July 5, 1921 - April 22, 1943

Richard Scott McCloskey, known as Scottie, was the son of James David McCloskey and Catherine Louise (nee Scott) McCloskey of 1 Elm Street, Ottawa, Ontario. He had three older brothers, Harold, Elmer, and William, who was a F/S in the RCAF at Souris, Manitoba. Scottie also had two sisters: Dorothy and Rita. The family was Roman Catholic.

He enjoyed hockey, football, softball and swimming moderately. He had been a passenger in a plane for 30 minutes, but had no other prior flying experience.

Scottie worked as an office boy/clerk/civil servant in the Supplies and Distribution Branch of the Department of Labour after his schooling at St. Malachy’s School and St. Patrick’s College in Ottawa. Prior he had been a messenger for the CPR. He was fluent in English with a “slight knowledge of French.”

Scottie applied to the RCAF on May 29, 1940, in Ottawa, wishing to be an Air Gunner. His previous military experience was being in Sea Cadets for approximately four months. “Good background, clean character, trustworthy in every respect. Good material. Should absorb training readily. Immature, but keen and alert.”

He was left-handed. He had a scar on his left kneecap. His physique was considered sedentary. He stood 5’9” tall, weighing 127 pounds. He had brown hair and brown eyes, with a medium complexion. On July 9, 1940, Major H. A. Peacock RCAMC noted that Scottie was underweight, slow, had poor self-balance and was a doubtful candidate.

Despite that assessment by Major Peacock, Scottie was accepted into the RCAF and began his training through the RCAF at No. 1 Initial Training School, Toronto, Course 3 from June 24 to July 20, 1940. He earned an 83% and was 100 out of 244 in his class. “Good at maths.” He was selected as a suitable pilot material.

From July 22 to September 14, 1940, Scottie attended No. 2 Elementary Flying Training School, Fort William, Ontario, Course 3. He earned 72.9% and was assessed as average as a pilot. “Has shown favourable progress. Is rough on controls. Does not synchronize movements. Needs further practice on steep turns (slips) (too steep).” In his ground training: “71.2%. 17th out of 20 in class. Appearance good. Conduct good. Average ability. Energetic and high spirited.”

From September 15, to November 17, 1940, Scottie was at No. 4 Service Flying Training School, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. “Uses too much throttle on landings. Consequently, uses all of runway. Steep turns are poor. Does good aerobatics.” In ground training: “Recommended as suitable for commission. Keen,” Chief Ground Instructor. It was noted he was unsuitable for commission by the Officer Commanding. “Discipline satisfactory. Inclined to be lazy.”

Scottie was awarded his Pilot’s Flying Badge on November 18, 1940.

He was sent to No. 9 SFTS, Summerside, Prince Edward Island, March 23 until July 30, 1941. From there, he was sent to Central Flying School, Trenton, April 15, 1942, where he received his commission. He was sent to Rockcliffe, Ottawa to No. 3 FIS, Arnprior, Ontario until March 21, 1943.

Scottie married Dorothea Paige (nee?) on March 22, 1943, at St. Patrick’s Church, Ottawa. She lived at Apt. 8, 107 Preston Street in Ottawa.

Scottie held a $5000 life insurance policy containing a war clause limiting payment, payable to his estate in the case of an untimely death. He also had one $100 bond purchased through the RCAF.

By April 13, 1943, Scottie was at Y Depot, Halifax, awaiting transport overseas, in hospital that day. Some time later, he, with 36 other RCAF airmen, boarded the Amerika. On April 22, 1943, near Greenland, a German U-boat torpedoed the Amerika. Scottie was not one of the survivors.

Dorothea received a letter dated June 25, 1943 from F/L W. R. Gunn, RCAF Casualties Officer for Chief of the Air Staff. "Since my letter of May 6th, no additional news has been received. Attached is a list of the names and next-of-kin of sixteen Royal Canadian Air Force officers who embarked on the same ship as your son and following enemy action at sea were safely landed in the United Kingdom. The following official statement was made in the House of Commons....’I have been in receipt of communications from a number of members of this house and from people outside with reference to rumours regarding the recent loss of a number of members of the RCAF by the sinking of a ship in the north Atlantic and I desire to make the following statement on the facts. The vessel in question was a ship of British registry of 8,862 tons, designed for peace-time carriage of both passengers and freight, and having a speed of fifteen knots. She carried a crew of 86 and the passenger accommodation consisted of 12 two-berth rooms with bath and 29 other berths, providing cabin accommodations for 53 passengers. She was fitted with lifeboat capacity for 231 and travelled in naval convoy. Under the recently revised regulations agreed to by the United States authorities, the joint United Kingdom and United States shipping board, the Admiralty, the Air Ministry and the Canadian authorities, a vessel of this description travelling in convoy is permitted to embark as crew and passengers a maximum of 75% of the lifeboat capacity. The lifeboat capacity as stated above was 231, 75% of which is 173. Personnel on board consisted of the crew of 86, and RCAF personnel numbering 53, a total of 139, well within the prescribed limits. Because of the superior type of available passenger accommodation, the speed of the ship and the provision of naval convoy, the offer of the entire available space to the RCAF was immediately accepted. Rumours to the effect that this was a slow freighter not suitable for passenger accommodation are, of course, not in accord with the facts. Every precaution was taken to safeguard the lives of these gallant young men. It should be pointed out that on account of the serious shipping shortage every available berth on such ships must be used, and had the space not been taken up by the RCAF officers of the other arms of the services would have been placed on Board. It should also be stated again that the submarine is still the enemy’s most powerful weapon and that the Battle of the Atlantic is not yet won. Any ocean trip today in any part of the world is fraught with danger and I think I may safely say that our record in transporting our soldiers and airmen to the United Kingdom is one of while we may all be proud. No one deplores more than I do the loss of 37 of the finest of our young men who gave their lives for their country as surely as if they had done so in actual combat with the enemy, and I extend my deepest sympathy to their loved ones in their bereavement.’ If further information becomes available, you are to be reassured it will be communicated to you at once. May I again extend to you my sincere sympathy in this time of great anxiety."

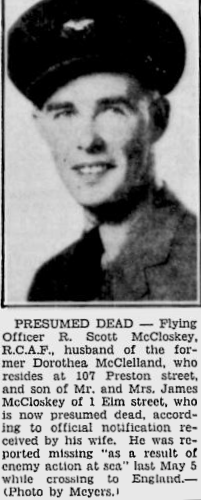

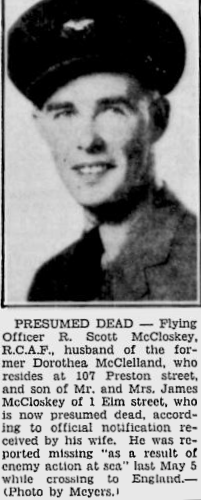

In early January 1944, Dorothea received another letter from S/L W. R. Gunn that Scottie would now be presumed dead for official purposes.

By 1950, Dorothea had remarried and was Mrs. Jenkins. Scottie’s medals were undelivered and were returned to stock.

In October 1955, another letter from W/C W. R. Gunn was mailed to Dorothea, but a note on the letter stated that the letter was returned and the RCAF was to send verification to Scottie’s mother, informing her that Scottie’s name would appear on the Ottawa Memorial.