January 2, 1921 - April 2, 1944

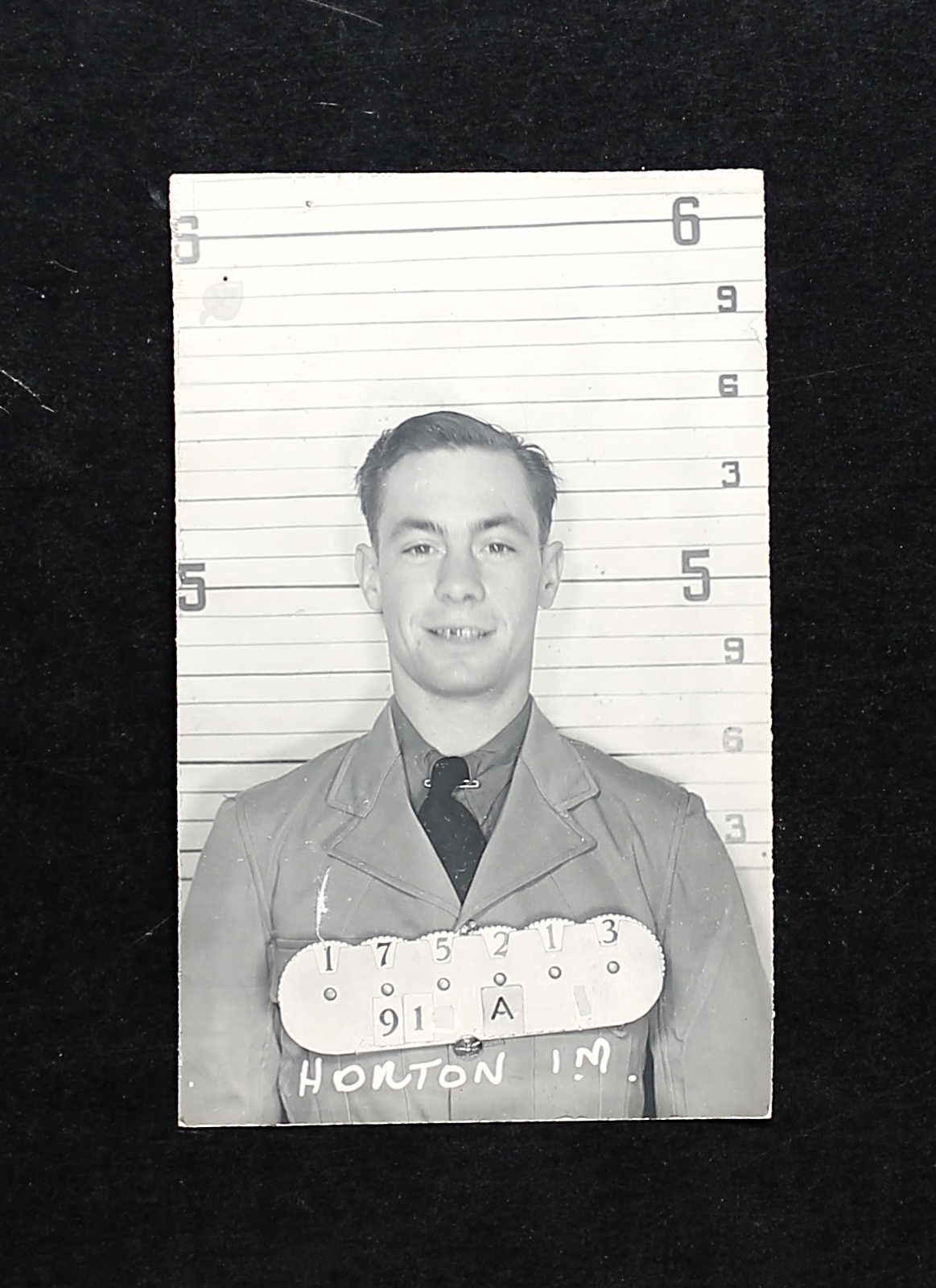

Ian McLane Horton, born in Sylvan Lake, Alberta, was the son of John Chambers Horton (1881-1951) and Laura Annie McLane Horton (1885-1954) of Oshawa, Ontario, later of Whitby, Ontario. He had one brother, Philip, also in the RCAF, and one sister, Mrs. Lucy Irwin. The family was Anglican. Ian indicated his father was an invalid with bronchial asthma. The family moved often: from Alberta, they lived in Toronto, and Calgary, before returning to Ontario.

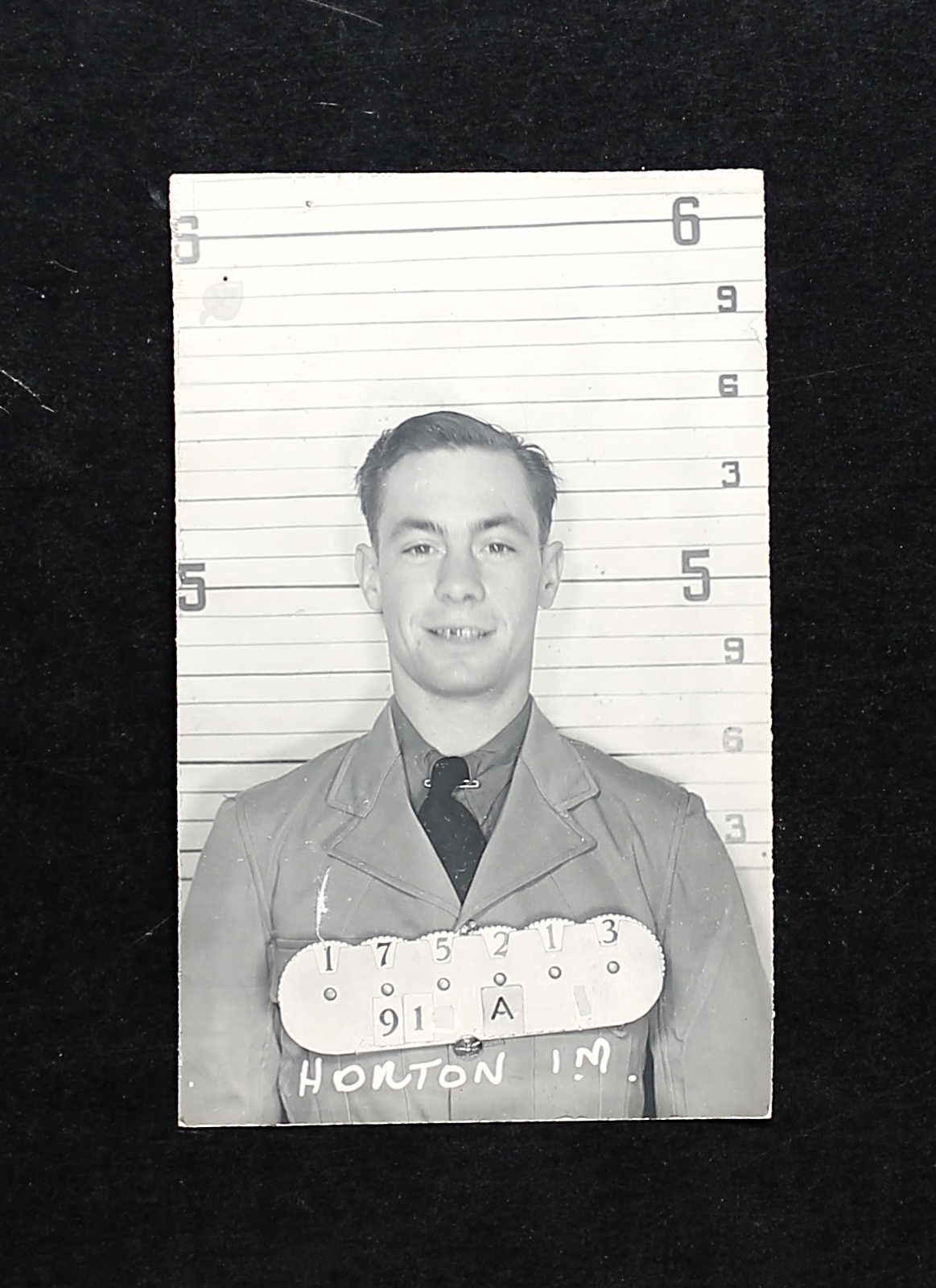

In 1939, he fractured his leg and clavicle. He stood 5’ 3 ¼” tall and weighed 125 pounds. He had brown eyes and dark brown hair. Ian smoked ten cigarettes a day, indicating he did not smoke cigarettes. His hobbies: kept pigeons and sports. January 21, 1942: “This boy is physically fit except for chronic obstructive appendicitis and history of convulsions. He is to have an EEG and to have OK by MSB. His visual acuity is only good enough for a pilot, otherwise he is in exceptionally good condition and probably would make a good pilot.” January 26, 1942: “This boy has been passed as far as his convulsions are concerned by MSB. He is still ATBT because of appendicitis.” In late January 1942, he had an appendectomy.

Ian was employed as a material follow-up worker [assistant purchasing agent] at General Motors of Canada from 1941-1942. Prior, he was a teller for the Canadian Bank of Commerce from 1939-1941, leaving that position to join GM. He had senior matriculation French and junior matriculation Latin. In 1937, he was at Garbutt Business College for two months in Calgary. He like to play hockey and was on the Lindsay Junior team, plus played baseball, tennis and rugby. He hoped to enlist in the RCAF as a clerk/accountant in January 1942. “Does not want to be called before June 30, 1942.” On his interview report: “Small, slender, neat, clean, average appearance, fair personality. Apprehensive, not too keen, has good educational qualifications, good family background. response quick. Played Junior OHA hockey last year; may become more enthusiastic in training. Average aircrew material. Preference Observer.” Ian was accepted into the RCAF in June 1942 for pilot training.

Ian started his journey through the BCATP at No. 1 Manning Depot, Toronto, Ontario August 11, 1942. He was then sent to No. 1 SFTS, Camp Borden, September 26, 1942 until January 23, 1943 until the RCAF found space for him at No 6 ITS in Toronto until April 3 1943. “A trainee who is young for his age. He gives an impression of insignificance partly through his physical build-up and partly through lack of aggressiveness. He had worked hard at the course and produced well; on the whole, just average material. Second Aircrew recommendation: Air Bomber.”

February 1943: “Good physical development. Complains of pain in feet when at drill. Has infrequent sharp pains in RLQ since appendectomy one year ago, now disabling. Alert, intelligent appears keen to fly.”

From there, he was sent to No. 12 EFTS, Goderich, Ontario April 4 until May 29, 1943. “Link mark: 77%. Average student. Should be checked for carelessness. Does not have enough self-confidence. Troubled in early training making gliding turns.”

He was then sent to No. 16 SFTS, Hagersville, Ontario May 31 until September 17, 1943. “Ground Examinations: 73.7%. Flying Tests: 67.7%. Good ability. Should steady down with experience. Extremely suitable for GR aircraft. Definitely suitable for Bomber type aircraft.”

He was then at No. 1 GRS, Summerside, PEI October 11 to December 10, 1943. “20th out of 24 in class. 70.65% Navigation Pilot’s Course. Keen and conscientious navigator who worked well. Confident but requiring steadying influence. Average results. Should prove steadier with more experience.” Ian was recommended for land-based GR, then fighter reconnaissance, and lastly for torpedo bombers.

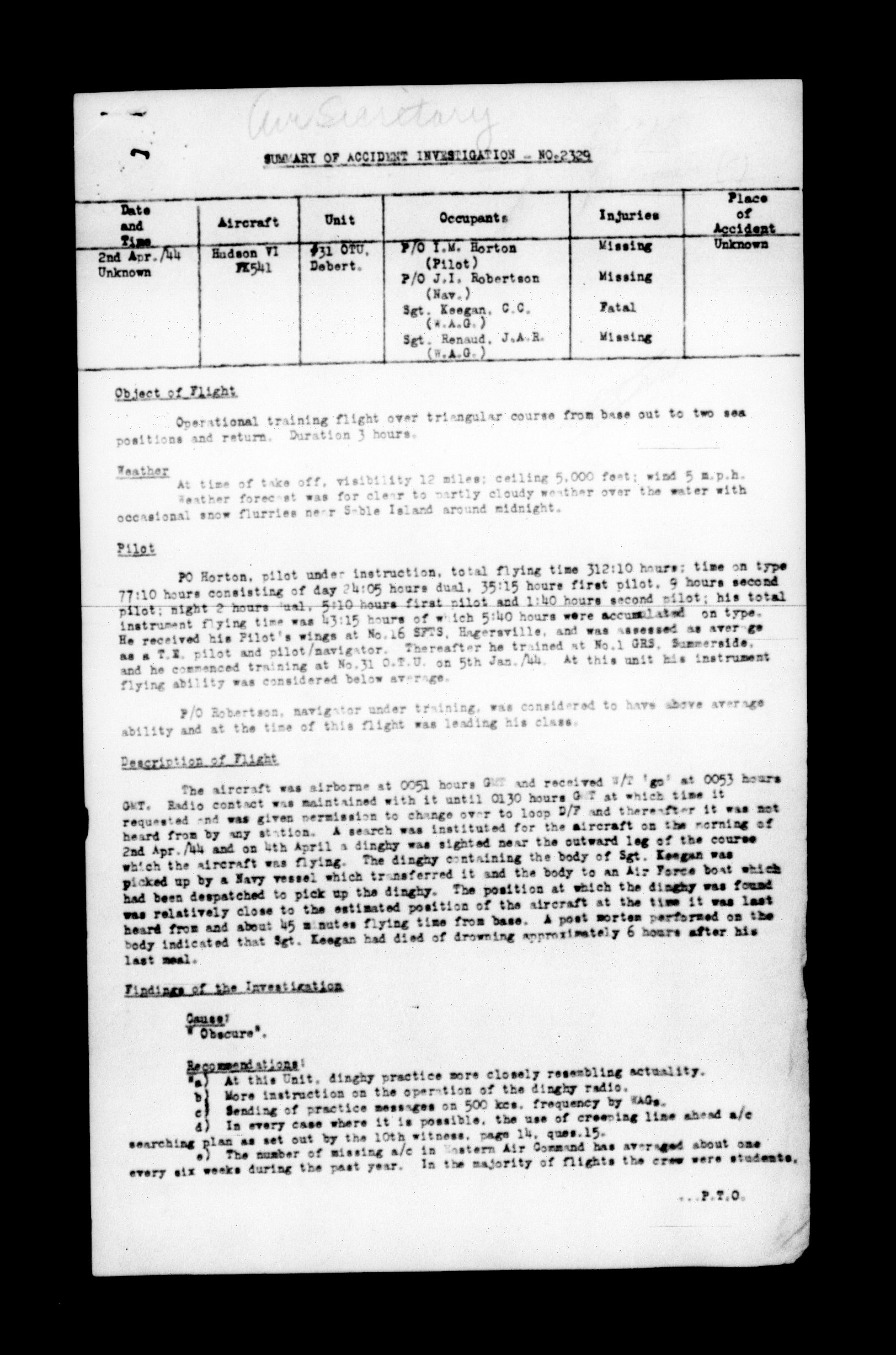

Ian was taken on strength at No. 31 O.T.U. Debert, Nova Scotia, January 1, 1944, commencing training on January 5, 1944. He was aboard the ill-fated flight of Hudson FK541 that departed Debert on April 2, 1944.

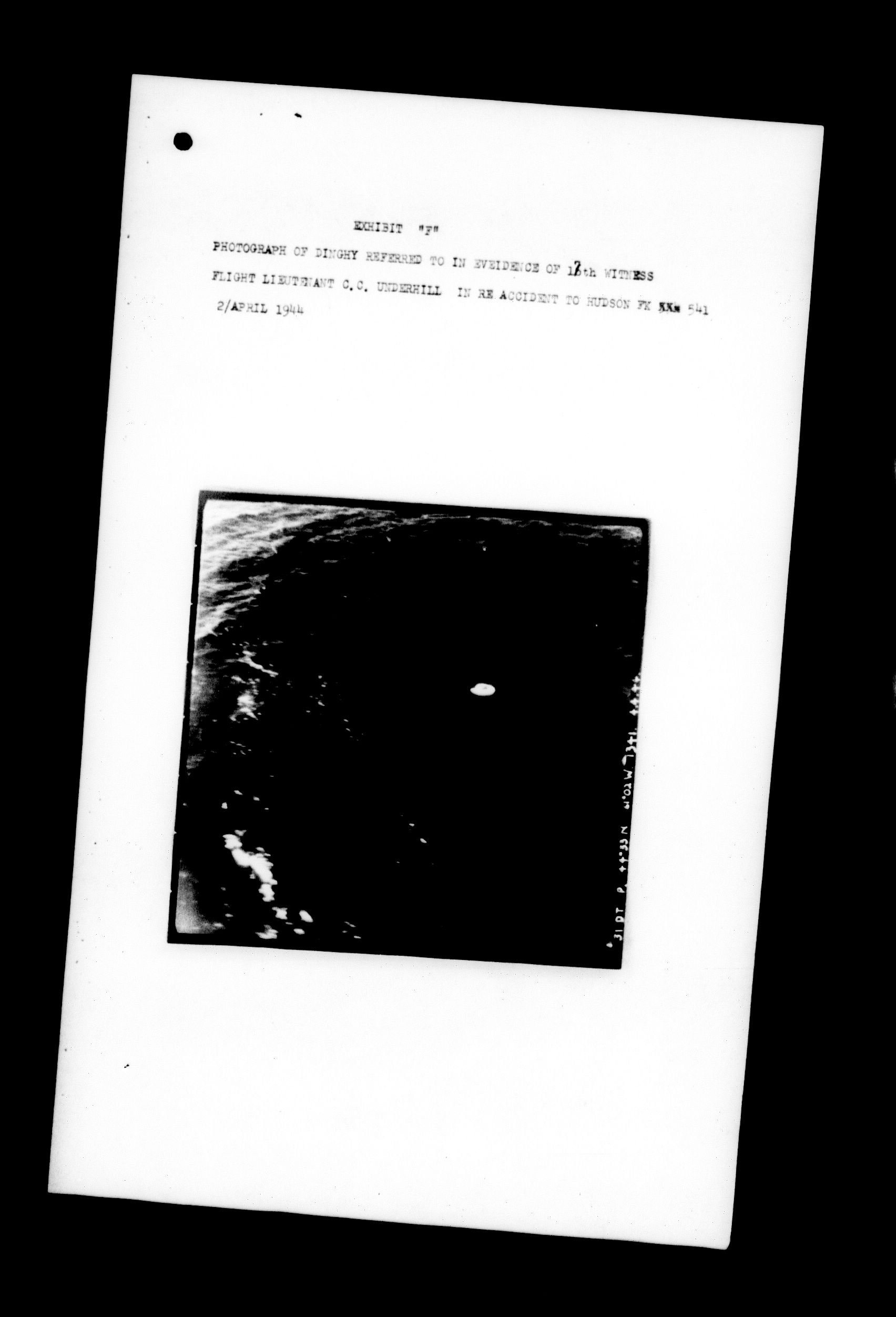

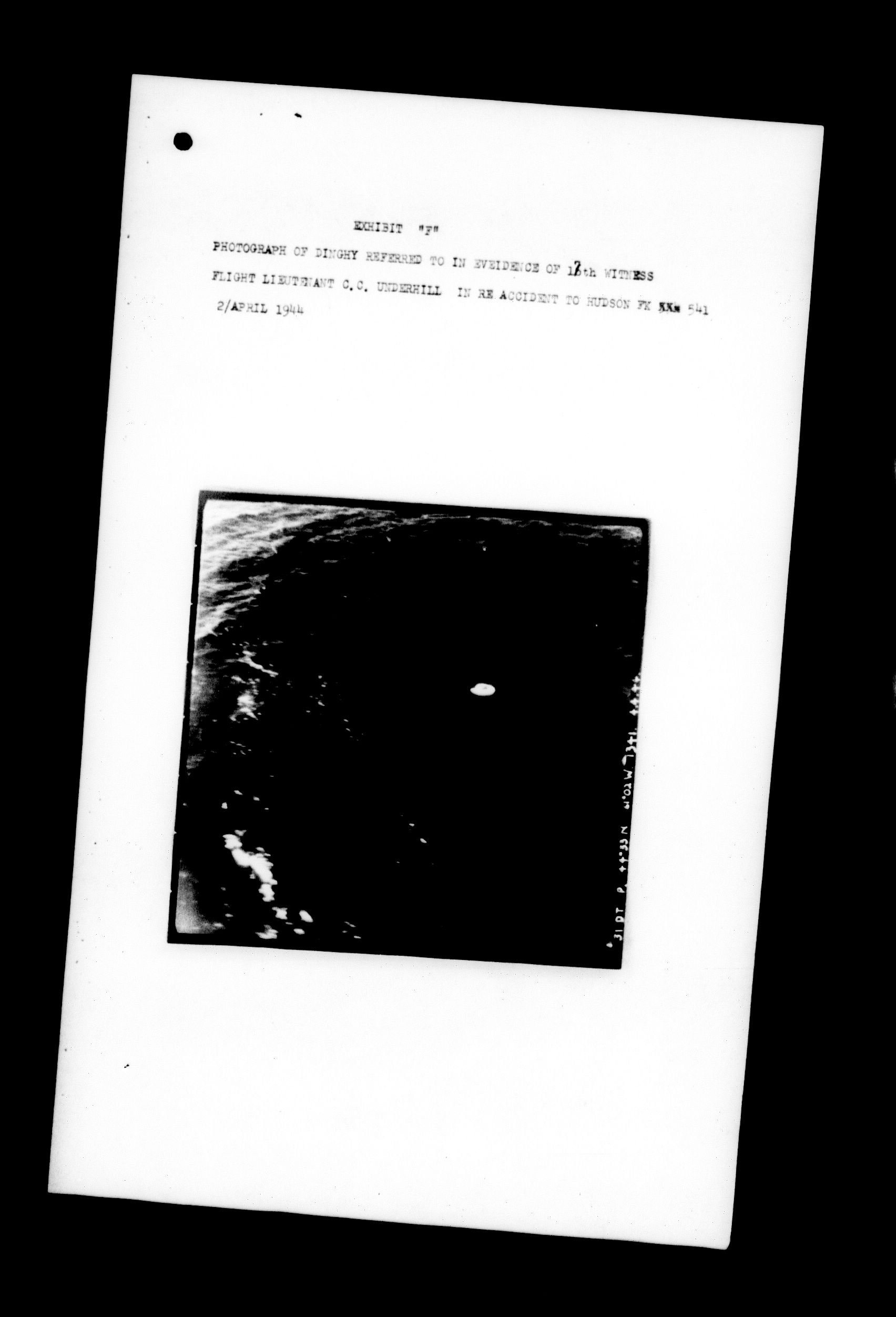

Court of Inquiry: APRIL 8 - 18, 1944 AT DEBERT, NOVA SCOTIA. Hudson FK541. Microfiche C5937, Image 4094. Seventeen witnesses were called. A map of the track of the aircraft, plus a photo of the dinghy were included as was the text of an article from the Halifax Chronicle.

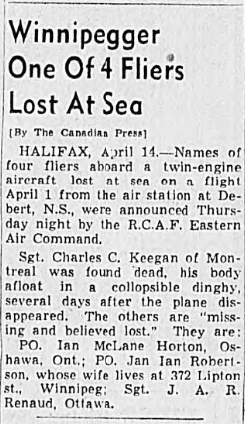

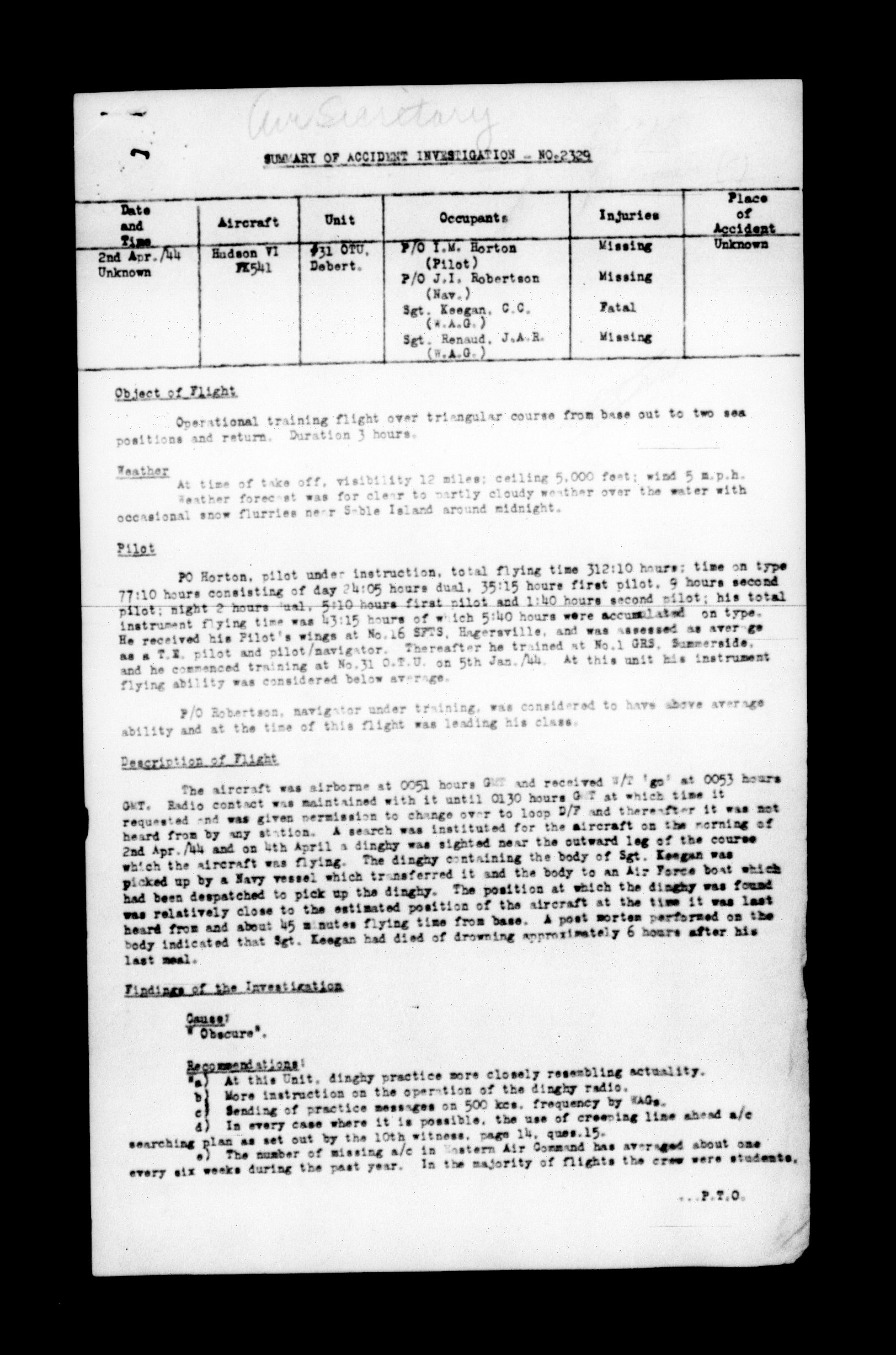

On April 2, 1944, CREW OF HUDSON FK541: PILOT F/O Ian McClane Horton, J25567, WAG Sgt. Charles ‘Clement’ Keegan, R185401, NAVIGATOR P/O Ian Robertson, J38435, and WAG Sgt. Joseph Alaric ‘Roland’ Renaud, R141551. The object of the flight was an operational training flight over a triangular course from base out to two sea positions [including Sable Island] and return. One message, badly garbled may have been received, but this could not be confirmed. Duration: 3 hours. WEATHER: At time of take-off, visibility 12 miles, ceiling 5,000 feet; wind 5 mph. Weather forecast was for clear to partly cloudy weather over the water with occasional snow flurries near Sable Island around midnight. PILOT: P/O Horton, pilot under instruction: total flying time 312:10 hours; time on type 77:10 hours consisting of day 24:05 hours dual, 35:15 hours first pilot; 9 hours second pilot; night: two hours dual, 5:10 hours first pilot and 1:40 hours second pilot. His total instrument flying time was 43:15 hours of which 5:40 hours were accumulated on type. He received his Pilot’s Wings at No. 16 SFTS Hagersville and was assessed as average as a T.E. pilot and pilot/navigator. Thereafter, he trained at No. 1 GRS, Summerside and he commenced training at No. 31 O.T.U. on January 5, 1944. At this unit, his instrument flying ability was considered below average. P/O Robertson, navigator under training, was considered to have above average ability and at the time of this flight, was leading his class. DESCRIPTION OF FLIGHT: The aircraft was airborne at 0051 hours and received W/T ‘go’ at 0053 hours. Radio contact was maintained with it until only 0130 hours at which time it requested and was given permission to change over to loop D/F and thereafter it was not heard from by any station. A search was instituted for the aircraft on the morning of April 2, 1944, and on April 4th, a dinghy was sighted near the outward leg of the course which the aircraft was flying. The dinghy, containing the body of Sgt. Keegan, was picked up by a Navy vessel which transferred it and the body to an Air Force boat which had been despatched to pick up the dinghy. The position at which the dinghy was found was relatively close to the established position of the aircraft at the time it was last heard from and about 45 minutes flying time from base.

The first witness, AC1 J. A. Hepburn, R184054, WO, No. 31 OUT Debert transcribed the signals in connection with Hudson FK541. He had been with the unit for four months. “The radio conditions on the night in question were very poor with a good deal of interference. There were two of us working on independent sets throughout the night. It took about 15 minutes to get the signal received at 0130 hours.” It was rare he received half hour reports that Operational Crews were instructed to send out.

The second witness, LAC G. Drummond, 1343111, WO stated that the signals were unreadable due to background noises. He had been with the Unit for 16 months. Regarding the half hour reports that operational crews are instructed to send out: “They do not call on our frequency unless they fail to make contact on Base frequency. However, we do receive these calls frequently. The radio conditions on the night in question were very poor.”

The third witness, Mr. A. L. Wright, meteorologist stated that there were conditions in the overcast report at Sable Island that would have made airframe icing possible.

The fourth witness, F/O W. N. Prentice, J17858, Navigation Instructor stated that he had known P/O Robertson for about three months. “He was the navigator of Hudson FK541, missing since April 2, 1944. I would rate him as an above average navigator, and at the time, he was leading his class. Prior to this last trip, the same crew did the same course in the daytime on March 25, 1944. They were rated on this as above average. The same crew also did another daytime trip of greater length and covering approximately the same area three days subsequent to the above. They had a very good rating on this one also. The distance between the position of the dinghy and the estimated position at the last signal was about 15 miles. As far as my personal experience in operations which covers a period of two years, WOs especially were sadly lacking in practical experience in the air.”

The fifth witness, S/L G. V. Smithers, 37742, Operations Controller, stated that the crew of FK541 had been briefed by F/O Pearson “some two hours prior to my coming on duty. F/O Pearson has since been posted away, therefore will not be available as a witness. However, as regards briefing of these crews, it was much the same in each case, and when I do the briefing, it follows along these lines: First, a crew is given the best route under the existing weather conditions, this being explained to them at the time. The height to fly at is also established. The importance of sending a minimum of half hourly messages to Base is explained.” He described the search for the missing aircraft, “decided upon was worked out by the Duty Navigator and covered an area of 12 miles on either side of the out-going leg from the coast to 10 miles beyond the first turning point. This was to be carried out by aircraft flying at 500 feet visibility distance of half a mile. The reason for putting the search on this area was due to the fact that the last message came from the aircraft at about that turning point and if it had ditched at that time or shortly after, the tide would have drifted the dinghy somewhere into that area. At the same time if it had ditched earlier, the outward leg was fully covered. At 0200 hours 4th April, a message was received saying that a Ventura aircraft saw what looked like a partially inflated dinghy at 2330 hours. This was seen by the wireless operator and navigator but was lost when the Ventura turned to have another look…. At 1350 hours, message received from aircraft T3 circling dinghy... no live occupants.... they told me that they would contact the Navy to send a rescue ship. I asked if a Canso could be sent out but this was not done. Aircraft T3 was told to circle position then land at Dartmouth. At 1408, aircraft X2 which was also on the search was joining T3 to check position and to assist the relief aircraft coming out later. At 1435, CFC told me that the high-speed rescue launch F115 was proceeding from Dartmouth operating on guard frequency... the launch left Dartmouth at 1500 hours. The arrangement was that one aircraft should circle the dinghy and that another would lead the launch to the circling aircraft as the launch could not home on to it. The launch arrived and picked up the dinghy at 2205 hours. The launch took seven hours to reach the dinghy. The circling aircraft tried to contact the launch by wireless transmission and by visual signals from this time until 2313 hours but without results. The aircraft was recalled at this time period at 0715 hours April 5th, CFC informed us that the marine craft had arrived at Halifax with the dinghy containing the frozen body of an air man who was identified as Sergeant Keegan of the lost aircraft.”

The sixth witness, AC1 A. L. Crafton, 1463103, timekeeper, identified the crew that boarded Hudson FK541.

The seventh witness, F/O T. G. Mitchell, 50034, Ship Recognition and Tactics Officer stated that he briefed the crew of Hudson FK541 on April 1, 1944. “I think that in view of the fact that the crew organization seems to fall short of what is required when difficulties are encountered on operation training flights, pupil crews ought to be given more practice and experience before going on these flights. Particularly, I think they need more practical instructions on ditching.”

The eighth witness, F/L C. H. Napier, 116645, HQ Signals Officer stated, “I feel that more instruction should be given on the operation of dinghy radio. At all briefings, the use of 500 Kcs band in emergency is explained and emphasized and WAGs are instructed to tune their transmitters and receivers to 500 Kcs when crossing coast. The use of the 500 Kcs band for practice has been not yet clearly defined and it is felt that at least one practice message on this frequency should be sent by each aircraft while over the sea.”

The ninth witness, P/O E. W. Sherwood, J39812, Staff Instruction No. 2 Squadron, No. 31 O.T.U. Debert, stated that the procedure for instructing and practicing emergency ditching and the use of the dinghy was as follows: “A lecture is given to the course as a whole and dinghy procedure, and necessity of crewmembers knowing exactly what has to be done in the event of ditching. The dinghy radio is displayed in its use and operation is explained. Then they're taken individually by an instructor to the synthetic training where the crew go through ditching, dinghy procedure and drill. The crews practiced these two or three times and are timed to induce speed in getting out of the aircraft into the dinghy. No instruction is given with the dinghy on hand. My recommendations are that all equipment required for ditching should be in the synthetic trainer, including the dinghy radio, emergency rations, etc. Dinghy drill should be practiced in the water with the inflated dinghy, and if possible, from an aircraft in the water.”

The tenth witness, F/O H, Zumar 15395, Acting QC No. 3 Squadron, 31 O.T.U. Debert stated that he took part in the search for Hudson FK541. “The search was carried on by aircraft flying from base to Sable Island, from Sable Island to Sheet Harbour, from Sheet Harbour to Sable Island, and from Sable Island back to Base. I have been employed overseas in the sea rescue work for approximately one year. The most successful method of search was creeping line ahead, aircraft from 1/4 to half a mile apart, altitudes depending on whether and condition of the sea varying from 100 to 1000 feet. I have not piloted flying boats, but the condition of the sea was very calm with very little swell, and I believe a Canso would have been safe to have landed. Not having flown with P/O Horton, I cannot assess him or his crew but in my estimation his training up to the time of his last flight fully qualified him to undertake operational training flight Number 3. He was assessed as an average pilot with low average an instrument flying.”

The eleventh witness, F/O B. Gruenwald, J16975, Staff Pilot, No. 2 Squadron, 31 O.T.U. also took part in the search for Hudson FK541. “On the 4th of April 1944, I was detailed to pilot a Hudson and to relieve another aircraft in the picking up of the dinghy from Hudson FK 541. We arrived at the location around 2100 hours and in the course of 1/2 an hour or so we could see a minesweeper coming in the direction of the dinghy and presumed it to be the craft detailed to pick up the dinghy. As the minesweeper approached the dinghy, we got a visual signal from them to go onto R/T, which we did. The only answer we could get was from an unknown origin. Around 2200 hours, the minesweeper picked up the dinghy. We informed base and set course back to base. Just as we were setting course for base, we saw the rescue launch about two or three miles away from the location. We then received a message from base informing us to inform the launch to search the area for bodies. We could not get any W/T signals through to the launch and informed base accordingly. We were then informed by base to return to the launch to give them signals visually. We circled the launch several times and sent the signal several times but received no reply.”

The twelfth witness, WO1 C Nauffs, 1999, Master of Marine Craft M306 ‘Detector’ stated, “On Tuesday, April 4, 1944, at approximately 1410 hours, I received orders to stand by from OC Marine Squadron. 1445 departed base on orders to depart…First sighted aircraft at 1908 hours circling. At 2029 hour, picked up yellow funnel shaped object. I thought it was a smoke float….at 2120 hours, aircraft flew low…our course altered…following aircraft. At 2149 hours, W/T signal received from aircraft that a corvette had picked up the dinghy. At 2155 hours, Naval craft sighted ahead. At 2215 hours stopped and made fast alongside minesweeper ‘Drummondville’ commanded by Lt. H. C. Hatch. The crew of the Drummondville informed me that the dinghy contained a body and that they had just held the dinghy pending our arrival, at the request of the aircraft. At 2230 hours, departed for base. The position of the dinghy…was about 5 ½ miles southeast of the original position given. I was unable to contact EAC or base by W/T after 2000 hours. We received operations message, but we were unable to inform them of this...the return trip was uneventful. About 2230 hours as we left the mine sweeper, the aircraft circled us attempting to establish communication by Aldis Light. Because of difficulty in focusing, I was unable to read his message, whereupon he continued on his course for base. 0544 hours, Devils Island was abeam and I altered course up harbour entrance. At 0615, I cleared the examination vessel. At 0628, passed through gate. 0645 made fast at base. Telephone operations informing them that we had a body on board and asked them for an ambulance. At 1430 hours, coroner given verbal report on recovery of Sgt. Keegan’s body. I could have left earlier than 1445 hours. We received signals from the minesweeper about four miles from them signaling by Aldis lamp asking for identification. We replied with Naval identification number. They replied for us to close in on the port side. We covered the area twice and then returned to base as the captain of the minesweeper informed me that he had been in the area for some time and had not seen anything else. It was difficult in reading the Aldis lamp signals from the aircraft because I thought it was due to the fact that the aircraft was making two tight circles and consequently the wireless operator had difficulty in keeping the Aldis light focused on us. He was down to an altitude of about 500 feet and approximately a mile away. I was able to make out a few of the letters occasionally but due to the speed of the aircraft, the lamp would get out of focus. AC Nielsen E.G. was the W/T operator onboard. My regular wireless operator, LAC Boyd, was ashore at the Marine W/T section getting spare parts when I was ready to sail. The nearest available operator on the dock was detailed to make the trip with us. It was his first trip to sea. LAC Boyd had left the ship at 1330 hours which was 40 minutes prior to order to stand by, but it would have taken five minutes to get him to the boat. The cruising speed for this boat was 18 knots. We averaged 16.5. The dinghy was in 1/2 inflated condition so that the edges of the dinghy folded in over the body thereby preventing the body from being seen by the aircraft. Alongside of the body was a parachute harness and two distress flares. The condition of the sea at that time was such that it would have permitted the landing of a Canso, I believe.”

The Senior Medical Officer, W/C J. D. Colquhoun, C4023, was the thirteenth witness and stated that “on the 5th of April 1944, a body was brought into this hospital at approximately 0700 hours. From identification discs, bracelet, and cards, the body was identified as that of Sergeant Keegan. A superficial examination of the body was made by me. The body was partially frozen in the clothing soaked with water and ice and somewhat discolored from the dye from the life jacket and other clothing. The face was very livid in colour and no surface injuries were noted except evidence of a bruise on the right side of the forehead, approximately 2 inches in diameter. I then contacted Debert and confirmed through a senior medical officer that this body was one member of a crew missing from that station. A post-mortem examination was requested by No. 31 O.T.U. and I contacted the coroner, E. L. Cote, Dartmouth, and completed the arrangements for the post-mortem to be performed by Doctor Ralph P. Smith, provincial pathologist. A verbal statement has been received by me from Doctor Ralph P. Smith to the effect that Sergeant Keegan died from drowning and in his opinion this occurred approximately 6 hours after his last meal. Doctor Smith reported that there were no injuries, internal or external other than a few superficial scratches and a bruise on the right side of his forehead. A carbon monoxide test was not made.”

The fourteenth witness, AC E. G. Nielsen, R185977, WO, stated that he was detailed to go as wireless operator on Marine Craft M306 on April 4, 1944. “At 1935 hours, master of marine craft gave me another signal to send on the effect that an aircraft had been sighted. I did not succeed in getting that out. Throughout the afternoon and evening, Eastern Air Command tried to get me but they could not hear me for this reason they did not send the message. Hudson 562 called me up on the guard frequency RT telling me that a Corvette had just picked up the dinghy at 2145 hours.” He explained that he was not able to contact the wharf at base because his transmittion had drifted slightly off frequency. He tried both W/T and R/T. “This boat is equipped with a poor set of batteries and they run down quickly. There was a good deal of interference and after we got out 50 miles, my signals gradually became weaker although I could hear base and Eastern Air Command all right. I did not hear Hudson 562 calling me after 2200 hours because I had switched from their frequency to night guard frequency. I commenced getting seasick after turning back to base. However, I carried on with my duties.”

The fifteenth witness, F/L J. P. McCall, J8337, Flying Control Officer, stated “that all dinghies in the aircraft of this unit are periodically inspected every 100 hours and on the occasion of a major inspection of the aircraft. CO2 bottles are weighed, and the operating head checked every 50 hours. Beginning at 10:20 hours, and throughout the day, 11 Hudsons from this unit took part in the search, the total flying time of 49:10 hours. The method of the search followed parallel track from visibility half mile in area assigned.”

The sixteenth witness, F/L G. M. Ward, C8535, Senior Flying Control Officer outlined the procedure for what occurred when Hudson FK541 was reported missing. He said that the Navy were requested to ask ships in the area of any news of the aircraft, fearing that the rescue launch might not reach the dinghy before dark. A boat was despatched from the convoy to pick up the dinghy. “The only explanation that I can give about having no radar plots of the missing aircraft is to say that either the aircraft was flying too low to be picked up by radar station or was flying during part or all of its track through one of the blind spots. Consideration was given to send out a Canso, l but it was considered too risky in view of the fact that the dinghy had been reported empty. All stations asked to cooperate in this search were advised to have their aircraft fly at 500 feet height and 3/4 of a mile visibility. On April 2, from Debert there were 14 Hudsons, from Dartmouth there were two Venturas, and one aircraft from Sydney for a total of 17 aircraft and 62 hours flown. On April 3, from Debert, 4 Hudsons, Sydney, 3 Venturas for a total of seven aircraft and 10 ½ hours flown. On April 4, one aircraft from Sydney for four hours. Weather was foggy on April 3. Above does not include hours flown in connection with the dinghy. Because of the finding of the dinghy, Debert decided to cancel further search after April 4.”

The final witness, F/L C. C. Underhill, J5112, produced the photograph of the dinghy in the water taken from one of the aircraft.

A post-mortem performed on the body indicated that Sgt. Keegan had died of drowning approximately six hours after his last meal. “CAUSE: Obscure. RECOMMENDATIONS: At this Unit, dinghy practice more closely resembling actuality. More instruction on the operation of the dinghy radio. Sending of practice messages on 500 Kcs frequency by WAGs. In every case where it is possible, the use of creeping line ahead a/c searching plan a set out by 10th witness. The number of missing a/c in EAC has averaged about one every six weeks during the past year. In the majority of flights, the crew were students and practically all cases have one characteristic in common: a lack of signals. The thing that would count most in reducing the frequency of this type of accident would be giving the crew, particularly the WAGs, more practice and experience by means of briefer flights before going on flights of an operational nature over water. If, in order to do this, it would be necessary to lengthen the time of the present course it is recommended that such be done. REMARKS by CO: I concur and steps have been taken to carry out the recommendations…if it is possibly for WAGs to carry out night operating practice at their wireless schools (which they do not do at present) it would obviate the necessity of increasing the training of WAGs at O.T.U.s. CONCLUSIONS OF AIB: Agree with findings and recommendations.”

In a memo from S/L G. A. P. Brickenden, Flying Accident Investigation Officer, EAC, Halifax noted that WAG Sgt. Keegan was found between Dartmouth and Sable Island, about 45 minutes flying time from base. The report of the autopsy performed at Zinck’s Undertaking Rooms, Dartmouth on April 5, 1944 at 3:30 pm at the request of S/L J. A. Mahoney, EAC: “GENERAL APPEARANCE AND MARKS OF EXTERNAL VIOLENCE: The body is that of a white male of sturdy build and about 20-25 years of age. Over the face and legs and part of the body is a greenish-yellow dye, possibly derived from the deceased’s boots. There is a bruise over and to the lateral aspect of the right eye with a small laceration. The face and lips have a dusky reddish colour and the tongue extends to the margin of the teeth. There is some post-mortem lividity on the back of the upper part of the shoulders. The eyes are congested and have a greyish glazed character. There are some small abrasions on the back of the left and over the knuckles of the right hand. The fingers of both hands are clenched and rigor mortis is still present in them though it has largely passed off in the rest of the body. On the left leg are three small abrasions about 1/2” long at the knee over the patella and a small abrasion about the middle of the Tibia anteriorly. The right leg shows an abrasion, 3” long, on the lateral aspect of the upper part of the thigh, a small one on the lateral aspect of the knee and on the knee itself as well as another small one over the middle of the tibia anteriorly. The skin on the hands and feet is pale, bleached, wrinkled and somewhat sodden. The penis and scrotum are retracted to some extent. The ribs and bones generally reveal no evidence of fracture. INTERNAL EXAMINATION: Trachea and bronchi: contain a whitish frothy fluid and are somewhat red and congested. The pleural sacs: Right: contains about 1 ½ pints of a clear watery fluid. Left: contains about 1 pint of a similar watery fluid. The Lungs: are voluminous and bulged on removal of the sternum. They …both…have a spongy sodden feeling. Superficial petechiae are seen. On section they are congested to some extent and a watery blood and frothy fluid poured from them on pressure even from the minute bronchioles.” Keegan’s major organs were also looked at. “Only a small quantity of water had been swallowed shortly before death.” His skull showed no sign of fracture; his brain showed a small superficial haemorrhage. His lungs were congested as was his brain. “Heart-failure cells” were seen in the lungs’ lumens.” CONCLUSIONS: CAUSE OF DEATH: is obvious drowning, possibly aided to a certain extent by exposure. The marks of external violence and the small superficial haemorrhage in the pia-arachnoid over the left side of the vertex of the brain are not sufficient in themselves to have caused death but along with exhaustion may have induced a temporary lapse of consciousness, during with the head became submerged in the water in the rubber raft or dinghy and drowning ensued. The question as to the time of death is a difficult one to determine with any degree of accuracy, but the presence of the partially digested potato in the stomach contents would point to death having taken place not more than about six hours after a meal, in which potato had been taken. This could be checked. The condition of the face which is the earliest part of the body to undergo putrification in cases of drowning and the fact that water had transuded through the visceral pleura into both pleural sacs, which is a post-mortem change and takes two or three days to occur, would point to death having elapsed sometime before the autopsy was performed. This I reckon to have been not less than three and possibly not more than five days previously. A fair average would be four days. In consequence, as far as I can determine death took place sometime between Saturday evening, April 1, 1944 and very early Sunday morning, April 2, 1944.” Dr. Ralph P. Smith, MD, DPE, Provincial Pathologist

Keegan’s body was returned home to Montreal and was buried at Cimetiere Notre-Dame-des Neiges.

An article in the Halifax Chronicle, dated April 3, 1944: “A twin engine R.C.A.F. believed to be carrying four men has been missing since Saturday night on a flight from the Air Station at Debert Camp, Nova Scotia. The RCAF broadcast a radio appeal yesterday for residents to keep a lookout for the machine, which is said to may have been forced down in a triangle formed by Halifax, Debert, and Sheet Harbor, about 30 miles apart. Possibility was held also the plane may have been forced down at sea, and the RCAF air sea rescue service was combing the Atlantic in this vicinity for traces of the aircraft. The plane which was on a routine flight, had gasoline enough to last only until 7:00 o'clock Sunday morning. Next of kin of those aboard have been advised and their names will be announced later.”

On May 3, 1944, G/C F. S. Wilkins, Chief Investigator at the Accident Investigations Branch, stated, “A list of aircraft missing from No. 31 O.T.U, Debert, Nova Scotia during operational training night flights for the year ending 31 March 1944:

May 14, 1943: Hudson VI FK468, 4 crew, time of take-off: 2135; last heard from: 22:45 June 5, 1943: Hudson VI FK409, 5 crew, time of take-off: 0232; last heard from: 0325 August 28, 1943: Hudson VI EW873, 4 crew, time of take-off: 0112; last heard from: 0210 October 30, 1943: Hudson VI FK443, 4 crew, time of take-off: 1743; last heard from 2015 January 29, 1944: Hudson VI FK547, 4 crew, time of take-off: 0344; last heard from 0426 February 21, 1944: Hudson V AM729, [4 crew], time of take-off: 0004; last heard from 0015

In all the above cases, the aircraft was manned by a student crew. Although it may have no significance, it is somewhat remarkable that in only one case, that of the 30th October 1943, had the aircraft been airborne for much more than an hour. For the 2nd, 5th, and 6th accident in the list, the last signal heard from the aircraft was that they were changing to D/F frequency. In the first accident, the last signal was a position report at the second turning point; while in the fourth, the last signal was an OK acknowledgement. In only the last three accident mentioned above, weather conditions might have affected the flight.”

Memo, dated May 18, 1944: INVESTIGATION INTO MISSING HUDSON VI FK541, No. 31 O.T.U. “the following comments are made in connection with the above accident: 1. All crew drills are designed to resemble the real thing as close as possible. In this respect, local conditions and the availability of equipment have a serious bearing. Remarks by the Commanding Officer show that action is already being taken on this recommendation. 2. If properly carried out, the present lectures, demonstrations and handling of the dinghy radio are considered sufficient to enable the crew to efficiently operate the dinghy radio in an emergency. Again, it is noted from the Commanding Officer's remarks that action is already being taken on this recommendation. 3. It is pointed out that 500 Kcs is the International Distress Frequency. As the picking up of any message, no matter how short, on this frequency, will set into operations rescue procedure, a new account must this be compromised by practice. Instruction is given on the setting up of other frequencies and the emergency procedures on them. The operation of tuning to the 500 Kcs frequency is no different to tuning to any other. In this respect, it is pointed out that the dinghy radio is preset on this frequency, so that it's actually used in training is limited. 4. No recommendation is made here because final responsibility must be left with those regarding the search… 5. The evidence pointing to the aircraft having crashed shortly after its last transmission and that the lack of signals was due to this fact. The question of giving wireless operators/air gunners more practice is being taken up separately. 6. In the list of accidents appended by C. I. A., the indications are that two-way wireless contact has been established, that the exercises were being proceeded with and that through lack of evidence, there is nothing to show that the signals training has any bearings either way in any of these. In point of fact, the establishing of contact serves only to indicate that the operators were sufficiently trained. However, this is being taken up.” AVM A. de Niverville, AMT

Memo, dated May 31, 1944: INVESTIGATION INTO MISSING HUDSON VI FK541, No. 31 O.T.U.: 1. Reference is made to the recordings submitted in above connection and the following observations made: (a) “In the majority of flights, the crews were students and practically all these cases have one characteristic in common, a lack of signals.” (b) The position at which the dinghy was found was relatively close to the estimated position of the aircraft at the time it was last heard from” 2. Commenting on the above, the two appear irreconcilable. Assuming that the aircraft crashed shortly after transmission of the position report, it would appear that the cause of lack of signals was the destruction of the aircraft through some reason unknown, and all evidence supports the theory that the wireless transmission communication was established up until, at the most, a matter of minutes before the aircraft crashed. 3. It is pointed out that 500 Kcs is the International Distress Frequency. As such, its use is to be limited to actual high priority distress signals only and practice on that frequency cannot, therefore be considered. 500 Kcs presents no abnormal difficulties to the operator with experience in M/F operation. If practice on the liaison set is considered necessary, it should be done on a suitable medium frequency, but in no circumstances on the distress band. As far as the dinghy radio is concerned, the transmitter requires no tuning other than aerial leading, being preset by the manufacturer at 500 Kcs. Practice on the handling of this set, as a feature of ground training, is permissible providing that radiation of signals is limited by substitution of an artificial aerial for the normal antenna. 4. The majority of signals briefing appears to have been given by the ship recognition and tactics officer acting as navigation officer. Liaison must be made before briefing between navigation and signals officers in order to correlate their briefs, in no circumstances should the signals brief be given by any person other than the duty signals officer or the signals instructors appointed by the senior signals officer. In this particular case the signals briefing delivered by Flying Officer Mitchell seems conflicting as the following extracts will illustrate: ‘W/T Contact must be made with base every half hour’. ‘If W/T contact is not made at the end of one hour, go over to EAC frequency. If contact is not made at the end of an additional half hour…’ 5. It is emphasized that lack of satisfactory two-way signals communications must necessitate the earliest possible return to base of the aircraft or landing at another suitable airfield. For this purpose, a positive time limit for absence of such communications must be established and pending the issue of irrelevant order in the matter the following should be observed by O.T.Us. Satisfactory two-way communication is to be established at every half hour period of the flight. Any failure in such compliance is to be immediately reported by the wireless operator or NAV to the captain of the aircraft. The operator is to endeavour to re-establish satisfactory two-way communications with base and or commands; if he fails to do so within a further 15 minutes, he is to report according to the aircraft captain, who is to immediately return to base or another suitable airfield. 6. Statement by 14th witness: the operator was able to receive signals from Eastern Air Command throughout the trip and it is not understood why he did not correct his transmitter frequency by back-tuning transmitter to receiver. This witness states that ‘throughout the afternoon and evening Eastern Air Command tried to get me but they could not hear me, for this reason they did not send the message’ commenting on this point, it is not understood why in the absence of reception of the marine craft signals, Eastern Air Command did not broadcast the message. This is standard procedure and had it been applied in this case, would have served a useful purpose.”

Memo dated June 13, 1944: “With reference to the recommendation (a) of the findings of the investigation on page 2, as regards this accident particular the pilot’s hours on Hudson’s indicate that this crew was more than 3/4 of the way through the course. This means that briefer flights than the one concerned would have already been made by them for practice and experience as laid down in the syllabus. It will also be noticed that the 4th witness says that this crew had previously completed by day, an identical exercise to the one in which they crashed, for which they had received an above average rating. There is little doubt, therefore, that they should have been at a sufficiently advanced stage of trading to be said on this exercise. It is felt however that in general the wireless air gunners lack air practice time before they go to operational training units, and I happen to be reviewing their training at this moment with the object of remedying this.” AVM A. de Niverville, AMT

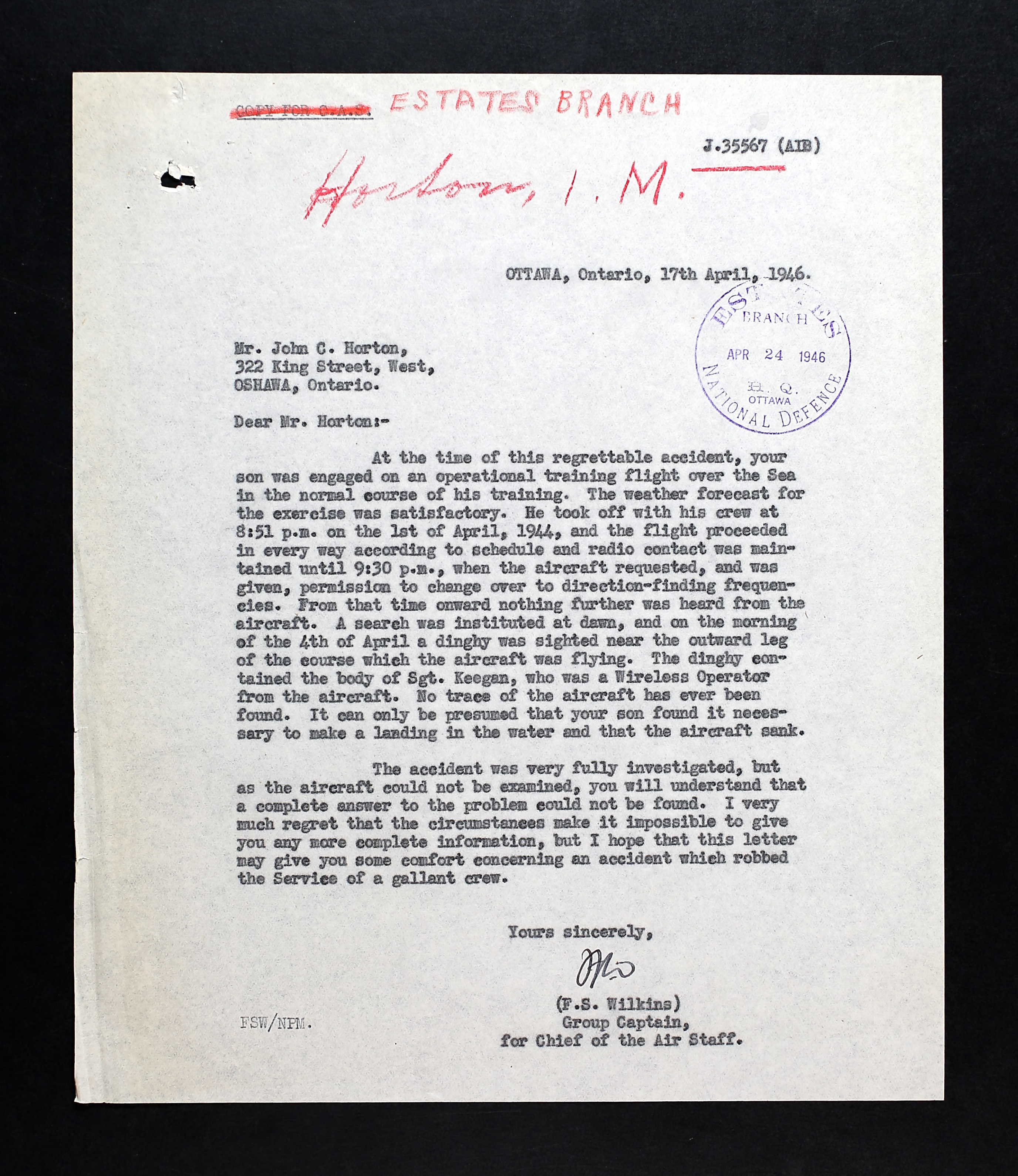

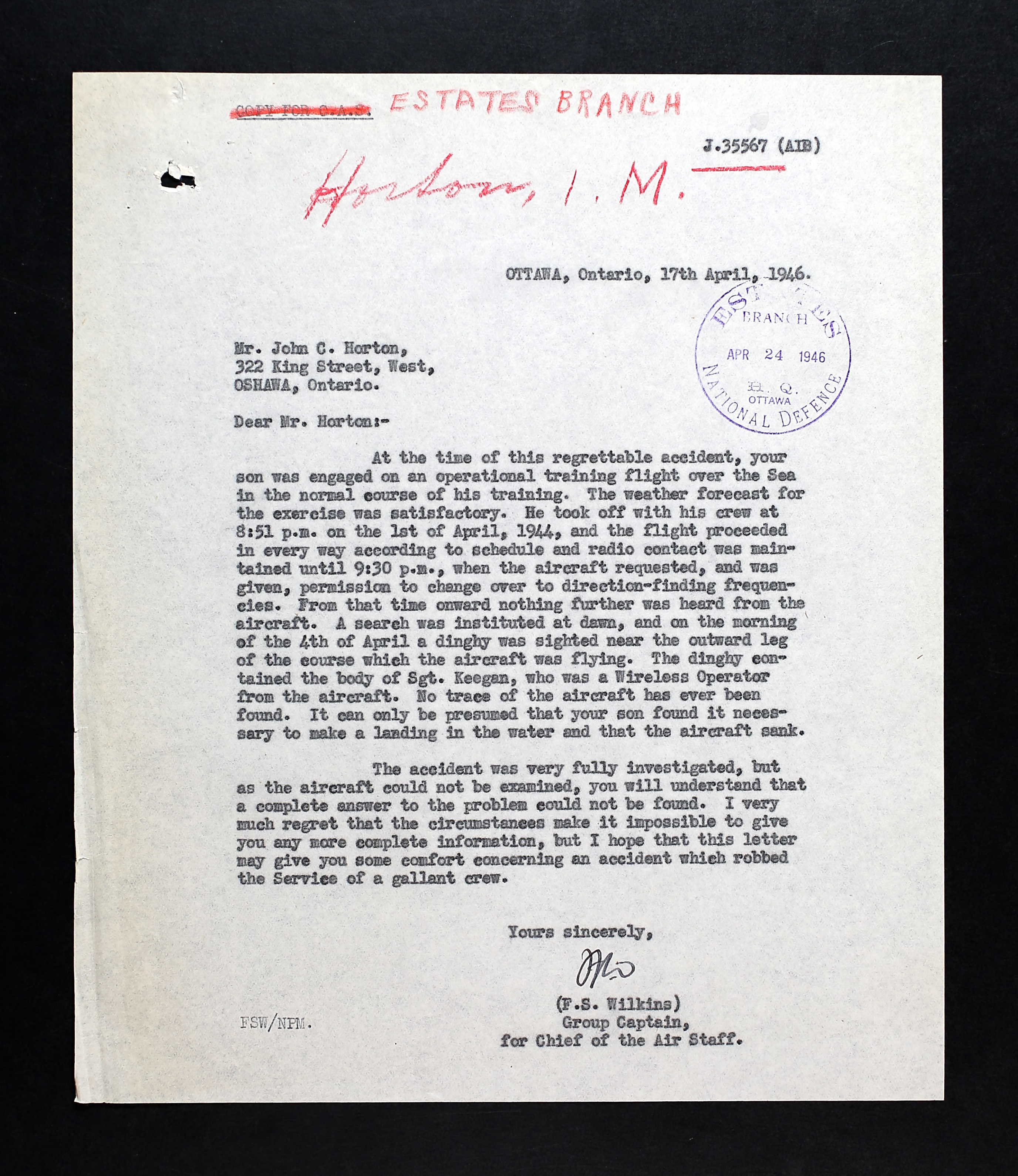

A letter written by G/C F. S. Wilkins, arrived at Mr. Horton’s residence in Oshawa mid-April 1946. “At the time of this regrettable accident, your son was engaged on an operational training flight over the sea in the normal course of his training. The weather forecast for the exercise was satisfactory. He took off with his crew at 8:51 PM on the 1st of April 1944 and the flight proceeded in every way according to schedule and radio contact was maintained until 9:30 PM when the aircraft requested and was given, permission to change over to direction finding frequencies period from that time onward nothing further was heard from the aircraft. A search was instituted at dawn, and on the morning of the 4th of April, a dinghy was sighted near the outward leg of the course which the aircraft was flying. The dinghy contained the body of Sergeant Keegan, who was a wireless operator from the aircraft. No trace of the aircraft has ever been found. It can only be presumed that your son found it necessary to make a landing in the water and that the aircraft sank. The accident was very fully investigated, but as the aircraft could not be examined, you will understand that a complete answer to the problem could not be found. I very much regret that the circumstances make it impossible to give you any more complete information, but I hope that this letter may give you some comfort concerning an accident which robbed the service of a gallant crew.”

In late October 1955, Mr. Horton received a letter informing him that since Ian had no known grave, his name would appear on the Ottawa Memorial.