told him that Aircraft 9072 was serviceable but also gave him a list of other serviceable aircraft. Flight Sgt. Casselman asked him where he was going and he replied he was just going up on a familiarization flight to nearby points. F/S Casselman asked who was going with him and he replied, ‘No one, would you like to come along?’ F/S Casselman said, ‘Sure I will be your Navigator.’ Cpl Irving spoke up and asked if he could go, and P/O Evernden said, ‘Certainly.’ He could act as wireless operator. Then he asked Cpl Irving to go over and get a wireless man to set the radio under remote control, which he did. After it was under remote control, he came in and in the meantime Cpl. Sentell had come in from Armament Section. He asked Cpl. Irving where he was going and he told him he was going up with P/O Evernden. Sentell asked P/O Evernden if there was room to go along. He said there was, ‘If you want to ride in the back’, so on getting their parachutes, they entered the aircraft. At approximately 1030 hours, I was standing outside No. 8 Squadron’s Flying Flights Office when P/O Evernden approached and got into Bolingbroke 9072. He was followed by F/S Casselman, who also climbed into the front hatch. Cpl Irving and Cpl Sentell entered the rear hatch of the aircraft. After the engine had been ground tested, the aircraft with these occupants took off.”He could not say if P/O Evernden’s crew was available, adding he did not see any of that crew nearby.

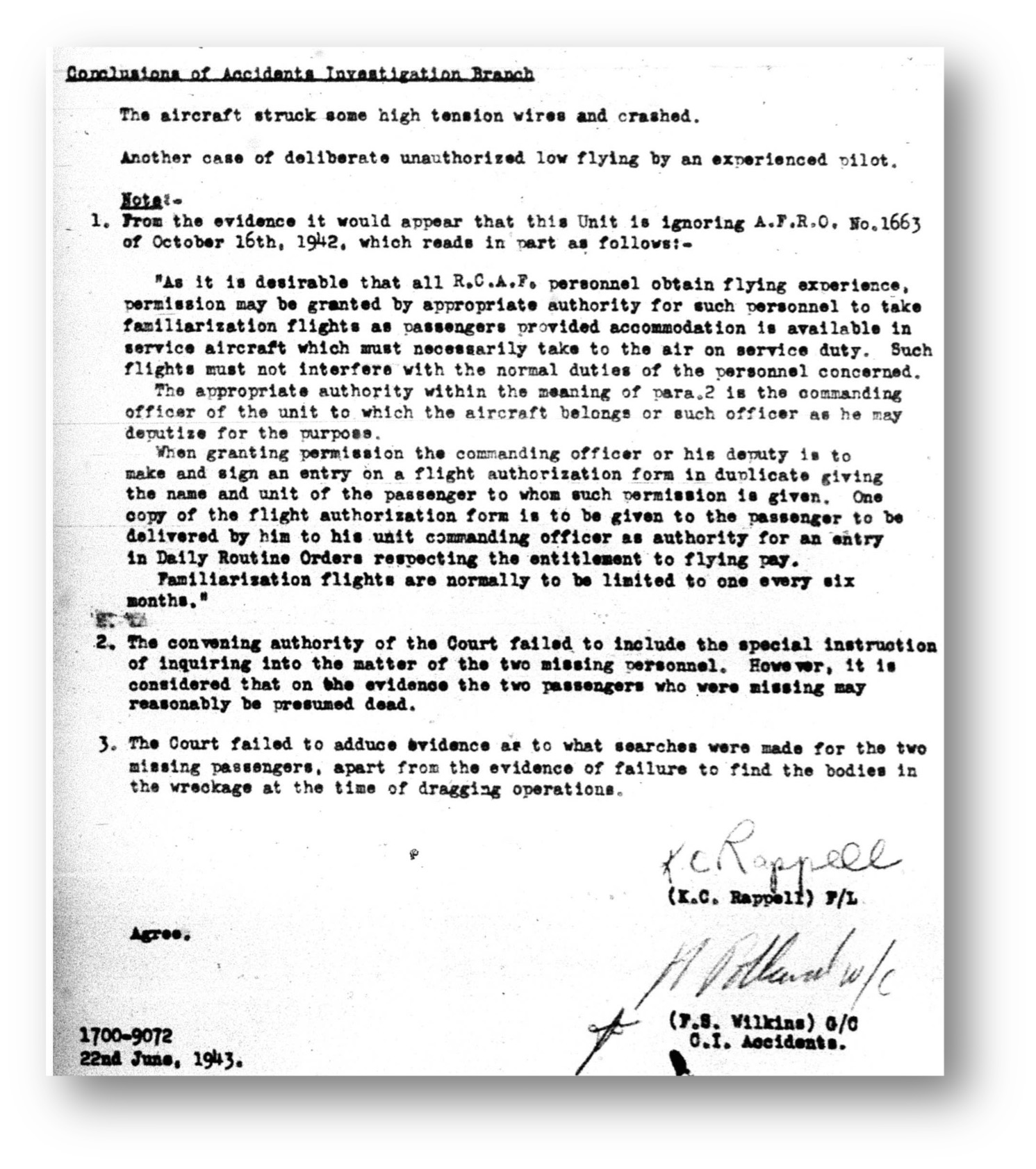

F/L John E. Palmer, Engineering Officer was in charge of the salvage. After the dragging operations were completed, they found the airframe of Bolingbroke 9072. Inside they found the body of P/O Evernden, strapped to his seat, identified by his identity disk. “There were no further bodies found,” he said.

The Court of Inquiry stated, “Another case of deliberate and unauthorized low-flying by an experienced pilot.” They said the evidence pointed to “this Unit is ignoring AFRO Number 1663 of October 16, 1942.” Familiarization flights, too, were normally limited to one every six months.

It was also noted that no authority was given for the ground crew to be aboard Bolingbroke 9072, as the inquiry showed the Flight Commander had no knowledge that they were going to be making the trip, as their names were not on the form. Disciplinary action had been considered for the Officer who authorized the ill-fated flight.

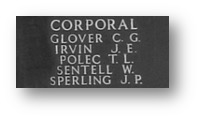

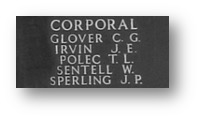

The names of Walter Sentell and James Irving appear on the Ottawa Memorial, Irving’s name missing the ‘G.’ Casselman was buried in Morrisburg (Fairview) Cemetery, Ontario. A stained-glass window at the Lakeshore Drive United Church in Morrisburg also has Casselman’s name on it. Evernden is buried in his family’s plot in Bentley, Alberta.

The full story, along with the profiles of Casselman and Evernden, plus the court of inquiry can be found in Quietus: Last Flight by Anne Gafiuk, now out of print. The book is available through the Calgary Public Library. Copies are also available at the Bomber Command Museum.

LINKS: