April 19, 1916 - May 19, 1944

John Joseph Henry Cowan was the son of Robert Henry Cowan (1880-1952), hardware merchant, and Isobel (nee Sicard) Cowan (1882-1928) of Alexandria, Ontario. Mrs. Cowan died in an accident. He had another brother, LeRoy Clarke Cowan (1907-1927), in an accident, as well as another brother who died in infancy. He also had a sister, Isabel Harriet Anderson, living in Tennessee. Mr. Cowan remarried. John’s step-mother was Evelyn Alma Cowen. The family attended the United Church.

He married Elizabeth Marian McMaster in Montreal, Quebec on May 19, 1938. They had one son, LeRoy Henry Cowan, born August 19, 1938 in Montreal. He had been living in Quebec and worked at Canadian Radio Corporation and was servicing radios from 1935-1939. He then worked for his father as a hardware clerk and did radio servicing.

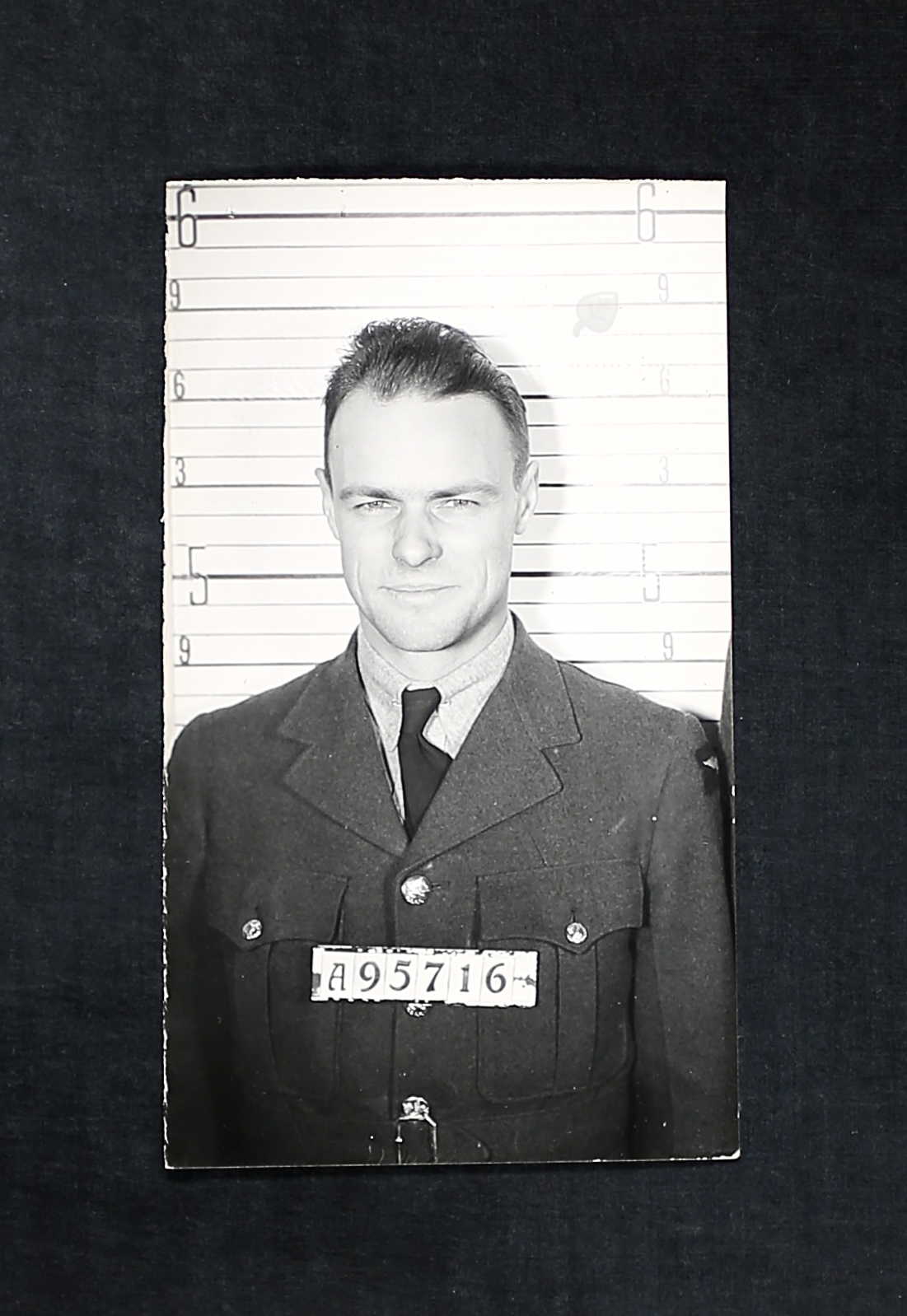

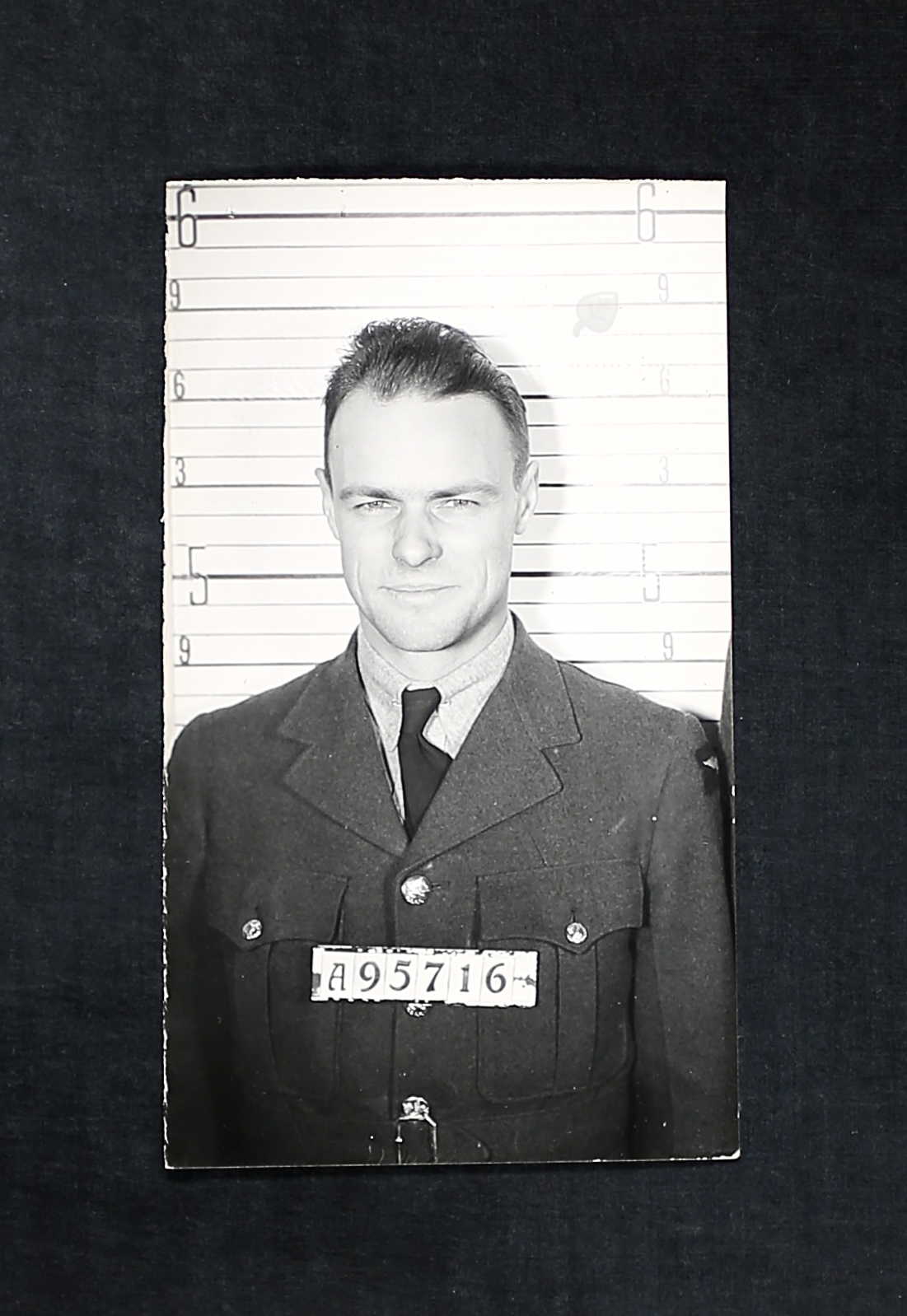

On August 3, 1940, John enlisted with the NPAM, remaining with until March 14, 1941 when he enlisted with the RCAF. He had applied to the RCAF in April 1940. He stood 5’8” and weighed 118 pounds. John had blue eyes and brown hair. By the time he was with the RCAF, he put on four pounds. He liked badminton, tennis, softball, curling, and hockey. “Have constructed sound amplifiers and radios.” He noted photography as a hobby and collected fire arms. “Alert, keen, and anxious to fly. Nice personable chap. Polite, well-mannered. Good material.” He was recommended to be a wireless operator, air gunner. John had hoped to enlist in mechanics. He had fractured his right ankle in 1933 but had no issues. He smoked ten cigarettes per day and drank a glass of beer a month. “Wiry lad, good responses. Abdominal reflexes absent but this does not seem to have any importance.” After the war, he hoped to operate his own electrical business.

From No. 1 Manning Depot, in Toronto, John was sent to No. 4 Wireless School, Guelph, Ontario from February 16 to August 3, 1942. He was 42nd out of 98 in his class, with a 78.8%, earning his Wireless Operator’s Badge. He was then at No. 1 B&G School, Jarvis, until August 31, 1942, where he was 14th out of 42 in his class. “An above average student. Capable and intelligent. Excellent type. Good judgment and initiative; may be trusted with a job calling for leadership and responsibility. Suitable for Commissioned Rank.”

John was at No. 34 O.T.U. Pennfield Ridge, NB September 15, 1942 until he was sent to Eastern Air Command in Halifax October 5, 1942. From there, he was taken on strength at No. 11 BR Squadron at Dartmouth, NS.

On February 17, 1944, John was “reliable and efficient takes an interest in all he does.”

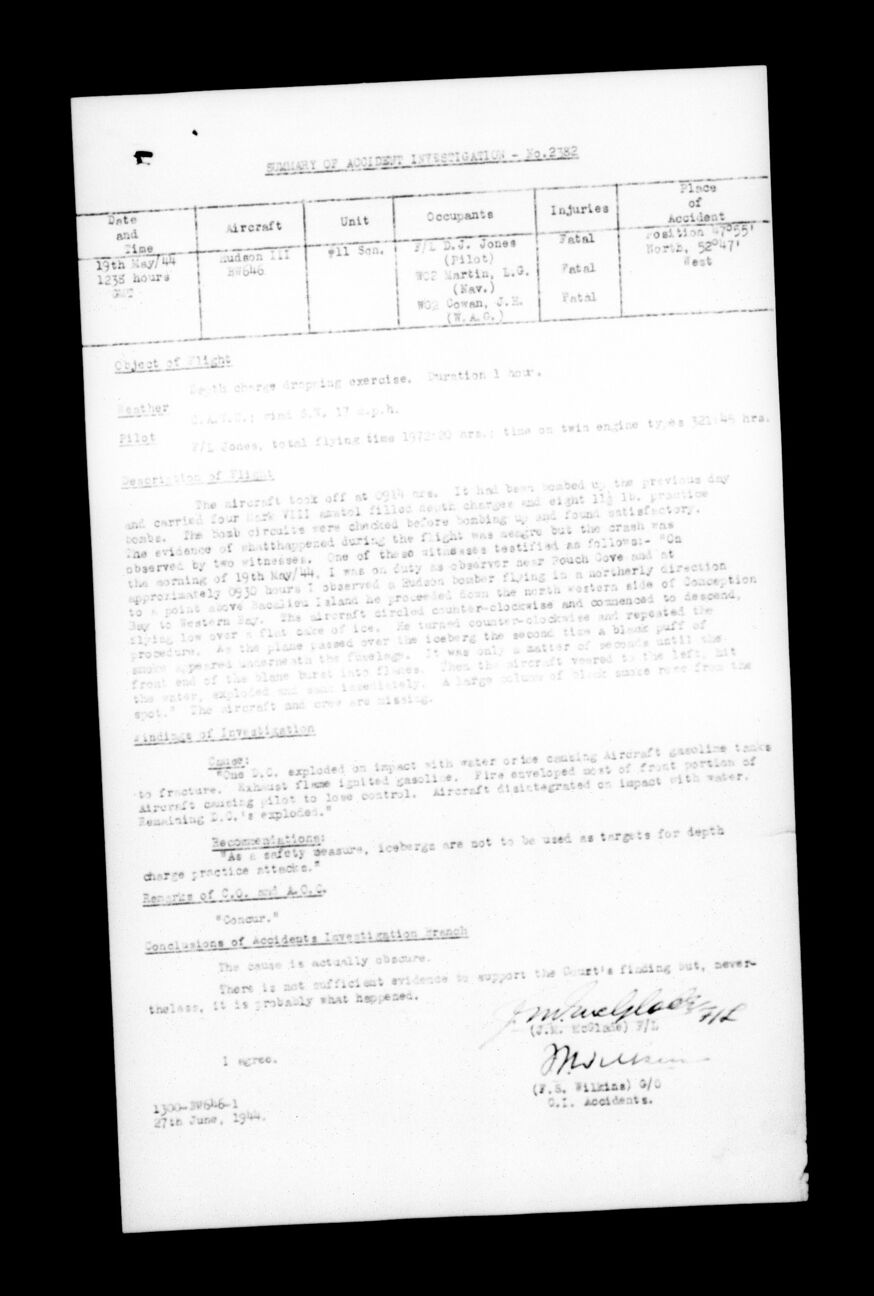

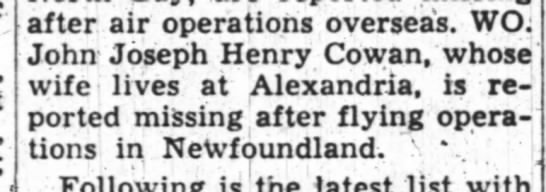

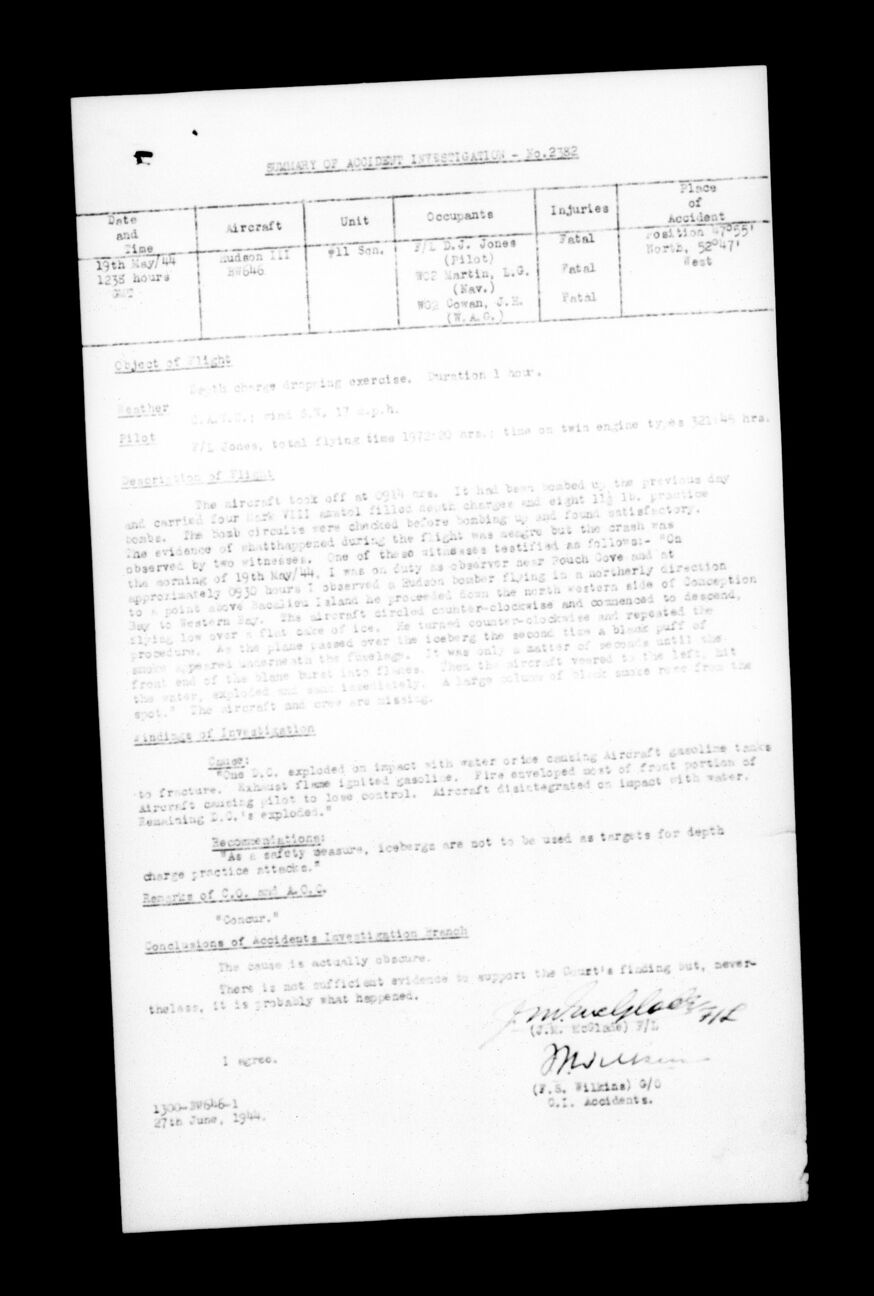

SUMMARY: Aboard Hudson BW646, 11 BR Squadron, Torbay, Newfoundland, were WIRELESS AIRGUNNER WO1 John Henry Cowan, R95716, PILOT F/L Douglas Jackson Jones, J5664, and NAVIGATOR WO1 Laurence George Martin, R134391. The aircraft was taken on strength February 5, 1942, by Eastern Air Command for Home War Establishment, one of 55 Hudson’s released off a British Lend Lease contract. Hudson BW646 failed to return from patrol on May 19, 1944, after a depth charge dropping practice. Position: 47 degrees 55 minutes north, 52 degrees 47 minutes west.

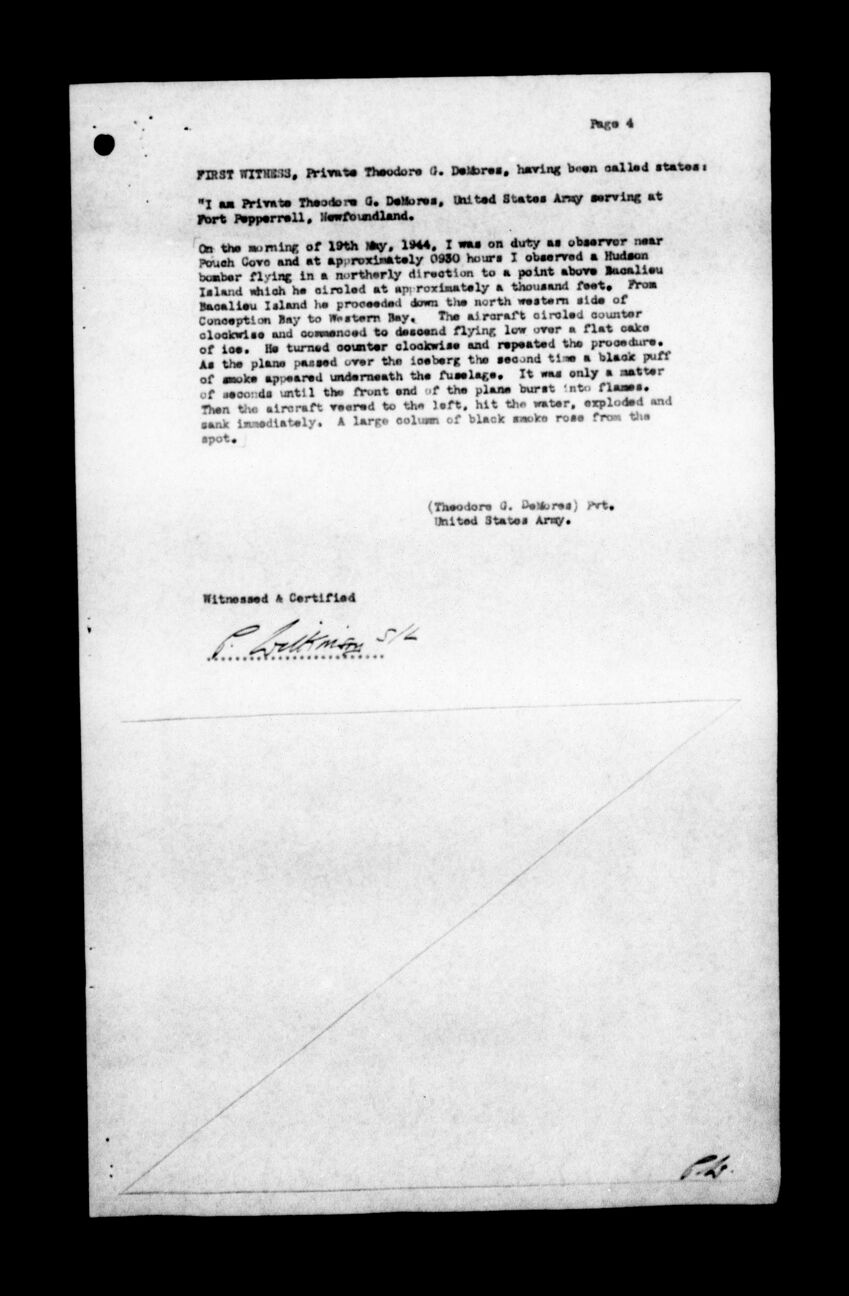

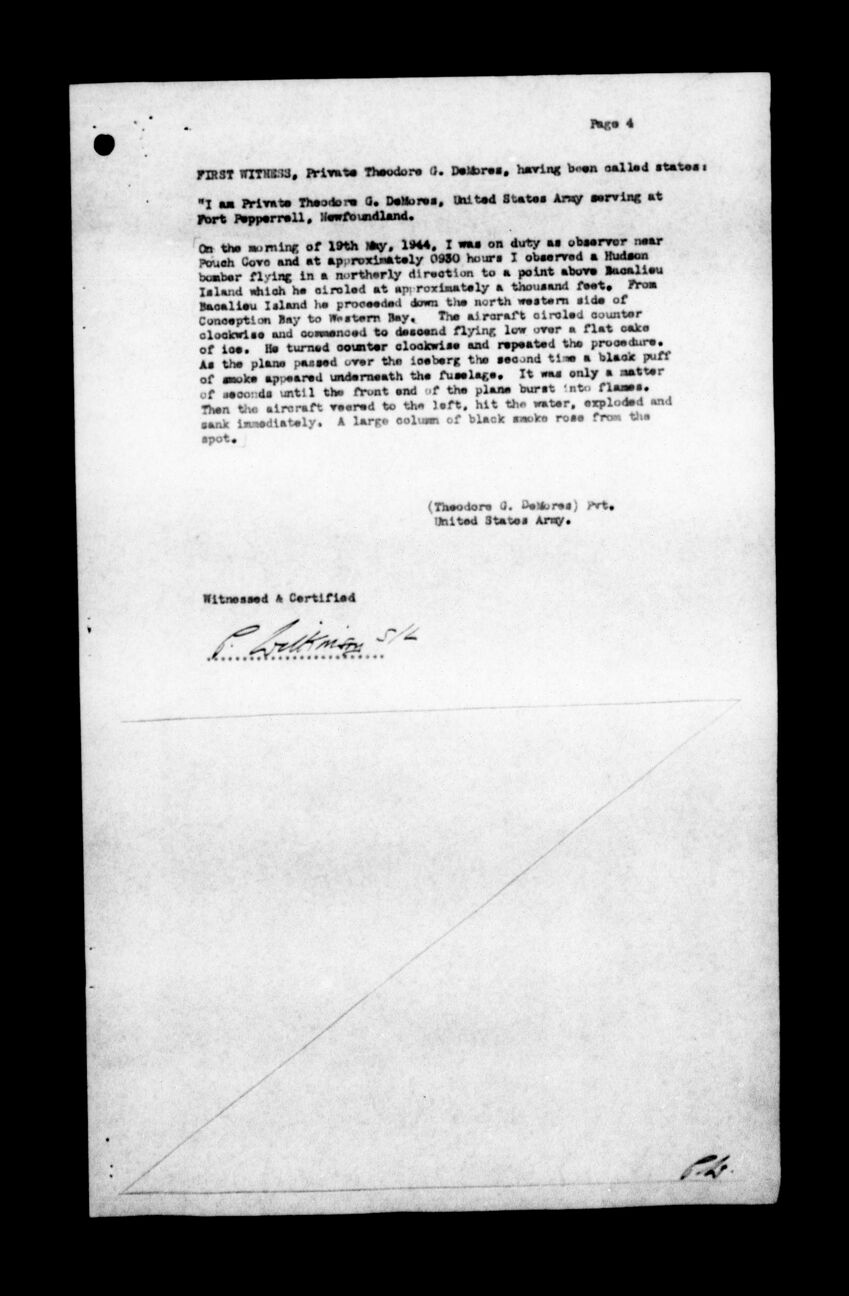

COURT OF INQUIRY: May 20 - 23, 1944. FIRST WITNESS: Private Theodore George DeMores (1919-2004), US Army serving at Fort Pepperrell, Newfoundland: “On the morning of May 19, 1944, I was on duty as observer near Pouch Cove and at approximately 0930 hours, I observed a Hudson bomber flying in a northerly direction to a point above Baccalieu Island [largest seabird island in Newfoundland, highest elevation 137 m, 449 feet, area 5 square km/1.9 sq. miles] which he circled at approximately a thousand feet. From Baccalieu Island, he proceeded down the northwestern side of Conception Bay to Western Bay. The aircraft circled counter-clockwise and commenced to descend flying low over a flat cake of ice. He turned counter-clockwise and repeated the procedure. As the plane passed over the iceberg the second time, a black puff of smoke appeared under the fuselage. It was only a matter of seconds until the front end of the plane burst into flames. Then the aircraft veered to the left, hit the water, exploded and sank immediately. A large column of black smoke rose from the spot.” SECOND WITNESS: Captain William Broderick, Master of fishing Schooner, Lady Bungay, of Grates Cove, Newfoundland, civilian stated: “I was sailing my schooner, Landy Bungay, down from Grates Cover to St. John’s on 19-May-1944 and at approximately 0955 hours, I saw an aeroplane circle low over an iceberg at about 150-200 feet. I saw one column of water rise from a point close to the iceberg. A short time after this, a red glow appeared at the front of the aircraft and the aircraft continued its descent into the water and blew up on impact with the water and a large column of black smoke arose from the spot. We felt the explosion when the aircraft hit the water and there was a large column of water arose with black smoke following.” FOURTH WITNESS: Cpl. William Mullen Mitchell, R117980, Armourer Bombs, No. 11 Squadron, RCAF Torbay, Newfoundland. He stated that “at approximately 1100 hours May 18, 1944, I supervised the bombing up of Hudson 646 with four Mark VIIII amatol filled depth charges and eight 11 ½ pound practice bombs. Prior to bombing up, normal checks on the bomb circuit were carried out and the circuits were all satisfactory. The aircraft did not take off that day as scheduled but took off the following day at approximately 0945 hours. The installation of the pistols on the depth charges are done by the HQ’s Armament Section. It is my opinion that a depth charge cannot explode while it is still on the carrier. There were no unauthorized explosives on board in Hudson 646.”

Operations was called to send a stand-by Hudson to the scene with Lindholme rescue gear. Canso 11054 was sent to the are to search for survivors. Canso 11054 reported finding an oil slick and wreckage six miles off mouth of Conception Bay in line with the mouth of the bay. Two other airplanes were involved in the search. An American crash boat was on its way to the scene, along with two naval boats form Belle Isle. A hospital boat was also sent. Hudson 632 called the position of the wreck six miles from Cape St. Francis. Canso 11054 and Hudson 632 were told to remain over the spot until the surface vessels arrived. Canso 9773 was also contacted, and they stayed out over the site of the wreck. [Canso 9773 was lost disposing of old dynamite May 20, 1944.]. Canso 9773 reported that there were no survivors, its pilot reporting he did not see any naval craft other than the American crash boat at the scene. [The first pilot aboard Canso 9773 was F/O Leo James Murray; the second pilot was F/L Alan Gordon Byers. Both their names are on the Ottawa Memorial, along with their crew. They were disposing of old dynamite over icebergs.] The wreckage picked up included a tire and wheel, one smoke bomb, one broken ammunition box (calibre 50) and one broken piece of floorboard. The President of the Court flew to the scene of the accident in Hudson BW403 with Lindholme gear and all that was seen was an oil slick and small bits of floating wreckage. The aircraft had sunk.

FINDINGS OF THE INVESTIGATION: CAUSE: One depth charge exploded on impact with water or ice causing aircraft gasoline tanks to fracture. Exhaust flame ignited gasoline. Fire enveloped most of the front portion of the aircraft causing pilot to lose control. Aircraft disintegrated on impact with water. Remaining depth charges exploded. Recommendations: as a safety measure, icebergs are not to be used as targets for depth charge practice attacks. Conclusions of Accident Investigation Branch: The cause is actually obscure. There is not sufficient evidence to support the court’s finding but nevertheless it is probably what happened.

MEMO: June 28, 1944: FIRE IN AIR IN HUDSON AIRCRAFT -- G/C F. S. Wilkins, CI Accidents 1. In view of the fact that we have had three accidents due to fire in air in Hudson aircraft and in each case the aircraft dived into the sea and no examination could be made, I detailed one of the staff to examine any Hudson’s within easy reach of Ottawa in an attempt to find where such fires could originate. Such an examination would, of course, not be conclusive but might give us something to work on. Flight Lieutenant pula examined a number of such aircraft at Rockcliffe. You will see by his attached report that the washers being used in gasoline filters are, in most cases, non-standard. One aircraft he examined showed definite signs of a gasoline leak from the filter having impinged on the inside of the Cowling. In addition to these failures, I attach two pieces of flexible hose from the same area of the engine installation which are unsatisfactory. The long piece is bent into a ‘U’ an dshows signs of failure from the fabric; The short piece has definite indications of cutting in by the clips. Any of these defects could come in the right set of circumstances, caused fire in the air. Two period when the defects concerning the washers were found, the unit could not obtain any standard washers and sent to Montreal for supplies. I spoke to D. R. M. About this shortage of washers. I have now been informed that all carburetor spares are concentrated in No. 1 E. D. Toronto. Toronto, as far as I know, has never had any number of Hudson aircraft station in the vicinity and I am very much of the opinion that the units equipped with Hudson’s are making up their own washers because they do not know where to obtain the proper ones.

After John’s death, Elizabeth was very pro-active in getting his estate settled. She wrote a letter in October 1944 about the damaged condition of John’s effects. “On opening the carton, I found that a mantle radio clock…has been smashed. One side completely broken and the dial and front cracked right across. A bed lamp which was in it was bent and also sock frames twisted beyond repair. The latter I mention only to show that there must have been great negligence in the packing of the parcel either at Torbay or in Ottawa or in the transportation by express for I know that the radio was in good condition while my husband had it.” Elizabeth requested that the radio and bed lamp be repaired by the RCAF or the CNR. She received a reply that the damage occurred while the effects were in transit from Torbay. It was suggested she lodge a claim against the transportation company. In April 1946, Elizabeth wrote to request her late husband’s operational wings. “I believe at the time of his death, he had almost the complete tour….I would greatly appreciate it if you would see that I receive the wings, and also the Atlantic Star and the 1939-45 Star once they are struck.”

John is remembered on a family headstone in St. Stephen’s Cemetery, Buckingham, Quebec, as well as on the Ottawa Memorial. Elizabeth had remarried by 1951, living in New York City. She and her husband, James B. MacDonald of Murray Hill, New Jersey, received the letter informing her that John’s name would appear on the Ottawa Memorial.

LINKS: