April 13, 1923 - October 8, 1942

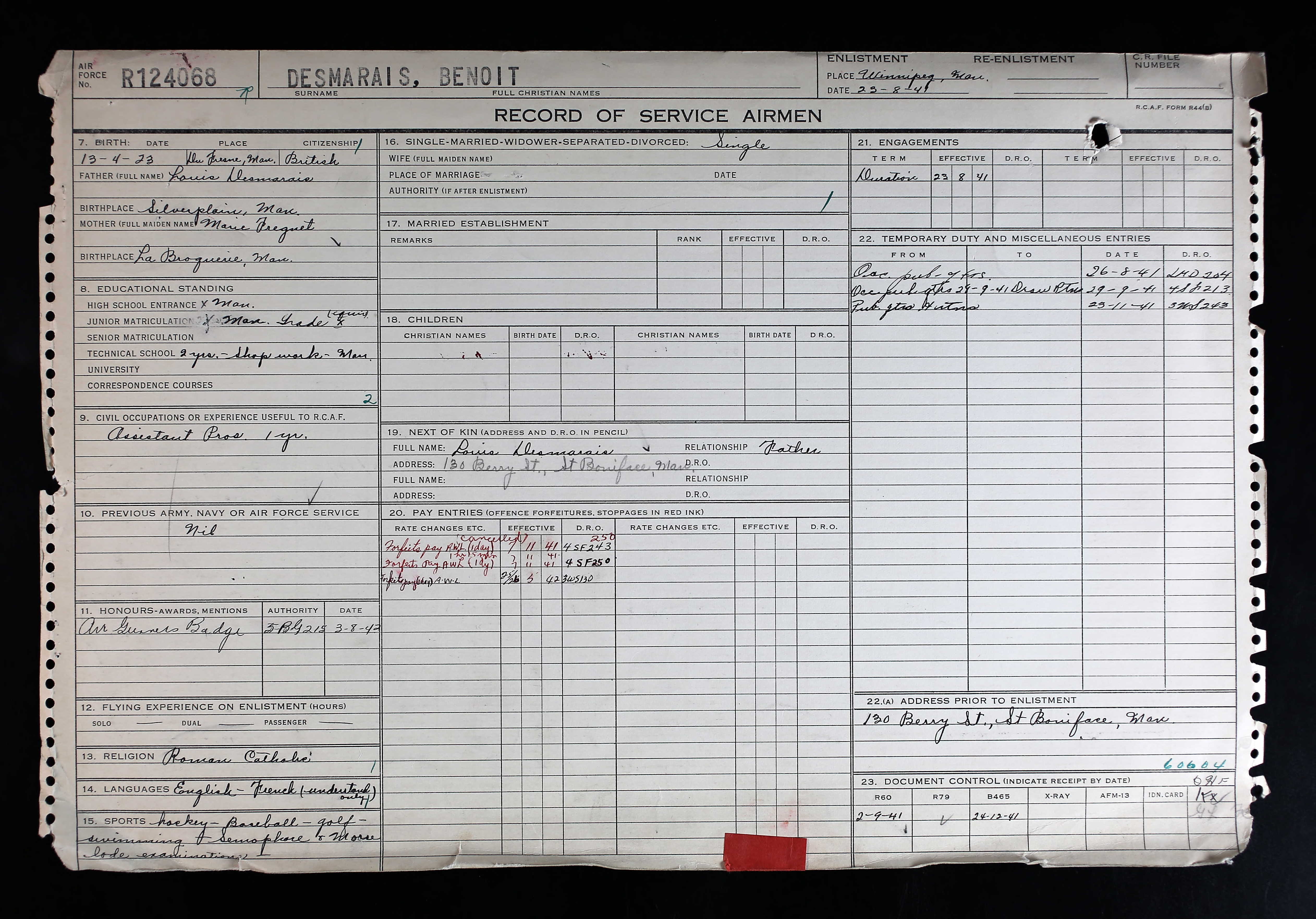

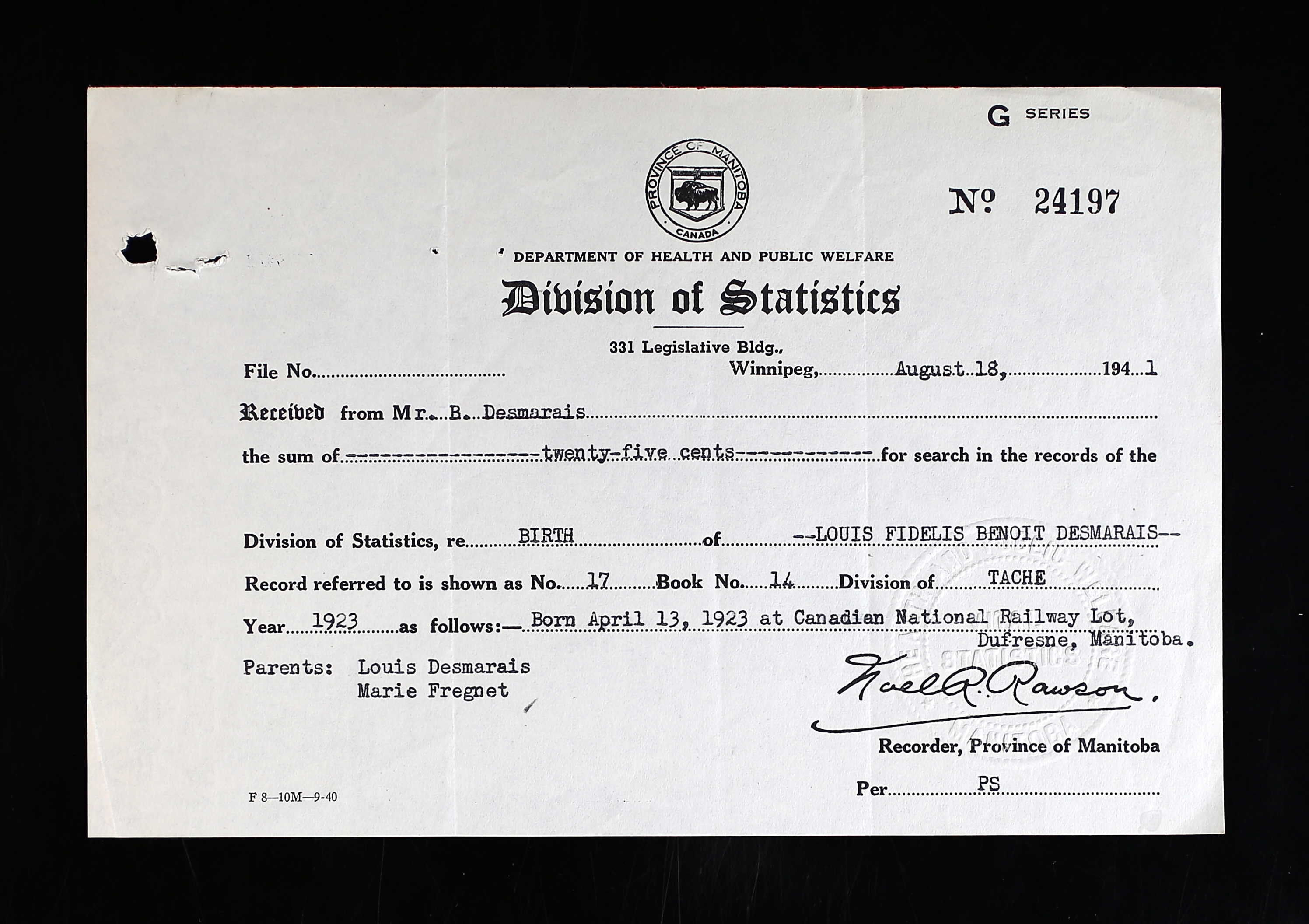

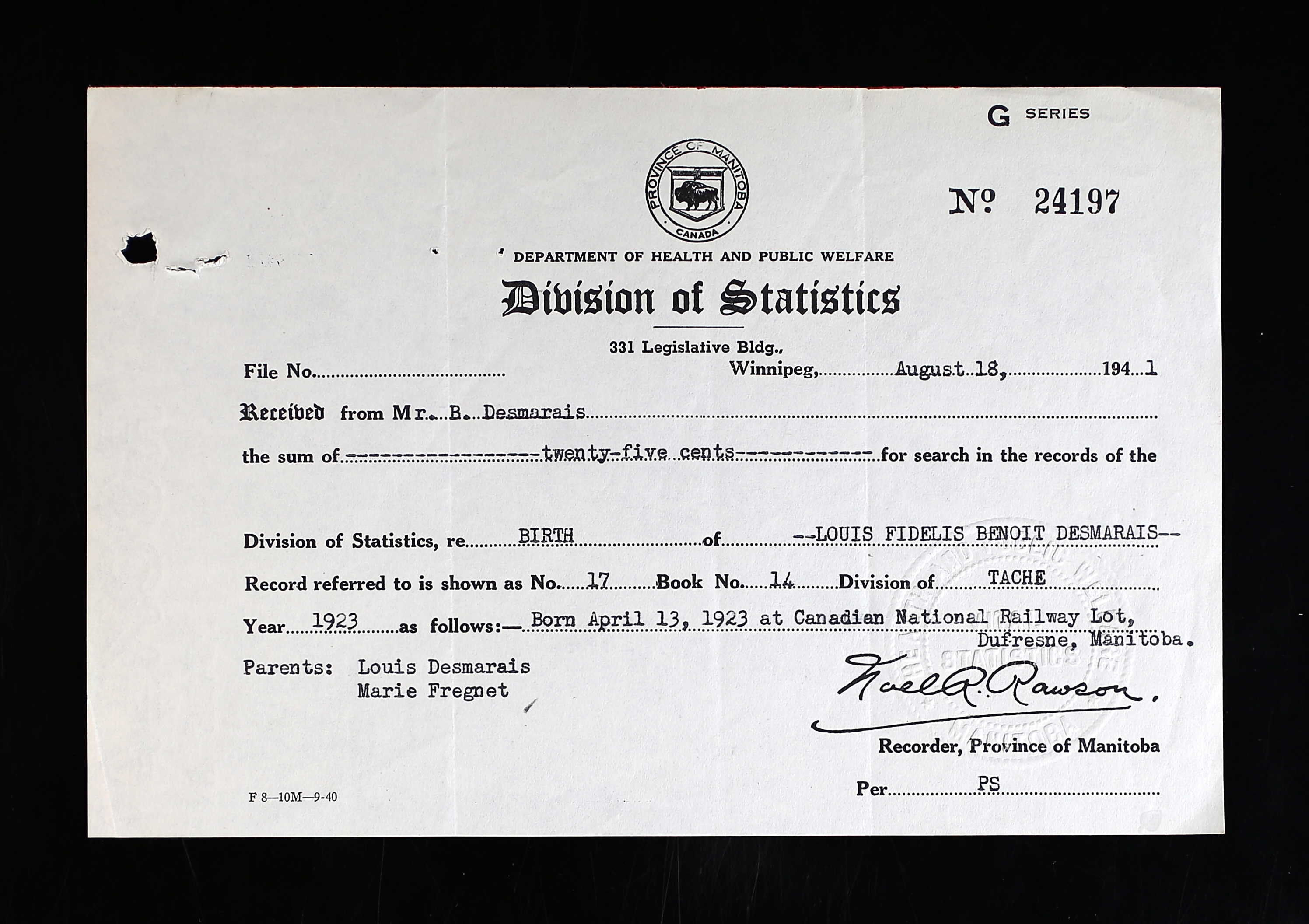

Louis Fidelis ‘Benoit’ Desmarais, born in Dufresne, Manitoba, was the son of Louis Desmarais (1880-1966), retired CNR railroad man, and Marie (nee Freynet) Desmarais (1886-1935) of St. Boniface, Manitoba. He had four brothers, Emmanuel, Fernand, Lucier, and Leon. He had one sister, Antoinette Alary. He was the youngest of his family. The family was Roman Catholic.

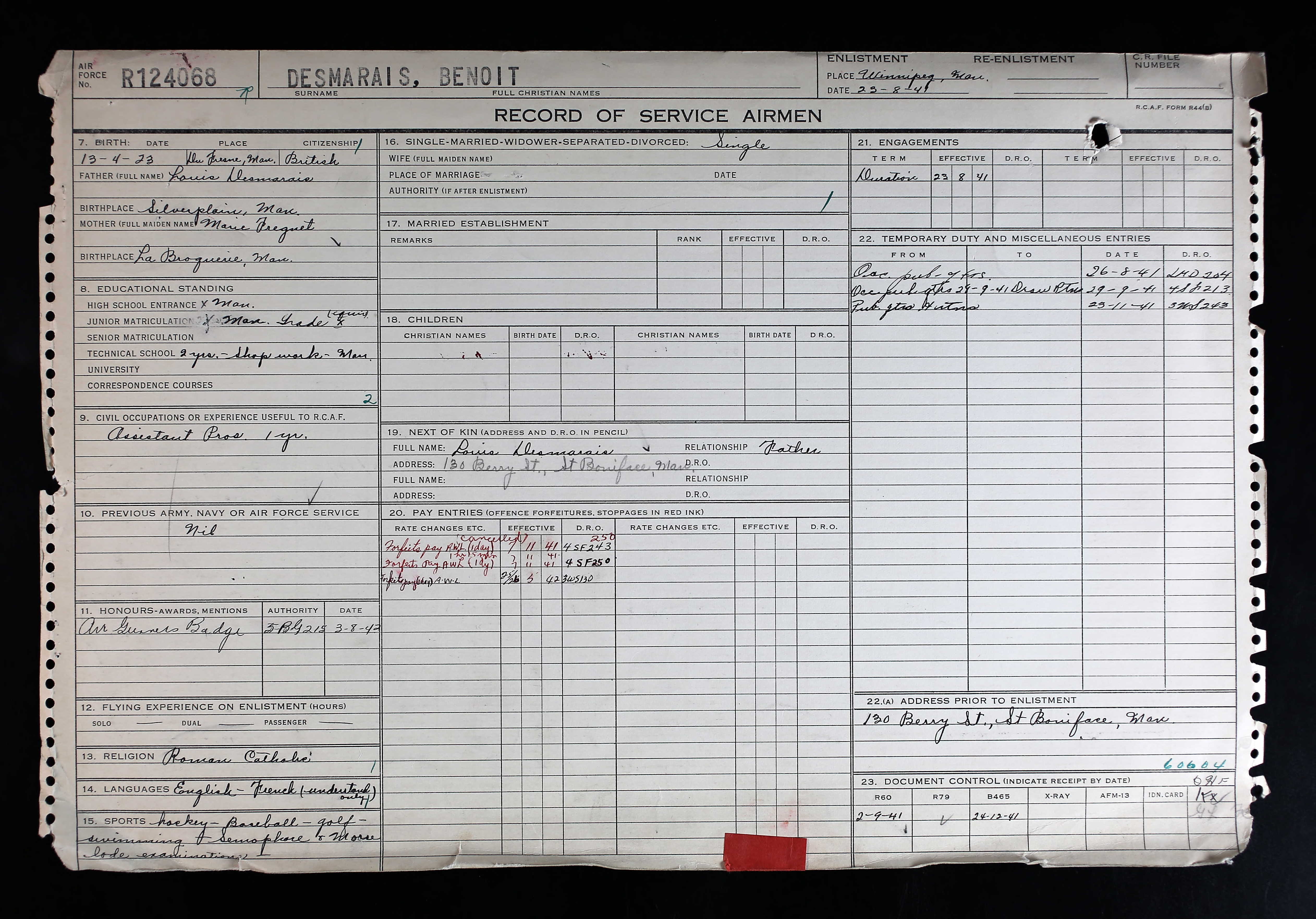

Benoit, also known as Benny, could speak and understand English, only understanding French, according to his attestation papers. His citizenship was “French Canadian.”

He was unemployed at the time of his enlistment with the RCAF in August 1941. He hoped to be a Wireless Operator (Air Crew) and remain involved in wireless after the war. “I have taken Semaphone and Morse Code Examinations under the Government and passed them. Information to his may be secured at Military District No. 10. I have engaged quite extensively in hockey, baseball, golf, swimming and I have played on organized teams in hockey, baseball, and golf.” He was on the Junior team of Provencher School for two season and won the cup in 1936. Prior to the outbreak of war, Benoit looked forward to doing wireless telegraphy on the railroad on which his father worked. “I have joined the Air Force as soon as I finished school to continue on my studies to reach my goal as a Wireless Operator.”

When asked on a questionnaire what led him to join the Air Force, Benoit responded, “To take some course in which would be beneficial to me after the war and naturally to fight for my religion and country.” He felt he “had the necessary qualifications and I am confident that I’ll pull through.” He noted that he might like to be a Fighter Pilot. “My qualifications and my temperament in this line of work would suit me well.”

He liked literature and history the most in school; French and math the least. He had a very set of interview questions within his files.

Benoit’s right thumb was larger than his left. He stood 5’6” tall and weighed 116 pounds. He had brown eyes, black hair and a dark complexion. “Sincere, alert French Canadian. Shouuld do well in aircrew.”

Benoit was sent to No. 2 Manning Depot, Brandon, Manitoba August 23, 1941 until September 27, 1942. He was then taken on strength at No. 4 SFTS, Saskatoon from September 28 until November 22, 1941, until a place opened up for him at No. 3 Wireless School, Winnipeg, Manitoba on November 23, 1941. He remained there until July 4, 1942. He was deferred to Course 35 from Course 33. “Below average.” In his Ground Training: 71.6%, passing. He had four weeks extra instruction.

He earned his Air Gunner’s Badge at No. 5 Bomb and Gunnery School, Dafoe, Saskatchewan, August 3, 1942. He was here from July 4 until August 28, 1942. “An excellent air gunner who takes a keen interest in his work. 3rd in class of 25. in Air Training (Gunnery). Final assessment: 22nd out of 25. 74%. Not recommended for commission.”

November 7, 1941 and May 25/26, 1942, Benoit forfeited a day’s pay for being AWL.

Benoit was sent to No. 36 O.T.U., Greenwood, Nova Scotia for more training.

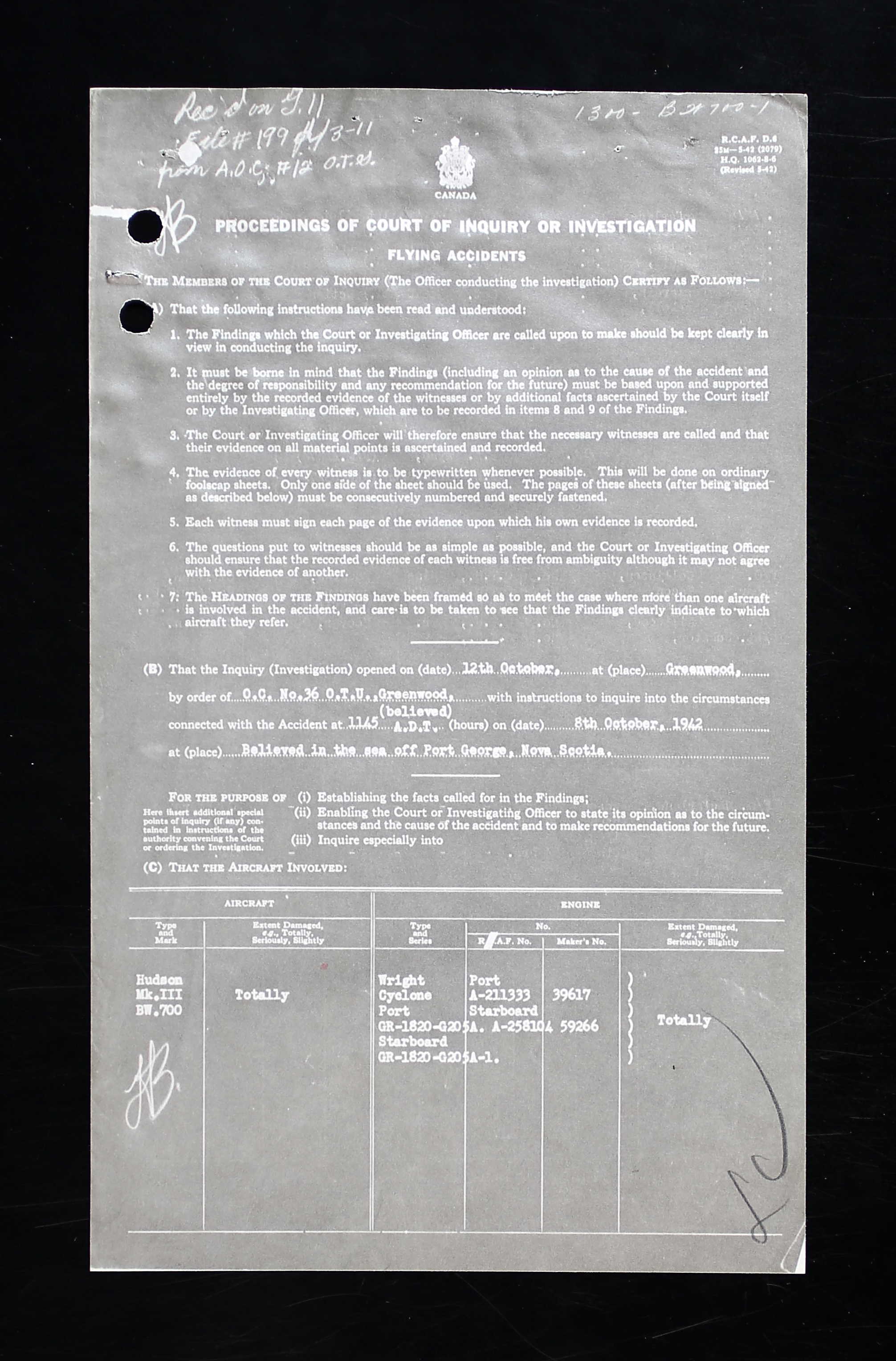

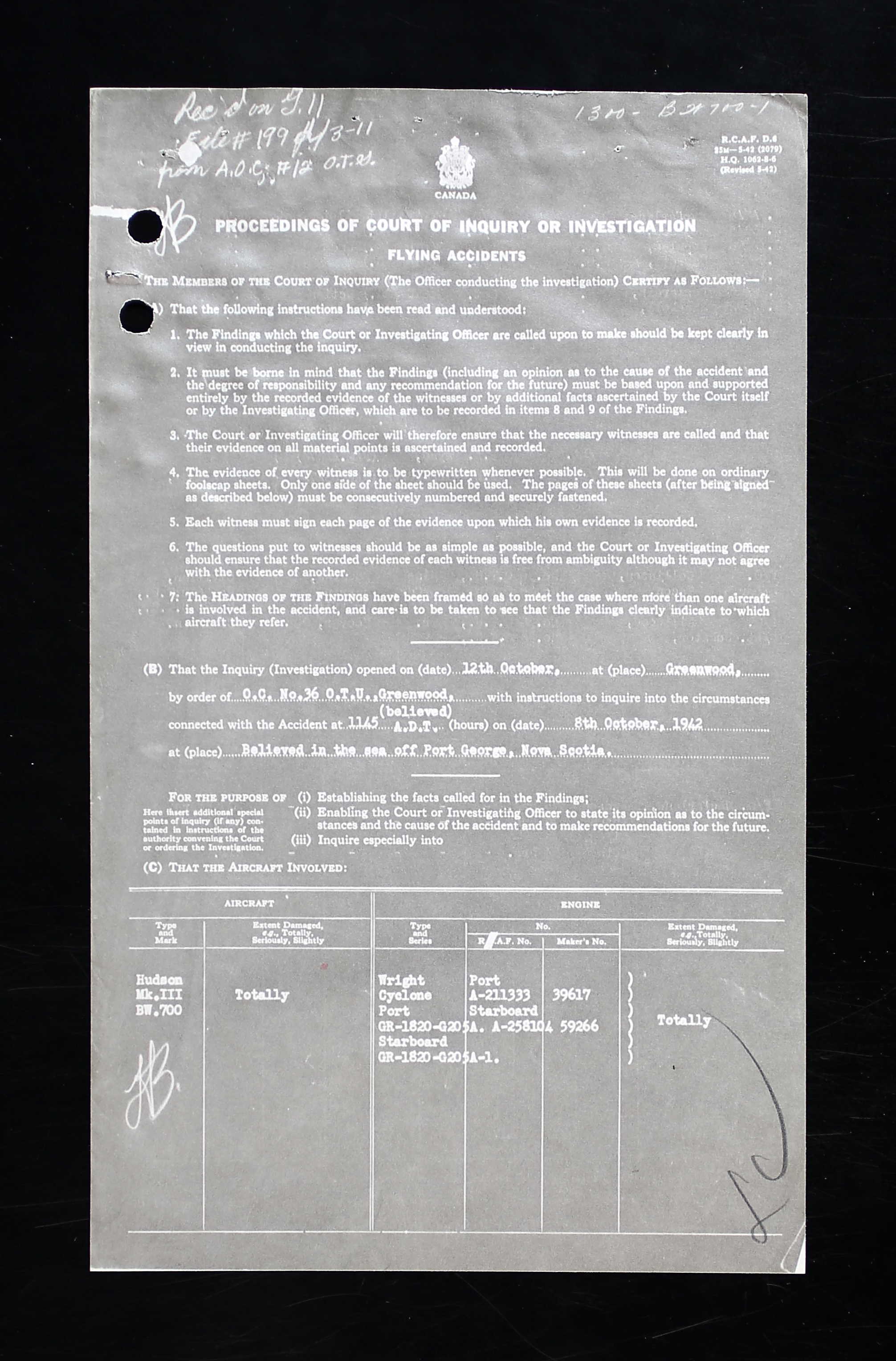

Hudson BW700 was taken on strength by Eastern Air Command March 25, 1942. First assigned to No. 36 O.T.U. RCAF Station Greenwood; crashed near Port George, NS, on the Bay of Fundy, 9 miles west of Greenwood at 12:00 on October 8, 1942. Was reported missing on air to sea firing exercise, all crew missing, presumed killed.

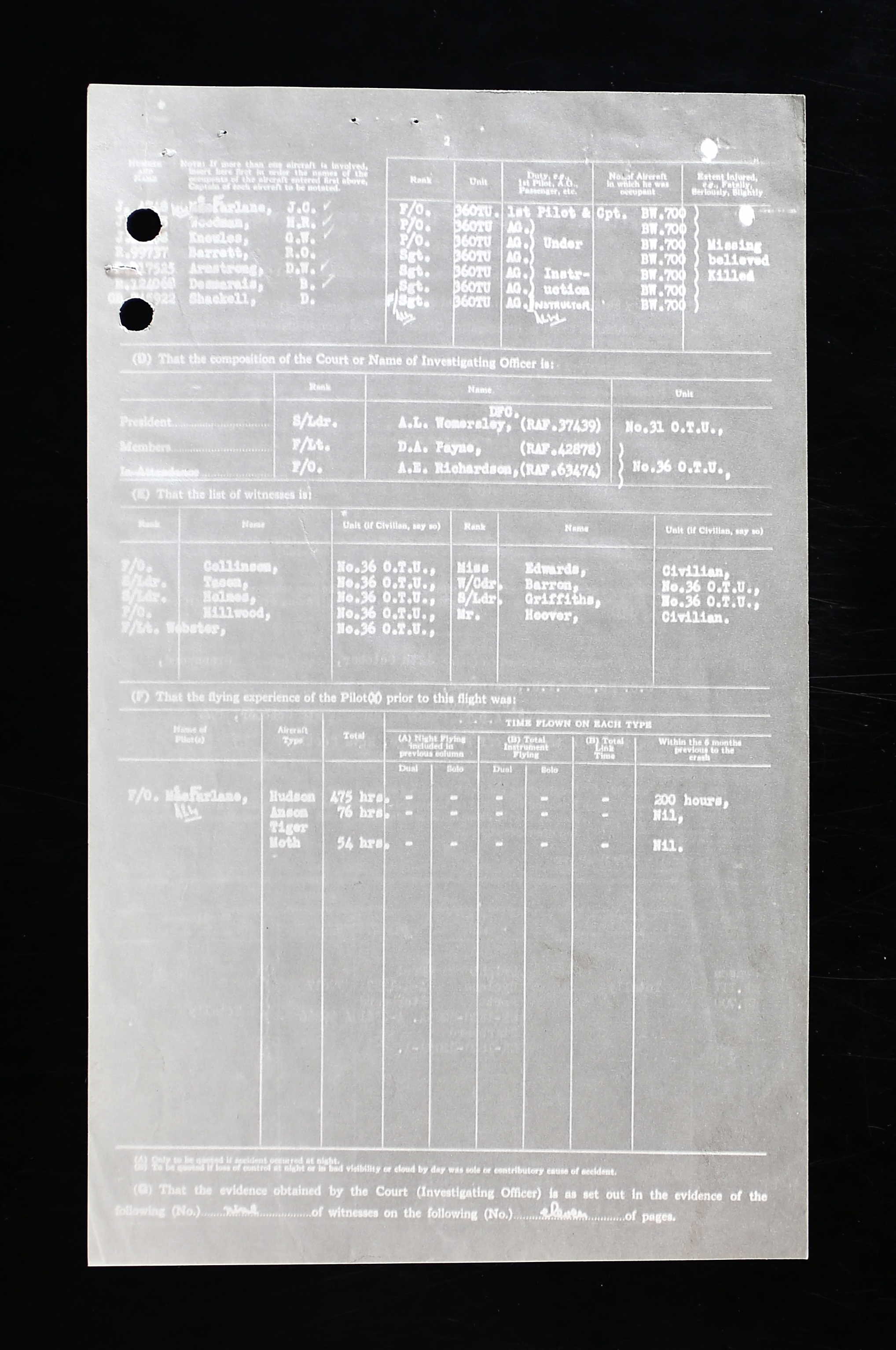

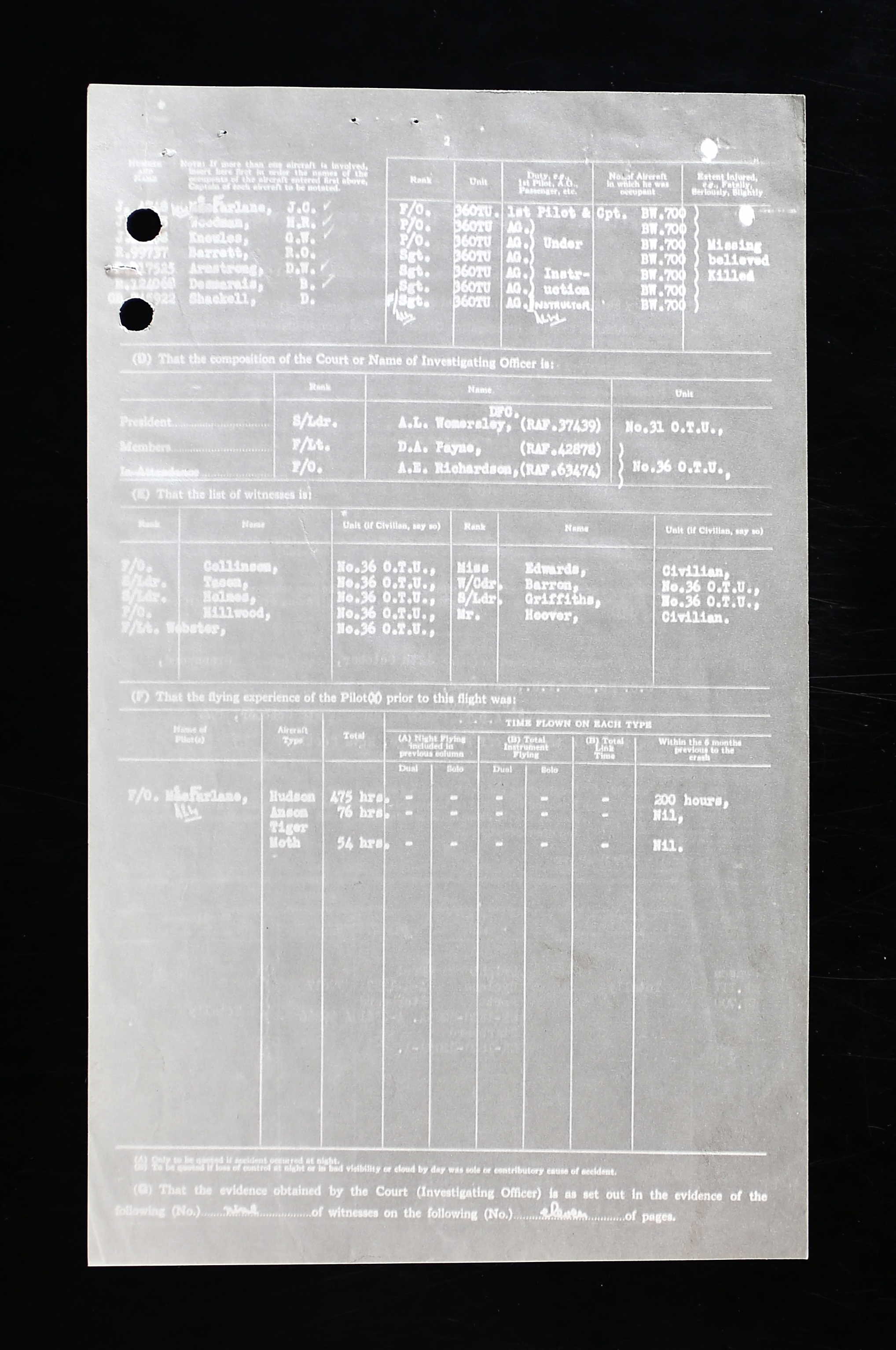

Aircrew: • Sergeant Douglas Wilson Armstrong, R117525 • Sergeant Robert Oliver Barrett, R99737 • Sergeant Benoit Desmarais, R124068 • Pilot Officer George William Knowles, J12998 • Flying Officer Jack Campbell McFarlane, J4748, Staff Pilot • Flight Sergeant Daniel Shackell, 745922 RAF, Staff Armament Officer, son of William and Ellen Shackell, husband of Violet, London, England • Pilot Officer Henry Raymond Woodman, J13145

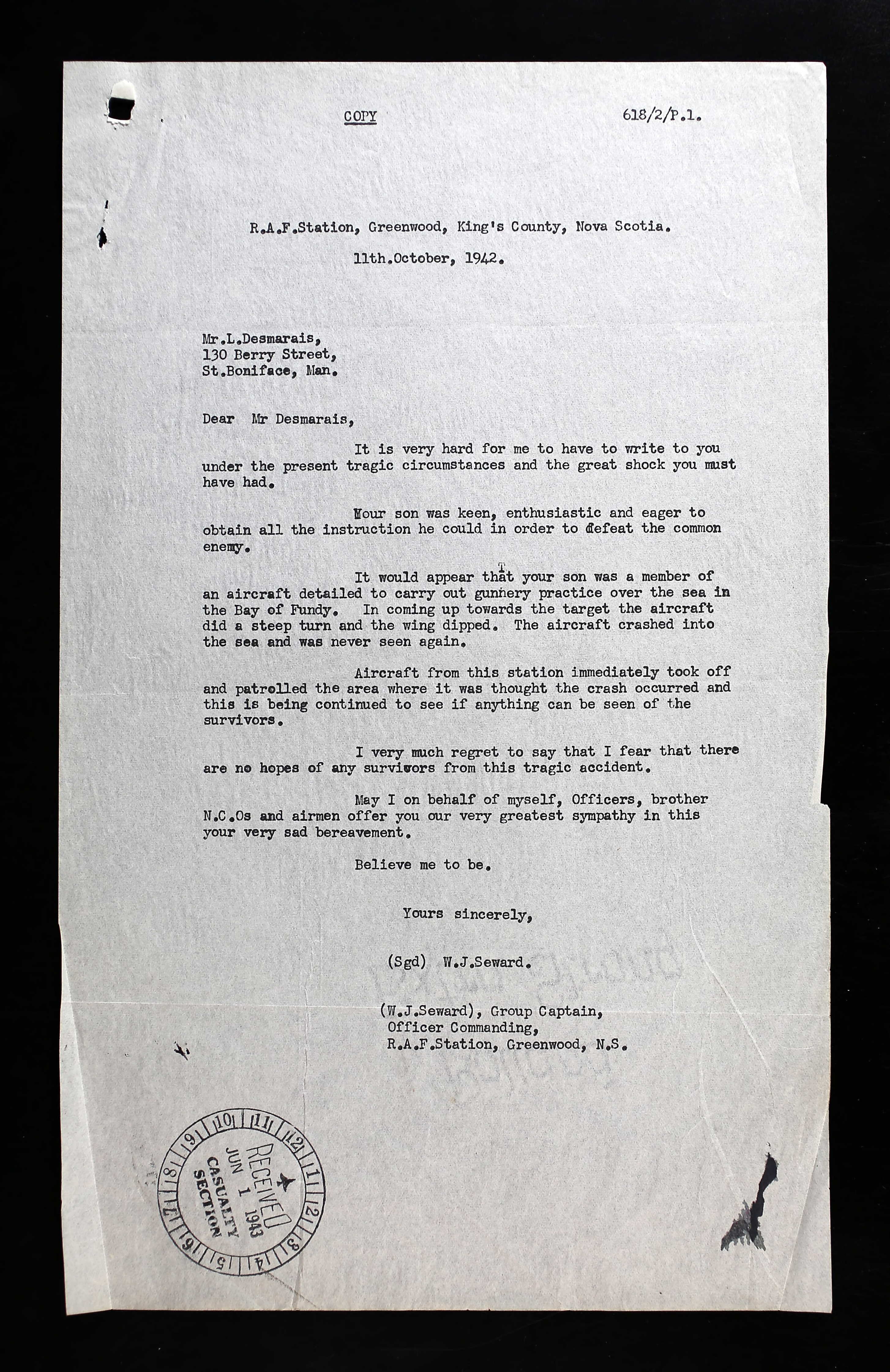

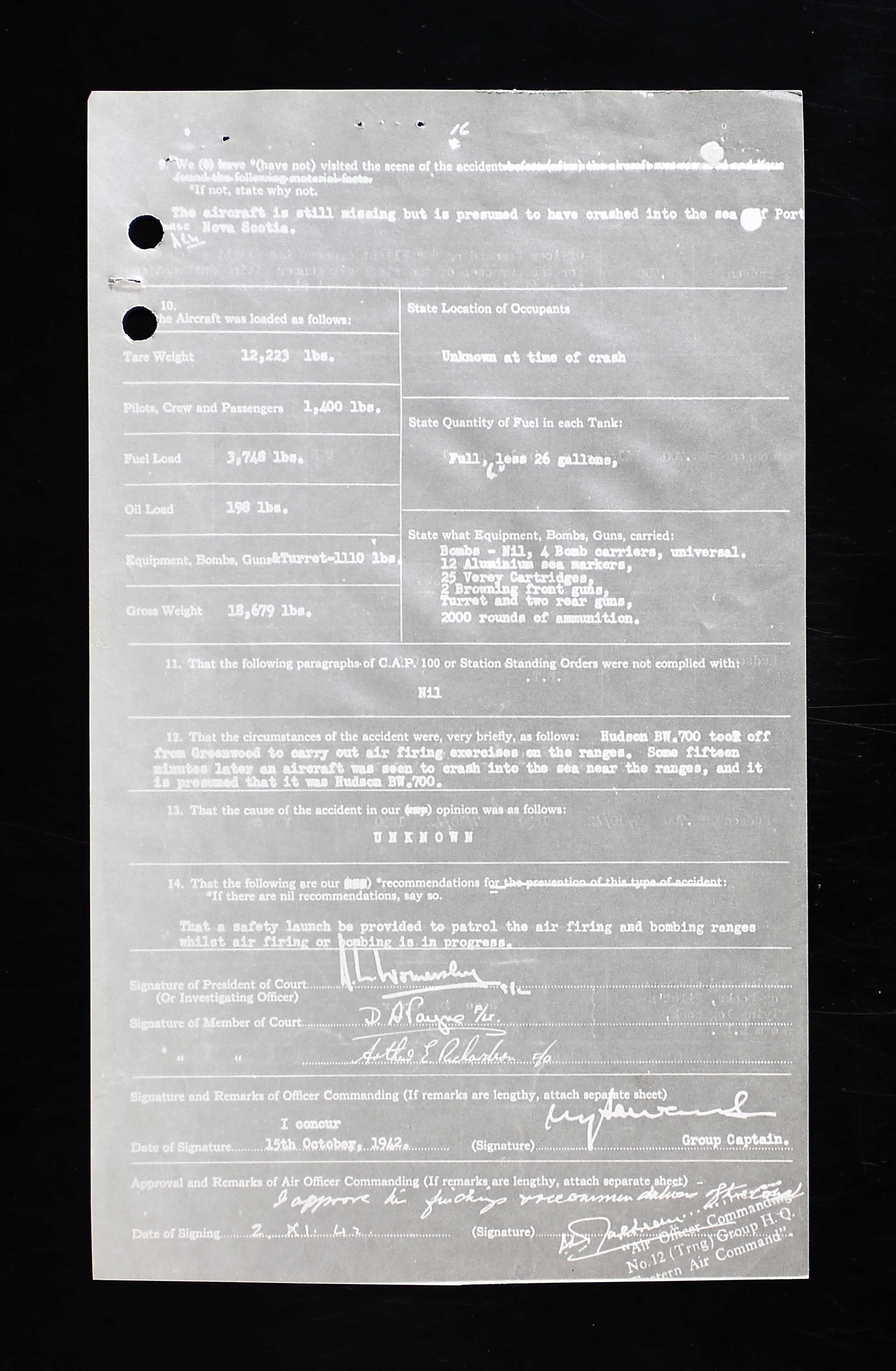

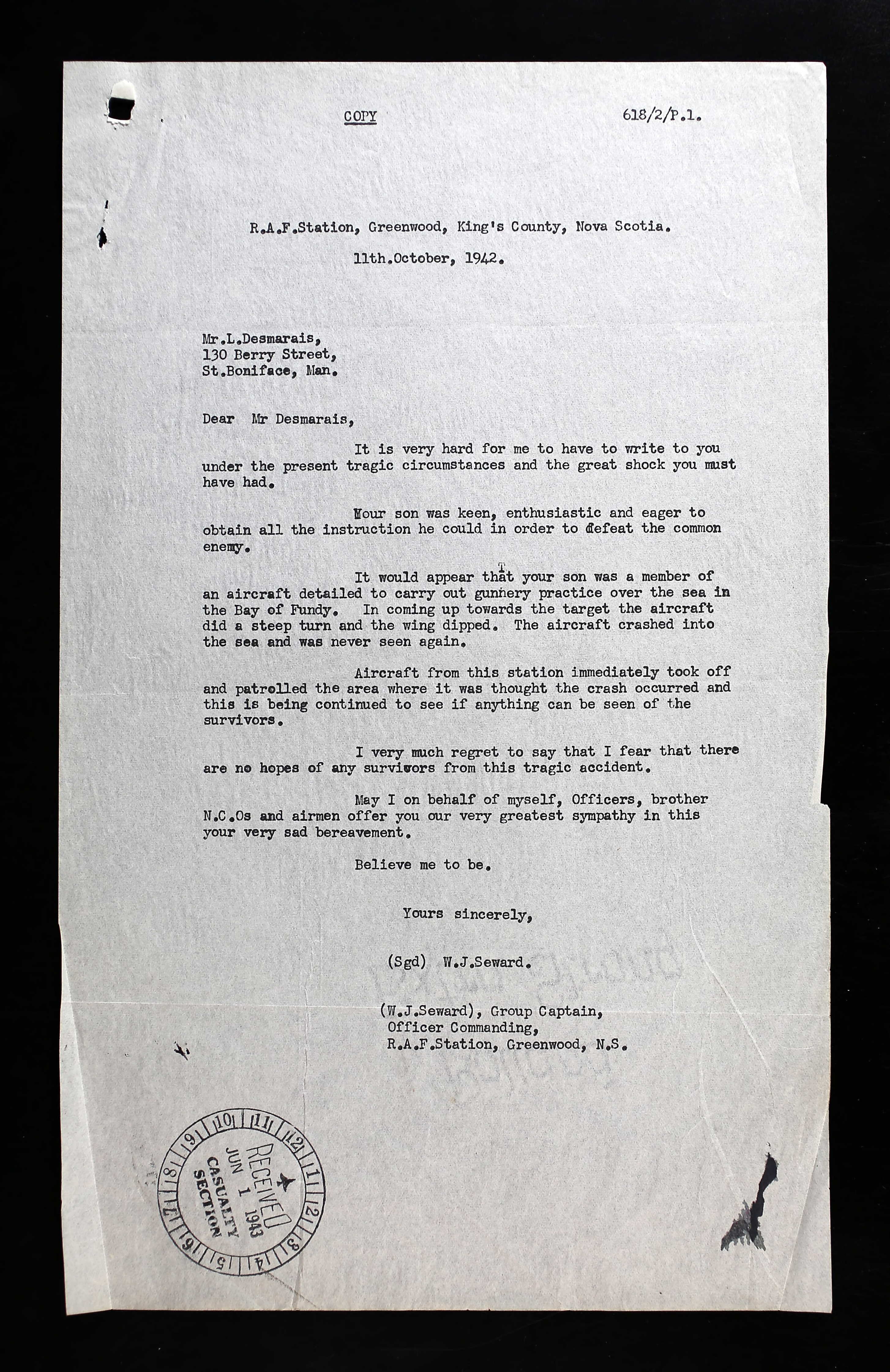

On October 11, 1942, a letter written by Group Captain W. J. Seward to Mr. Demarais: “It is very hard for me to have to write to you under the present tragic circumstances and the great shock you must have had period your son was keen, enthusiastic, and eager to obtain all the instruction he could in order to defeat the common enemy. It would appear that your son was a member of an aircraft detail to carry out gunnery practice over the sea in the Bay of Fundy. In coming up towards the target, the aircraft at a steep turn and the wing dipped. The aircraft crashed into the sea and was never seen again. Aircraft from the station immediately took off and patrol the area where it was thought the crash occured and this is being continued to see if anything can be seen of the survivors. I very much regret to say that I fear that there are no hopes of any survivors from this tragic accident. May I, on behalf of myself, officers, brother NCOs, and airmen offer you our very greatest sympathy in this your very sad bereavement.”COURT OF INQUIRY sat from October 12 to October 14, 1942.

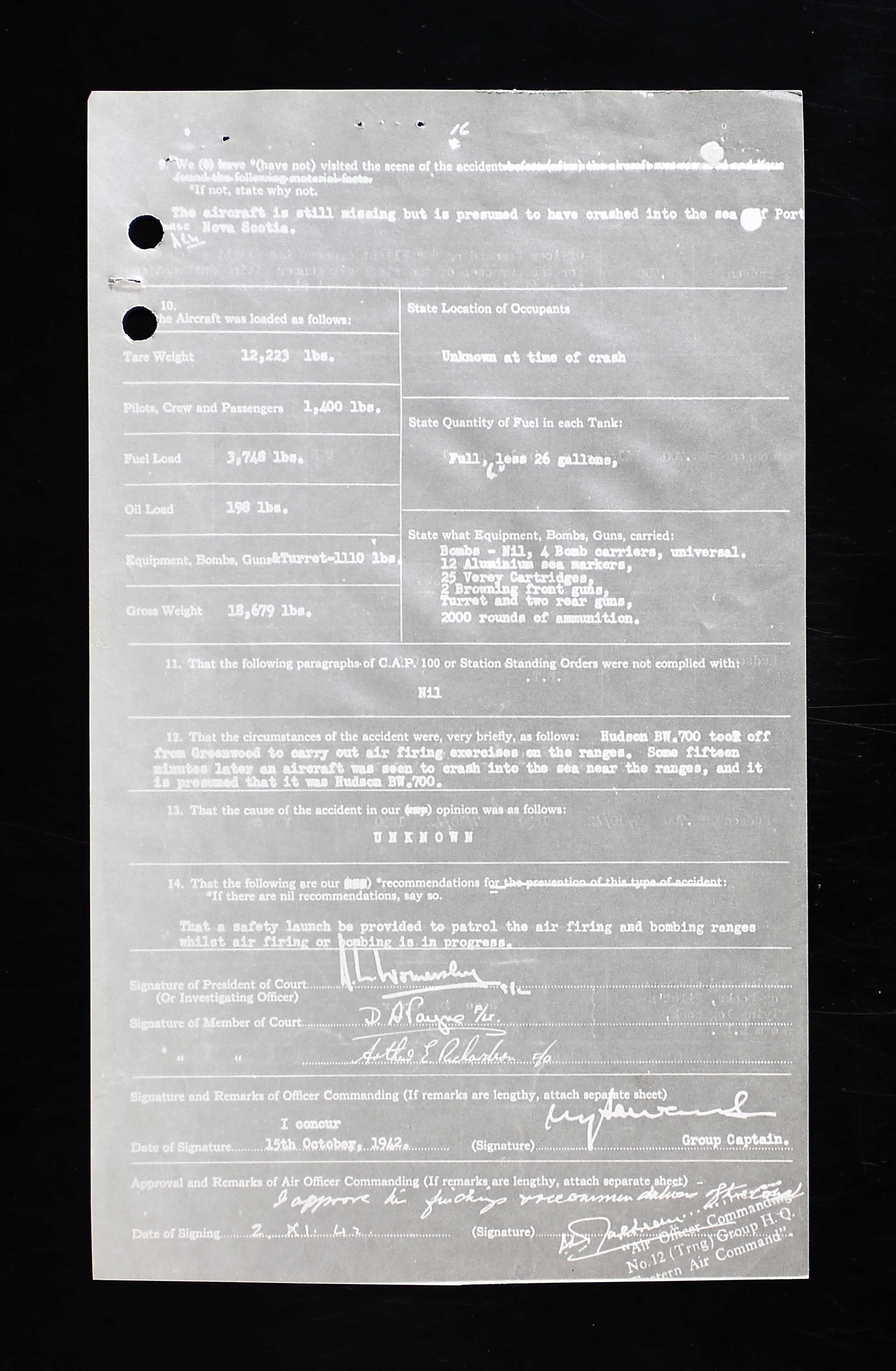

“Purpose of the staff air gunner giving instruction to pupil air gunners in rear turret air firing at sea markers. The aircraft is still missing but is presumed to have crashed into the sea off Port George, Nova Scotia. Hudson BW700 took off from Greenwood to carry out air firing exercises on the ranges. Some fifteen minutes later an aircraft was seen to crash into the sea near the ranges, and it is presumed that it was Hudson BW700.”

FIRST WITNESS: Flying Officer Kenneth Lloyd Collinson, 87454 Duty Pilot: “On the 8th of October 1942, at approximately 1150 hours, whilst carrying out my duties as duty pilot in the control tower at No. 36 O.T.U. I received a telephone call from a woman stating she was a storekeeper at Port George and that a Miss Josephine Edwards had seen an aircraft dip low over the water, about a mile off land from Port George and then disappear. I inquired from the caller whether she could give any further details, but she was unable to do so. I therefore told her that I would send someone out to Port George and in the meantime if she received any further information to advise me immediately by telephone.

“Immediately after this telephone conversation with the storekeeper, I informed the Chief Inspector, Wing Commander Barron, of the details I had just received, and then I dispatched the ambulance to Port George with orders to report to the storekeeper. I then made inquiries at the flights and ascertain from B Flight that they had an aircraft carrying out air firing on the ranges at that moment. Arrangements were made and Squadron Leader Tacon took off at 1200 hours in a Hudson to search an area off Port George. A Lysander with Squadron Leader Holmes followed on a similar mission at 1205 hours.

“At 12:45 hours, a message was received from the medical officer, Flight Lieutenant Webster, who had accompanied the ambulance stating that he was in Port George and on making inquiries had ascertained from several witnesses that an aircraft was seen to hit the water about a mile offshore from Port George and then disappear from view. The medical officer was instructed to obtain the names and addresses of all witnesses and if possible, to obtain any further information.”

The second witness, Squadron Leader Ernest William Tacon, DFC, AF, RAF, 36196, (POW by September 1944, d. 2003) stated that he had observed several pieces of green debris, and oil patch to be 100 yards in length, and what appeared to be a partially submerged portion of a dinghy but no sign of human bodies. He circled the area for about 15 minutes without seeing any other sign of wreckage and returned to base./

The third witness, S/L Arthur Ray Holmes, RAF, 39524 stated that Hudson BW 700 was to carry out splash firing at aluminum sea markers in the Margaretville firing ranges. The aircraft took off from Greenwood at 11:30 hours. He also noticed an oil slick about 3 miles out to sea extending for about 300 feet parallel to the coastline. He carried out a low search for signs of evidence of a crashed aircraft and observed several small green objects floating in the water which resembled portions of the interior of a Hudson aircraft. He observed also what appeared to be a small portion of a dinghy sticking out of the water but no visible signs of human bodies or other wreckage so he returned to the aerodrome and reported what he had seen. At 1800 hours he accompanied a party in a boat to the estimated position where he had previously seen the oil slick but owing to the roughness of the sea and failing light, it was impossible for him to distinguish any sign of wreckage or the oil slick and the boat party returned at 1915 hours. During his flight of this aircraft on a similar firing exercise on the 8th of October 1942 at 0940 to 1105 hours, flown by Flying Officer McFarland, the aircraft behaved perfectly normally and was in all respects fully serviceable.

The fourth witness, P/O Peter Hillwood stated that the weather conditions over the area remained good for the whole day but towards the evening the sea became quite rough.

Miss Josephine Agnes Edwards of Port George stated that on the 8th of October 1942 about 11:30 hours, “I observed from my kitchen window a twin engine aircraft approaching from the direction of Greenwood, and when over Port George, the aircraft turned and flew easterly for a short distance. She then turned apparently and flew in a westerly direction, for the next time I noticed the aircraft, she was approaching the village from the west, parallel to the coastline and approximately about one mile offshore. When opposite my residence, I noticed the aircraft was doing a very steep bank close to the water. My impression at that moment was at the aircraft would not right itself and within a few seconds I saw her strike the water with one wing. There was a terrific splash and the aircraft disappeared from my view from the kitchen window. I then went outside and gave the alarm to Mr. Edward McKenzie who in turn went to the general store and asked Mrs. Margaret Rafuse to telephone Greenwood. The actual time of the crash was approximately 1140 hours and at about 1200 hours, I noticed an oil streak in the position where the aircraft was seen to disappear. So far as I know there were no other eyewitnesses who saw the actual crash.”

The seventh witness, W/C Oswald James Milman Barron, DFC, RAF, 33217 (died 1944, flying a Mosquito - name at Runneymede) stated that the quickest method of getting a boat out to the scene of the reported crash was to take a mobile crane and twenty men from the station in order to assist in launching a laid-up boat that was available at Margaretville, “however it was not until 1800 hours that evening that the boat was launched, and although I accompanied the boat to the scene of the reported crash, by that time there was no evidence of a crash anywhere to be found in the vicinity. I gave instructions to all crews of aircraft flying in that vicinity during the 9th and 10th of October 1942 to keep a sharp lookout for any sign of wreckage but nothing was seen. As soon as the reports from the crew detailed to search the area immediately following the report of a crash came to hand, and in view of the fact that Hudson BW700 was the duly aircraft from this unit detailed to fly in the Port George vicinity at that time, I was convinced that Hudson BW700 had crashed into the position reported.”

The eighth witness, S/L Allan Richmond Lloyd Griffiths, RAF, 37398, stated that they did not have a safety boat for No. 36 O.T.U. Air Firing Ranges. On the 25th of June 1942, he had written to the C/I and pointed out the “complete lack of a marine craft section for this Unit. However, during the summer months, it was possible to obtain local facilities in an emergency for air sea rescues, but as from about October 1, 1942, the local boats were pulled up for winter. Boats operate from Parker Cove, some 30 miles from the Air Firing ranges, during the winter, but there is no guarantee they would be available if required at short notice.”

CAUSE: Unknown. RECOMMENDATIONS: That a safety launch be provided to patrol the air firing and bombing ranges whilst air firing or bombing is in progress.

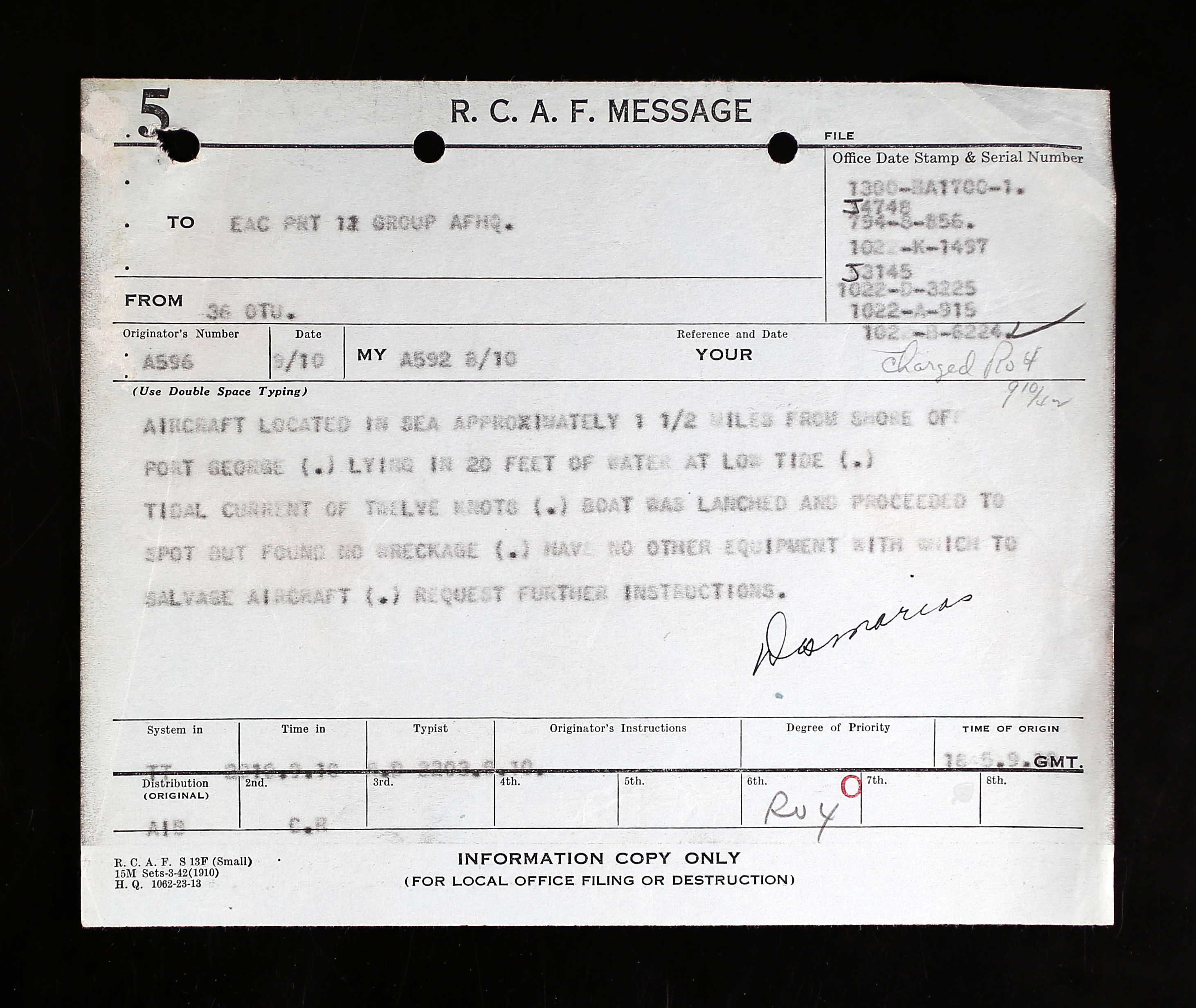

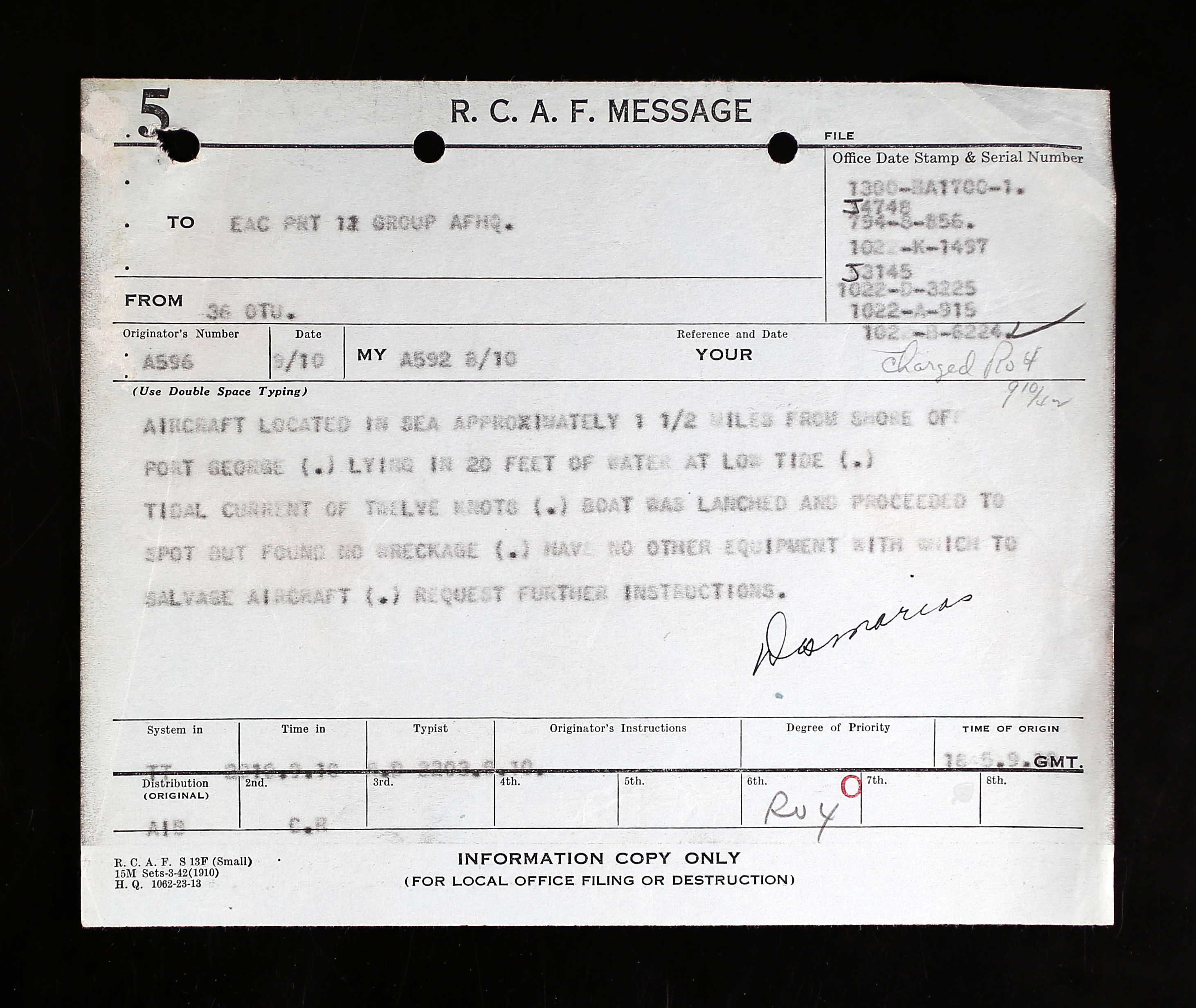

“Hudson BW700 was located in the sea approximately 1 ½ miles from shore off Port George, lying in 20 feet of water at low tide. Tidal current of 12 knots, boat was launched and proceeded to spot but found no wreckage. Have no other equipment which to salvage aircraft.”

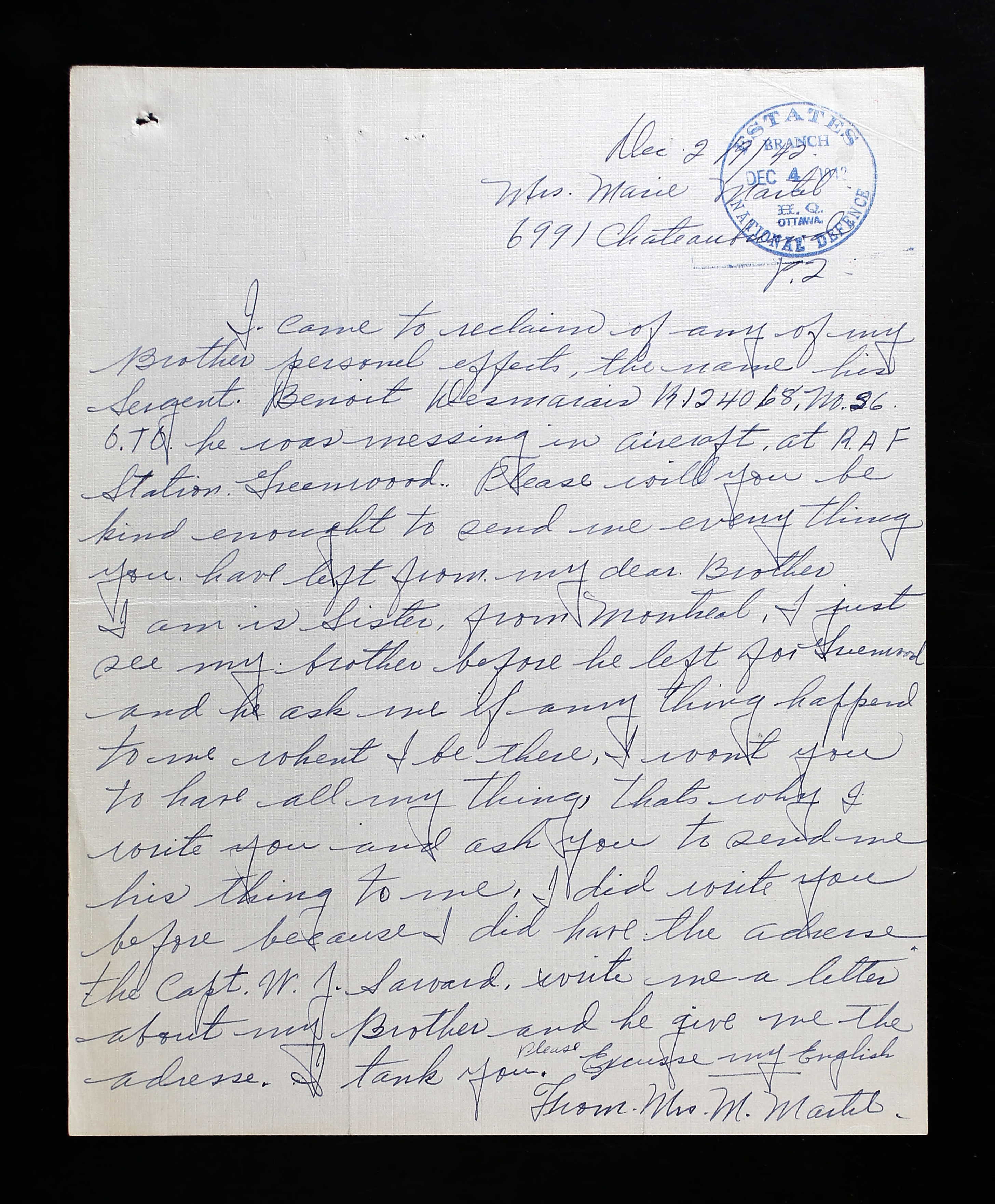

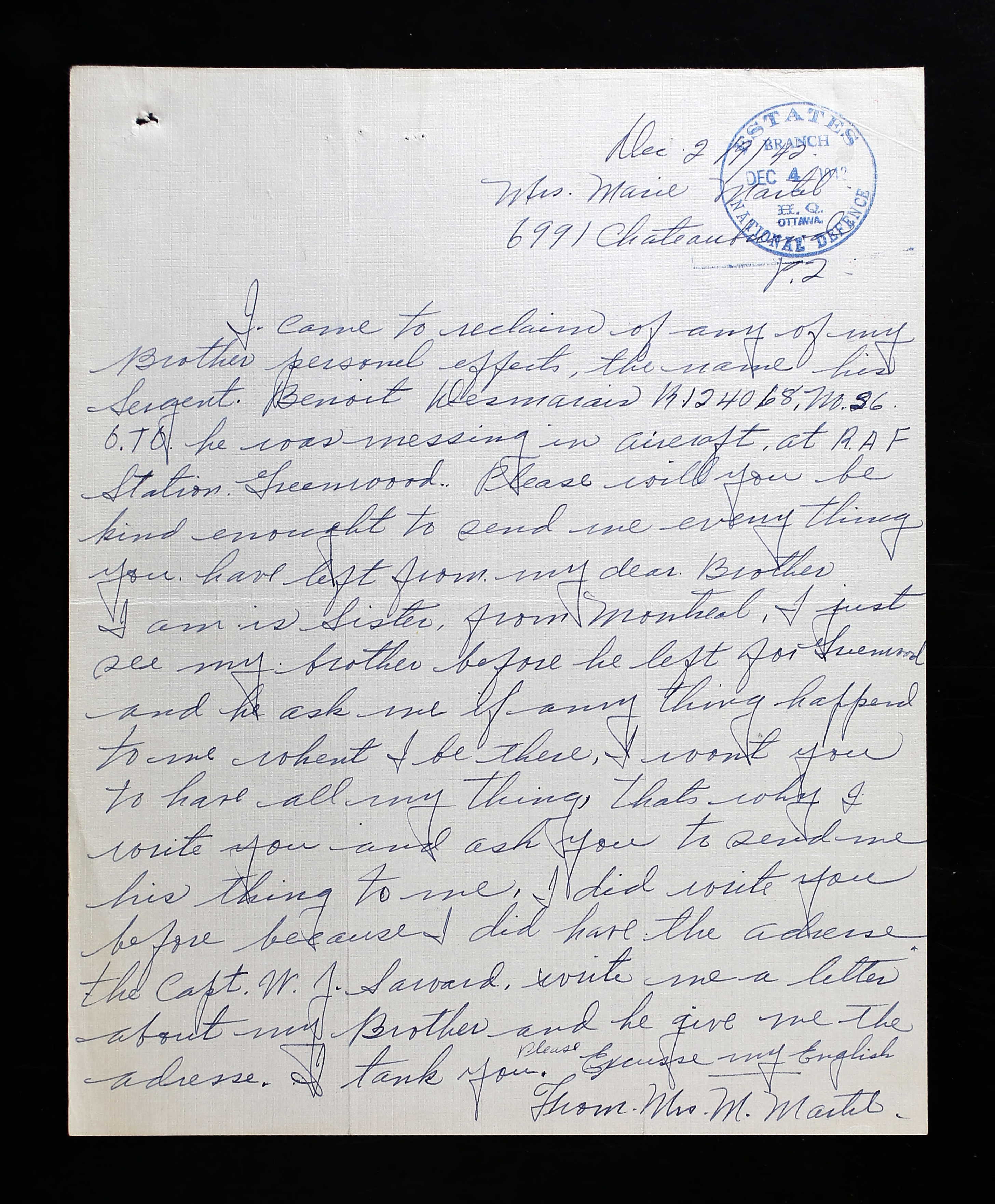

On December 2, 1942, a woman claiming to be Benoit’s sister, Marie Martel of Montreal, wrote to the Estates Branch asking for her brother’s possessions. “Please will you be kind enough to send me everything you have left from my dear brother. I am his sister from Montreal. I just saw my brother before he left for Greenwood and he asked me, ‘if anything happened to me when I went there, I want you to have all my things.’ That is why I am writing to you….I did not write you before because I did not have the address…please excuse my English.” [See original letter above.]

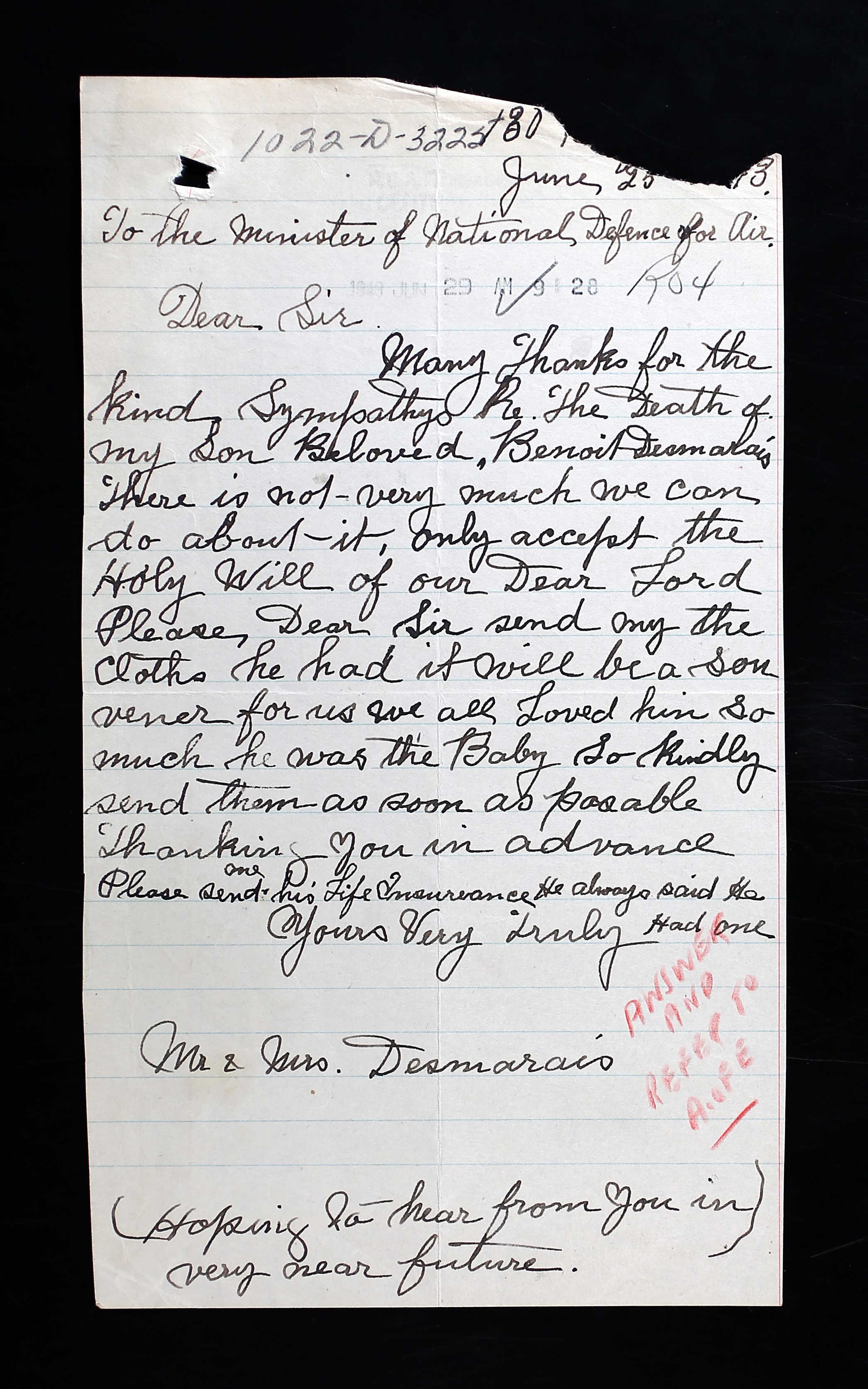

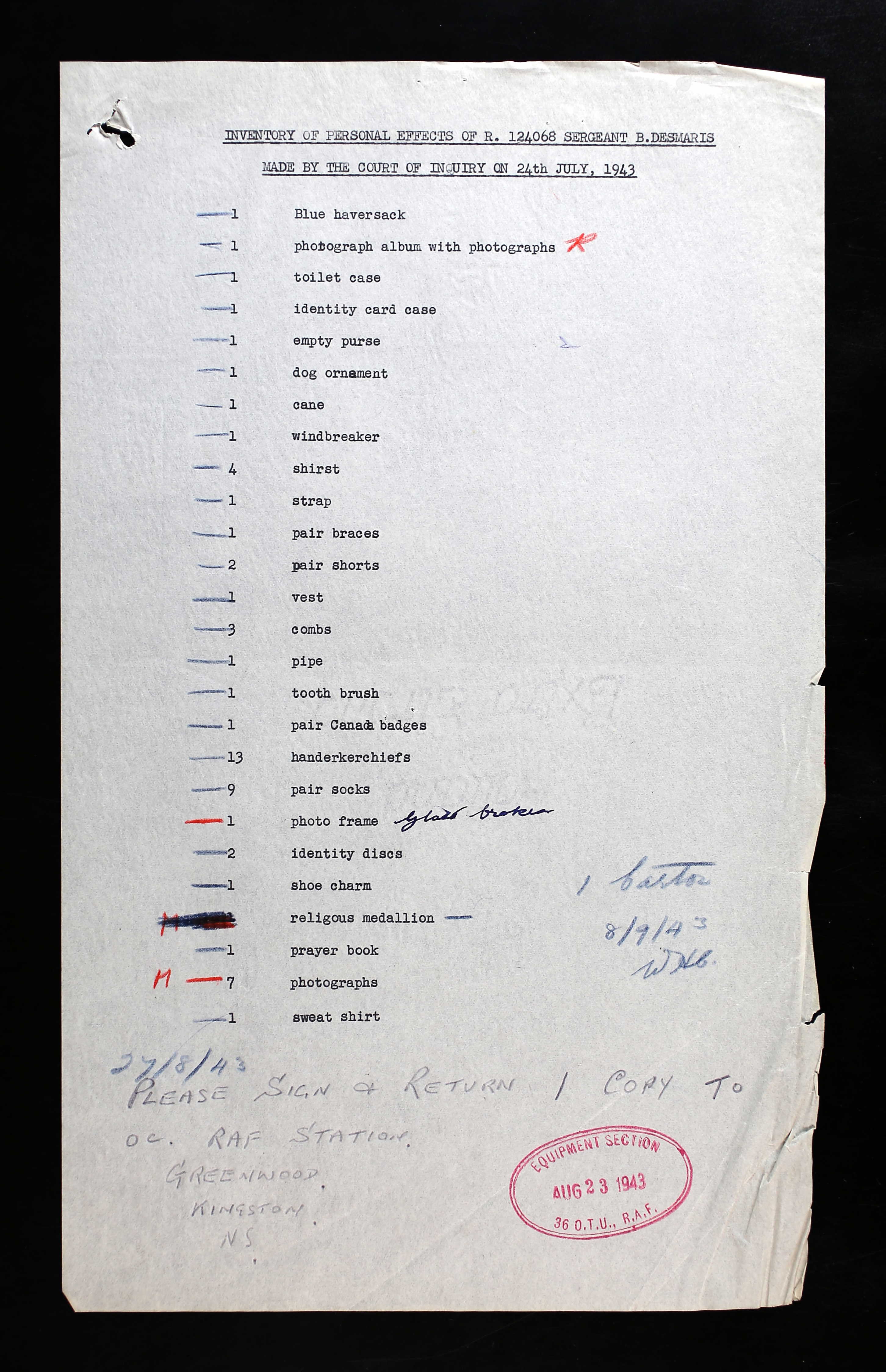

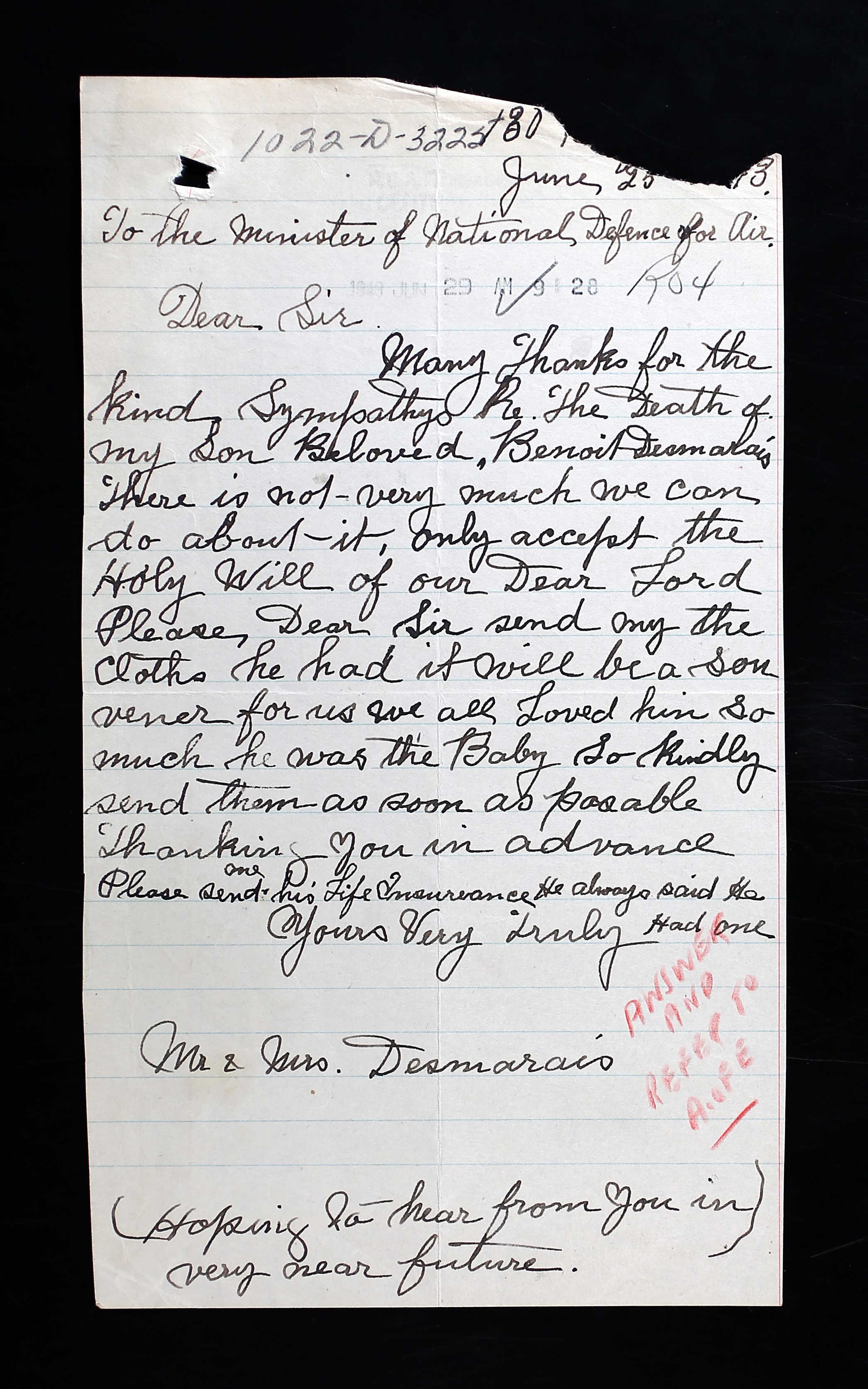

In late June of 1943, Mr. and Mrs. Desmarais wrote a letter to the Minister of National Defence for Air: “Dear Sir, Many thanks for the kind sympathy Re: the death of my son, beloved Benoit Desmarais. There is not very much we can do about it, only accept the Holy Will of our Dear Lord. Please, Dear Sir, send me the clothes he had. I will be a souvenir for us. We all loved him so much. He was the baby. So kindly send them as soon as possible. Thanking you in advance. Please send me his life insurance. He always said he had one. (Hoping I hear from you in the very near future.”

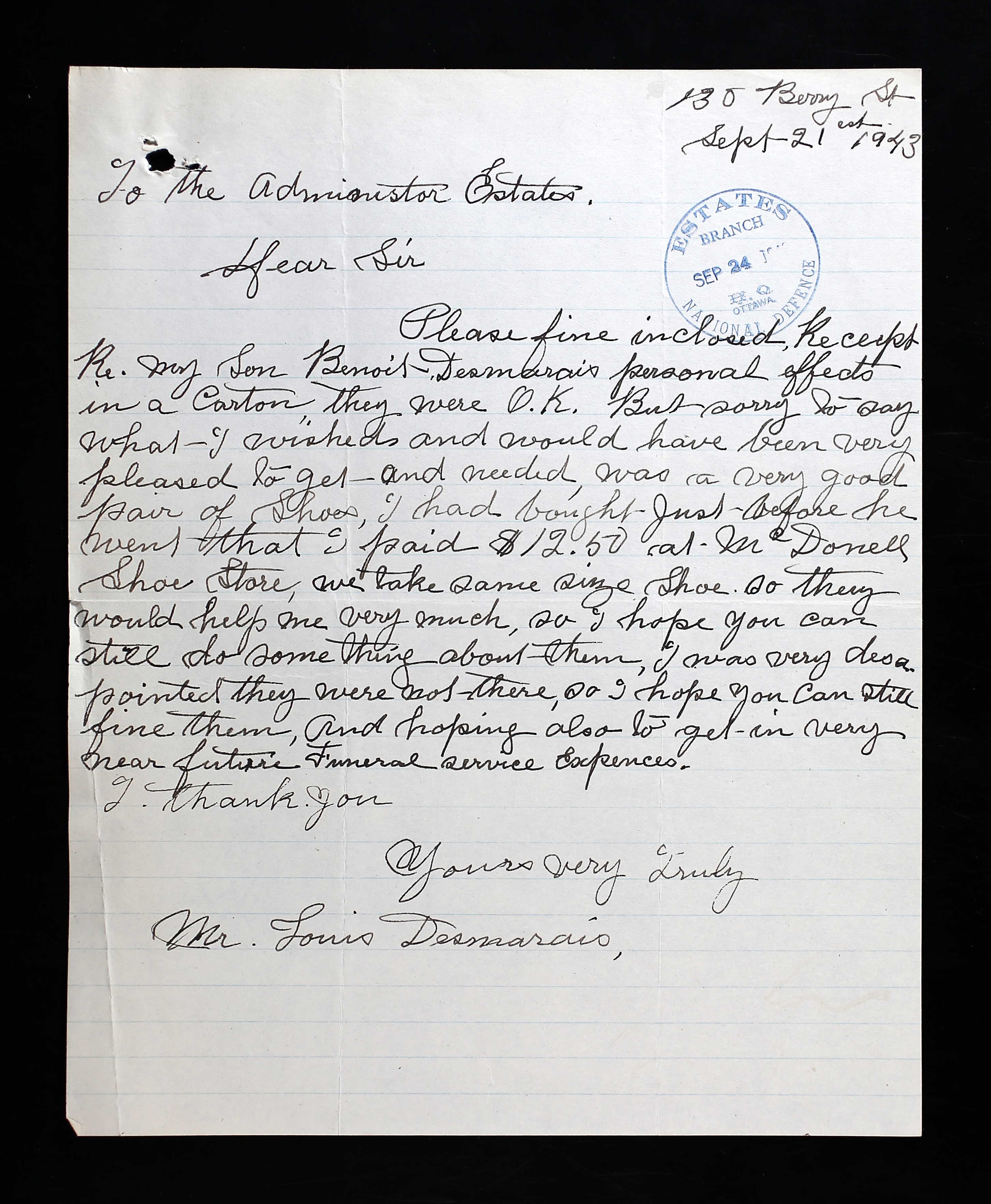

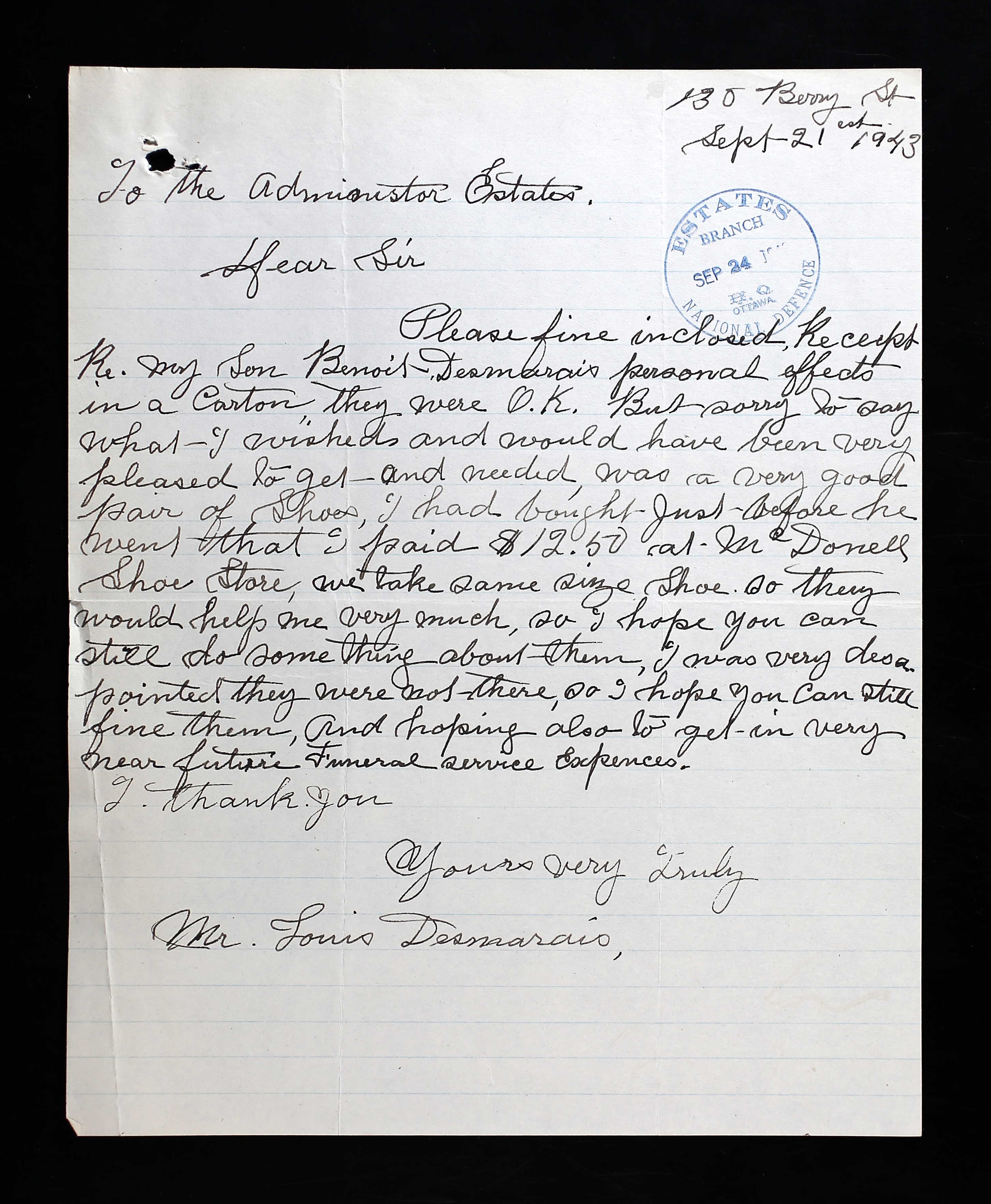

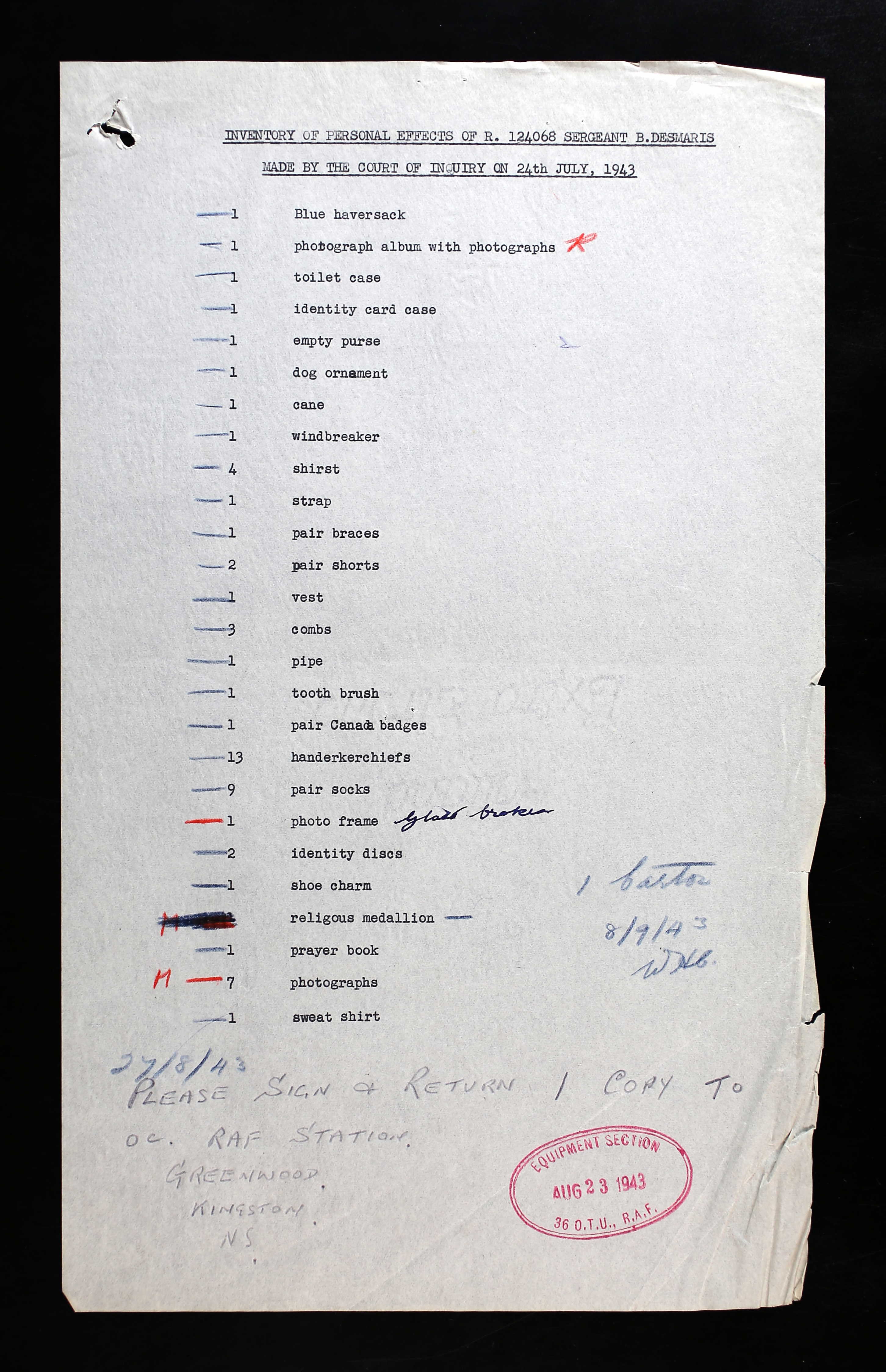

In September 1943, Mr. Louis Desmarais wrote again, this time to the Administrative Estates: “Please find enclosed receipt RE: my son Benoit Desmarais’s personal effects in a carton. They were okay. But sorry to say that I wished and would have been very pleased to get and needed was a very good pair of shoes. I had bought just before he wend that I paid $12.50 at Macdonald Shoe Store. We take same size of shoe, so the would help me very much, so I hope you can still do something about them. I was very disappointed they were not there, so I hope you can still find them. And hoping also to get in very near future, funeral service expenses. I thank you.” He had paid $25 for funeral expenses.

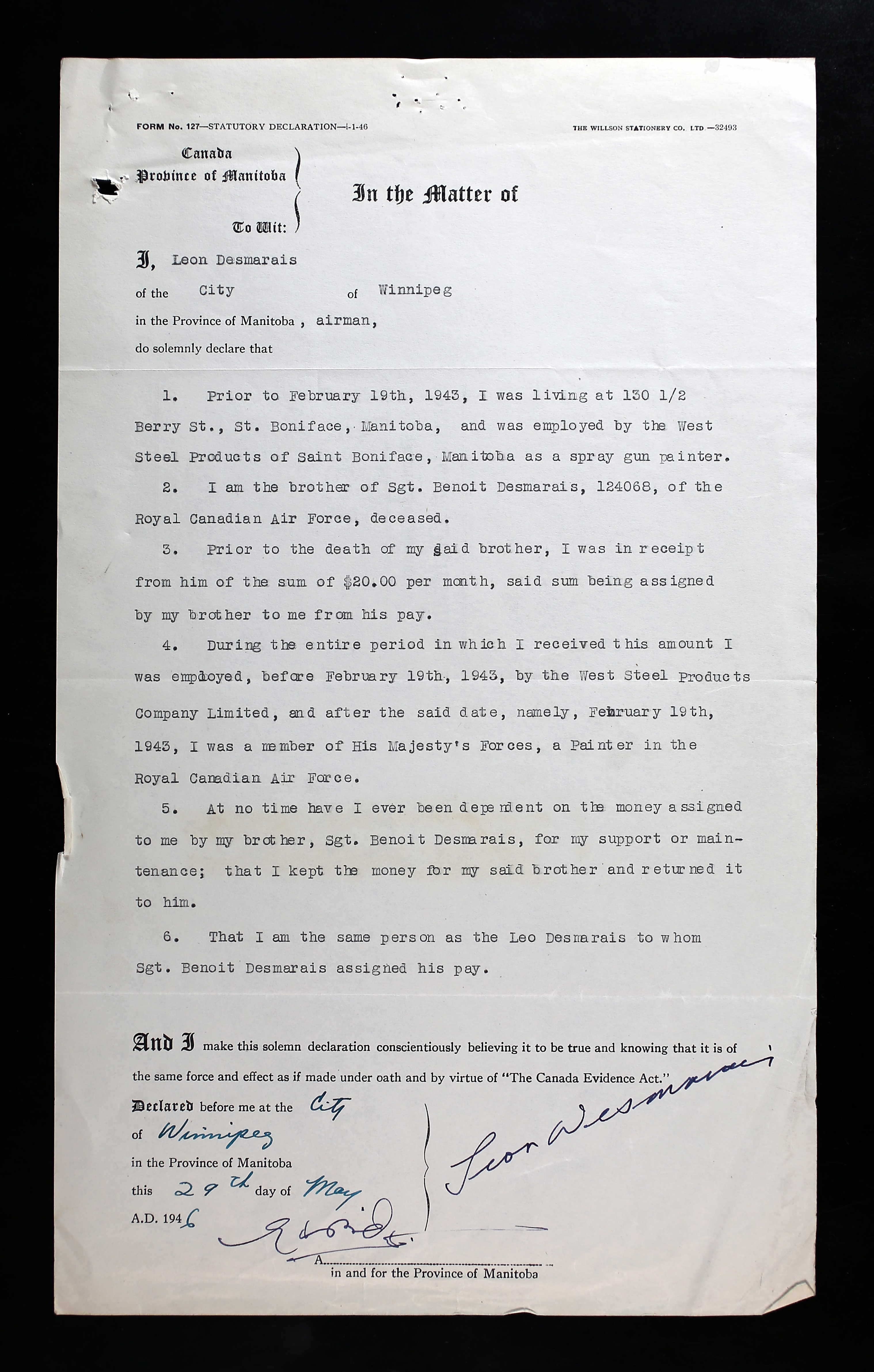

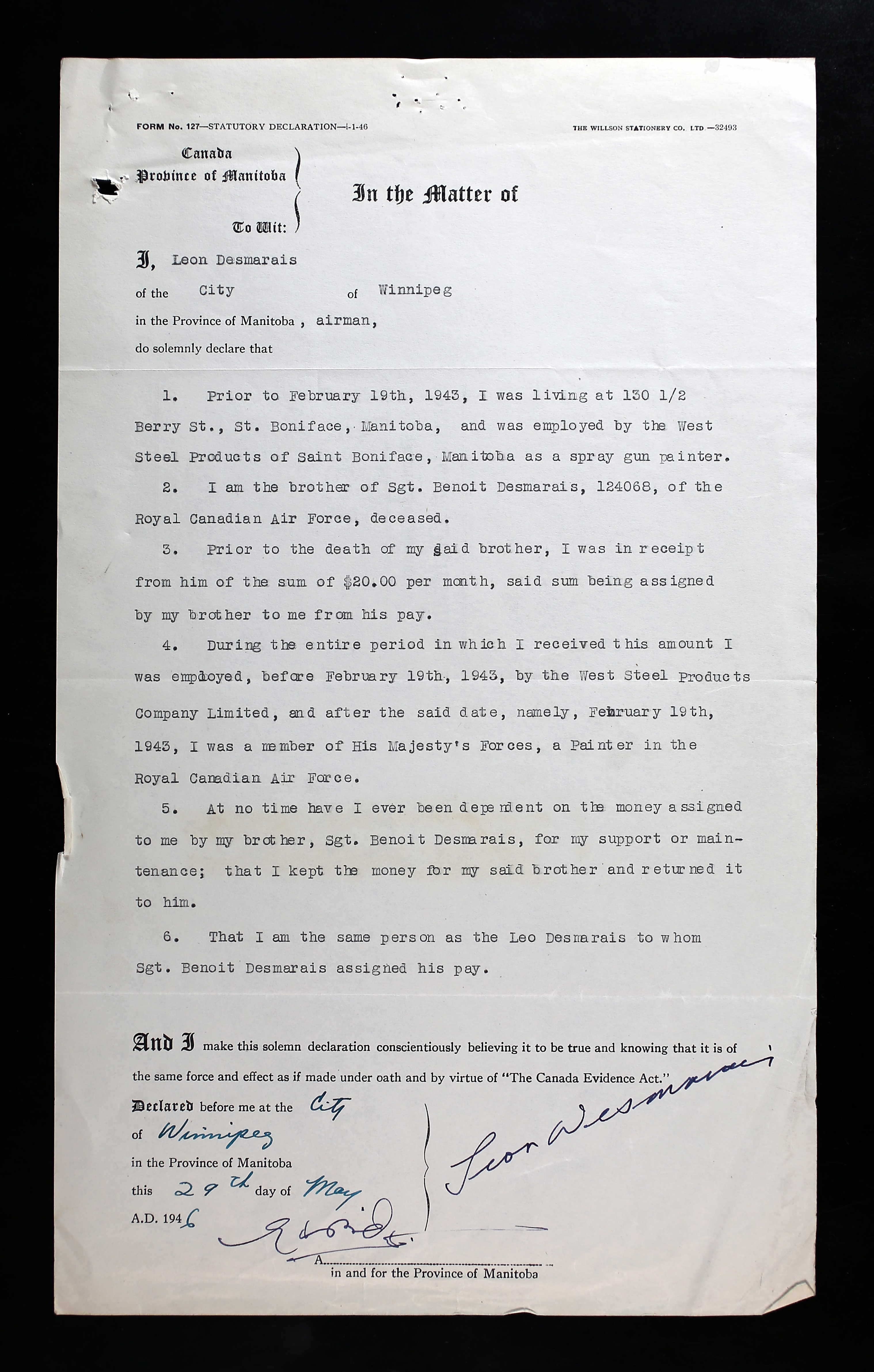

In May 1946, Benoit’s brother, Leo/Leon, indicated that he was in receipt of $20/month from Benoit. “I kept the money for my said brother and returned it to him.” Leo, by February 19, 1943, been working for the RCAF as a painter.

In October 1955, Mr. Desmarais received a letter informing him that since Benoit did not have any known grave, his name would appear on the Ottawa Memorial.