August 12, 1923 - November 5, 1943

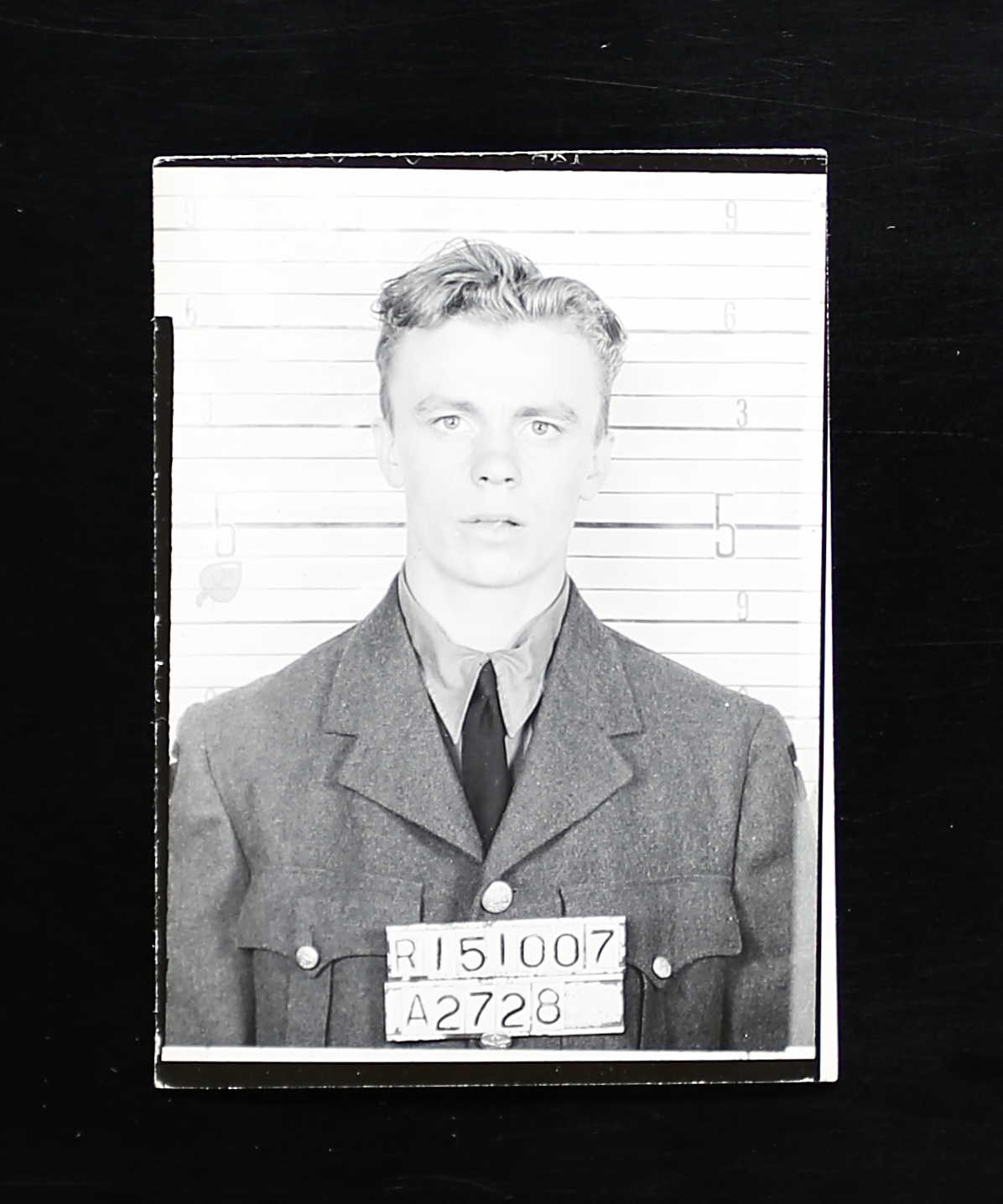

Keith Baines Callaghan was the son of Thomas Michael Callaghan (1878-1958), lumber inspector, and Mabel (nee Baines) Callaghan (1885-1951) of Sudbury, Ontario. He had two older brothers, both in the RCAF overseas: F/L T. C. Callaghan, J13486 and F/O J. W. Callaghan, J35600. He had three sisters: Dorothy Nora Roberts (1913-2000), Phyllis Eleanor Wood (1917-2018), and Alice Marion Schnupp (1927-1997). The family was Roman Catholic. On a statutory declaration dated February 9, 1942, Keith changed the name he was registered at birth from Kieth Linus Baines Callaghan to Keith Baines Callaghan.

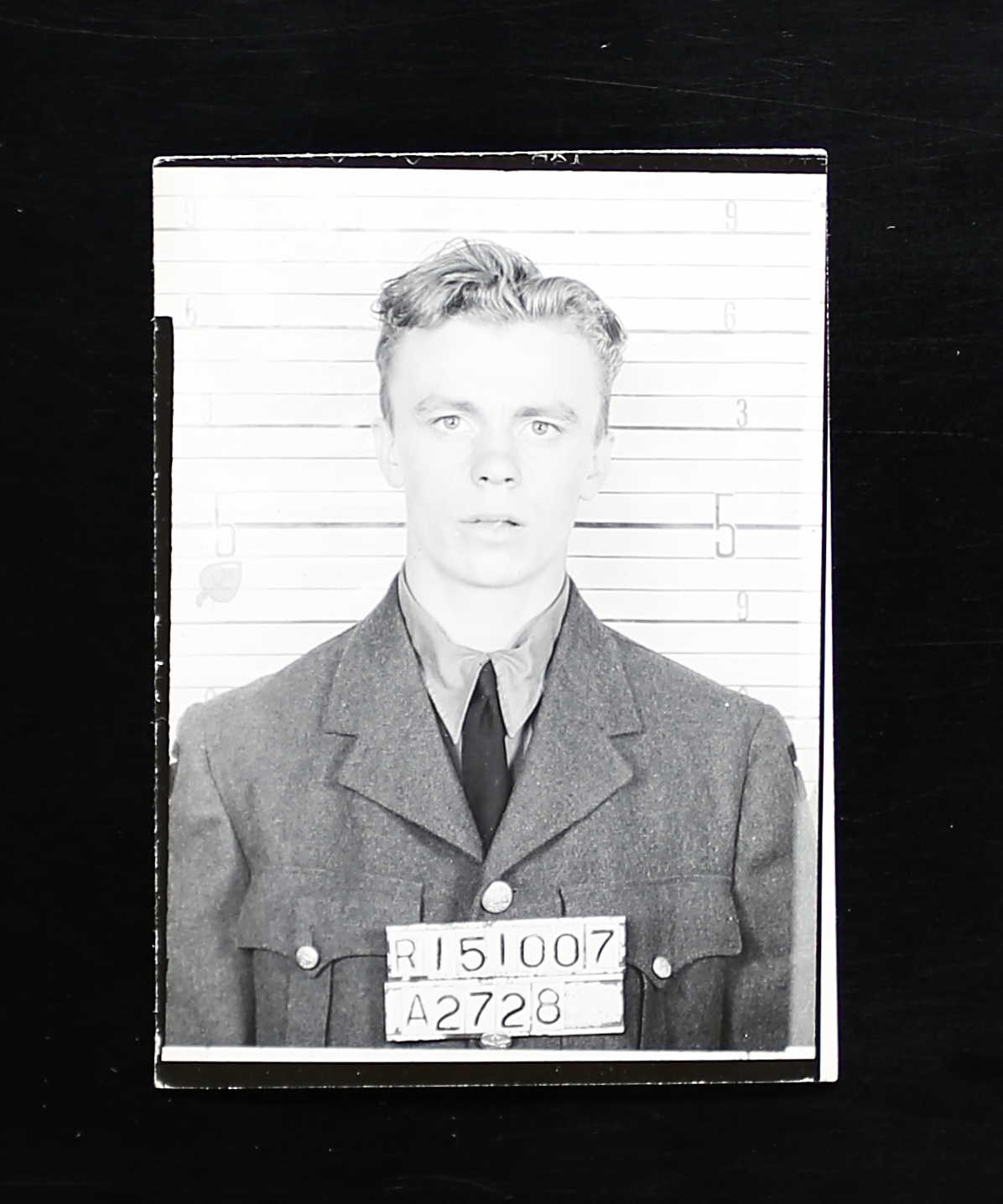

Keith worked at Cochrane Dunlop Hardware as an office boy in 1941 prior to his enlistment in North Bay, Ontario on February 9, 1942. In a reference letter from his high school: “His career in athletics was outstanding as he played on the senior school team in rugby, basketball, and hockey.” He stood 5’7” tall and weighed 116 pounds. He had greenish-hazel eyes, fair hair and had a fair complexion. “Fit, underweight.”

He started his journey through the BCATP at No. 5 Manning Depot, Lachine, Quebec on April 24 to August 1, 1942. He was then sent to No. 13 SFTS in June and July 1942 until he was sent to No. 3 ITS, Victoriaville on August 2, 1942. “Active. Alert and very enthusiastic. Well liked by others in his flight. A good worker and dependable.” Alternative recommendation: Air Navigator.

From there, he went to No. 11 EFTS, Cap de la Madeleine October 25, 1942, until January 9, 1943. “Particularly interested in ground school. Excellent student.” Other comments: “Rather weak in airmanship. Does not use ingenuity and resourcefulness, otherwise an average pilot. Should do well at service school.”

Keith was then sent to No. 1 SFTS, Camp Borden, Ontario January 1 until May 28, 1943. He received his commission May 14, 1943. “A good service pilot all round; inclined to be lackadaisical. Keen about flying.”

He posted to Western Air Command and No. 132 Squadron, Tofino, BC June 3, 1943, then to No. 132 Squadron, Boundary Bay, BC. October 26, 1943: “Keen type. Should make a good fighter pilot with more experience.” S/L G. J. Elliott, RCAF Station Boundary Bay, BC. August 9 to September 5, 1943, Keith was in the station hospital.

He had experience flying the Tiger Moth, Harvard II, and Kittyhawk P40 aircraft.

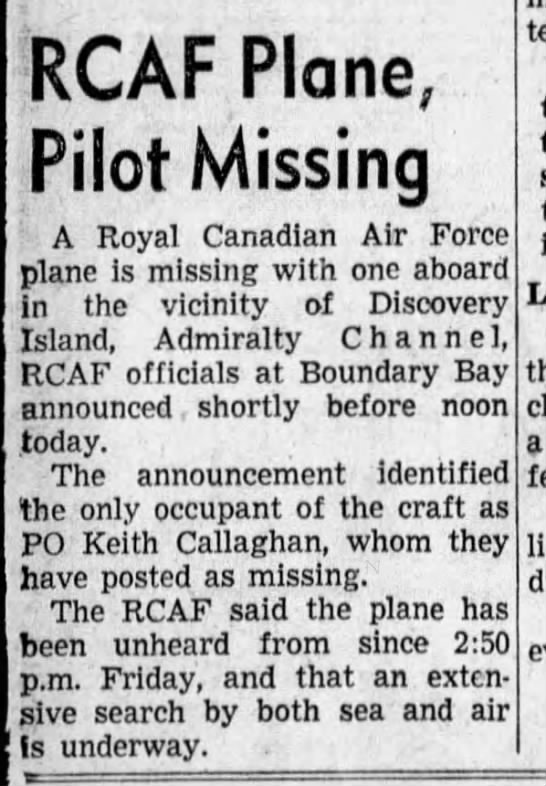

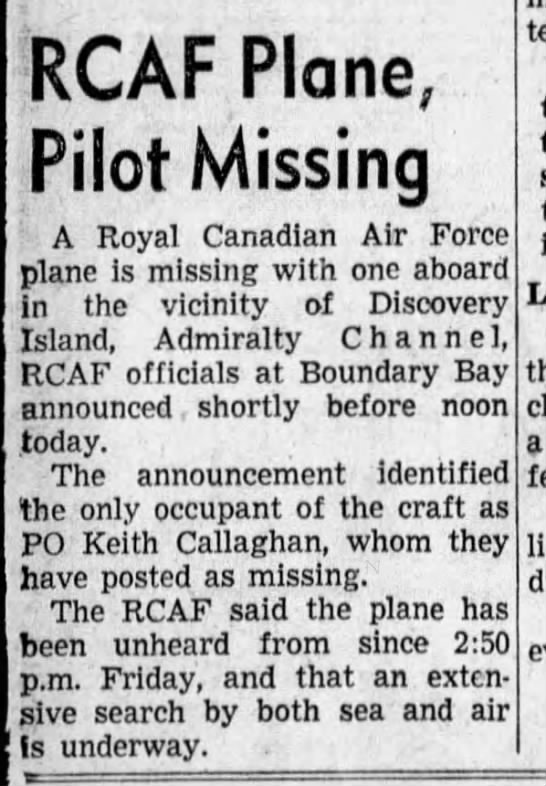

On November 5, 1943, while flying Kittyhawk AK833 near Boundary Bay, BC, he was involved in a mid-air collision with the US Navy Wildcat flown by US Navy Lt. Paul Kermit Donhowe (1917-1943) from Story City, Iowa.

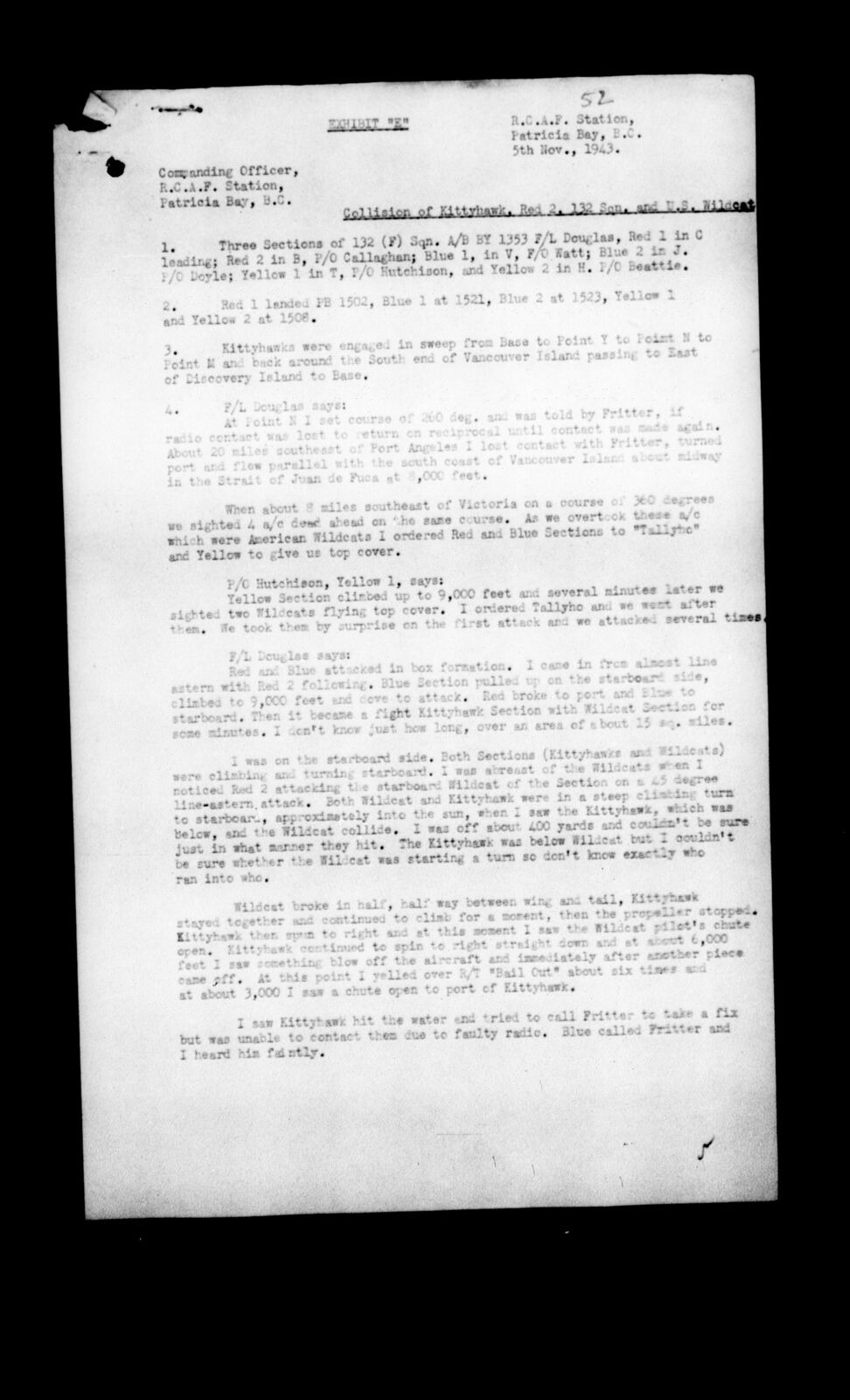

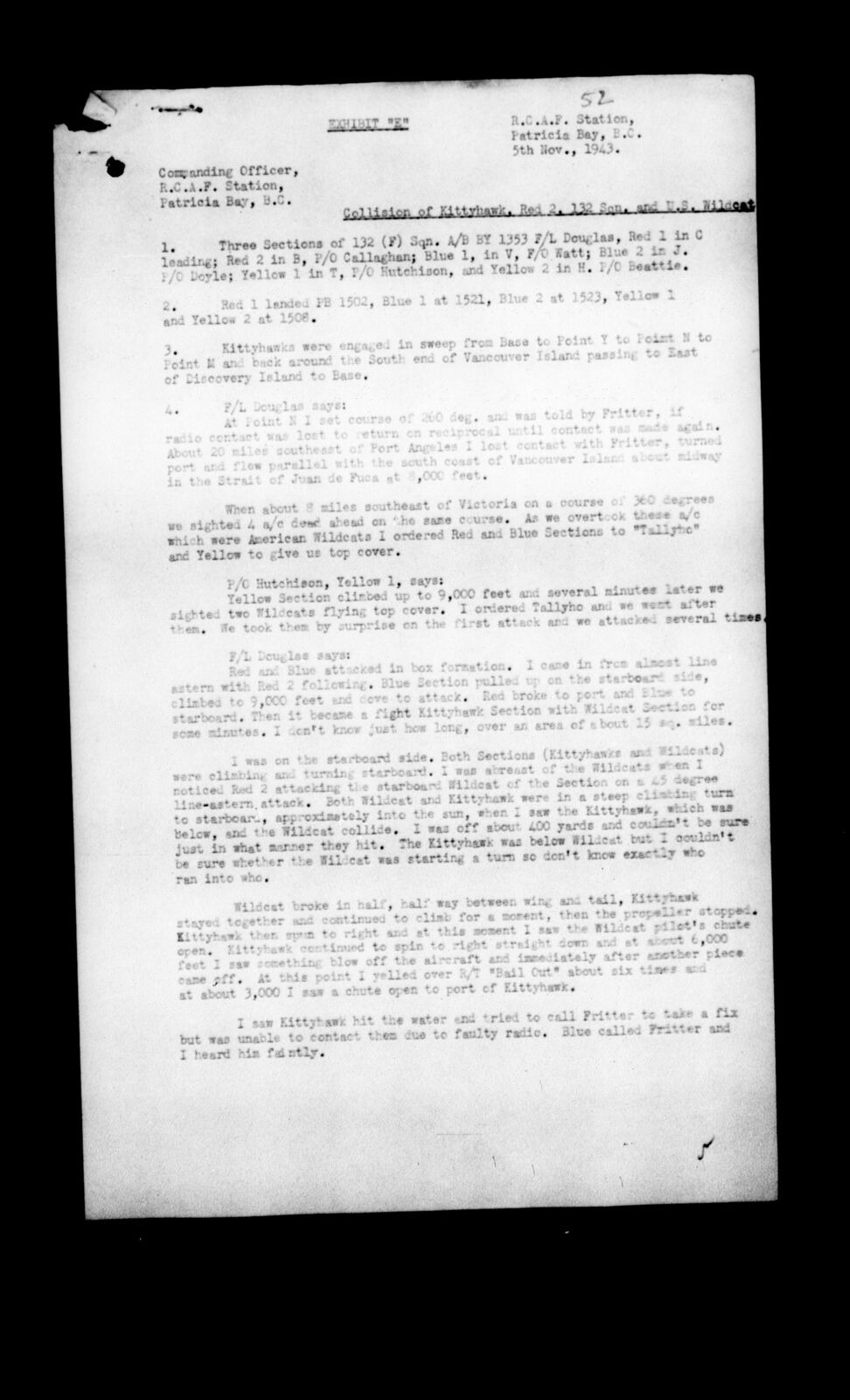

A full court of inquiry was struck. (Microfiche C5934, Image 4195) “F/L Douglas, 132 Squadron, ordered Kittyhawk 833 to fly in a formation of six, fling Red 2, the formation to carry out a sweep from Boundary Bay to Cape Flattery and return. Flight of 132 Squadron attacked a flight of US Navy aircraft and a Canadian Kittyhawk collided with the US Navy Hellcat. Both pilots parachuted into sea and are missing.”

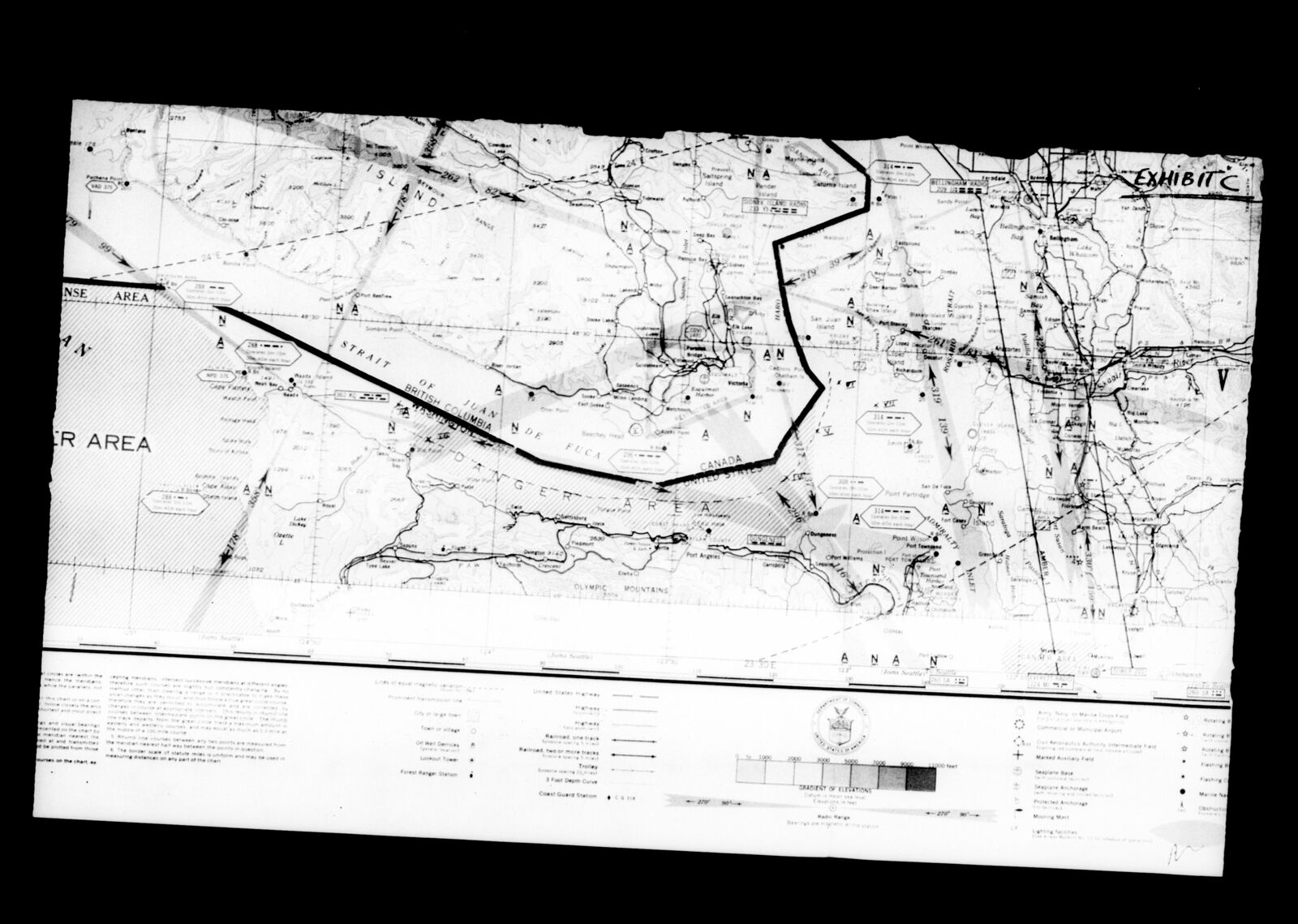

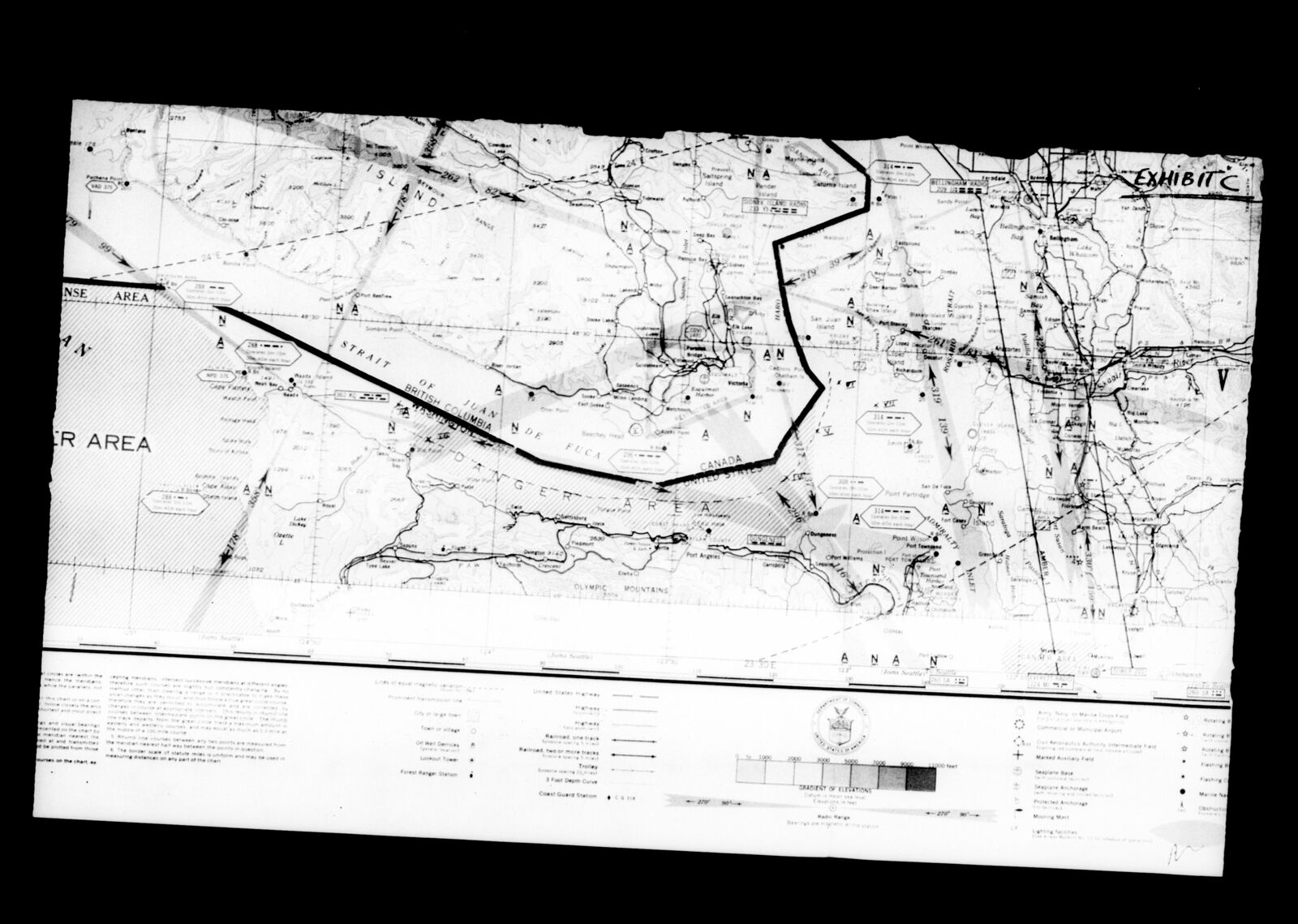

The first witness, F/L W. N. Douglas, J2933, Flight Commander “A” Flight 132 Fighter Squadron, Boundary Bay, stated: “At approximately 1310 hours on 5th November, I asked the Sector Controller at Patricia Bay to arrange an exercise for the Readiness Section. The Sector Controller suggested to me that they go out on a sweep, and I asked that the route take them as far as Cape Flattery and return. At 1313 hours, the Fighter Controller phoned Fighter Controller F/L Sherk, at No. 2 Group, and asked him for the authority on Forms D of the Fighter Sweep covering Boundary Bay, Trial Island to Rocky Point, to Cape Flattery, and return, estimated time of departure 1330 hours, angels eight. Group gave their approval and stated that Forms D would be found through to Sector. Sector Fighter Controller called me, advising that the exercise had been okayed by Group, and at that time I stated that I would like to use two other sections, Yellow and Blue, on the exercise in addition to Red Section (Readiness). At that time, the Sector Controller requested that I make arrangements for another Section to stand in for Readiness Section in the event that Readiness Section would not land within an hour. The Sector Controller also mentioned to me that the aircraft were to identify all aircraft in the vicinity of their sweep, but there was to be no dog fighting. I stated there would be a slight delay in getting the other two Sections ready to take off, and that the estimated time of departure would be slightly later. The Sector Controller then phoned Group and advised the Fighter Controller there that 132 (F) Squadron wished to take Red, Yellow and Blue Sections on the exercise. At 1325 hours, Group phoned through to Sector Form D, Serial No 1. A Fighter Sweep, otherwise known as ‘rodeo’ is one of the number of types of exercises which are carried out as a regular training schedule of the Fighter Squadrons under control of Patricia Bay Sector. A sweep for training purposes is to cover a certain area and identify all aircraft within that area. At 1353, Kittyhawk C for Charlie and B for Baker, Red Section, Pilots P/O Callaghan and I, Kittyhawks V for Victor and J for Jig, Blue Section, Pilots F/O Watt and P/O Doyle, and Kittyhawks T for Tare and H for How, Yellow Section, Pilots P/O Hutchinson and P/O Beatty, were airborne on the exercise. From there on, instructions given by Deputy Controller, Sgt. Paterson, to 132 Squadron aircraft and contained in the copies of the monitor’s log which is marked Exhibit ‘B’. In this log, the R/T name of 132 squadron is Zito. As the aircraft were rounding Victoria, the Controller asked the Deputy Controller to advise the Zito Red leader (me) if R/T contact between Zito Red Leader and Fritter, which is the R/T call sign of Patricia Bay Sector, was lost, we were to fly a reciprocal vector until R/T contact was again established. It will be noted from the copy of the monitor’s log that the Zito aircraft were given a 0, which is a position fixing procedure, soon after they were airborne. It will also be noted that at 1430 hours, the Deputy attempted to contact Zito flight and check their position as the first plots showed that the aircraft had not continued on their vector to Cape Flattery and were returned to on the reciprocal. By the time I had reached Victoria, I had found it necessary to have Blue Section Leader pass two or three R/T messages for me as my radio contact was poor. After passing south of Victoria, I crossed near Church Point, marked “I” on the attached map, Exhibit “C.” At that time I received a vector of 260 degrees which I turned onto. When we reached point marked “II,” approximately on the US/Canadian border, I tried to talk to Fritter, so I turned to port and returning towards base along a path about four miles out to sea from the American coast along the dotted line, marked “III,” on Exhibit “C.” At about 1433 hours, when we were on a point marked “IV,” I sighted four aircraft ahead of me about 300 feet below traveling in the same direction as my formation.

“I ordered Yellow Section to remain as top cover and led Red and Blue Sections in a mock attack on these aircraft. This mock attack was delivered from the stern chase position. I did not alter course to make the attack from a shallow dive. I opened up my throttle to increase my speed to 250 mph. I ordered the attack by radio. I indicated the position of the target aircraft to my flight and by radio indicated that the attack was to be made. My position is marked at point “V.” The formation at this time was that there were two aircraft about 1500 feet above myself and Red and Blue Sections were flying aircraft abreast…the aircraft being about 300 yards apart, and the sections about 250 yards apart. At about 150 yards did I press my own attack. There were two Sections of two aircraft each, flying in close echelon formation. The target aircraft that we attacked was the one on the extreme port. I did not see any other of my pilots make their attacks.

“After making my attack, I pulled up and to port. I saw the target aircraft alter formation. After I passed beyond and above the port target section of the aircraft, I saw those two aircraft also pull up and to the left. These aircraft appeared to be following me. I identified the target aircraft after my attack on a Grumman Wildcat. I did not know they were aircraft of the US Navy before I made my attack. At the time of this attack, I was one mile one way or the other on the Canadian or American side of the border. I am not sure. I had pulled left and above the Wildcats with overtaking speed. I then saw the Wildcats about 300 yards to port. They appeared to turn towards me and I turned to starboard so as to be turning in the same direction as they were. Due to the superior climb of the Wildcat, I next observed the two Wildcats slightly above and outside of my turning radius. I saw a P.40 go by my port side in a climbing turn and collide with one of the Wildcats. I saw the P .40 bounce away from the Wildcat, continuing to climb with the propeller of the P.40 stopping and then I observed the Wildcat breaking up. As the Wildcat broke apart, I observed a parachute open near it. I am not certain at what altitude that the parachute appeared but approximately 8500 feet. The P.40 continued to climb, stall, and spin to the right. I watched the aircraft spin about 1000 feet and then by radio told the pilot to bail out several times. I kept repeating this and eventually I saw the pilot bail out, his parachute open at approximately 3000 feet. I was still at about 8500 feet when I saw the Kittyhawk pilot bailout. I also observed two pieces flying off the P.40, one believed to be the cockpit hood. I watched the parachutes descending for a while. I watched one of them go down into the sea. That would have been the Kittyhawk pilot. There was of course a considerable difference in height between the two parachutes in the air, however they were quite close together. In fact, one appeared to be almost directly above the other. I endeavored to watch the parachute in the water, but due to the high seas which were running, I lost sight of it almost immediately. I did see the Wildcat parachute again and it was then some distance downwind. I was about 2500 feet when I saw the first parachute strike the water, and then I continued diving to sea level, but I could see no trace of the pilot or parachute. I did not see the second parachute hit the water. I saw the Kitty Hawk dive in the water and was immediately lost to sight. It threw up quite a column of water. I could not estimate the distance between the Kittyhawk and the parachute entering the water. I saw an oil slick after five or 10 minutes, but I could not say which aircraft had caused it. The oil slick was definitely upwind from the pilots. Where the parachutes hit the water it is marked “VI."

“I did not bother about the other pilots. I endeavored to obtain a radio position fix. With regards to this, I was unable to contact Fritter. However, Blue Leader heard my requests for fix, and he contacted Fritter for me. I did not give any orders to the other Kittyhawks to assist in the air-sea rescue of these pilots because all the aircraft in the vicinity were orbiting the position. At 1450 hours, 15 minutes later, I picked up radio messages indicating that Blue Section had been instructed to remain in the vicinity of the collision and for the remainder of the aircraft to land at Patricia Bay. I, therefore, returned to Patricia Bay at approximately that time, landing there.

“When I ordered the contact to be made, I said, ‘Four Boggies, twelve o’clock. Zito Red and Blue Sections attack. Zito Yellow Section take top cover.’ This was pre-arranged because we were carrying out an authorized sweep which included identifying any aircraft which were sighted. It was not necessary to approach the Wildcat aircraft as closely as we did to identify them. When I attacked the Boggies, they were unidentified aircraft, and I wanted to make absolutely sure that they had no advantage on me in the event of their being enemy aircraft. I first realized that these were aircraft of the United States after my first run. It is not common practice in my squadron for my fighter aircraft to attack and so approach closely strange aircraft in the air.

“I have been Flight Commander of 132 Squadron for five months. Previous to which I was a flying instructor at a Service Flying Training School. I have 180 hours flying time on the Kittyhawk. I have had instruction on leading other aircraft in such attacks as this flying as a number two man for some time. It has been drawn to my attention that a flight leader is responsible for ensuring that other members of the flight are not led into dangerous positions in the air. Depending on the type of aircraft I could be attacking, I have been instructed to break away a flight after doing a stern attack on other aircraft. It is not usual to break away down and to one side rather than pull up because that would give other fighters the advantage of height, especially in the case of equal numbers of enemy aircraft. Depending on the circumstances, you might break either up or down.

“P/O Callaghan was probably not carrying a parachute dinghy because his dinghy was in his locker after the accident. I was wearing one myself. P/O Callaghan had been instructed as a number two man to follow his leader at all times; however he was not following me as he should have been when he collided with the Wildcat. It is an order in our Squadron that pilots carry dinghies. He was wearing a Mae West. He was with 132 Squadron about 5 1/2 months. He was wearing a U.S. Navy type life jacket. I was not aware that they might fail when used with the CO2 bottles to inflate them because they are too short. I saw a freighter coming out of Admiralty Inlet just as I was leaving the area. It was about 20 miles from the position of the pilots in the water.”

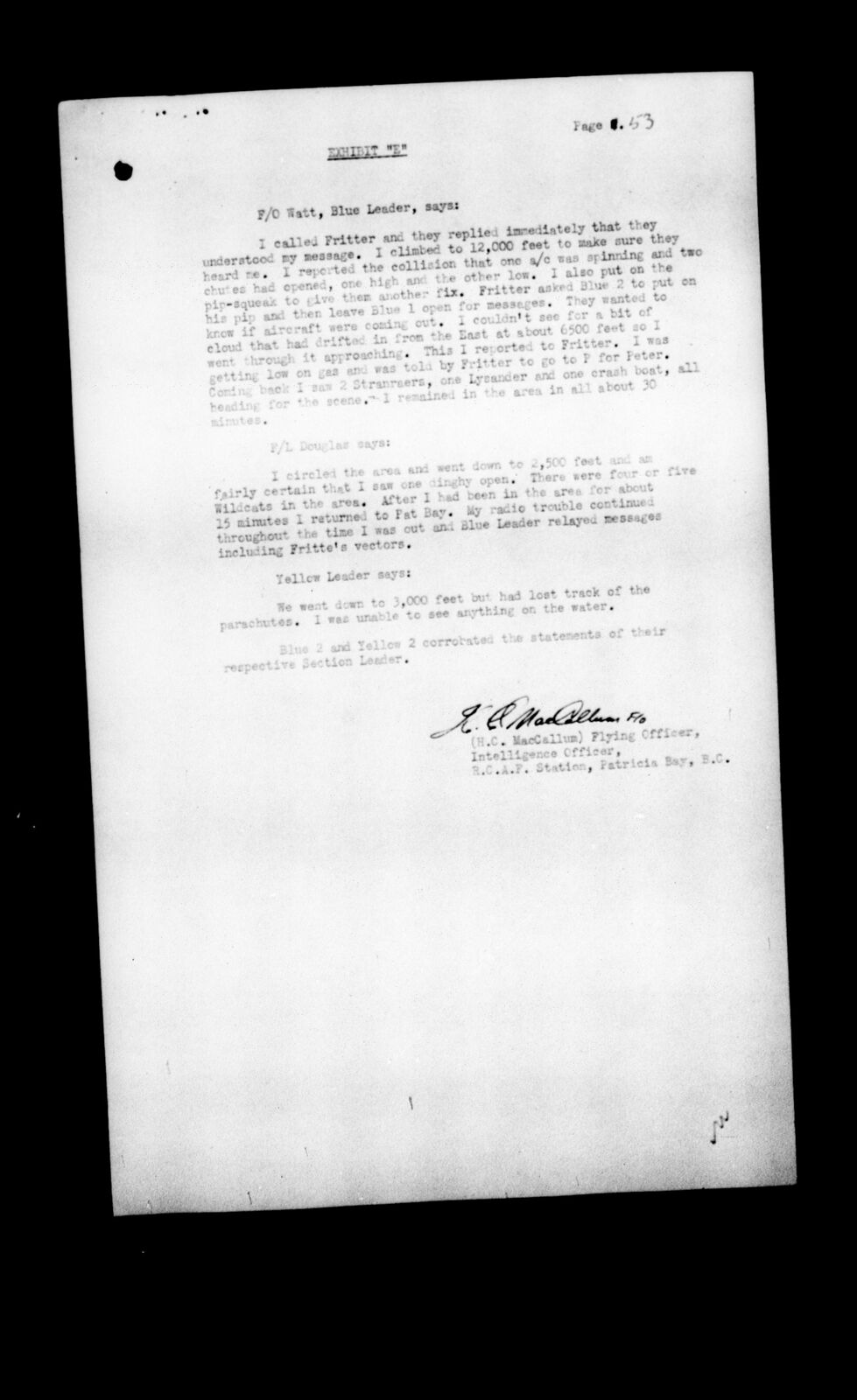

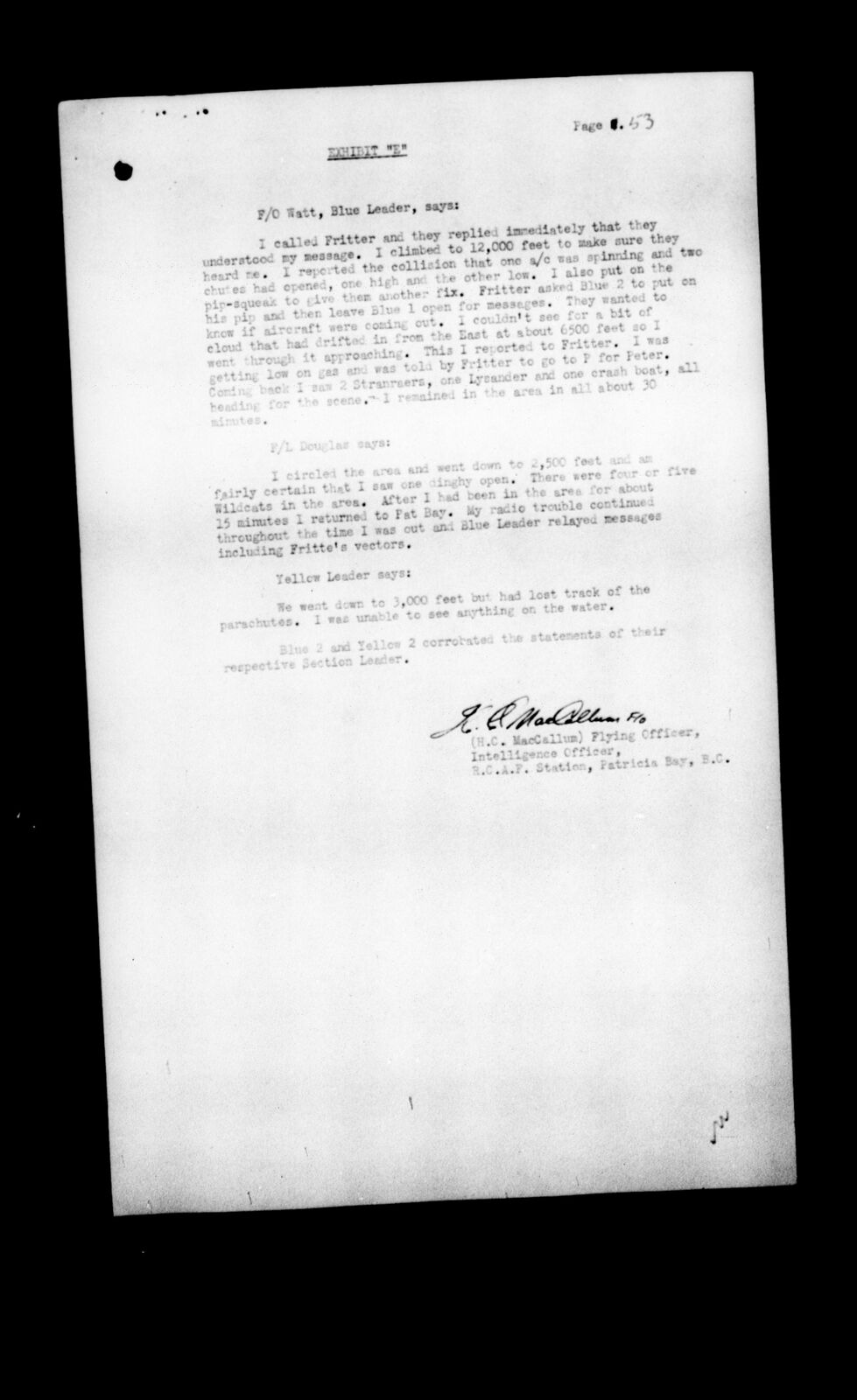

The second witness, F/O T. R. Watt, J10399, pilot, stated that he was in a flight from Boundary Bay on November 5th which resulted in an air collision between an aircraft of his flight and a Wildcat. “I was flying Kittyhawk 844, V for Victor, and I was leading Blue Section. We were about 10 miles off the American coast. I had sight of a flight of American Wildcats when Red Leader said, ‘Four Boggies twelve o’clock.’ I was given an order to carry out an attack on their aircraft. The Wildcats were about 700 yards away. My altitude was at about 8500 feet. They were about 500 feet below and ahead of us. My Section in relation to the Red Section we were starboard slightly behind and slightly above. I followed Red Section in a stern quarter closing by the stern attack. My number two was by the stern on me. No aircraft were carrying camera guns. After the attack, I turned to starboard and continued approximately at the same altitude passing below the Wildcats which were then climbing. I saw Red 2 make an attack and break off to port. I did not see him collide with the Wildcat. He was following Red 1 more or less when I saw him break off his attack. I knew there had been an air collision because a few seconds after the attack I heard, ‘Bail out!’ repeated over the radio. I saw one parachute immediately. Later I saw a second parachute. I did not follow the parachutes down. I heard Red Leader calling for a radio fix in vain, and I took over the radio call and climbed for altitude to be sure of getting a radial fix. I left the scene of the accident at 1515 hours while I was returning to Patricia Bay to land.

“I had been instructed in the proper manner of delivering an attack on another aircraft. Yes, I know that it is forbidden to carry out fighting tactics without prior arrangement. No, I did not think I was breaking flying regulations at the time that we closed in on the Wildcats. I understood we were to attack aircraft on the mission we were on. Some of the pilots in 132 Squadron wear US Army pattern Mae West's. I did not see what type P/O Callaghan was wearing. Yes, I was carrying a dinghy.”

The third witness, F/L L. F. P. Williams, C6881, Flying Control Officer: “The aircraft in a flight led by Flight Lieutenant Douglas in the afternoon of November the 5th was under the control of Boundary Bay for takeoff only and were handed over to Sector Control soon after they were airborne. The rules regarding fighter aircraft approaching other aircraft in the air is forbidden. Not to my knowledge are fighter aircraft in the habit of approaching other aircraft in the air for purpose of fighter attacks without previous arrangement regarding specific aircraft.”

The fourth witness, P/O W. J. Hutchinson, pilot 132 Squadron: “We were quite close to the coast. I did not take part in a mock attack against four American Wildcats. I did not see Red and Blue Sections in such an attack because I was ordered to climb up as top cover and in doing so, encountered two more Wildcats at approximately 9000 feet which I presumed to be top cover for the other Wildcats and against which I led my section into mock attacks. I did not see an air collision. The first indication I had was a radio message telling me not to transmit as there had been a collision. I did not see either parachute nor airplane enter the water. After I heard there had been an air collision, I circled, looking for signs of an accident or the remaining aircraft and when I located the latter, I orbited from 8000 feet to 3000 feet to help locate the pilots of the crashed aircraft, neither of which I saw. I continued in the search until ordered to land at Patricia Bay. No, I was not carrying a dinghy. I believe most of the pilots fly with dinghies. I am aware that some CO2 bottles are too short to be successful with the US Navy Mae Wests because some weeks ago someone whom I do not remember brought some washers to the Squadron to make the short bottles fit in the socket of the Mae West. I know that there are air-sea rescue facilities in this area. There are Lysanders at Patricia Bay at readiness. The only surface craft I know is of a boat that is in the bombing area when we are carrying out exercises. I do not know of instructions and information passed out by Western Air Command concerning the air-sea rescue, although I have read the pilot's orders.”

The fifth witness, P/O Lawrence Francis Doyle, J27212, pilot, 132 Squadron: “I was flying in the formation as Blue 2 in Kittyhawk P.40 J for Jig. I was flying wide on my leader and was somewhere near the middle of the channel on the port side of Red Section. I saw four Wildcats. I guessed they were Wildcats. I was about 300 yards before I made this possible identification. I followed my leader in a stern attack. We were overtaking them at no great speed. I was about 8500 feet in relation to the Wildcats when we began our attack; they were at 500 feet below. I did not see an air collision. The first I heard that there had been an air collision I heard, ‘Bail out’ over the R/T. I saw one spinning aircraft and one parachute. The parachute entered the water after the aircraft, and I believe 300 yards distance from it. I was not carrying a dinghy. I am in the habit of carrying one. I was not carrying one on November 5th because it had been recalled for repairs by the parachute section. It is customary to wear dinghies. I lost sight of the parachute in the water almost immediately. I was about 4000 feet high. I did not follow the parachute to sea level because my leader had climbed up and I knew that the radio would not work at sea level. I saw one surface vessel to the southeast which I could not positively identify. When I left the scene, he was about 1/2 mile. I did not try to get his attention because there were several Grumman Wildcats at sea level near the ship, and I presumed that they would carry out the necessary search. I was airborne for about 1 1/2 hours. I was the last to land. The insurance of the Kitty Hawk under which conditions I was flying is about two hours safe. The matter about the CO2 bottles that will not operate with the US Navy jacket has been discussed in the Squadron, and Pilot Officer Callaghan had the proper bottles as I helped him to put them in three days previously. The US Navy jacket has no buoyant material, but it has means of oral inflation other than the CO2 bottles.”

The sixth witness, P/O Donald Bernard Beattie, J29164, pilot 132 Squadron: “I was flying Kittyhawk H for How and my position was Yellow 2. The first indication I had that there was a collision was hearing it mentioned on the R/T. We were not involved in dog fighting with Wildcats. We were not close enough to dog fight, but I was following Yellow One and we went after two. These two Wildcats were above the main formation of the aircraft where the collision occurred. I was not wearing a dinghy. I was intending to have my parachute exchanged and I had put off carrying a dinghy for a week or so.”

The seventh witness, Cpl Kenneth Lester Bishop, parachute rigger, 132 Squadron: “There are 40 seat-type parachutes in 132 Squadron. There are 38 K-type dinghies in the squadron. I think the last time Pilot Officer Callaghan’s parachute was inspected was October 19th. The dinghies are inspected each time the parachute is inspected which is once a month. The pilots put them on themselves. The pilots retain the cushions from where the parachutes have dinghies. The parachutes customarily are attached to them. One parachute per pilot is out on loan in the Squadron. I have issued 7 dinghies to the pilots, and Squadron Stores have issued some, and I believe there is one to each pilot.”

The eighth witness, Flight Sergeant Kenneth William Loud, 4096, aero-engine mechanic 132 Squadron stated that Kittyhawk 833 was fully serviceable.

The ninth witness, LAC William MacKinnon Ford, wireless mechanic stated that the radio aboard Kittyhawk 833 was working normally.

The eleventh witness, F/L Martin John Bishop Hennessy, C7051, Senior Flying Control Officer at Patricia Bay stated that his air-sea rescue aircraft did not sight any RCAF Kittyhawks at the scene, but sighted Grumman Hellcats. “A search of the whole area was ordered about 1600 hours. Three Stranraer, one Ventura, two Lysanders with additional Venturas ordered off, but it was then too late in the day. One Air-Sea rescue vessel available at Patricia Bay was despatched immediately…. there were five marine craft on search. The condition of the sea was very rough.”

The 12th witness, F/O Malcolm MacMurray Hay, staff instructor at No. 3 O.T.U., Patricia Bay stated that aboard Stranraer 913, “I proceeded immediately to five miles northwest of Gordon Head to investigate the area. A Lysander was flying in this immediate area…I proceeded eight miles due east of Discovery Island after receiving R/T instructions from Control Tower. On arriving at that location, we searched the immediate area very carefully in from there carried on a series of parallel searches. After thoroughly investigating the area, I carried two series of parallel searches which effectively swept the whole area south of San Juan Island. I did not see any oil slicks on the water. I was searching at between 200 and 300 feet. The condition of the sea was such that the wind was blowing from a southwest at approximately 20 knots and gusty. There were heavy seas running in the area east of Discovery Island. The seas were approximately 10 to 15 feet high. It would hinder visibility due to the breaking seas. The weather conditions at the time were such that visibility of such a nature in no way would hinder the search.”

Additional pilots gave similar statements as F/O Hay above.

Exhibit “D” showed that Pilot’s Order No. 54 dated June 19, 1943: “Pilots will wear dinghies at all times and ensure they have something to puncture them with in case of accidental inflation in the A/C.”

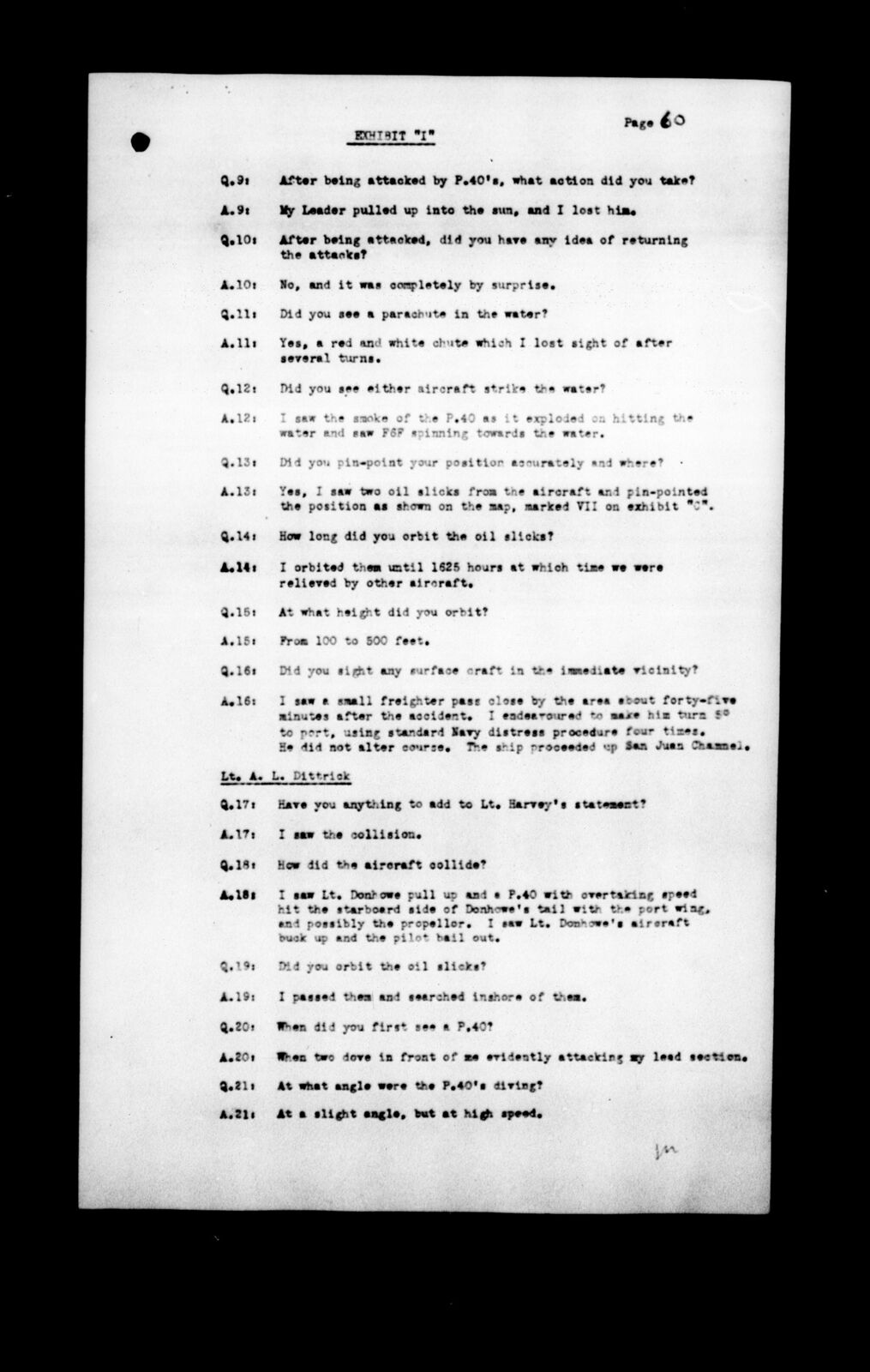

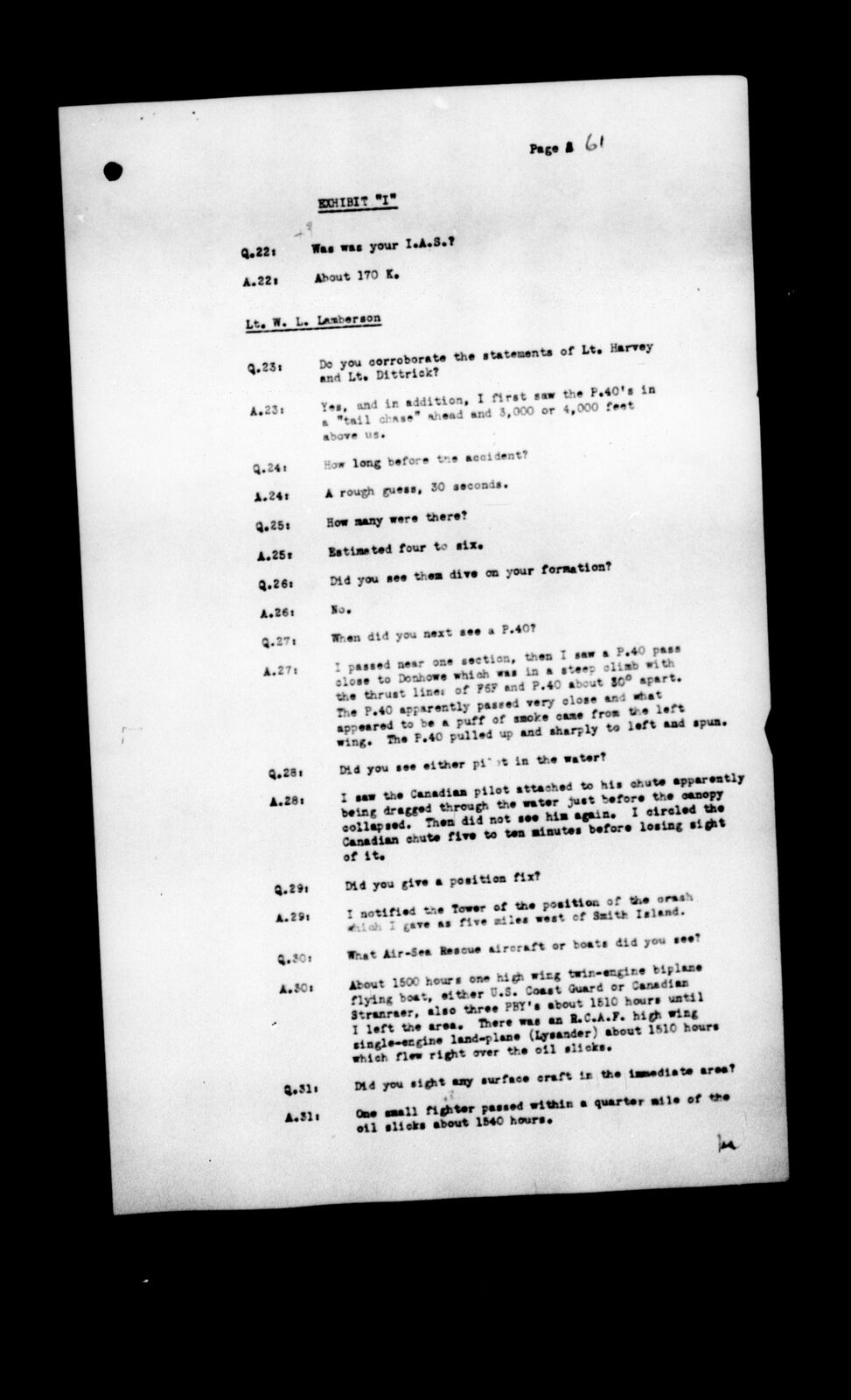

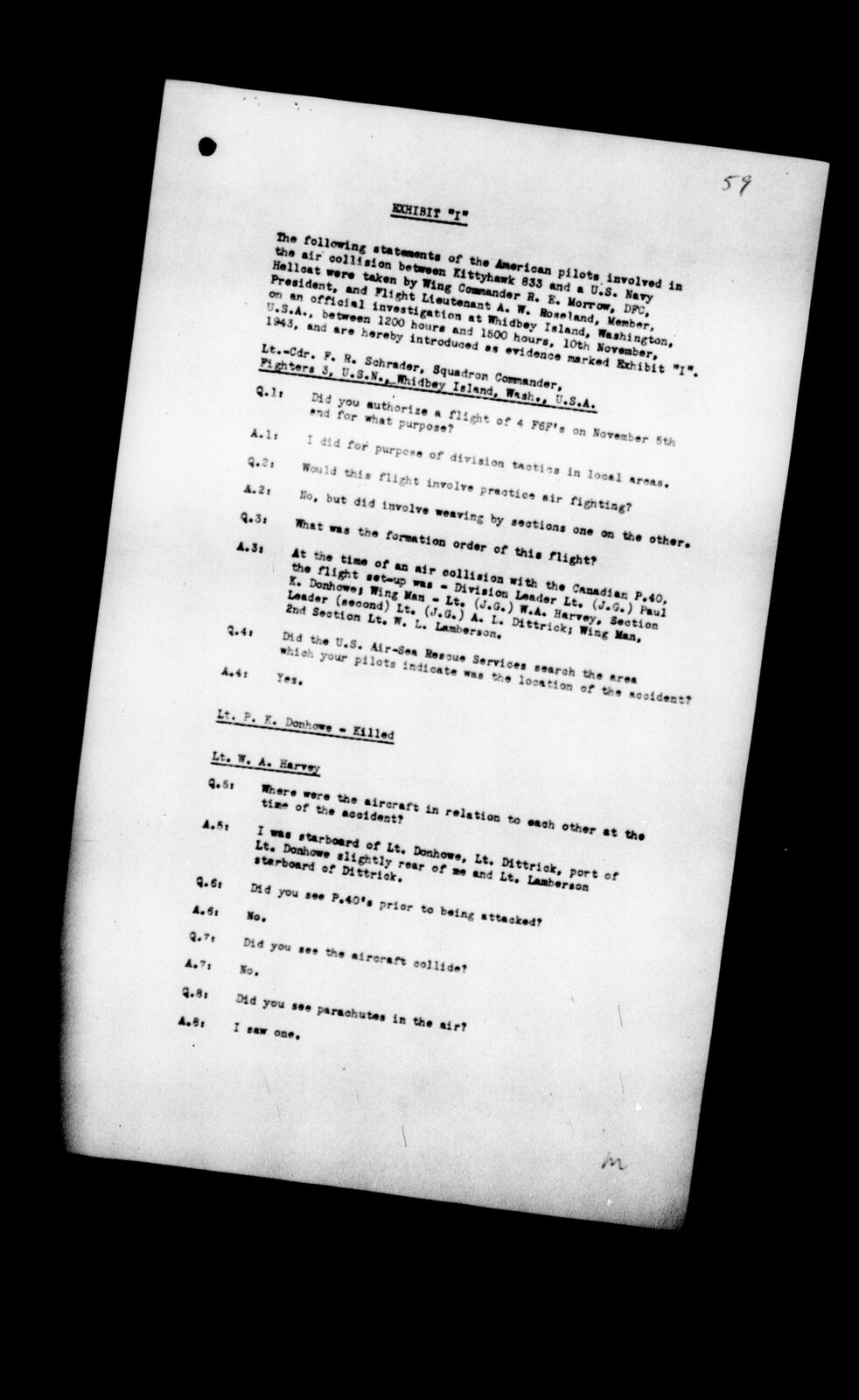

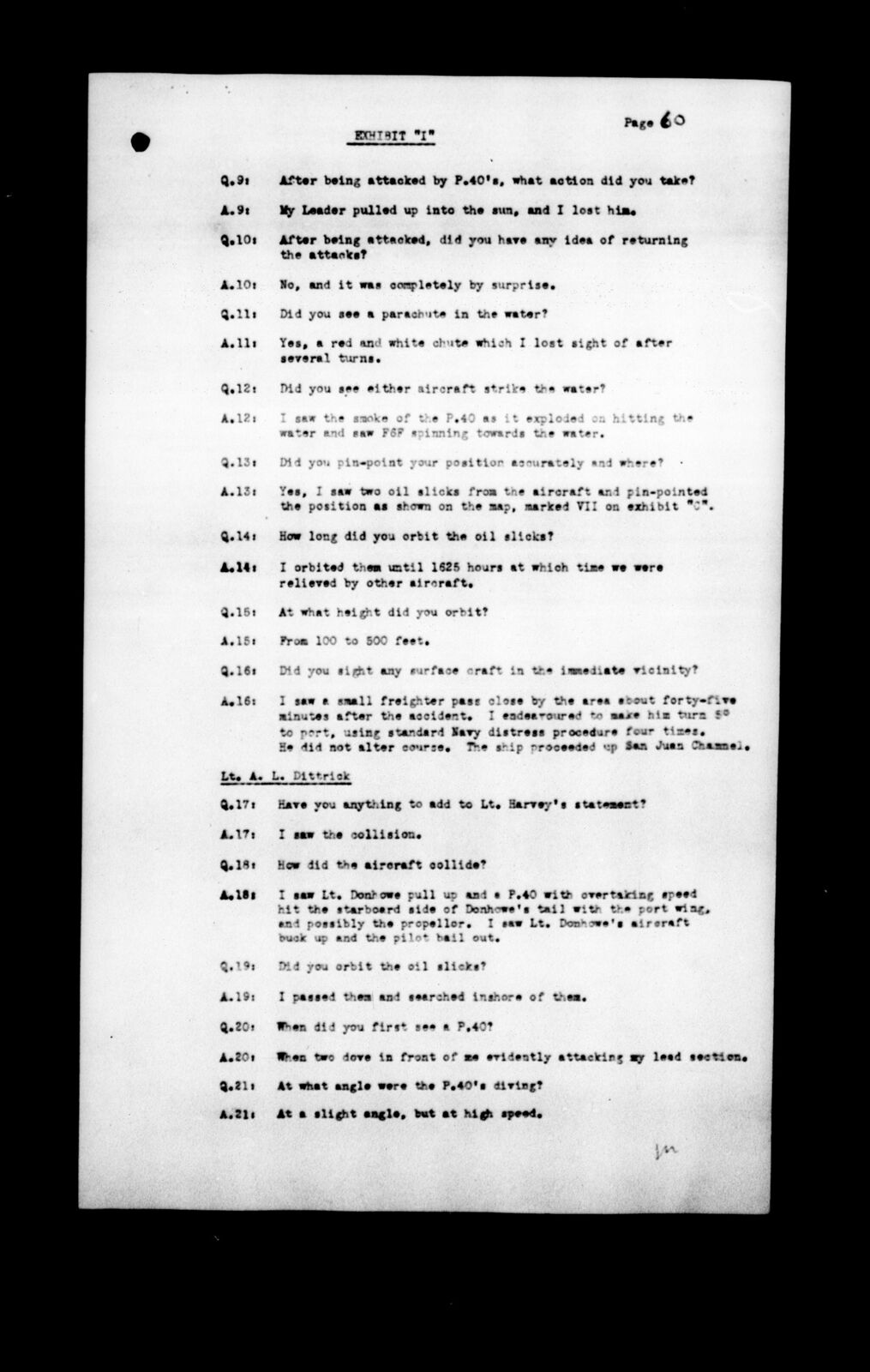

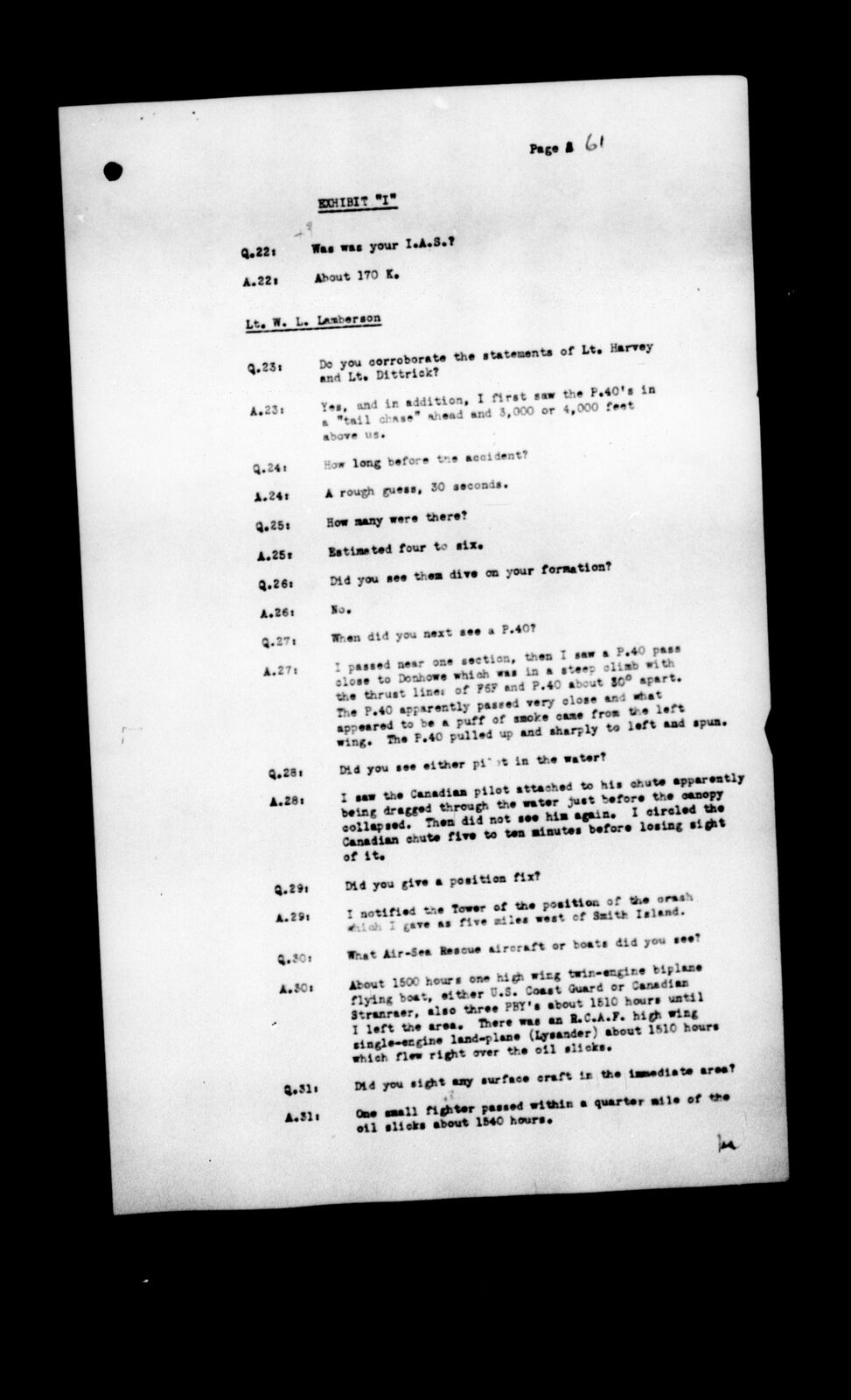

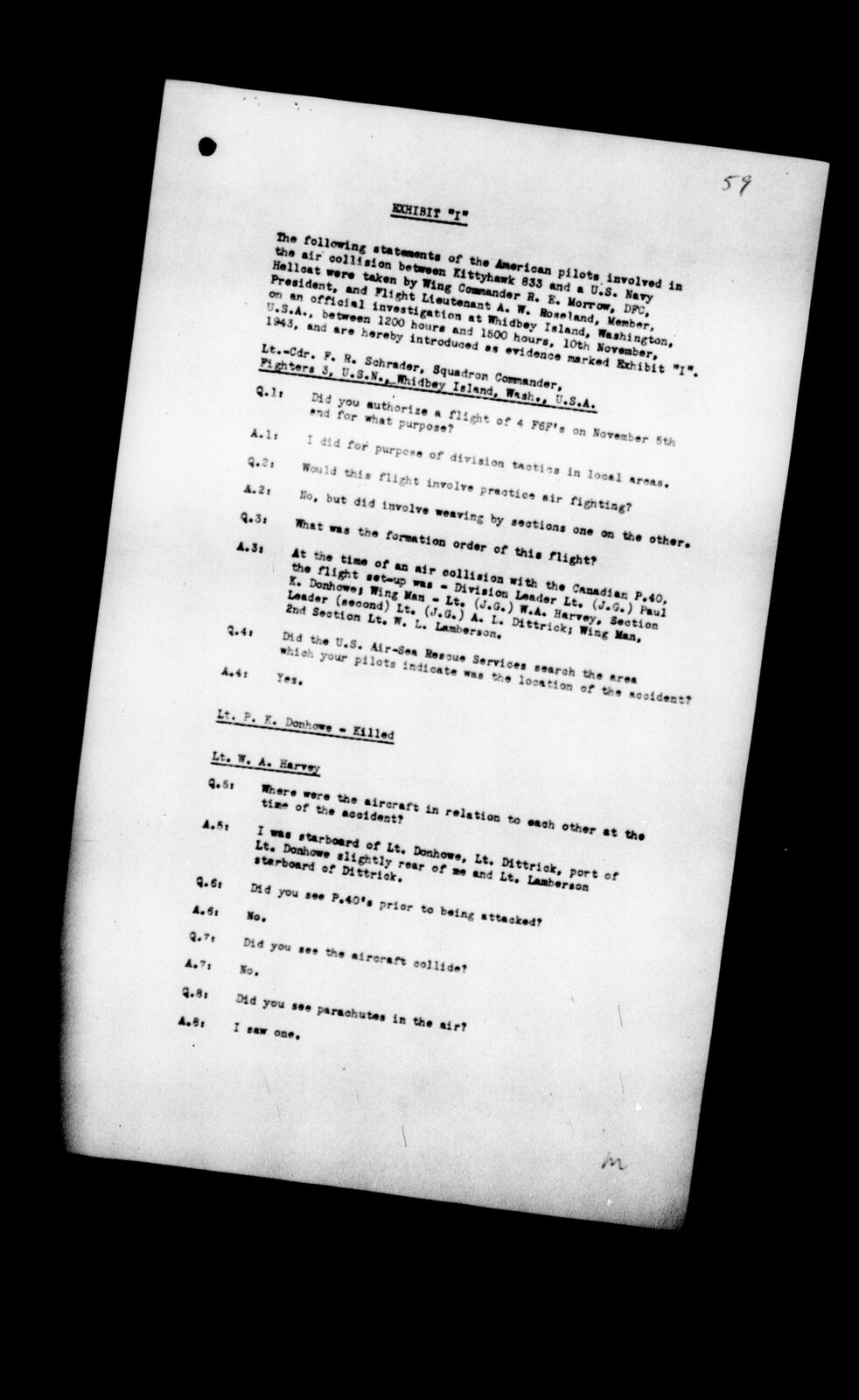

The American pilots involved in the air collision between Kittyhawk 933 and the US Navy Hellcat were interviewed on Whidby Island, Washington on November 10, 1943 for three hours. [See documents above.] They stated that they were completely taken by surprise. One pilot saw the smoke of the P.40 as it exploded on hitting the water and saw [Hellcat] F6F spinning towards the water, seeing two oil slicks. Another pilot saw the collision. “I saw Lt. Donhowe pull up and a P.40 with overtaking speed hit the starboard side of Donhowe’s tail with the port wing, and possibly the propeller. I saw Lt. Donhowe’s aircraft buck up and the pilot bail out.” A third pilot stated, “I saw the Canadian pilot attached to his chute apparently being dragged through the water just before the canopy collapsed. Then I did not see him again. I circled the Canadian chute for five to ten minutes before losing sight of it.”

During the investigation, there was no evidence or mention of the flying ability of F/O Callaghan nor of the weather conditions at the time of the collision.

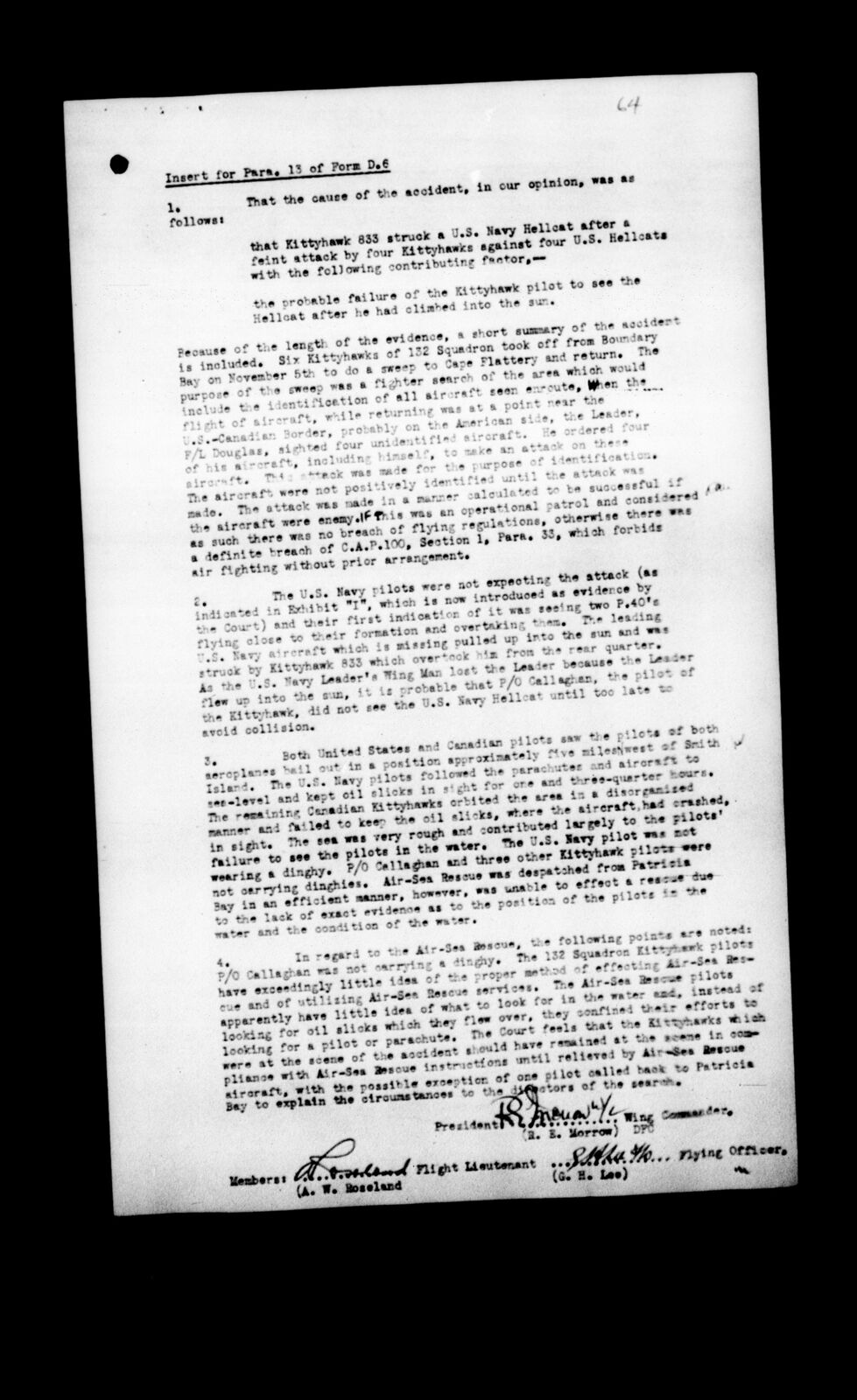

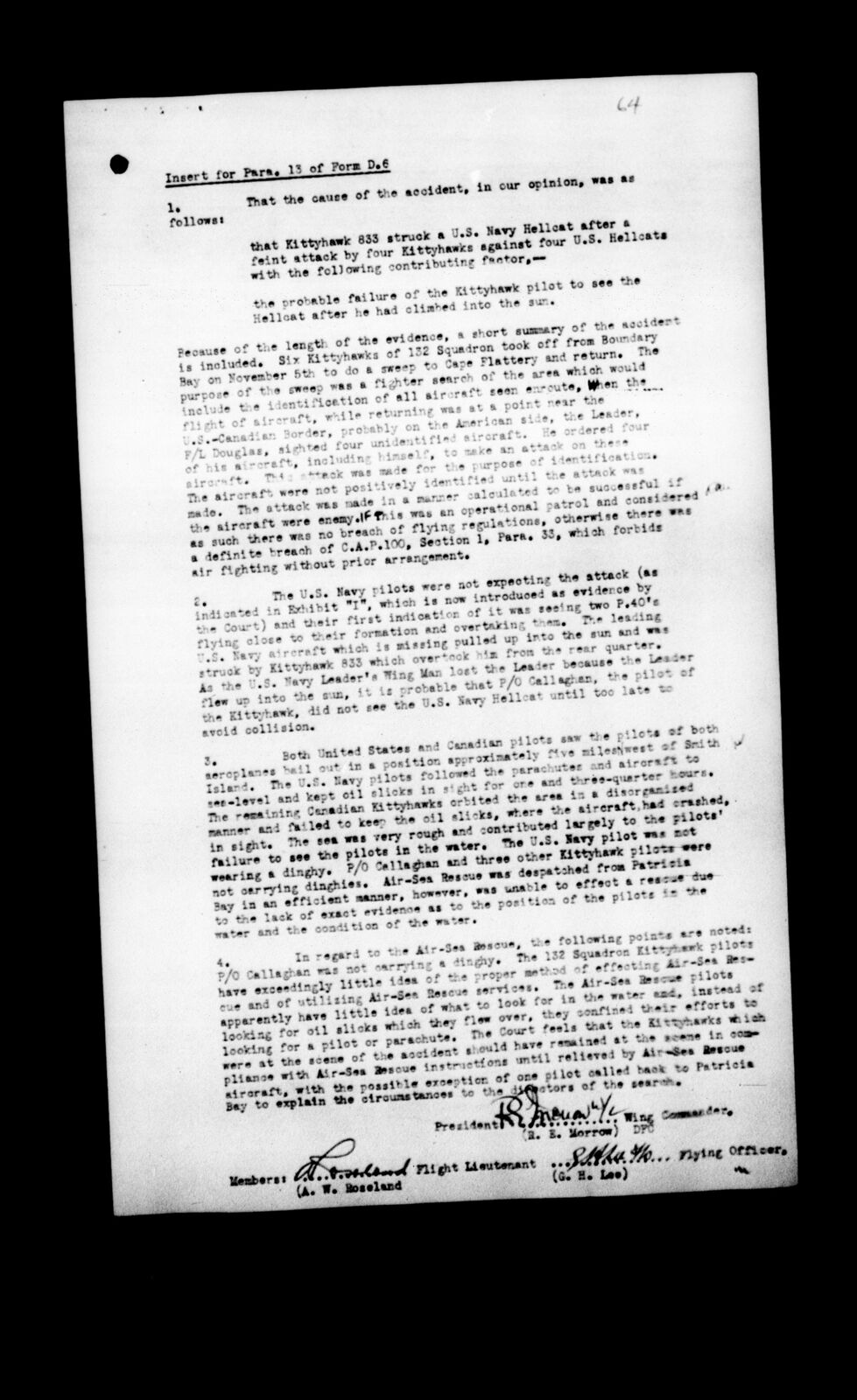

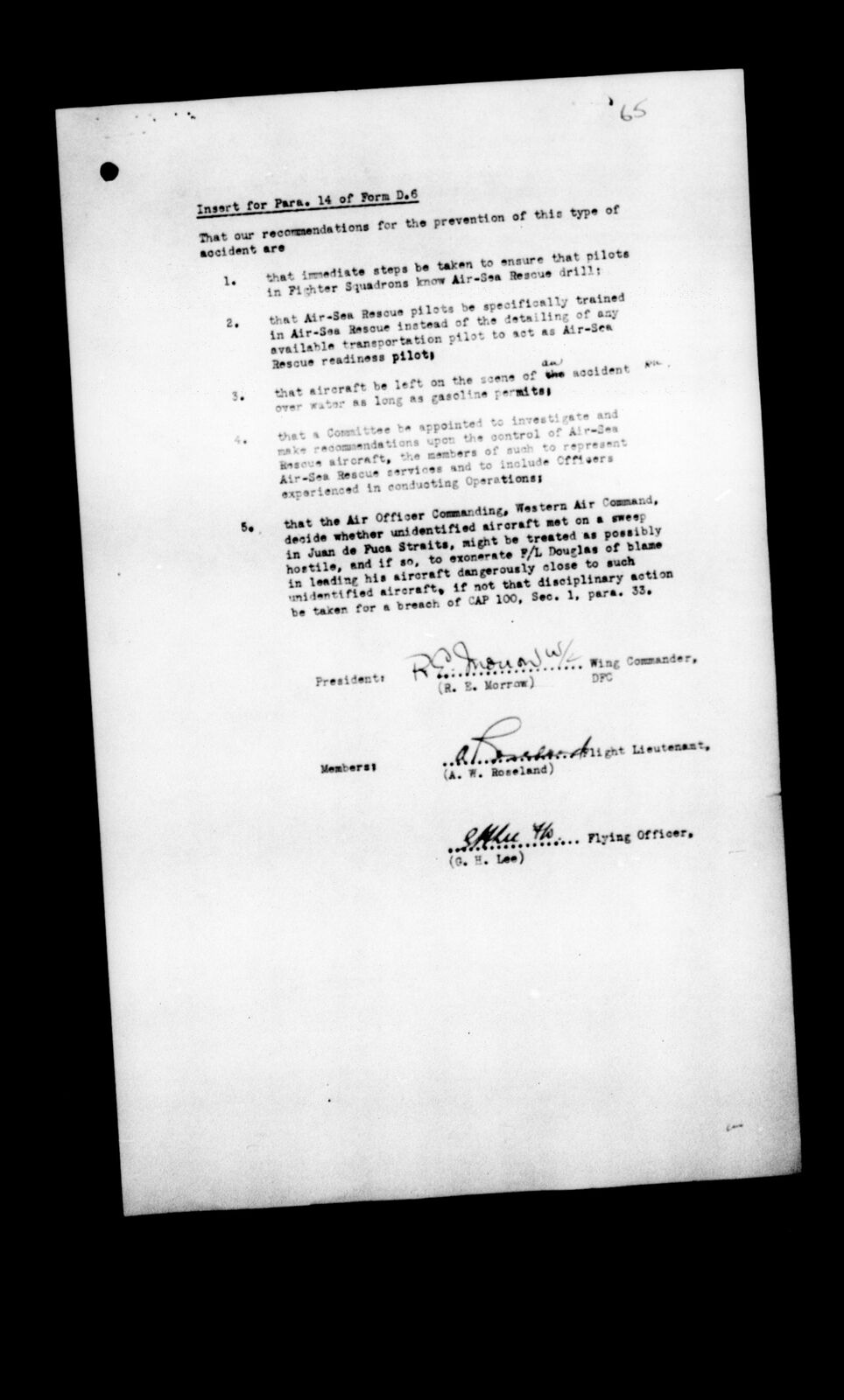

CAUSE OF ACCIDENT: That Kittyhawk 833 struck a US Navy Hellcat after a feint attack by four Kittyhawks against four US Hellcats with the following contributing factor: the probably failure of the Kittyhawk pilot to see the Hellcat after he had climbed into the sun… The missing US aircraft pulled into the sun and was struck by Kittyhawk 833 which overtook him from the rear quarter.”

In a memo dated November 18, 1943: It is considered that it was within the scope of the ffight Leader’s instructions to identify these aircraft but there was no justification for ordering an attack on a common type of US aircraft in the vicinity of a US naval training station.”

On December 7, 1943, a memo from A/C Guthrie wrote, “It is known, however, that the Officer Commanding No. 132 Squadron has been replaced in view of the fact that it became evident during the Court of Inquiry that pilots in his Unit were not always carrying K-type dinghies, and that air discipline in the Unit was not as satisfactory as it should be. Western Air Command has been requested to advise what disciplinary action has been taken in the case of the Flight Commander who led the attack on the US Navy Wildcats.”

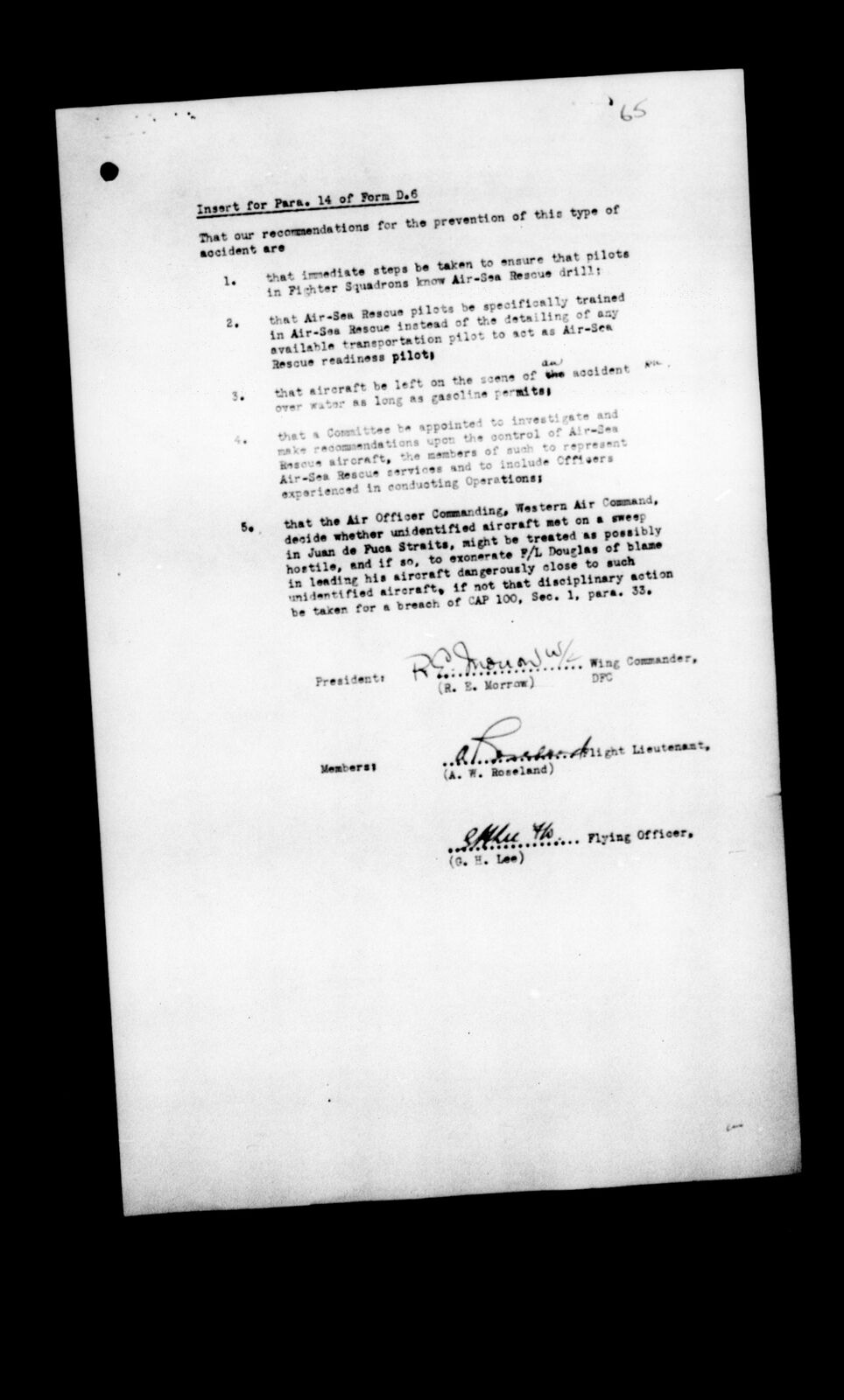

It appears that on December 6, 1942, F/L Douglas was charged under Section 40 for Breach of CAP 100 and remanded for summary of evidence. He could possibly have been exonerated of blame in leading his aircraft dangerously close to such unidentified aircraft that might have been treated as possibly hostile.

Keith Callaghan had $240 saved from his assigned pay in his mother’s name, plus $150 in Victory Loan Bonds and $1000 in life insurance.

Keith’s name is on the Ottawa Memorial and is also remembered on the family plot at the Sudbury Anglican Cemetery in Sudbury.