February 5, 1920 - April 22, 1943

Thomas James Ritchie was the only child of Thomas Thomson Ritchie, sales manager Tweed Steel Works, and his wife, Elizabeth Mary (nee Galloway) of 106 Follis Avenue, Toronto, Ontario. The family was Presbyterian.

Fishing, photography, baseball, skating and typing were activities that Thomas enjoyed. His academic record included five first class honours and two seconds, and a credit plus one year commercial class.

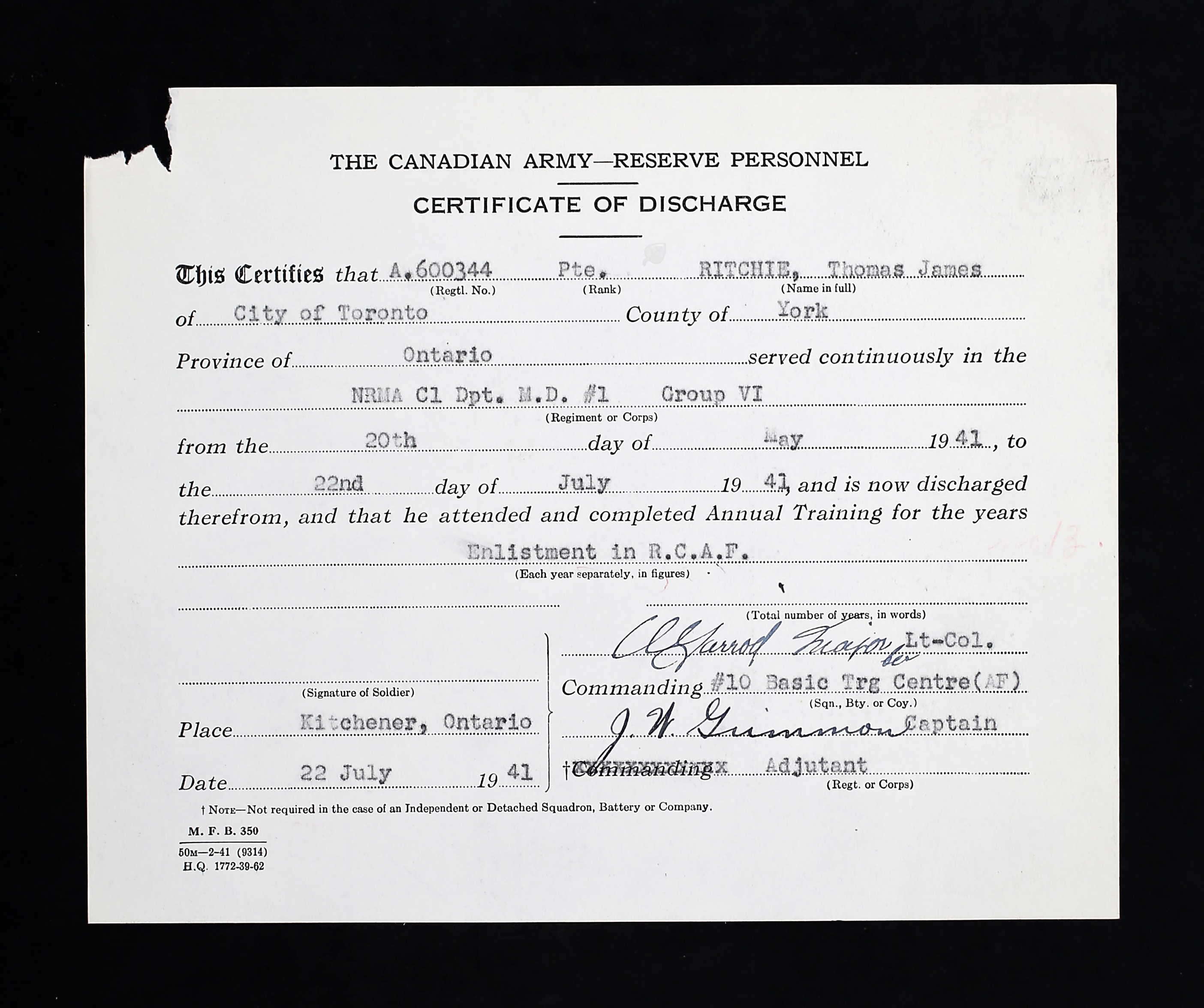

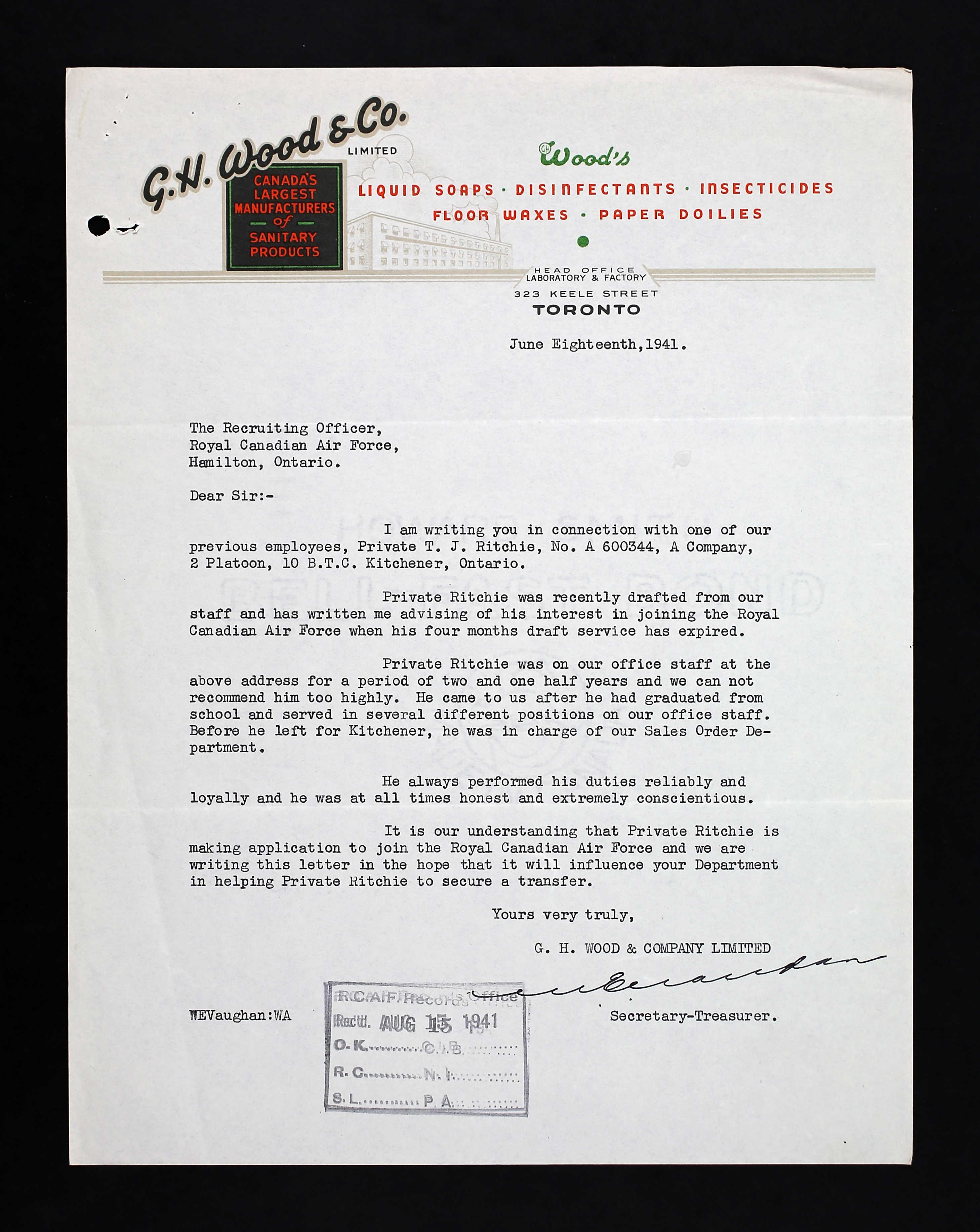

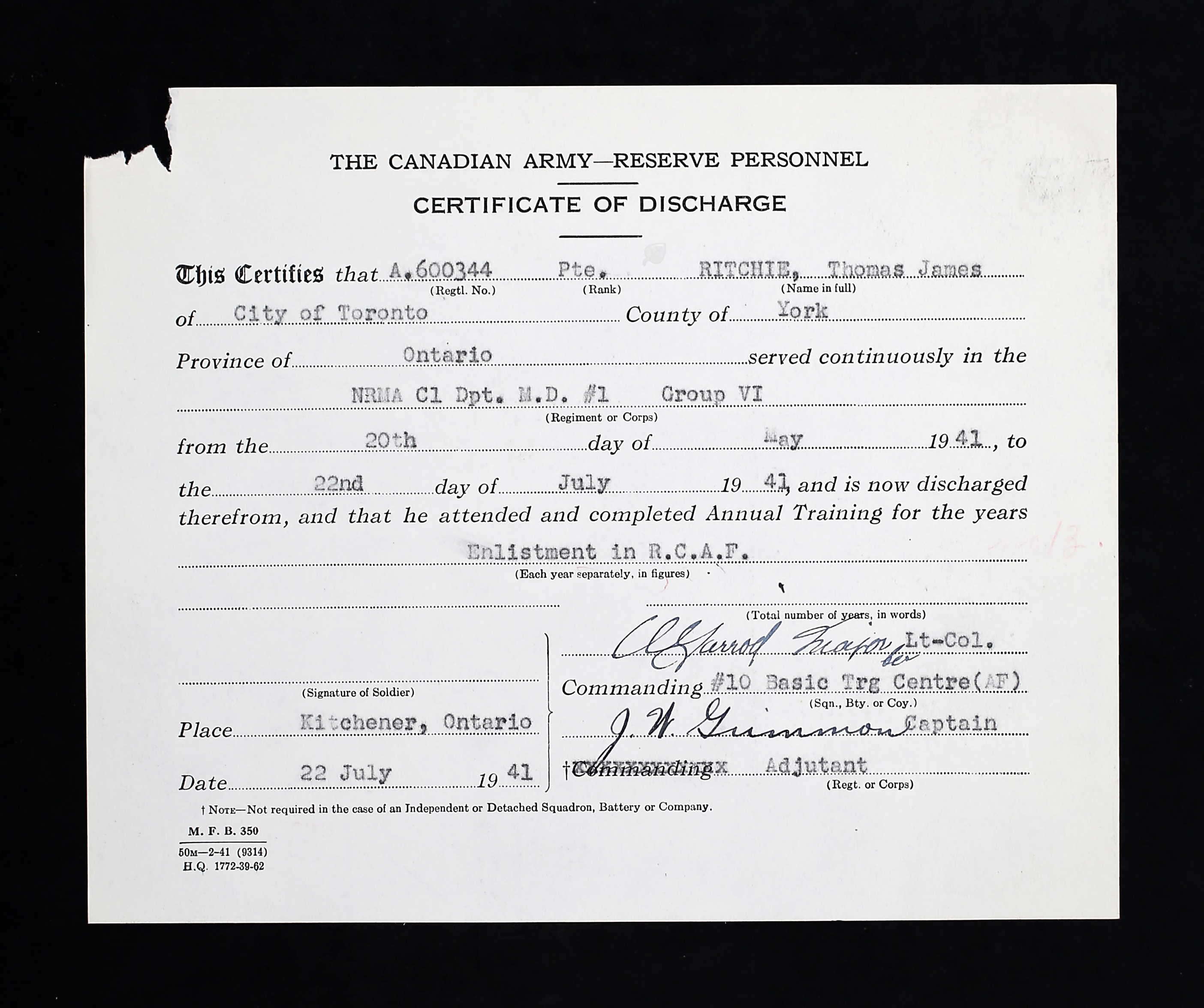

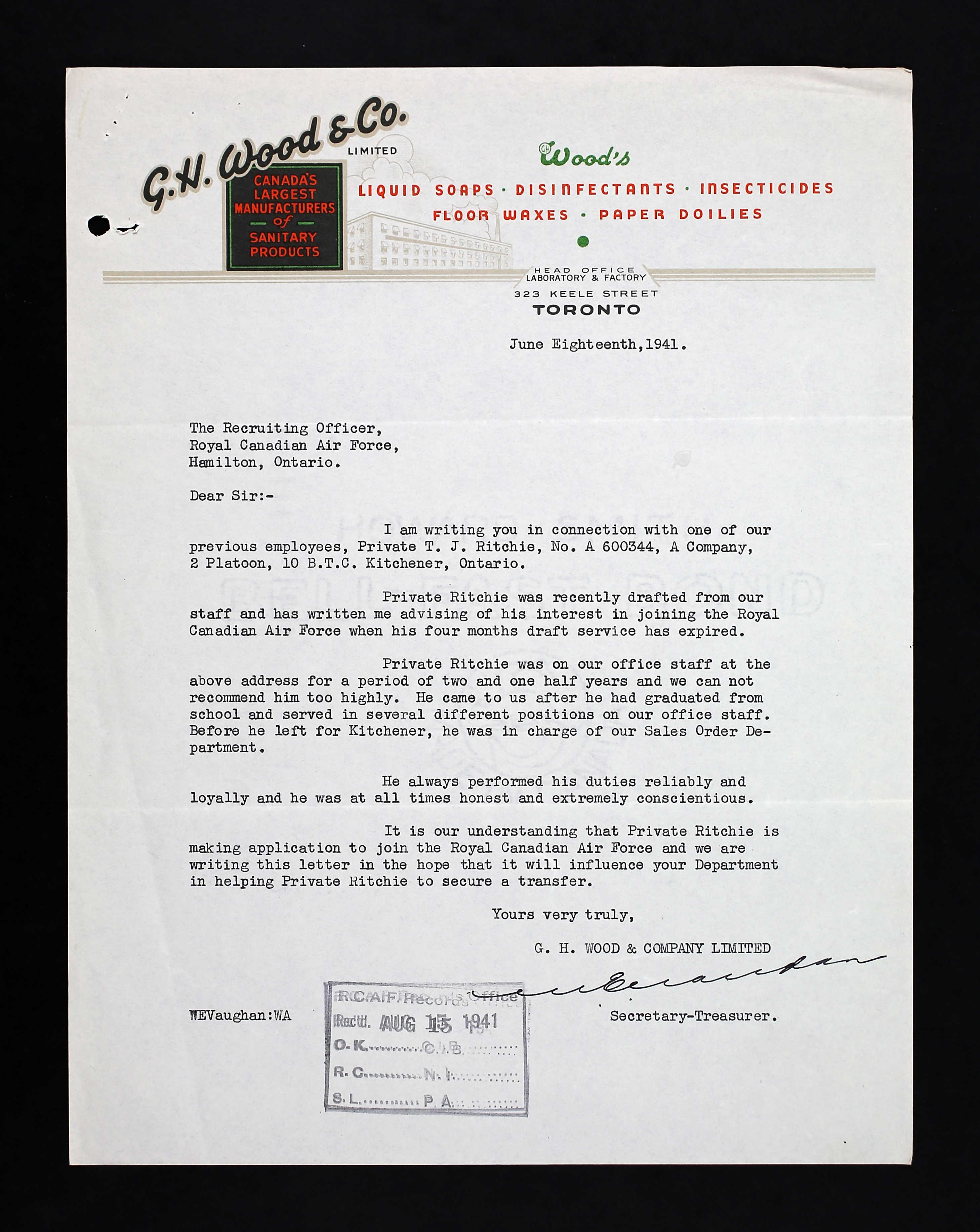

Tom enlisted with the Canadian Army on May 20, 1941, but was discharged on July 22, 1941 so he could join the RCAF to become a pilot in Hamilton, Ontario. He was attached to A Compay, 2 Platoon, 10 BTC, Kitchener, Ontario. When he enlisted with the Canadian Army, he had a preference to join the Navy. He could drive a car, but had no cooking experience, nor could repair a motor. He was in the camp hospital from June 18 to 24, 1941, then transferred to the Toronto Military hospital on June 29 until July 2, 1941. While with the army, he earned $57.60.

Tom stood 5’10” tall, weighed 133 pounds, had brown hair and brown eyes, with a medium complexion. He could read and write in French, but English was his other tongue. He had been an assistant to the sales manager with G. H. Wood Co. Ltd. prior to enlisting with the Canadian Army. He was also in charge of the Sales Order Department at G. H. Wood & Co.

Starting his journey through the BCATP, he found himself at St. Hubert, Quebec at No. 4 Manning Dept from July 24 until August 8, 1941. He was then sent to No. 5 ITS, Belleville, Ontario, on August 9, 1941. He was rejected for aircrew on account of his blood pressure and weight.

On May 16/17, 1942, he was at the American Repatriation Board, Belleville, Ontario on temporary duty and was struck off strength at No. 5 ITS. He had been doing general duties, then clerking duties. He requested to remustered March 30, 1942. He was smoking two pipes daily and drinking a pint of beer a week. His physique was seen as wiry and his mentality: alert. He had two small scars dorsum right thumb and numerous acne scars on his back. “Physically fit, good tone. Performs tests well. Tries hard. Enthusiastic. Prefers fighter pilot. Average intelligence. Good motives. Stable. Grade 7 pilot. Grade 6 Observer.” F/L J. A. D. Marquis. Tom’s application was being considered by the end of June 1942.

“An airman with a year’s service behind him. Is of good appearance, bright and self-confident. Does not co-operate in the flight as well as he might.” No. 5 ITS.

Tom was admitted to the station hospital July 24, 1942.

On September 12 until October 13, 1942, Thomas was sent to No. 20 EFTS, Oshawa, Ontario, but his training was discontinued. He was 36th out of 146 in his class with an 80% in Ground School. “This pupil’s coordination on test was quite poor, judgement weak. On attempts at landings, he was unusually tense on the controls and could not overcome this fault. He seemed to begin leveling off at about the right place but tended to fly into the ground or balloon dangerously without correction. Recommended for Air Bomber.”

Tom then was sent to Composite Training School (KTS) in Trenton October 13, 1942, until a space opened up for him. He traveled to No. 8 B&G School, Lethbridge, Alberta starting his course on November 8, 1942, until February 6, 1943, then to No. 2 AOS, Edmonton, Alberta until April 2, 1943. He earned his Air Bomber’s Badge on March 19, 1943.

By April 4, 1943, Tom had traveled back across the country and arrived at Y Depot, Halifax, awaiting transport overseas. Here he filled out a form confirming his parents’ names and address, noting he had no insurance.

Sometime later, he, with 36 other RCAF airmen, boarded the Amerika. On April 22, while on its way from Halifax, Nova Scotia to Liverpool, it was torpedoed as the ship was heading to Britain. It was a straggler in convoy HX-234. Thirty-seven men, all officers in the RCAF, were presumed missing as a result of enemy action at sea including Thomas. Their ship was sunk by U-306, south of Cape Farewell, off Greenland.

Forty-two crew members and seven gunners were also amongst those who were lost. The master, Christian Nielsen, 29 crewmembers, eight gunners, and sixteen passengers (RCAF airmen) were picked up by the HMS Asphodel, and landed at Greenock. General cargo, including metal, flour, meat and 200 bags of mail were also lost.

Mr. Ritchie received a letter dated June 25, 1943 from F/L W. R. Gunn, RCAF Casualties Officer for Chief of the Air Staff. "Since my letter of May 6th, no additional news has been received. Attached is a list of the names and next-of-kin of sixteen Royal Canadian Air Force officers who embarked on the same ship as your son and following enemy action at sea were safely landed in the United Kingdom. The following official statement was made in the House of Commons....’I have been in receipt of communications from a number of members of this house and from people outside with reference to rumours regarding the recent loss of a number of members of the RCAF by the sinking of a ship in the north Atlantic and I desire to make the following statement on the facts. The vessel in question was a ship of British registry of 8,862 tons, designed for peace-time carriage of both passengers and freight, and having a speed of fifteen knots. She carried a crew of 86 and the passenger accommodation consisted of 12 two-berth rooms with bath and 29 other berths, providing cabin accommodations for 53 passengers. She was fitted with lifeboat capacity for 231 and travelled in naval convoy. Under the recently revised regulations agreed to by the United States authorities, the joint United Kingdom and United States shipping board, the Admiralty, the Air Ministry and the Canadian authorities, a vessel of this description travelling in convoy is permitted to embark as crew and passengers a maximum of 75% of the lifeboat capacity. The lifeboat capacity as stated above was 231, 75% of which is 173. Personnel on board consisted of the crew of 86, and RCAF personnel numbering 53, a total of 139, well within the prescribed limits. Because of the superior type of available passenger accommodation, the speed of the ship and the provision of naval convoy, the offer of the entire available space to the RCAF was immediately accepted. Rumours to the effect that this was a slow freighter not suitable for passenger accommodation are, of course, not in accord with the facts. Every precaution was taken to safeguard the lives of these gallant young men. It should be pointed out that on account of the serious shipping shortage every available berth on such ships must be used, and had the space not been taken up by the RCAF officers of the other arms of the services would have been placed on Board. It should also be stated again that the submarine is still the enemy’s most powerful weapon and that the Battle of the Atlantic is not yet won. Any ocean trip today in any part of the world is fraught with danger and I think I may safely say that our record in transporting our soldiers and airmen to the United Kingdom is one of while we may all be proud. No one deplores more than I do the loss of 37 of the finest of our young men who gave their lives for their country as surely as if they had done so in actual combat with the enemy, and I extend my deepest sympathy to their loved ones in their bereavement.’ If further information becomes available, you are to be reassured it will be communicated to you at once. May I again extend to you my sincere sympathy in this time of great anxiety."

Attached to the letter was a list of the names and next-of-kin of sixteen RCAF officers who embarked on the same ship as Tom survived and were safely landed in the UK.

In early January 1944, Tom’s mother received another letter from S/L W. R. Gunn that Tom would now be presumed dead for official purposes.

Mrs. Ritchie was the sole beneficiary of Tom’s estate. He had $110 worth of War Savings Certificates and $200 worth of Victory Loan Bonds, but no life insurance. He had $157 in savings with the Canadian Bank of Commerce. Mr. Ritchie wrote, “He said he had made a will in favour of his mother. Possibly you have the will in some branch of the RCAF. He had a post office savings account but whether this was closed before he left, we do not know as our son took all his records with him when he left.”

In October 1955, a letter addressed to Mr. Ritchie arrived from W/C W. R. Gunn informing her that Thomas’s name would appear on the Ottawa Memorial, as Tom had no known grave, expressing sympathy on the loss of her gallant son.