August 9, 1920 - January 5, 1943

Paul Cleveland Bernstein, born in Miami, Florida, was the only child of Ina Cleveland (nee Knapp) Doolittle (1884-1951). Her first husband, Harry Bernstein, Paul’s father, passed away of heart disease. He was a salesman. She married George Doolittle (1881-1956). Paul was Jewish.

Paul was a student. He had part time jobs as a gas attendant, doing general laundry, truck driving, and as a truck helper. He enjoyed two glasses of wine per week at mealtime and smoked cigarettes. He stood 5’9” tall and weighed 124 pounds. He had brown eyes and brown hair. His physique was noted as sedentary and he had a standard mentality. “Slight trace of albumen. Poor eye convergence tests.” Some athlete’s foot was treated and cured. “Considerable kyphosis” (curvature of the spine).

He liked football, baseball, basketball, swimming, ice hockey, tennis, golf, and bowling.

On his interview report: “Not impressive but seems sincere and is persistent. Can be smartened up with Drill and Discipline.” He was rated as below average.

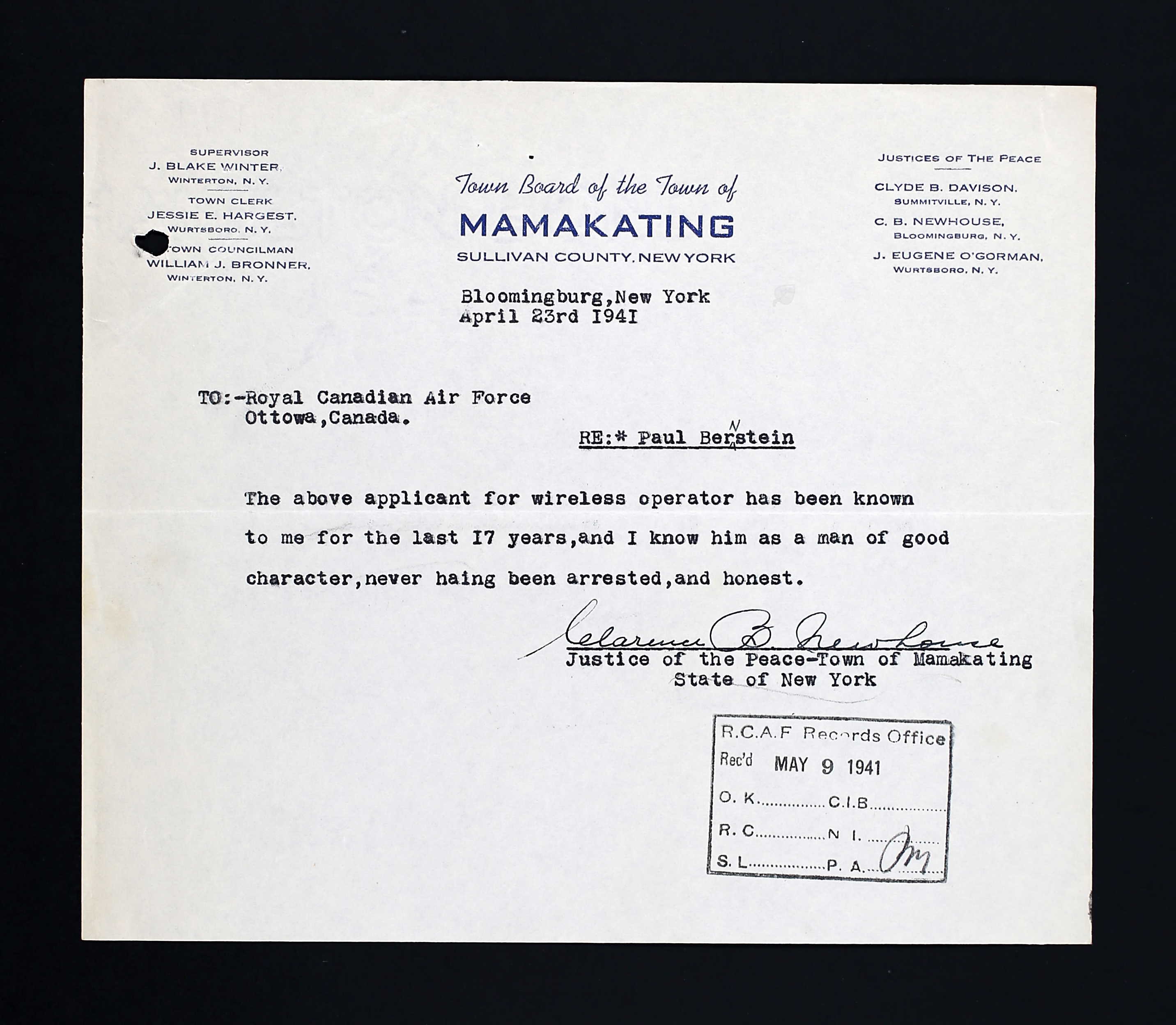

On his attestation papers, his address was Middletown, New York. While he waited for acceptance into the RCAF, he resided at the YMCA, Ottawa, Ontario in April 1941.

Paul took out five life insurance policies totalling $1533, payable to his mother.

Paul’s journey through the BCATP started at No. 1 Manning Depot, Toronto, Ontario on May 7, 1941. He was then sent to No. 1 Wireless School, Montreal, Quebec June 23, 1941 until May 23, 1942. He was 24th out of 97 in his class, earning 79.5%.

He was then sent to No. 1 B&G School, Jarvis, Ontario, May 24 until July 11, 1942. He tied for 10th place out of 30 students in air training/gunnery. “Good average student. Made good class leader.” Overall, he was 11th. “Keen with good sense of responsibility. Good mixer. 76.7%”

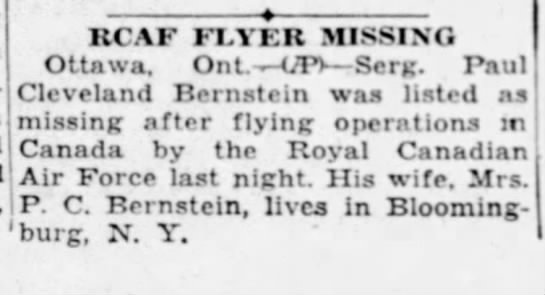

Paul married Marjorie Newhouse, residing in both Wawayanda and Bloomingburg, NY on June 25, 1942 while he was at No. 1 B&G School, Jarvis, Ontario. Marjorie worked at the Agricultural Conservation Association in Middletown, NY prior to her marriage.

He was then sent to No. 1 GRS, Summerside, PEI July 12, 1942.

He forfeited many days’ pay as he was AWL. At No. 1 Wireless School in Montreal, he was absent from July 8 to August 22, 1941 (76 days). He forfeited 77 days’ pay. He again was AWL at No. 1 WS from February 9 to February 19, 1942. He was confined to barracks for seven days and forfeited two days’ pay. Paul was in the hospital from November 22-25, 1942 for strep throat.

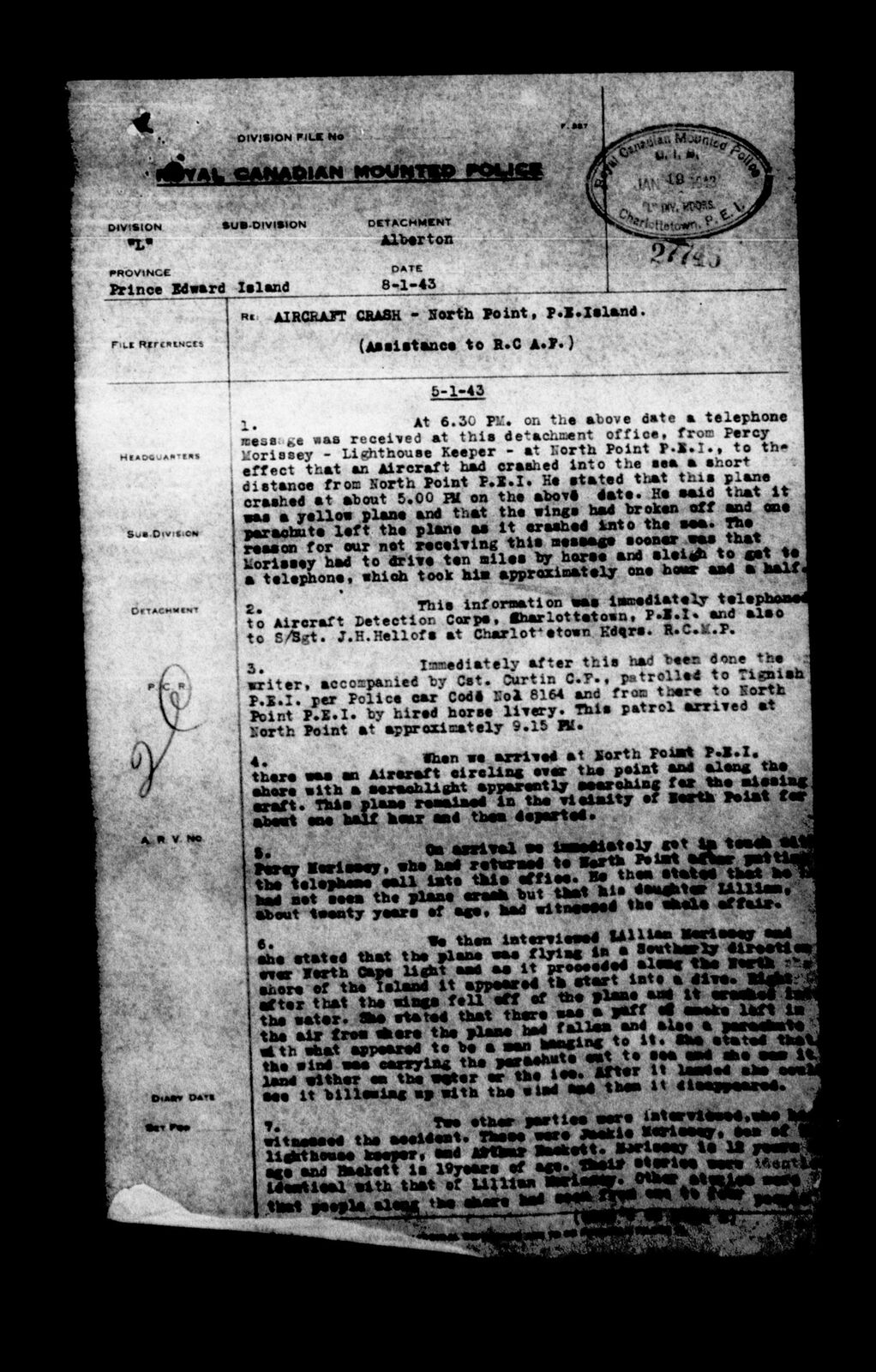

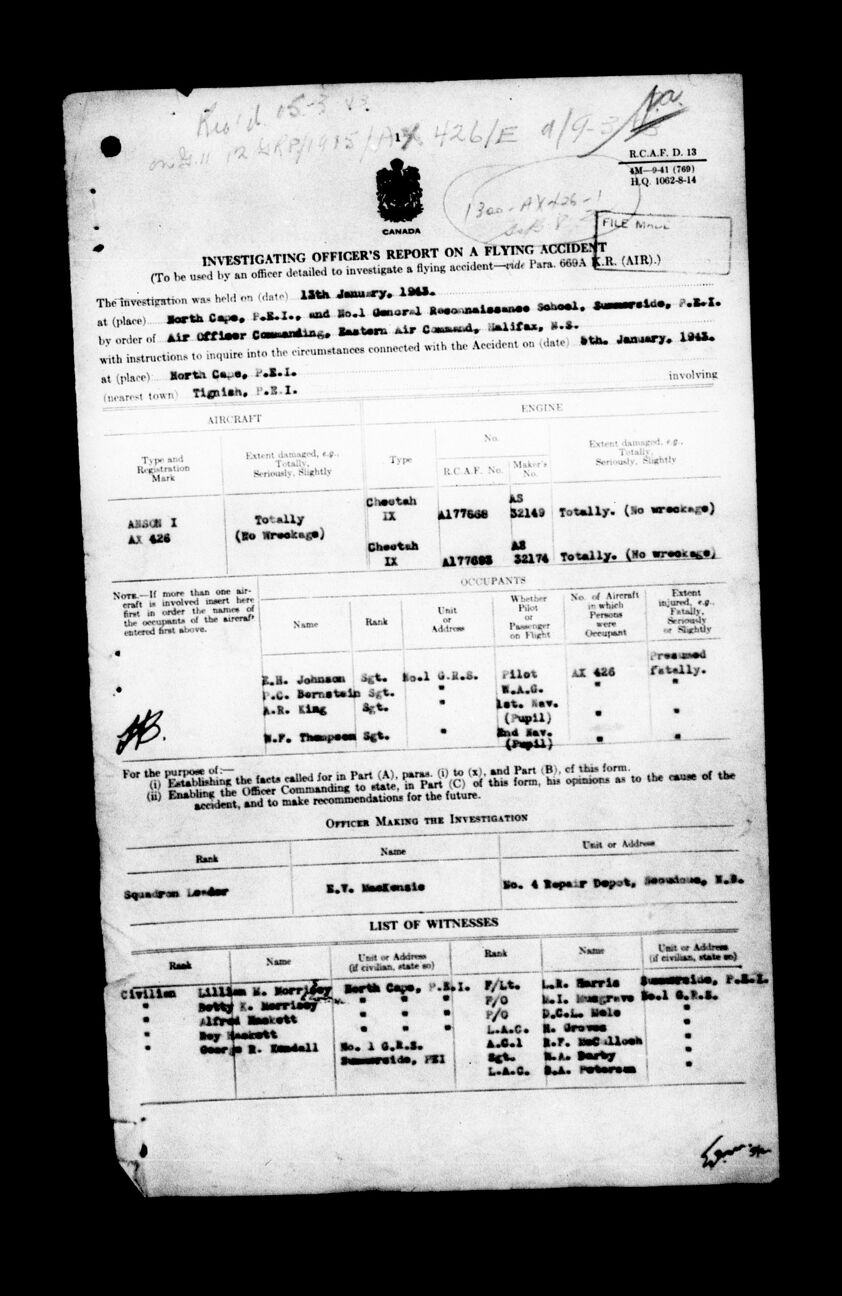

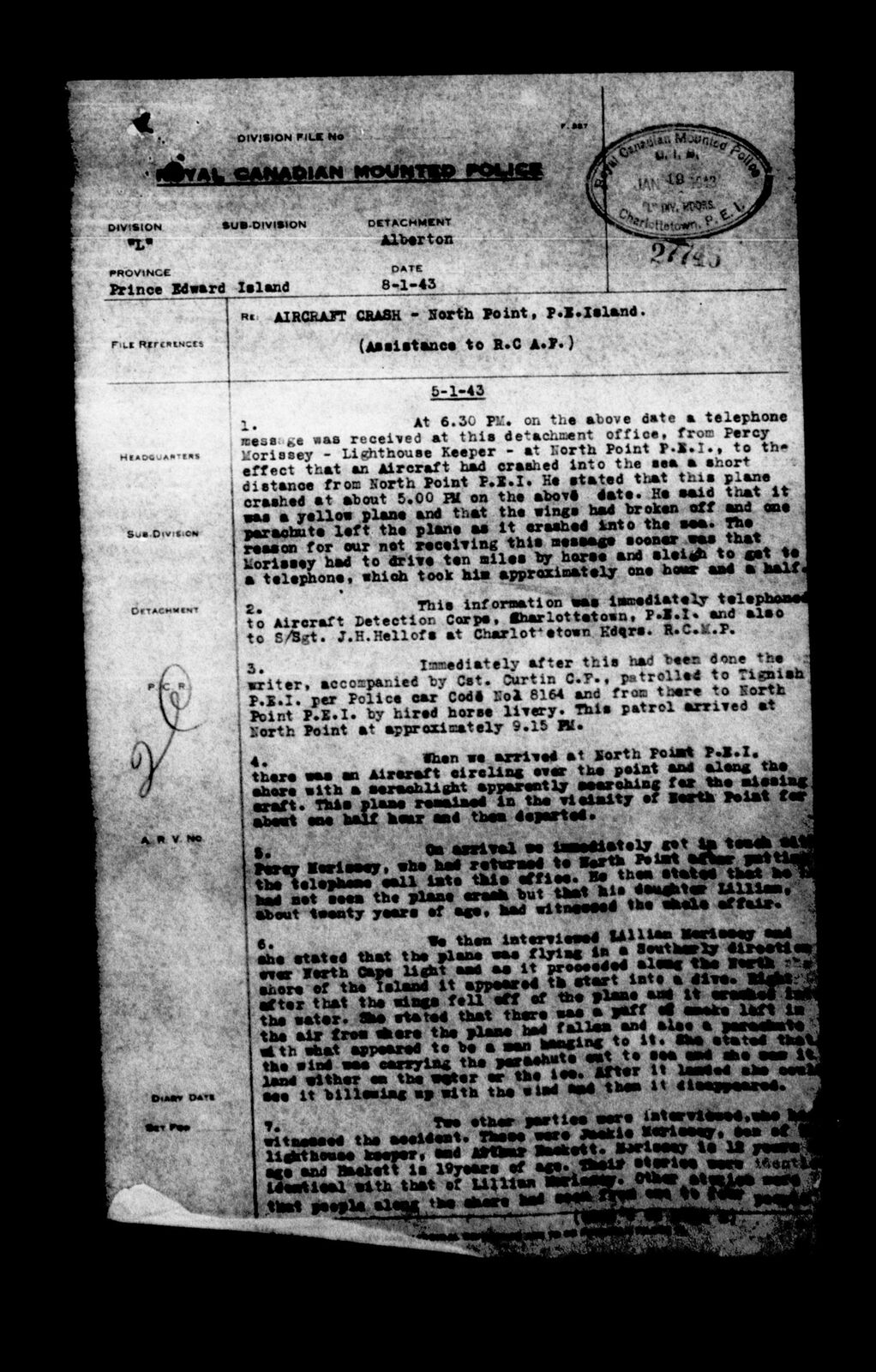

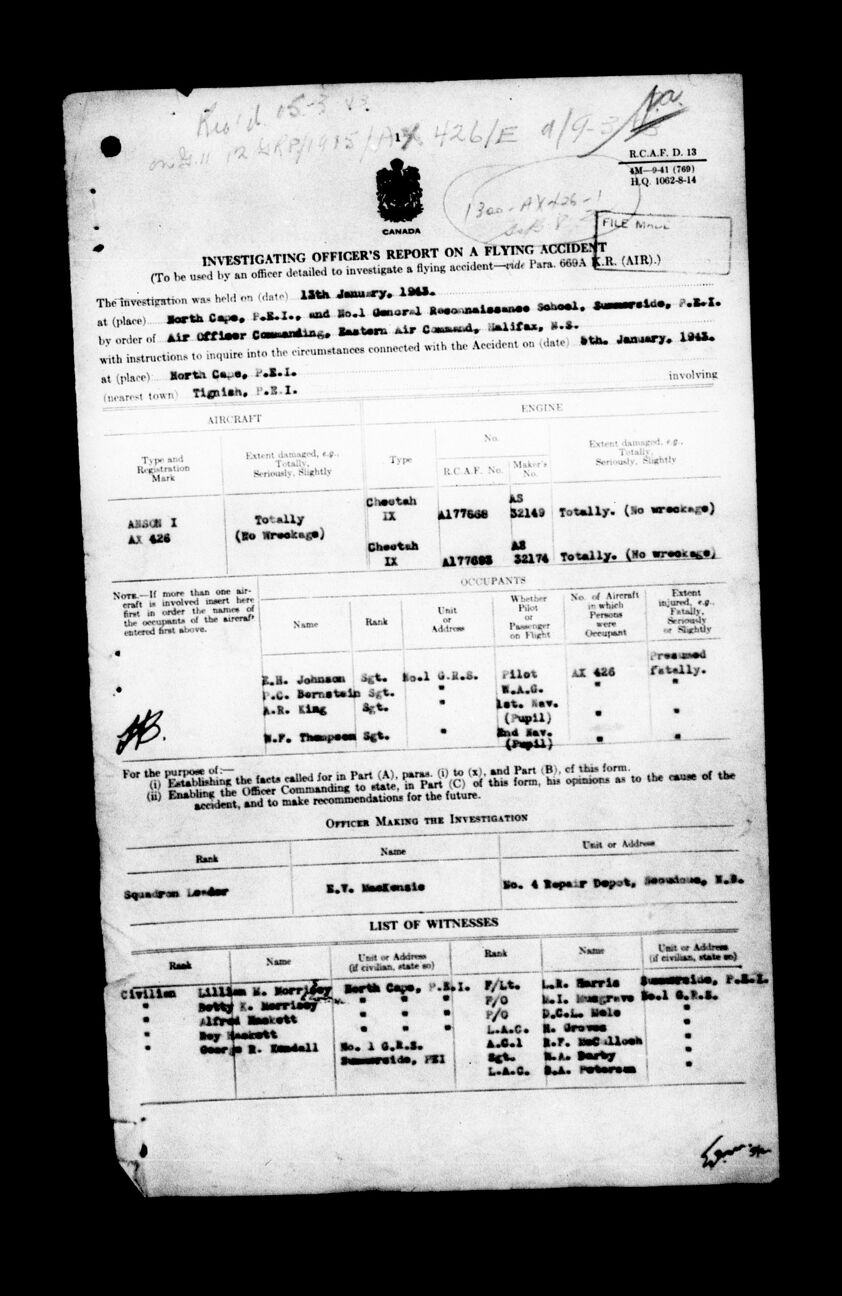

On January 5, 1943, at about 1700 hours, Anson AX426, with No. 1 General Reconnaissance School, Summerside, PEI, disappeared on a routine navigation exercise. Paul was aboard along with Pilot Sgt. Eric Harold Johnson, 657936, RAFVR, First Navigator Sgt. Alexander Russell King, 1345198, RAFVR, and Sgt William Frederick Thompson, 1238664, RAFVR, England. Thompson was a pupil navigator; his body was later recovered and was buried at Sherwood Cemetery, Brackley, Queen's County, PEI.

A Court of Inquiry was struck, from January 13 to 18, 1943. Twelve witnesses were called including civilians and military personnel.

The FIRST WITNESSES Lillian and Betty Morrisey stated that they saw “bits of the aircraft fall away and after a very short upward climb, the aircraft seemed to turn about and it went straight into the water about 400 yards off shore and about three quarters of a mile from the lighthouse. At about that same time, we noticed a parachute drifting with the wind towards the northeast. At the same time, we also noticed a speck of smoke at the spot where the aircraft started falling. When we lost sight of the parachute, it was drifting out over the ice. I notified my father, Perry Morrisey. He then drove to Tignish and notified the Mounted Police by telephone.

The SECOND WITNESS, Alfred Hackett, concurred with the Morrisey sisters, adding that “I noticed a good-sized patch of black smoke. Immediately afterward, I saw the end of the right-hand wing come off together with a fairly large piece from the front end of the airplane. There was also a piece which appeared shiny that came away. During this time, one of the men jumped out of the airplane in a parachute. I saw the parachute open, and he floated down and landed on the ice. The rest of the airplane came down and crashed through the ice at a distance of about ½ mile from shore. I did not see any more of the man after the parachute touched the ice. The parachute was blown around for a little while. Not having a suitable boat, we were not able to go out into the water.”

The THIRD WITNESS, Roy Louis Hackett, agreed with the other witnesses, adding “I saw an aircraft coming over the top of the trees from the north. It didn’t seem to be very high and I thought that it was neither climbing nor diving. When it got about abreast of the house, it seemed to turn to the east and on turning to the east, I felt that it was starting to come down for a little while, then appeared to go upwards. About this time I am positive I saw the largest part of the left wing come off. I also saw several smaller pieces come away from the airplane and then I saw a man jump out in a parachute. I could not tell whether the man landed on the ice or not, but I did see one parachute blowing for some time after it had reached the ice. About the time the wing came off, I heard what I thought was a strange noise of an aircraft and some smoke appeared.”

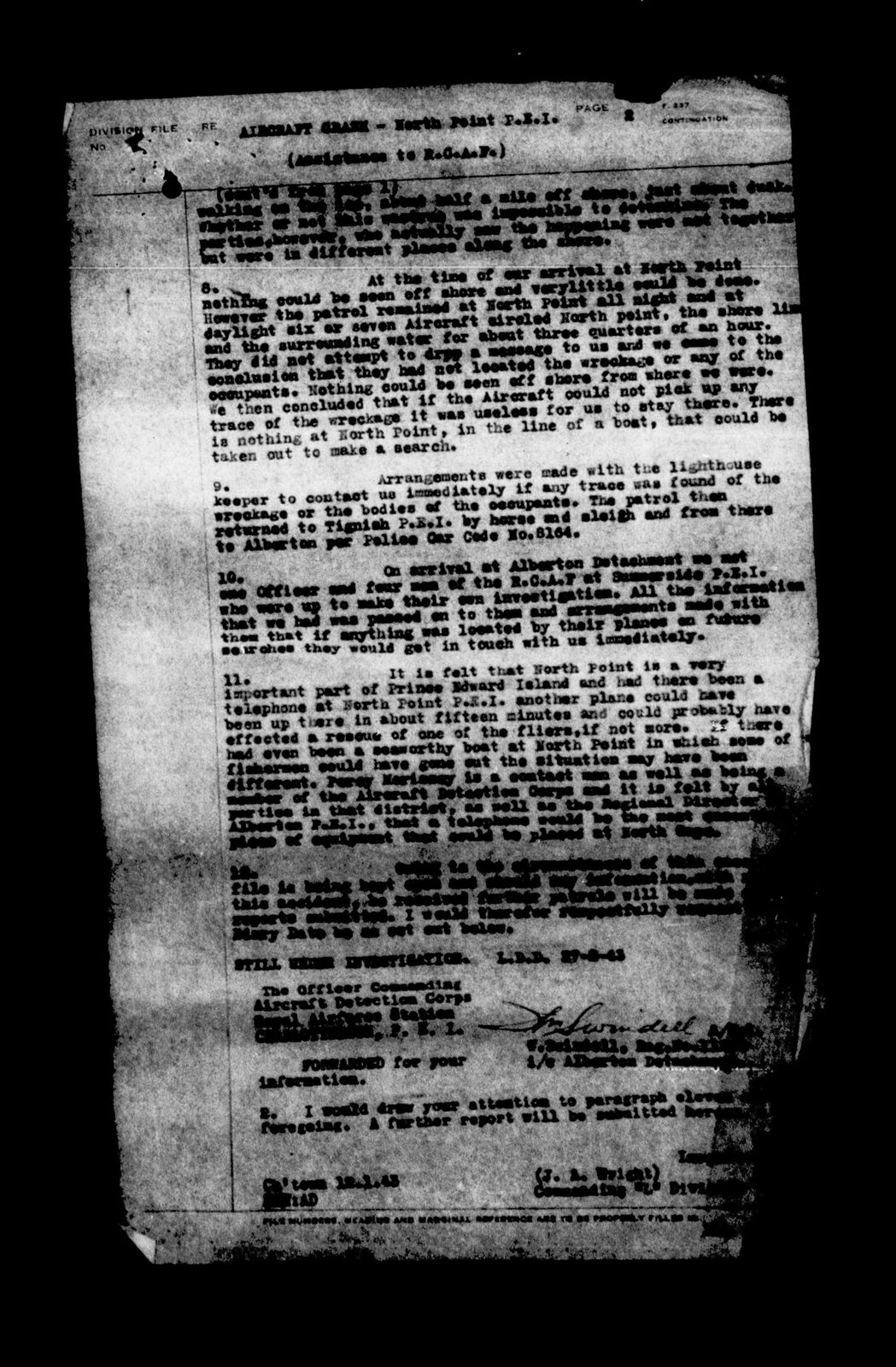

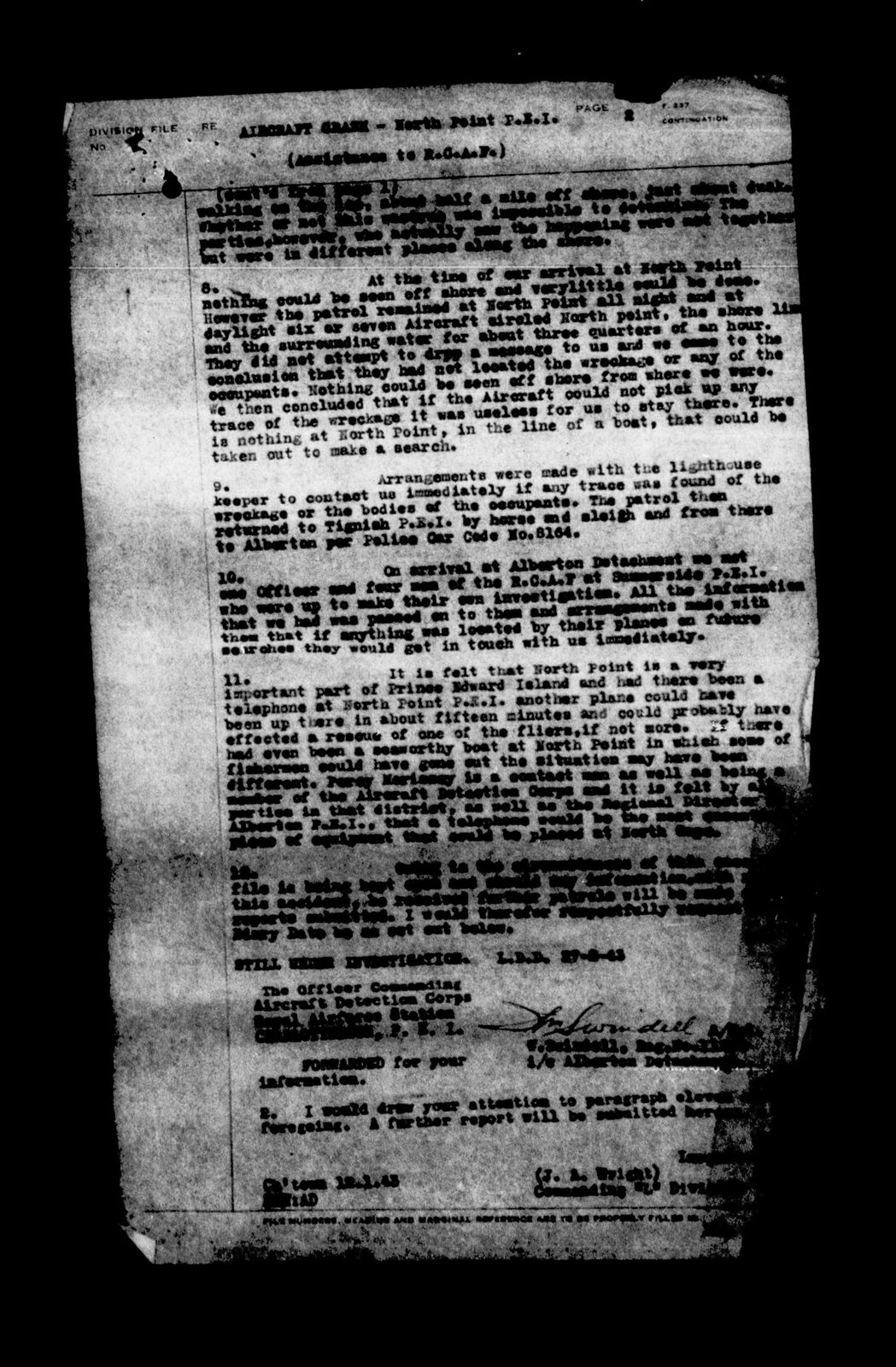

The FOURTH WITNESS, F/L Reginald Leslie Harris (RAF) stated that he was informed that the aircraft was overdue. “I immediately took overdue action as laid down in station standing orders.” He received a call from the RCMP telling him that an aircraft had gone into the sea. “The delay between the accident and the time I received the report was caused by the lighthouse keeper at North Point having to arrange a horse and sleigh transportation and proceed nine miles in order to go to Tignish to telephone, there being no telephone nearer. By this time, it was dark and one aircraft was dispatched complete with flares for search duty. A further search was organized in conjunction with Eastern Air Command controller taking off at dawn the following morning. This search continued during the day but produced no results.

The SIXTH witness, P/O Derek Charles Lovelace Mole was the navigation instructor who had known the two navigators for about six weeks. “As Navigators, they were very good, but I felt that they were both very young and irresponsible. They were very good friends.”

The SEVENTH AND EIGHTH witnesses commented as to the condition of the aircraft, both feeling it was in good flying order.

The TENTH WITNESS, Sgt. William Arthur Darby, RAF, stated that the weather conditions at that time were good for flying, generally. No icing, visibility 15-20 miles with broken clouds about 2000 feet.

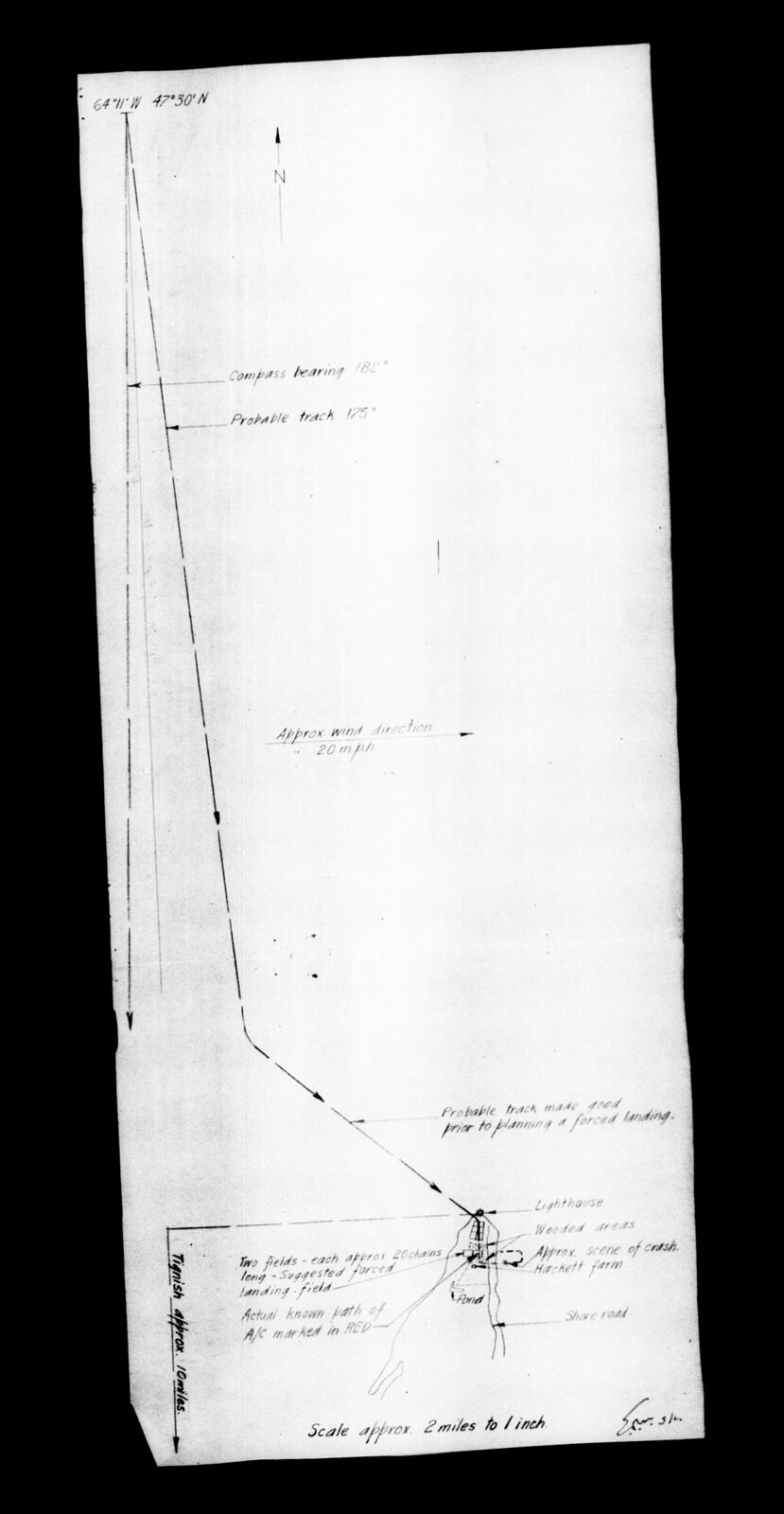

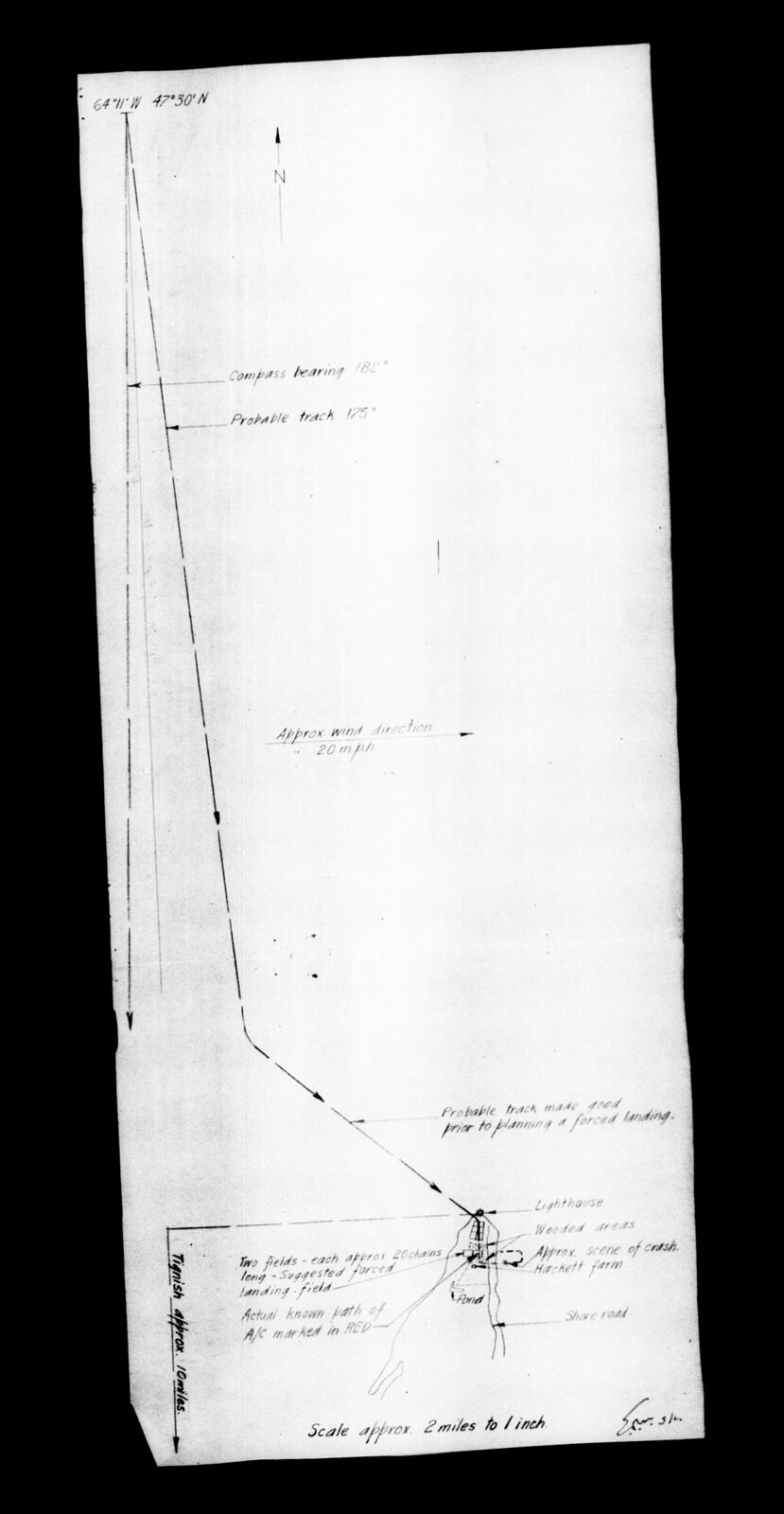

OBJECT OF FLIGHT: Navigational exercise to be carried out under supervision of pilot. PILOT: Sgt Johnson was assessed by his Flight Commander as an able pilot, but somewhat too ‘adventurous.’ During inquiry at Summerside, the Investigative Officer was convinced by the staff that Sgt Johnson had been checked frequently for reckless (or improper) flying although it is agreed that he was a capable pilot. DESCRIPTION OF FLIGHT: Sergeant Johnson was pilot, with Sergeants Thompson, King, and Bernstein as crew, took off on an authorized navigational exercise, R7, at 1520 hours. Sergeant Bernstein was acting as wireless operator, while Sergeant Thompson and King acted as navigators. The duty instructor was notified that the exercise was proceeding in a normal manner, and did not feel anything amiss until he received no message from the aircraft and it became overdue. He therefore informed the Flight Commander. The last position signal was received at 1639 hours, information was later received that the aircraft had crashed at approximately 1700 hours. From the estimated position given at the time of the last signal and assuming that the aircraft was performing in a satisfactory manner, it should have reached the scene of the accident in approximately 15 minutes. The aircraft was seen near, where it crashed, by several witnesses, to have performed a maneuver described as a climb from a low altitude when the port wing came away and the aircraft crashed through the ice approximately 1/2 mile offshore. Two of the eyewitnesses stated they saw a man leave the aircraft and parachute to the ice; except for the parachute blowing on the ice, nothing more was seen and no suitable boat being available, any rescue attempts were frustrated. No trace of the personnel or wreckage has been found. Note it is however the opinion of the investigating officer that if a search were desired, a boat with suitable drag could, without too much difficulty, recover some or all of the wreckage. FINDINGS OF THE INVESTIGATION: Obscure, but it appears the pilot was having difficulty with his aircraft and was preparing to make a forced landing into wind on fields slightly to the north of the Hackett Farm at North Cape, PEI. RECOMMENDATIONS: Lacking actual facts as to the real cause of the accident, no recommendation is extended.

The aircraft’s logbooks were examined by S/L C. H. Cotton. The following structural repairs were made: “As a result of a taxiing accident, No. 4 RD between 17 August 1942 and 17 September 1942 repaired the rear spar, wing tip, and trailing edge of rib 18 of the starboard wings. The aileron and rudder were also replaced as the result of this accident.”

The Senior Medical Officer S/L H.E. Hanna reported that Sgt Johnson’s medical category “has been always fit, all flying duties, A1B, A3B. Medical record of abnormalities: 1937: stomach operation on account of injury received while playing rugger. 1934, right orchidectomy on account of injured right testicle. No other detaisl available. Sgt King: Medical category A1B, A3B. Acute streptococci, November 1942. Recovered. Sgt. Thompson: Medical catetory A1B, A3B. No medical abnormality. Sgt. Bernstein: April 12, 1941, recruit medical examination Station Recruiting Centre. On account of slight Albuminuria (protein in urine, possible diabetes), borderline ocular objective convergence and ocular accommodation. Recheck in May 1941: urine albumen free and ocular objective convergence and accommodation satisfactory. Nov. 1942: acute streptococcal throat. Sick three days.”

ADDITIONAL REPORT: This report is the opinion of the Investigating Officer and may help to throw some light on understanding the accident and may be used as part of the proceedings or not, as may be decided by higher authority. Too much cognizance was not placed on the statements of the Morrissey sisters and it seemed evident on questioning that they were entirely too far away from the scene, and much too unqualified as witnesses to be able to testify with any certain degree of dependability. The Investigating Officer felt that the statements of the witnesses, Mr Alfred Hackett and Mr Roy Hackett, were probably the truest accounts, since the entire accident took place immediately in front of the Hackett farmhouse, outside of which they were standing. It seems that these Hackett boys frequently see and hear Anson aircraft and are fairly familiar with their sight and sound, and while they are not considered by the Investigating Officer to be competent as technical witnesses, it is felt that they were the best witnesses available for the purposes of this investigation. The Hackett boys were questioned separately outside each other's hearing, and were both most emphatic in the fact that the port wing definitely came away from the aircraft. They also stated that the fuselage bobbed up and floated on the surface for a few minutes, they also stated that several bits came away. The mother of the Hackett boys stated that while she did not actually see the aircraft, she did see the parachute descending, likewise a pool of black smoke over the area. Investigating Officer did not feel that her statement would assist in the proceedings. The position of the wreckage is in straight line directly east of the Hackett farmhouse, presumably be about a quarter of a mile from the shore. Local opinion is that the water close to the scene of the accident is of a depth of about 20 feet and that there is every likelihood that the ice offshore when moved by a wind from the east will probably drive the wreckage onto the shore. However it is the opinion of the Investigating Officer that if a search was desired, a boat with suitable drag could be used without too much difficulty. The Investigating Officer is finally convinced that there was a danger in the aircraft...the danger was apparent as indicated in the fact that one occupant had his parachute clipped and was able to jump… The final upward climb of the aircraft suggests a possibility that the pilot detecting fire may have strived for altitude, sufficient to enable abandonment of the aircraft by parachute, however it would seem that only one had sufficient time to escape. Since there was no indication of any aerobatics or terminal velocity diving, the Investigating Officer could not vision anything likely to cause the spars to break short of an explosion. There was not much upon which the Investigating Officer could base his conclusions because of the entire absence of the wreckage and lack of concrete evidence.”

In late August 1943, Marjorie received a letter informing her that Paul would be presumed to have died on January 5, 1943.

In October 1944, Mrs. Doolittle, Paul’s mother, received a letter informing her that Paul was promoted to the rank of Flight Sergeant effective December 22, 1942, “but for the intervention of untimely death, are promoted to that rank effective six months from the date of their last promotion.”

In late October 1955, Marjorie received another letter, this time telling her that since Paul had no known grave, his name would appear on the Ottawa Memorial.