September 7, 1918 - April 22, 1943

John Joseph Bernard Martin was born in Antigonish, Nova Scotia, the son of Alexander and Annie (nee MacDonald) Martin. Mr. Martin was a diesel engineer. He had one older brother, Leo, and two sisters, Kathleen, younger, and Mrs. Virginia Melanson, older. The family was Roman Catholic.

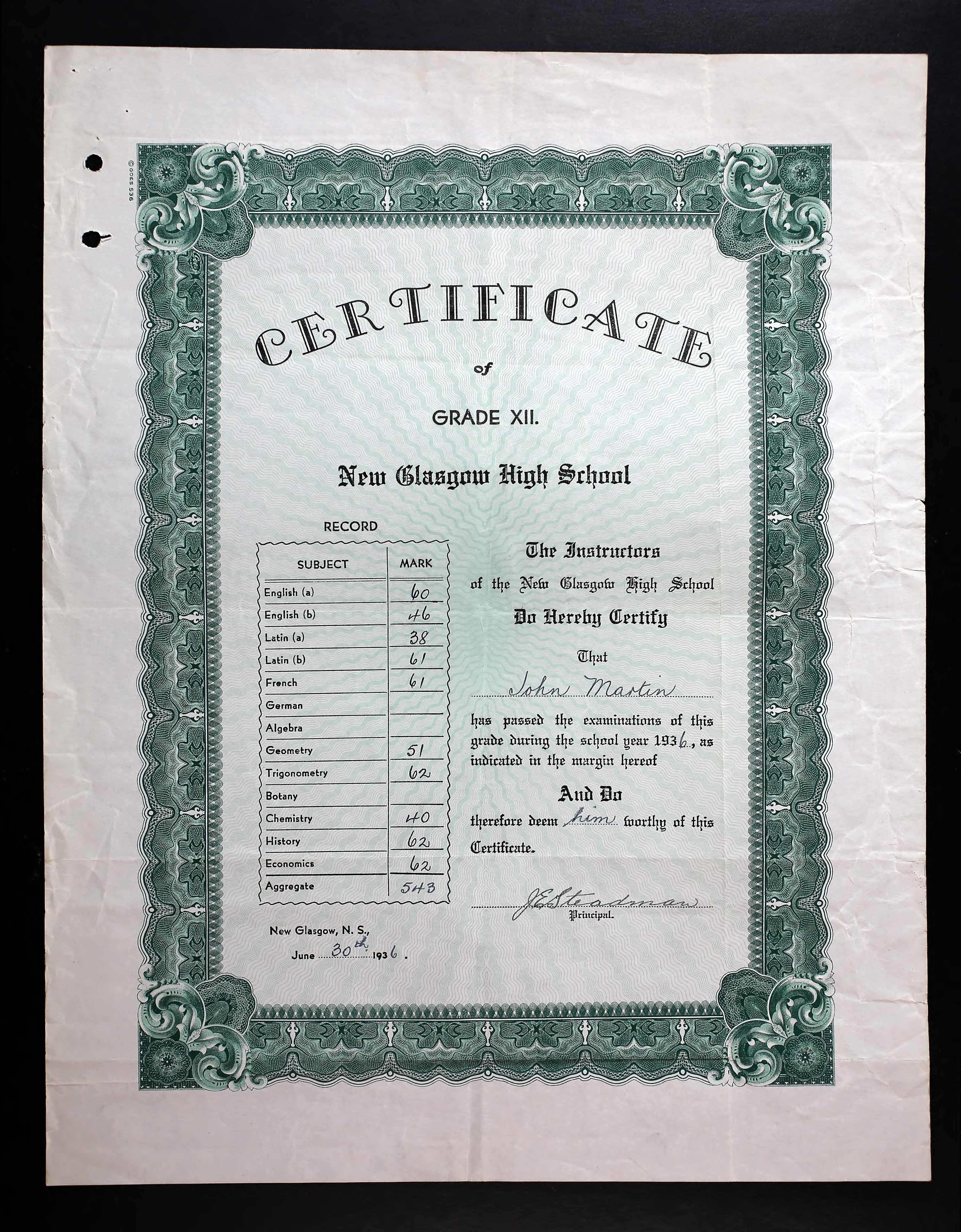

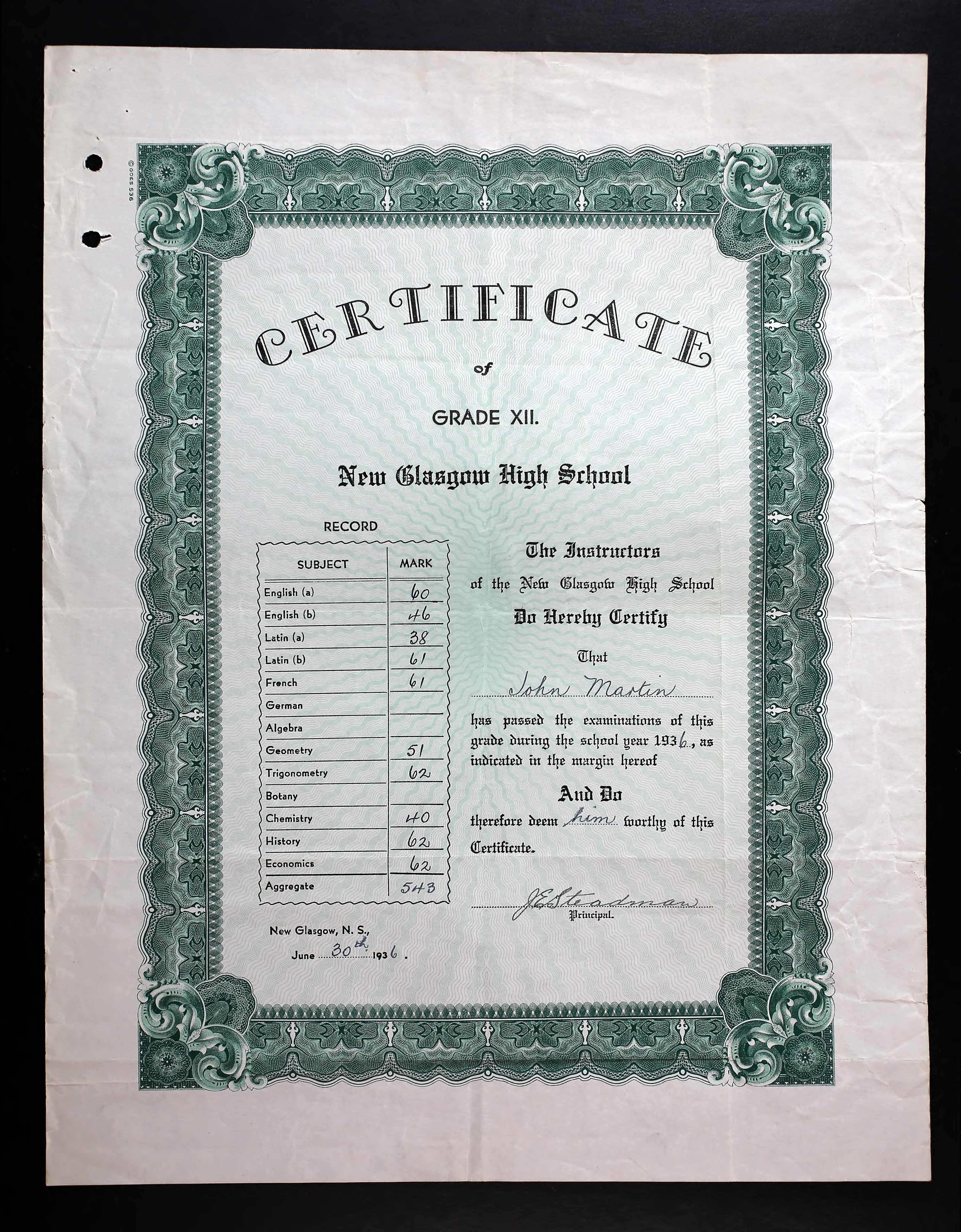

He had a Grade XII education, finishing school at age 18.

He worked as a junior clerk/teller/ledgerkeeper for five and a half years at the Royal Bank of Canada in Wymouth, Nova Scotia at the time of his enlistment in Halifax. He had 30 days of training with the West Nova Scotia Regiment, October 1940.

John enjoyed tennis but only played baseball from time to time. He could skate and ski, and hunt. He smoked ten cigarettes daily and indicated he did not consume alcohol. A tonsillectomy in 1932 and appendectomy in 1937, with scar, were noted on his attestation papers, dated November 27, 1941. He stood 6’ ½” tall, weighed 127 pounds, had dark blue eyes, black hair and a dark complexion.

Comments: “Very thin boy. He is alert, sincere. Only poor test is self-balancing.” Other observations: “This boy has two serious defects: 1. About 25 pounds below standard. 2. Failure in self-balancing. However his other tests are OK. He is alert, intelligent and good possibility he will be a pilot. He is bank clerk and should pick up in service.” The RCAF accepted John into service on December 10, 1941.

John was sent to Toronto, No. 1 Manning Depot on January 17 until May 9, 1942. Then he was at No. 1 Initial Training School, Toronto until August 15, 1942.

In May 1942: “Lad of average intelligence but rather less than average emotional stability. Not very aggressive. Fairly alert and quick. Has driven a car very little. Was afraid of the water and did not learn to swim until 4 years of age.” F/L C. G. Stogdell. F/L W. K. Kerr wrote, “Choice: Pilot, Observer, or Wireless Air Gunner. Senior Matriculation. Bank teller five years. Average or better intelligence. Sincere and good motivation, but had no previous interest in flying or mechanical hobbies. Only limited sports and is a tall, very slim, nervous lad who tries too hard and will probably fail because of nervousness. Fair as observer.”

John was sent to No. 20 Elementary Flying Training School in Oshawa August 16 until September 18, 1942, when he was washed out of flying. John was sent to Trenton on August 19, 1942 while it was decided what other flying duties John could do.

While at the Reselection Centre, Trenton, Ontario on October 14, 1942, John was confined to barracks for three days. “Neglecting to obey station standing orders. Appeared on parade wearing a non-issue shirt contrary to Section 2, Para. 2, Section 11.”

It was decided that John would become an Air Bomber. John was on an air bomber’s course at Paulson, Manitoba from October 26 to December 18, 1942, 9th in his class with an 84.2%. Ten days later, he took another air bomber’s course in London, Ontario from December 28, 1942 to February 5, 1943. He passed 13th in his class out of 24, with a 72%. He earned his Air Bomber’s Badge on February 5, 1943. “Inclined to be stubborn. Needs checking to get his work done.”

John’s father paid $150 for John’s Officer’s uniform.

John took out a $2500 life insurance policy with Canada Life Assurance Co and $1000 with the Royal Bank Group Insurance.

By April 4, 1943, John was at Y Depot, Halifax, and awaiting transport overseas. Sometime later, he, with 36 other RCAF airmen, boarded the Amerika. On April 22, while on its way from Halifax, Nova Scotia to Liverpool, it was torpedoed as the ship was heading to Britain. It was a straggler in convoy HX-234. Thirty-seven men, all officers in the RCAF, were presumed missing as a result of enemy action at sea including John. Their ship was sunk by U-306, south of Cape Farewell, off Greenland.

Forty-two crew members and seven gunners were also amongst those who were lost. The master, Christian Nielsen, 29 crewmembers, eight gunners, and sixteen passengers (RCAF airmen) were picked up by the HMS Asphodel, and landed at Greenock. General cargo, including metal, flour, meat and 200 bags of mail were also lost.

Mr. and Mrs. Martin received a letter in June 1943 from F/L W. R. Gunn, RCAF Casualties Officer for Chief of the Air Staff. "Since my letter of May 6th, no additional news has been received. Attached is a list of the names and next-of-kin of sixteen Royal Canadian Air Force officers who embarked on the same ship as your son and following enemy action at sea were safely landed in the United Kingdom. The following official statement was made in the House of Commons....’I have been in receipt of communications from a number of members of this house and from people outside with reference to rumours regarding the recent loss of a number of members of the RCAF by the sinking of a ship in the North Atlantic and I desire to make the following statement on the facts. The vessel in question was a ship of British registry of 8,862 tons, designed for peace-time carriage of both passengers and freight, and having a speed of fifteen knots. She carried a crew of 86 and the passenger accommodation consisted of 12 two-berth rooms with bath and 29 other berths, providing cabin accommodations for 53 passengers. She was fitted with lifeboat capacity for 231 and travelled in naval convoy. Under the recently revised regulations agreed to by the United States authorities, the joint United Kingdom and United States shipping board, the Admiralty, the Air Ministry and the Canadian authorities, a vessel of this description travelling in convoy is permitted to embark as crew and passengers a maximum of 75% of the lifeboat capacity. The lifeboat capacity as stated above was 231, 75% of which is 173. Personnel on board consisted of the crew of 86, and RCAF personnel numbering 53, a total of 139, well within the prescribed limits. Because of the superior type of available passenger accommodation, the speed of the ship and the provision of naval convoy, the offer of the entire available space to the RCAF was immediately accepted. Rumours to the effect that this was a slow freighter not suitable for passenger accommodation are, of course, not in accord with the facts. Every precaution was taken to safeguard the lives of these gallant young men. It should be pointed out that on account of the serious shipping shortage every available berth on such ships must be used, and had the space not been taken up by the RCAF officers of the other arms of the services would have been placed on Board. It should also be stated again that the submarine is still the enemy’s most powerful weapon and that the Battle of the Atlantic is not yet won. Any ocean trip today in any part of the world is fraught with danger and I think I may safely say that our record in transporting our soldiers and airmen to the United Kingdom is one of while we may all be proud. No one deplores more than I do the loss of 37 of the finest of our young men who gave their lives for their country as surely as if they had done so in actual combat with the enemy, and I extend my deepest sympathy to their loved ones in their bereavement.’ If further information becomes available, you are to be reassured it will be communicated to you at once. May I again extend to you my sincere sympathy in this time of great anxiety.:

Mrs. Martin was still not satisfied. "Dear Sir, Is it possible for you to give me any information on the above named! Is there anything left for us to hope for. On all sides we hear comment on the very unsafe way those men had been sent across [the Atlantic]. We were always of the impression that their safety was insured until at least they were in operational service. Have the names of any of the survivors being released? If we could get the addresses of any of those, we might learn something more than we now know. Hoping to hear soon regarding this matter. Yours truly, Mrs Annie J. Martin "

Mrs. Martin requested the addresses of some of the survivors and elicited at least one reply. Mrs. Kidd, her son, P/O Terence (Terry) Kidd who was also listed as missing, wrote to Mrs. Martin suggesting an enquiry letter be sent to a P/O Cecil [Eski] Mohs, one of the RCAF survivors. Terry and Cecil were friends.

In the summer of 1943, John’s sister, Virginia wrote to Cecil Mohs, one of the survivors of the Amerika. Cecil wrote back from England.

"Dear Virginia, I received your letter today and am going to answer it right away. I have often wished that I had your address for I would have written long before this. First though I wish to extend my deepest sympathies as I knew Johnny quite well. He shared his stateroom with my chum who was lost and their stateroom was next to the one I had. Consequently, we had many a long chat. I enquired from several of the chaps that I met after we arrived here, if they knew Johnny or if they knew anyone who might have known him. All I could find out was that the boys that were in his class had either left the station we were on or were still back in Canada. There isn't an awful lot that I can tell you Virginia, but what I do know will probably be appreciated. I wish it could be more hopeful news but I know you wouldn't want me to hold anything back from you. I might as well start from the beginning as you might understand the whole incident better. I was sitting in Johnny's cabin along with my chum and three other chaps. Johnny was up in the lounge room and we were just going to start a game of bridge when the first torpedo hit the ship. As I was going out the door to go to my own stateroom for my lifebelt, I met Johnny coming for his lifebelt. Just then the second torpedo hit and Johnny came out with the remark, “Boy those Huns must mean business. Hurry Mohs and I will meet you on deck.” I went into my cabin, grabbed my lifebelt and raincoat. I don't know what made me take my coat but it was just luck I guess. When I went up on deck, Johnny was already in one of the lifeboats and as it looked pretty well filled, I got into another along with Terry Kidd, my chum, johnny's roommate, and four other chaps all went through the same course with me. The lifeboat Johnny was in got away from the ship OK, but it was the last I saw of any of them. The lifeboat we were in had just got away from the ship when a huge wave got us and sank the lifeboat. The seas were very rough that night and it was snowing. There were about 25 in our lifeboat which included seven of us and the rest were ships crew. The lifeboat floated about a foot under the water and we were able to stand in it although we were in water up to our chests. There were some of the crew that got washed out and my chum and another kid by the name of Fred Keys from Toronto. I never saw my chum again but managed to get Fred back into the boat. The water was so cold that after about an hour and a half to two hours all the boys had died from exposure and I was the only one left alive. I had my raincoat wrapped around Fred and myself to keep the water out but Fred went and I passed out for a short time myself. When I came to, I was awfully sick from the swallowing of so much water that I decided I had to do something. I was so numb from cold that I had to wrap my arms around a rope that goes around the outside of a lifeboat and just sort of hung there so as my head couldn't drop into the water. I had my raincoat wrapped around my head to keep from taking in anymore water. That was the way I was when the Corvette picked me up. I was the last to be picked up and it was 4 1/2 hours after we were torpedoed. I I only have a hazy recollection of being taken on the Corvette. You will wonder at me telling you all this, but it will give you an idea what any of the others had to go through if they were in the water and what little chance there was for them. When I was on the Corvette, they told me that all the lifeboats and rafts been found. The one Johnny had been in was empty as were several of the rest as well as most of the rafts. This is very blunt Virginia, but I don't like to see you and your mother living in false hopes when there are none. I hate to write this but also I didn't want to hold anything back and it is what Mrs Kidd asked me to write her. You have my promise though that the bombs I drop will have johnny's name on them and although it won’t bring him back, they will be dropped with his regards. There weren't any of the survivors in the boat Johnny was in and I don't think any of them knew him only slightly. We hadn't been together long enough for everyone to know one another, only by sight. I am very sorry this couldn't have been a more cheerful letter but hope it will help to ease your mind. Johnny was not injured in any way and believe me Virginia when I say that he didn't suffer. It is just a numbness that keeps creeping through until you pass out. If there is anything that I have left out that you would like to know please write and let me know and I will do the best I can to answer it." Very sincerely Cecil Mohs

In early January 1944, John’s parents received another letter from S/L W. R. Gunn that their son would now be presumed dead for official purposes.

In October 1955, Mr. and Mrs. Martin received the letter from W/C W. R. Gunn informing her that John’s name would appear on the Ottawa Memorial, as John had no known grave, expressing sympathy on the loss of their gallant son.