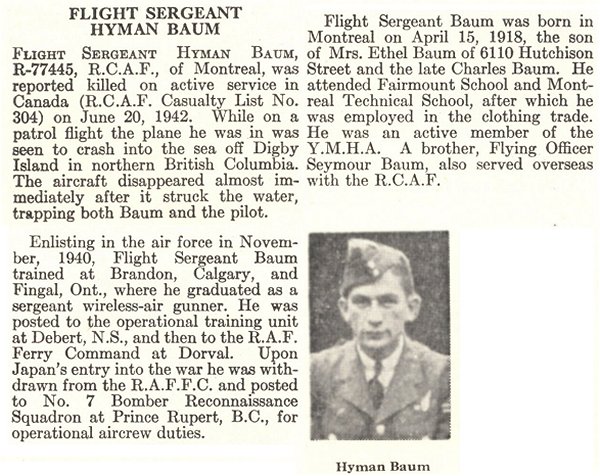

April 15, 1918 - June 20, 1942

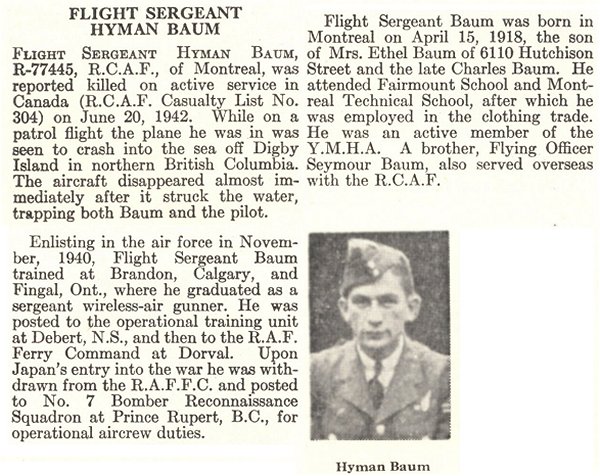

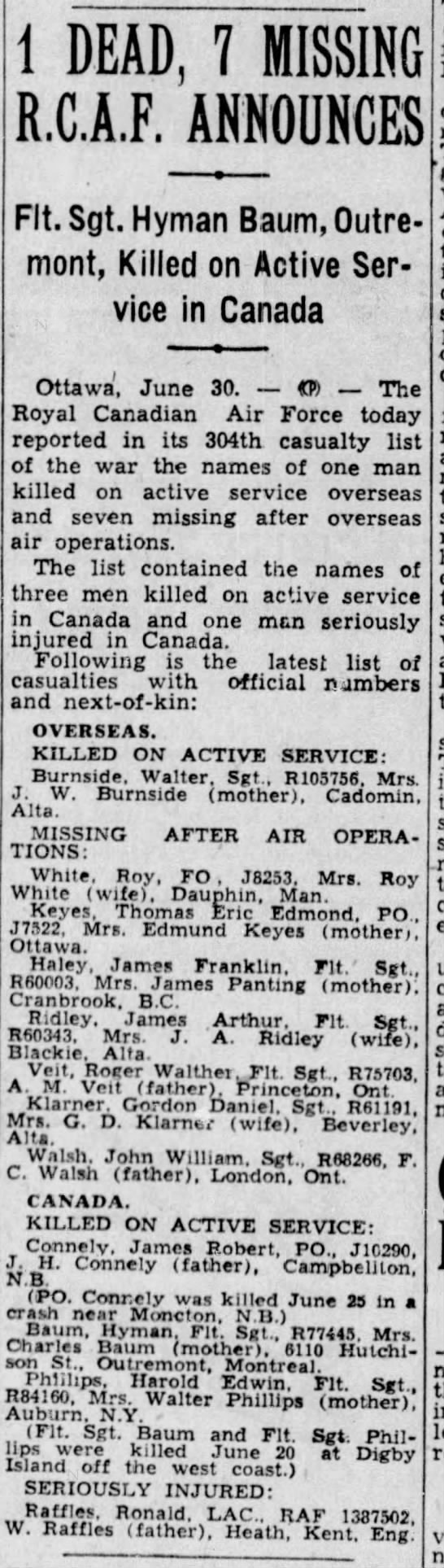

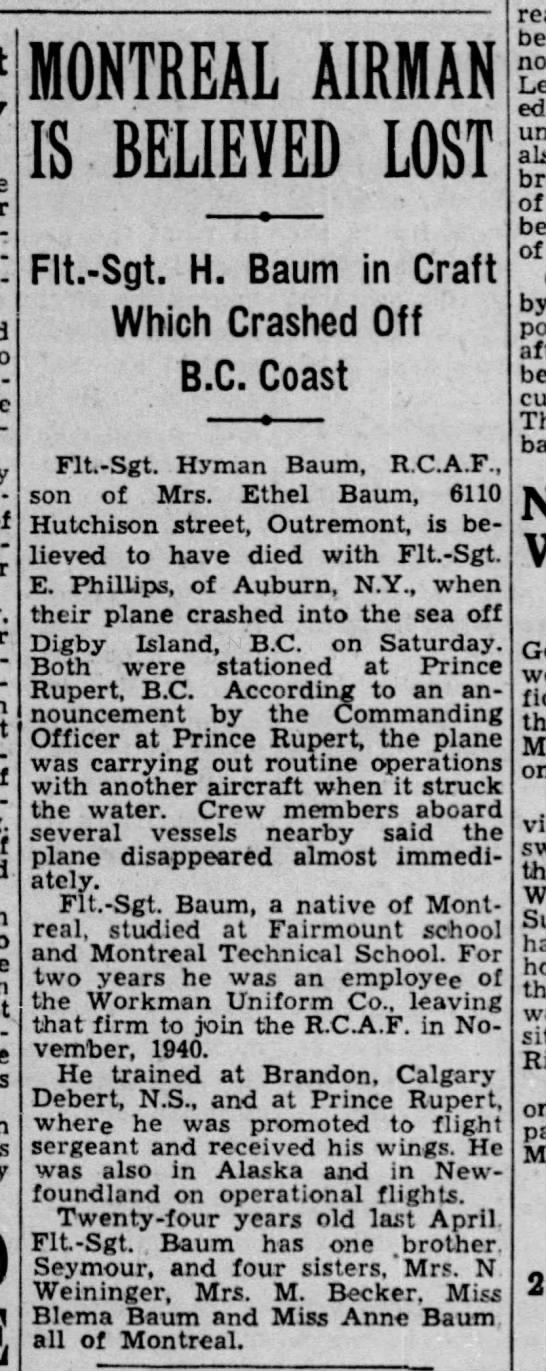

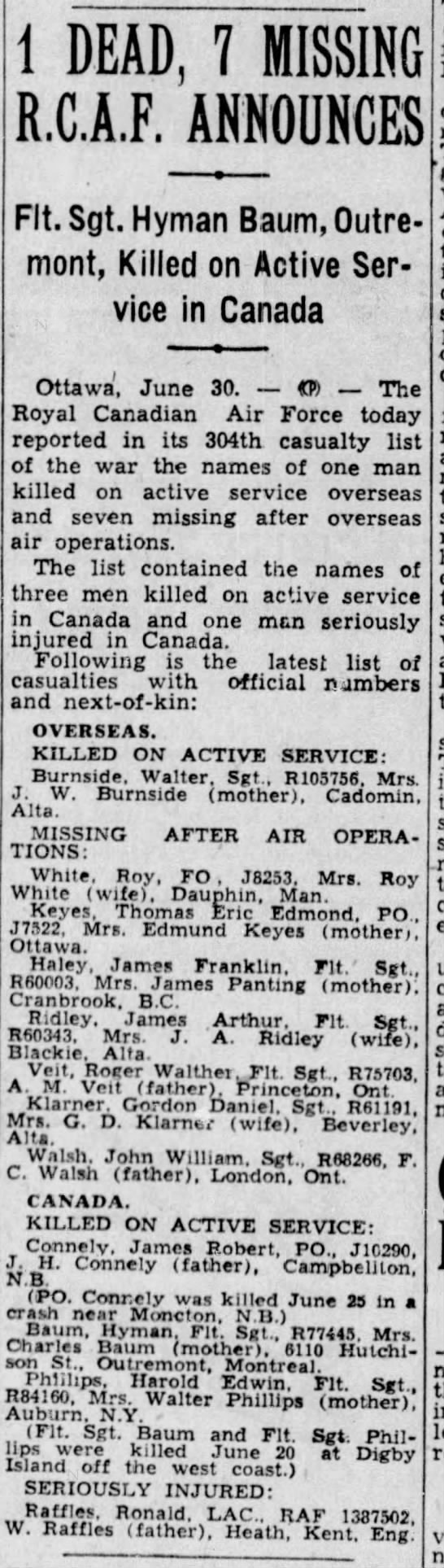

Hyman Baum was the son of Charles (Zelig) Baum (d. 1941), jeweler, and Ethel (Etty) (nee Levitt) Baum (d. 1984). He had one brother, Seymour (d. 1987), who also joined the RCAF (Service No. R164736), and four sisters, Mrs. Ella Weininger, Mrs. Ida Becker, Mrs. Annette Katz (1913-2001), and Blema Baum. They resided in Montreal. The family was Jewish. (Hyman’s parents were both born in Russia, marrying in 1907 in New York City.)

Hyman had two years’ high school and attended night (tech) school for one year, earning a scholarship in mechanical engineering. He spoke English and Hebrew fluently.

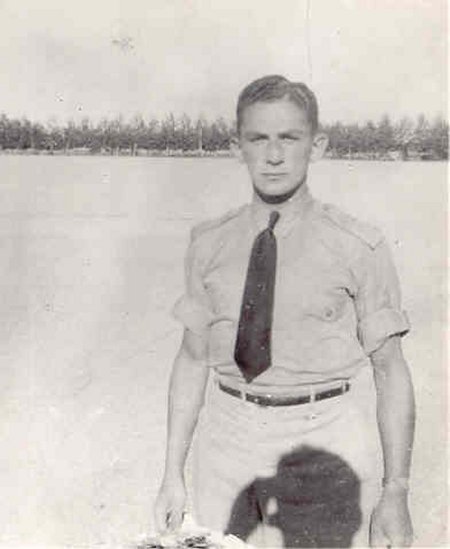

He liked to swim, ski, played tennis, bowled, and rode horses occasionally.

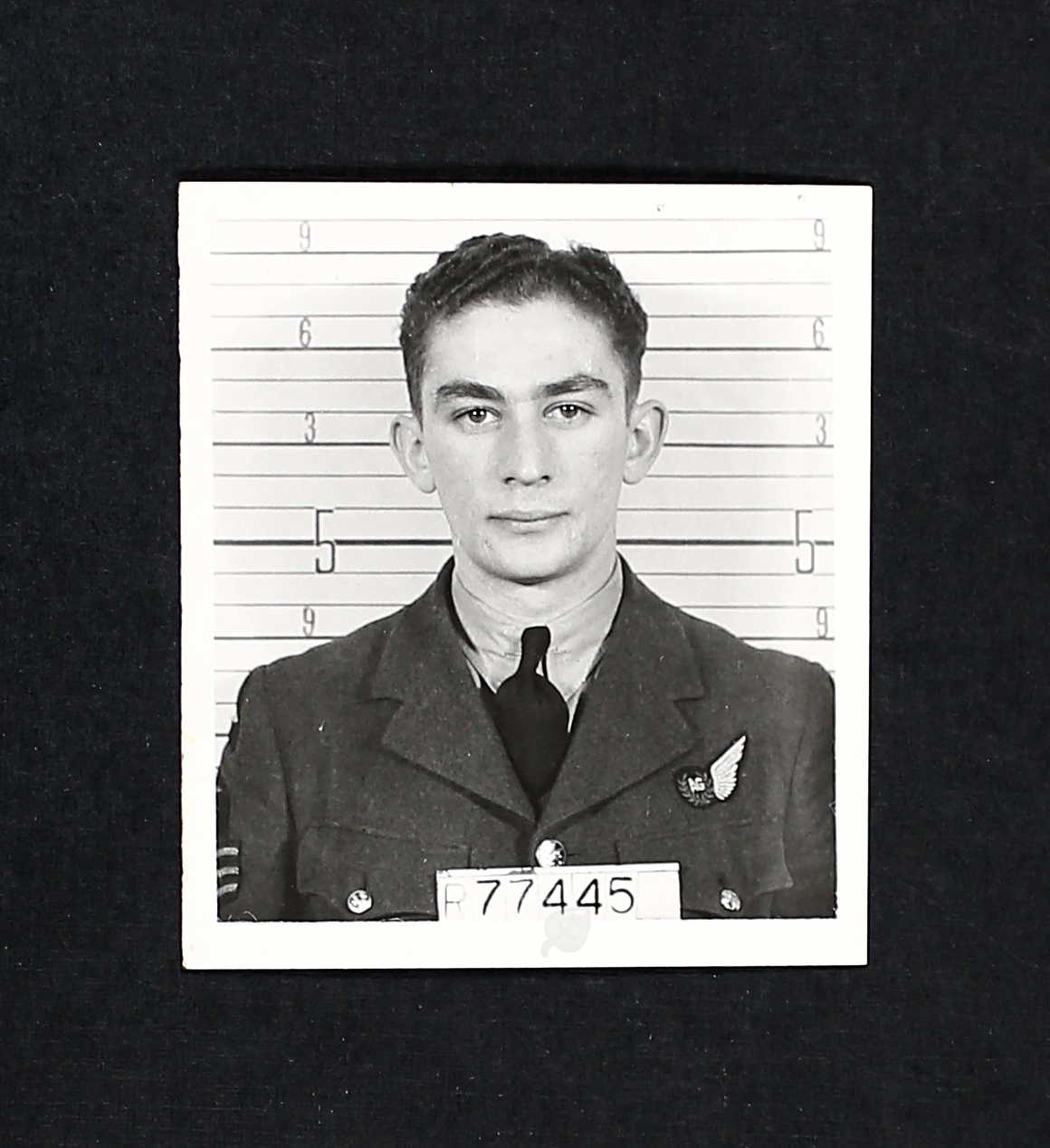

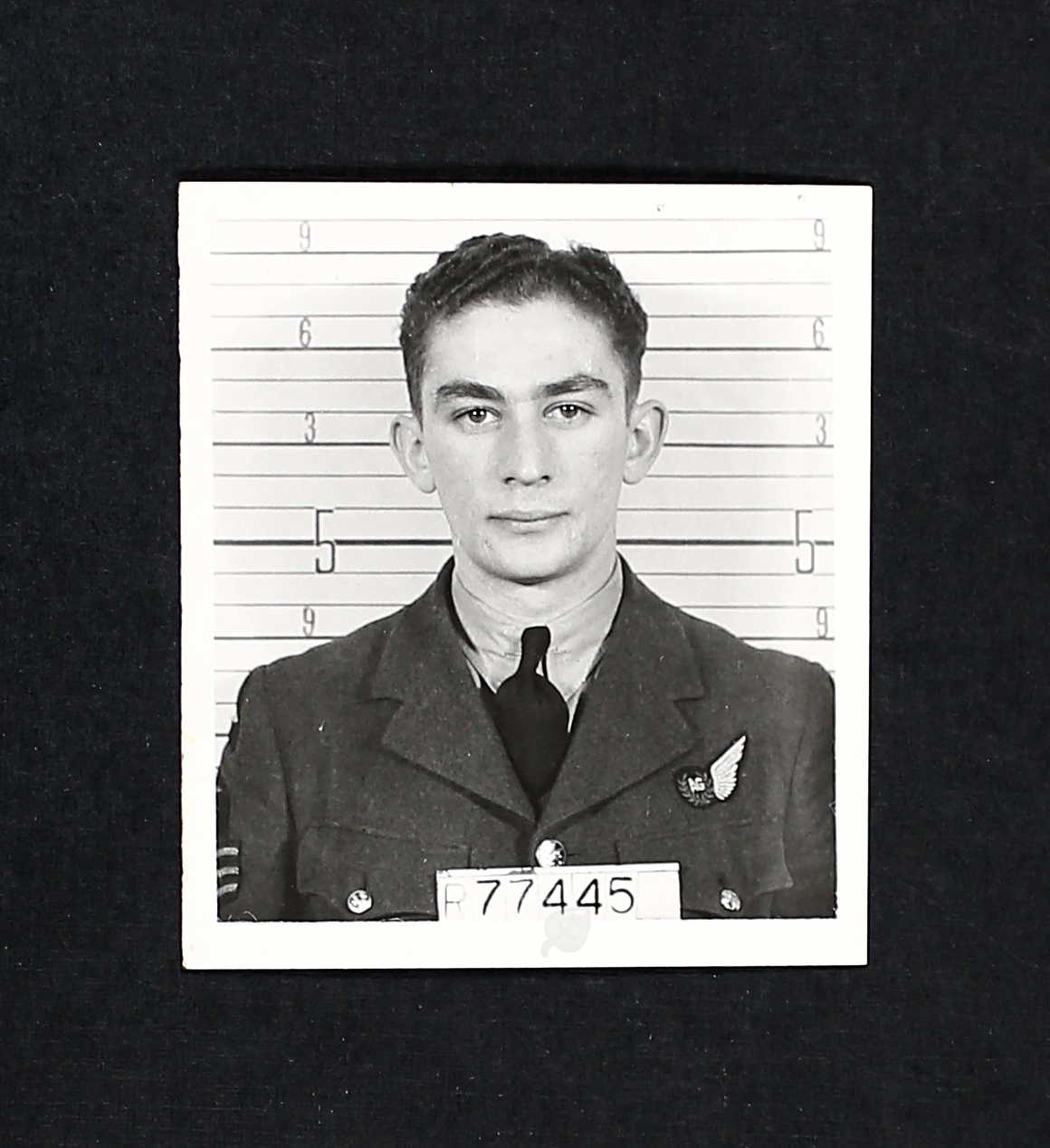

He was employed by Mr. L. Rubenstein, clothing contractor, as a machine cutter, in Montreal, when he applied to the RCAF on September 28, 1940. After the war, Hyman hoped to remain in the RCAF -- mechanical or radio engineering. He had an old scar on his right leg and right arm, plus right elbow. He stood 5’7” tall and weighed 145 pounds. He had brown eyes and black hair. “Average type, fair education, neat in appearance, anxious to serve. Best fitted for Gunner.”

“Excellent type. Good cardio-respiratory efficiency.” On November 20, 1940: “His father states that candidate faints frequently for trivial or no reasons. Candidate denies this; says he fainted two or three times up to the age of 12 after cutting himself, etc., but that he has not fainted since except on one occasion. This was while in hospital at NPAM Can. Militia T. C. No. 40…when he tried to walk across the ward after being in bed several days. Circulatory reflexes today are satisfactory.” On November 25, 1940: “Candidate is very keen to join. Has had upper respiratory infection since previous exam but tests are normal today.”

Hyman smoked ten cigarettes per day and indicated he very seldom drank alcohol.

He started his journey through the BCATP at No. 2 Manning Depot, Brandon, Manitoba on November 27, 1940. On December 21, 1940, he was taken on strength at No. 2 Wireless School, Calgary, Alberta until July 18, 1941. “75.3%, Pass. 44th out of 209 in class.”

From Calgary, he was sent to No. 4 Bomb and Gunnery School at Fingal, Ontario until August 19, 1941, where he was given his Air Gunner’s Badge. “Air Training: 1st in class of 33. Pass. His marks have been fairly high at this school and he seems capable and keen on his work, but he is not outstanding.” Final assessment: “7th out of 33. 76.3%. Above average.”

Hyman was sent to Y Depot, Halifax August 10, 1940, then to No. 31 O.T.U. Debert, Nova Scotia until December 13, 1941. “Above average. 78%. 7th out of 22 in class. Hard working, conscientious and intelligent, he will do well. Very dependable in emergency.” In Armament Training: “Due to lack of training equipment and training facilities, this gunner has had very little experience with the Boulton and Paul turret and twin Browning guns. Shows promise with the little experience obtained. Intensive training in the above is absolutely essential before despatching on operational flying since the only training received in air gunnery prior to arrival on this Unit was from Fairey Battle aircraft equipped with VGO Gun only. 71.5%. 6th out of 22 in class. Confident and conscientious. Quite good material.”

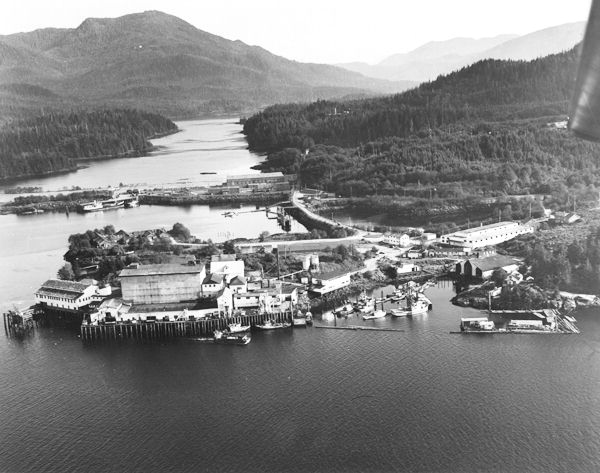

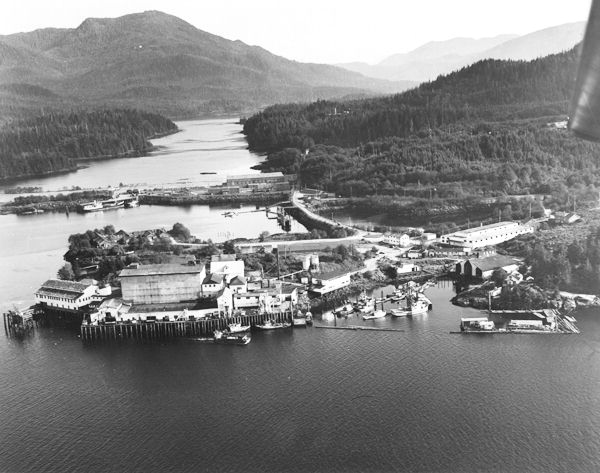

Traveling across Canada, he found himself at Western Air Command in Victoria, then with No. 7 (BR) Squadron Prince Rupert, BC. He ventured to Patricia Bay and No. 32 O.T.U. in May 1942, then returned to Prince Rupert. When he was being considered for a promotion to Flight Sergeant, in February 1942, Hyman scored in the mid-80s. “A particularly good NCO.” His final mark was 83%.

On June 16, 1942: “Neat, pleasant personality, good intelligence. This NCO has proven himself being keen, reliable, efficient, of good appearance.”

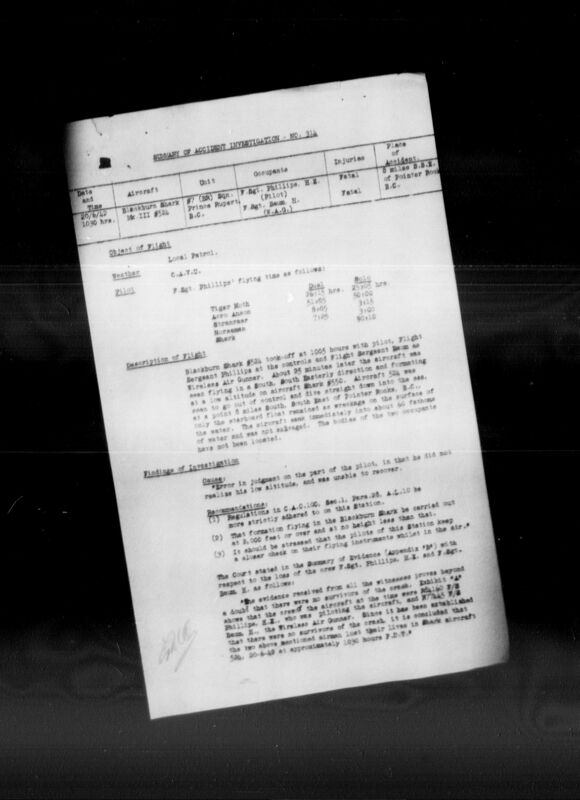

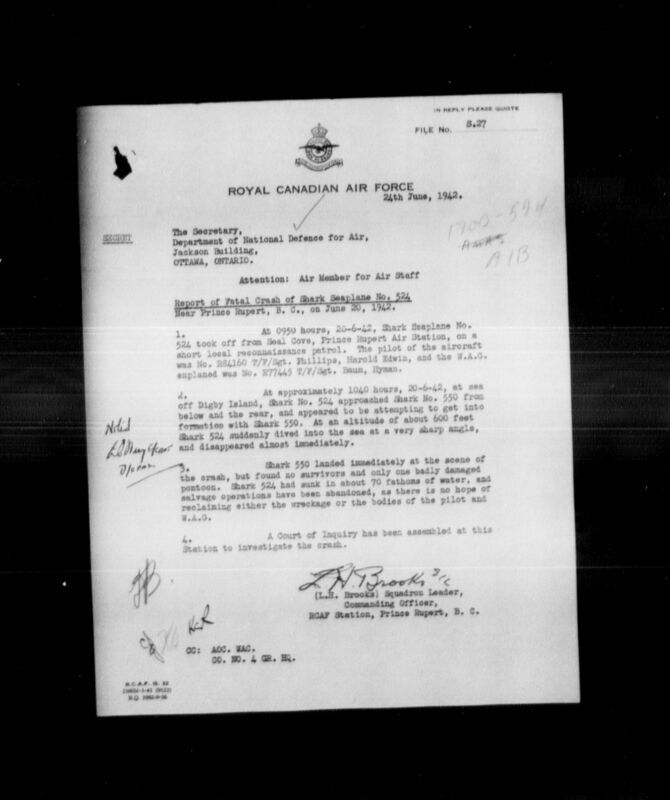

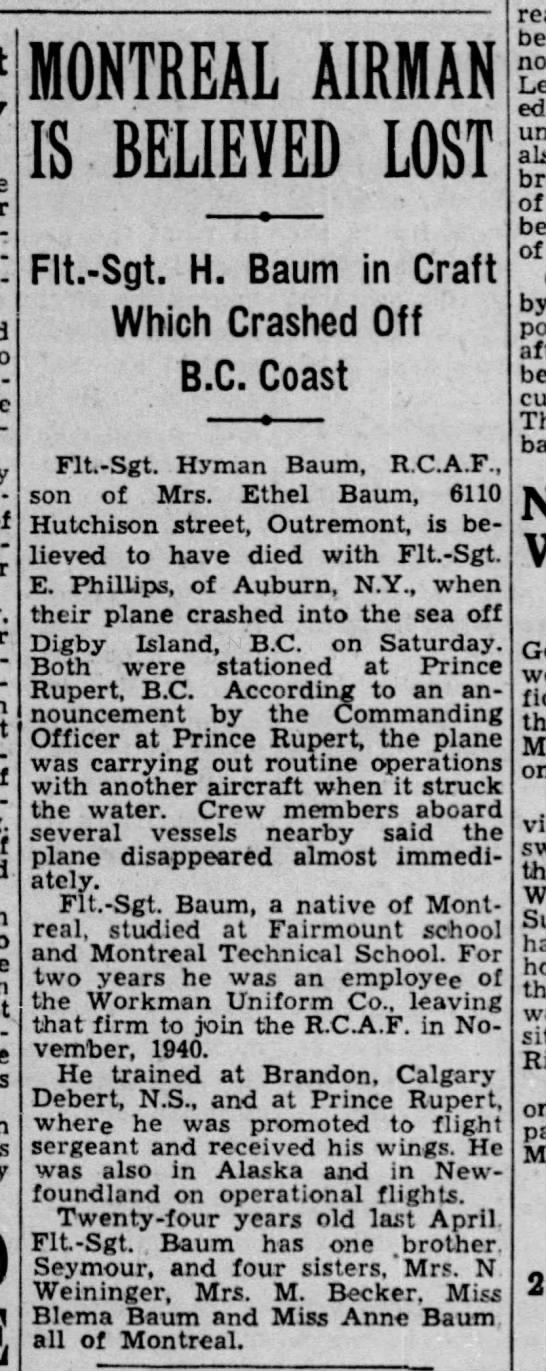

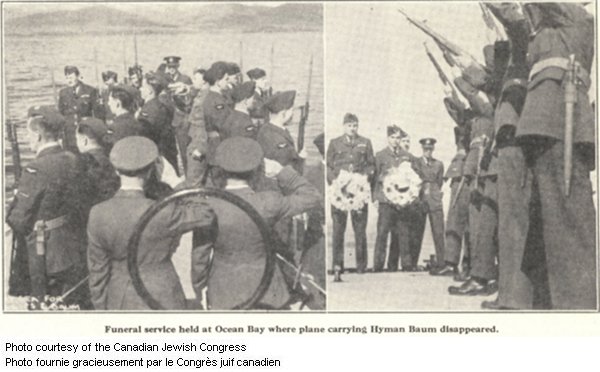

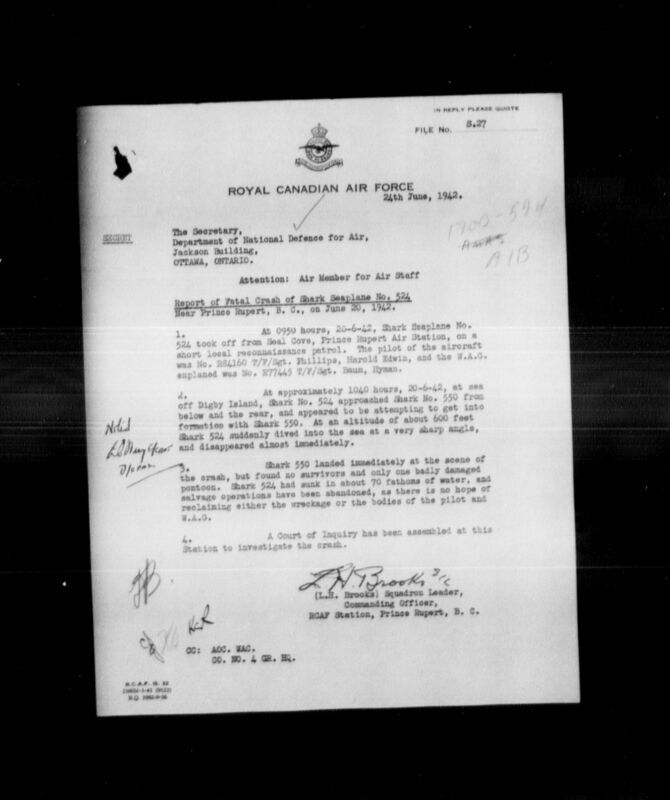

On June 20, 1942, near Prince Rupert, British Columbia, eight miles SSE of Pointer Rocks, Blackburn Shark MK III 524 crashed at approximately 1040 hours. He was the WOAG aboard the aircraft. He and his pilot, F/S H. E. Phillips, were on a routine patrol at the time. Neither the bodies nor the aircraft were recovered.

A Court of Inquiry was struck.

Flying Officer Peter Hamilton Gault, J3462, Bomber Reconnaissance Pilot, Acting Officer Commanding No. 7 (BR) Squadron, Prince Rupert, BC stated: “I was in the office at approximately 1100 hours when Flight Sergeant William Adolphus Holbeck called me from the Marine Section reporting the crash of an aircraft presumably Blackburn Shark 524. He said that he had advised the hospital ship and the crash boat, giving them the approximate position. I told him to report it to the Operations Room and to the Commanding Officer. I had the photographer and F/S Olson get into Blackburn Shark 550. We proceeded to the scene of the crash to see if we could be of any assistance in spotting floating debris from the air. After circling the minesweeper ‘Courtney,’ we landed beside it and asked if we could be of any assistance. They said, ‘No.’ I took off again and circled the area where the Navy tenders were operating. We did not see anything. I again landed and they told me to look for an oil slick or any signs of the aircraft. I took off again and stayed in the location for approximately 1 hour period then seeing no signs or indications of the crashed aircraft, I returned to Seal Cove, British Columbia at approximately 1330 hours.” He told the Court that two-250 pound bomb anti-submarine bombs or 500 pounds of bombs in all were aboard Shark 524. “I authorized for a local patrol within a radius of 25 miles from Seal Cove, BC and for one hour’s duration. The accident occurred approximately 15 miles from Seal Cove, BC.”

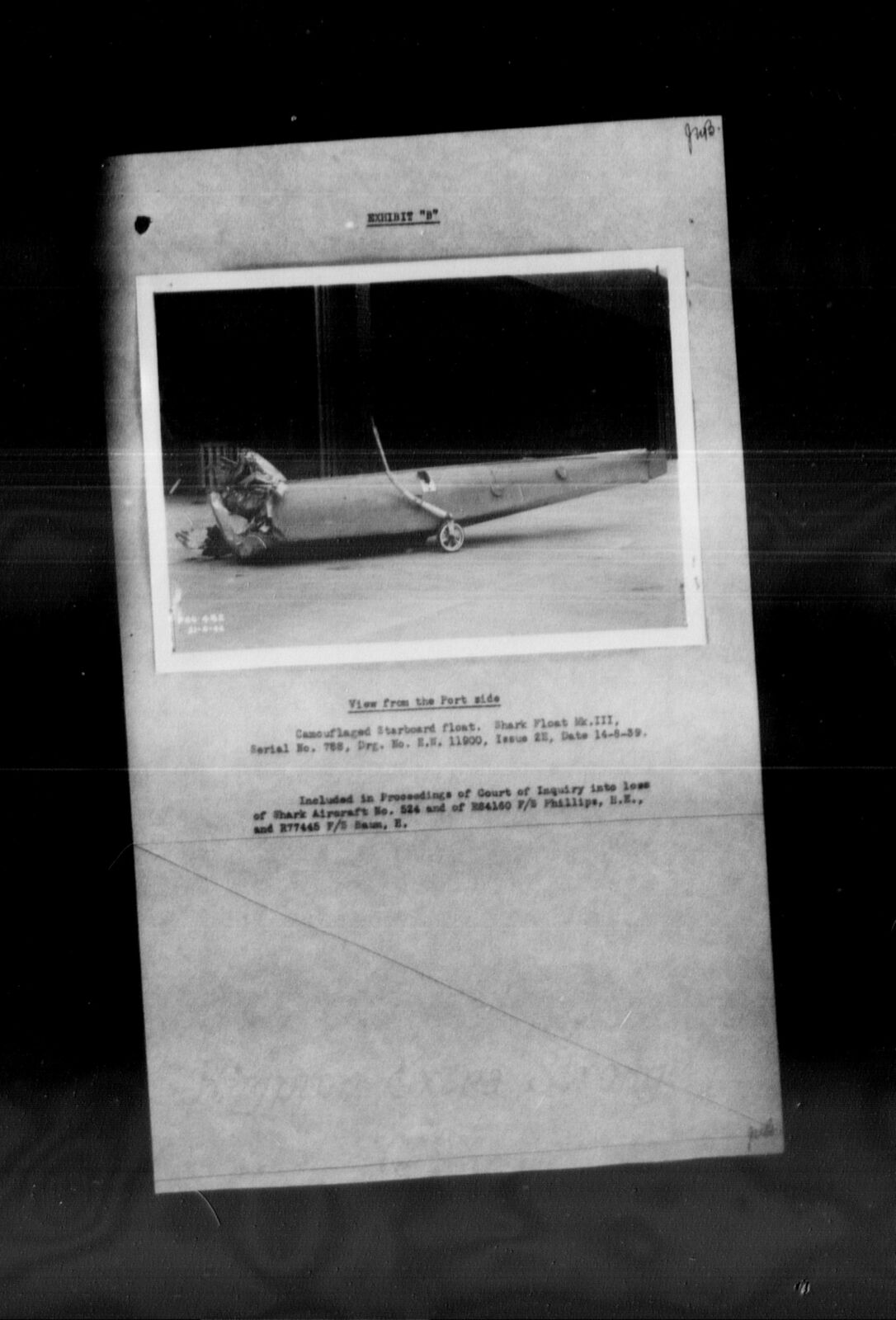

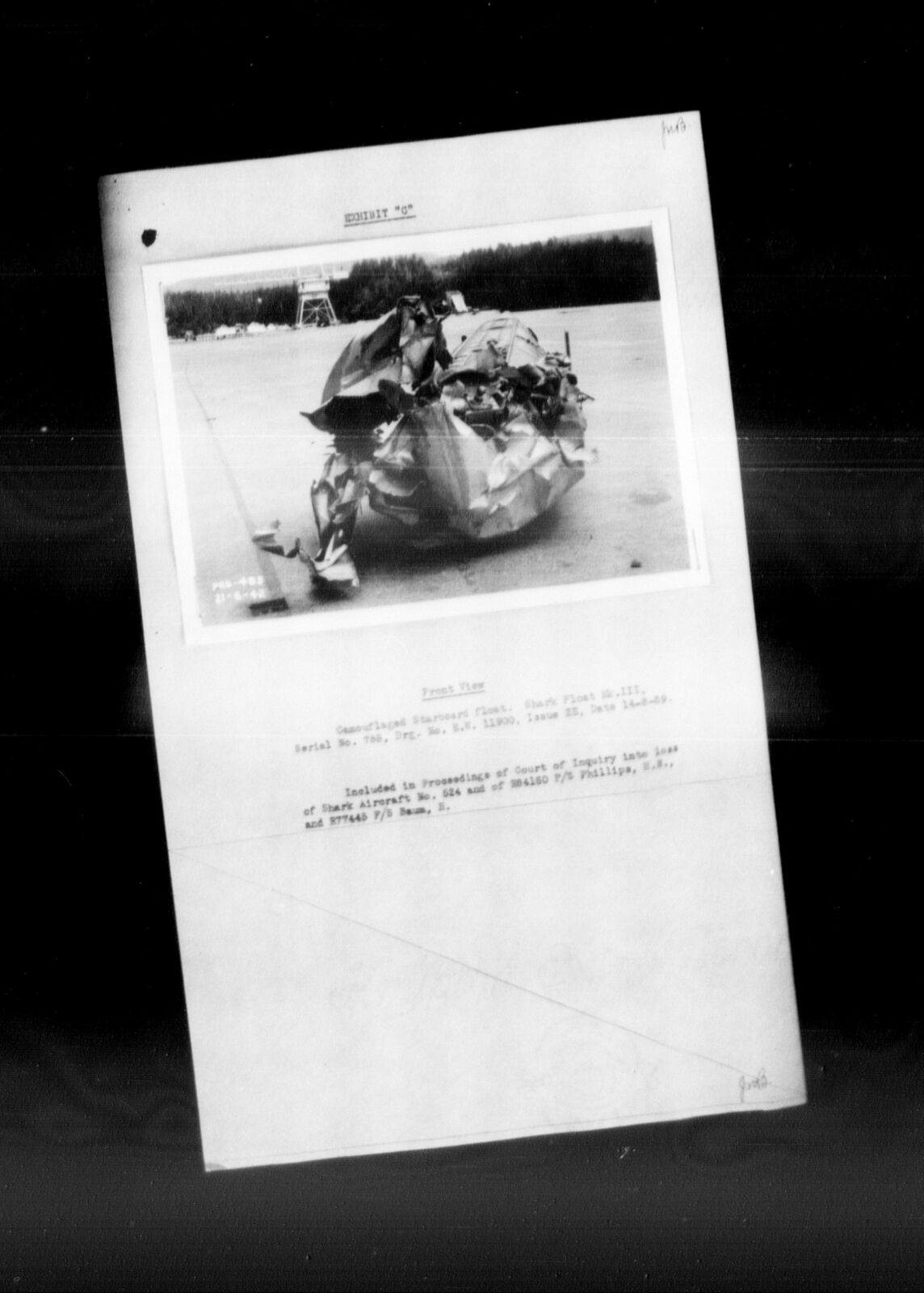

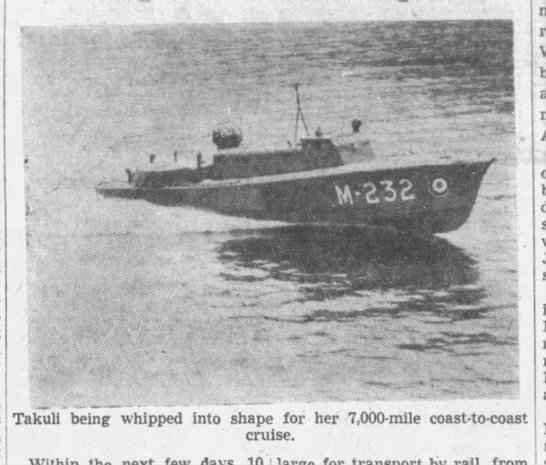

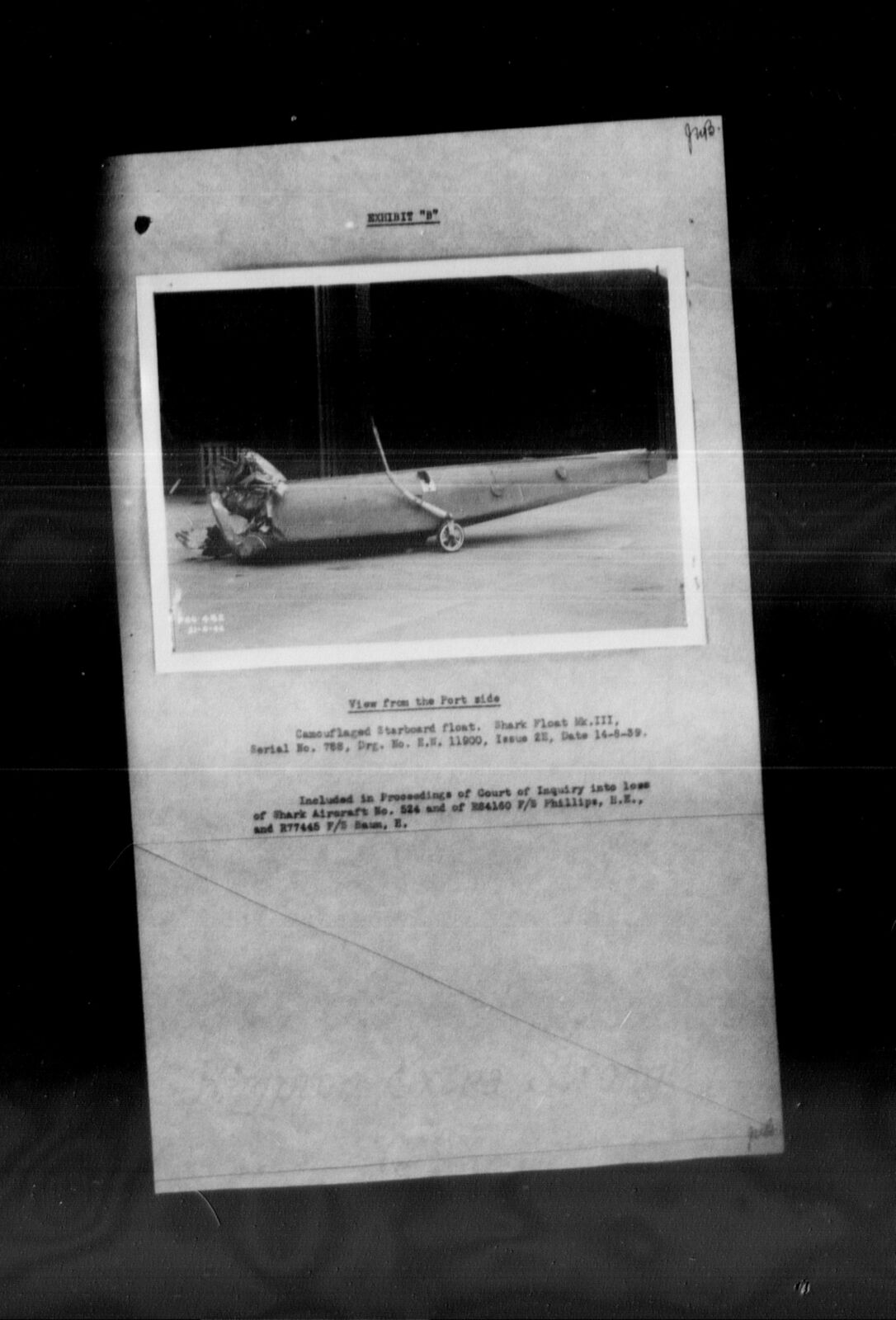

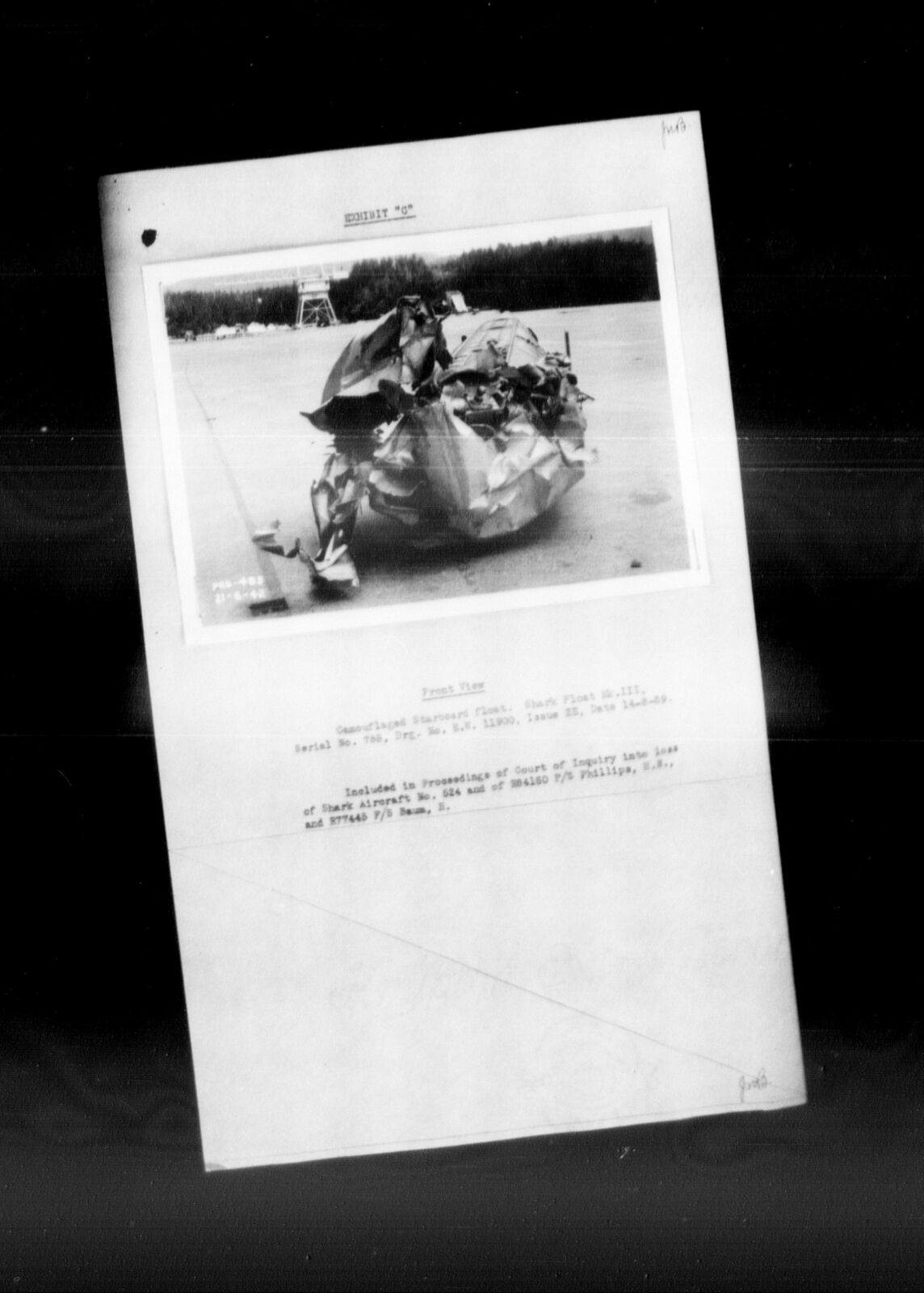

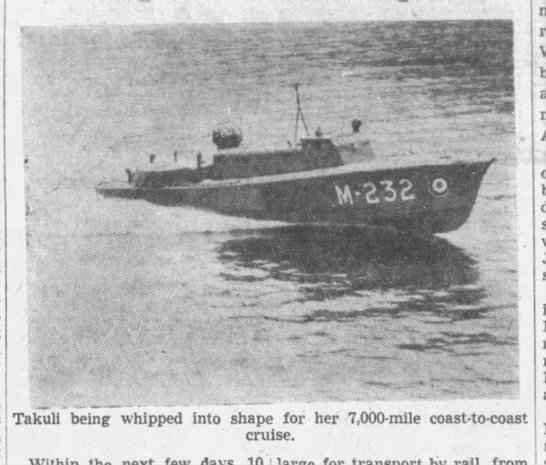

The second witness, F/O Edward Fleishman, C4164, Aeronautical Engineer, OC Maintenance Squadron, Prince Rupert, BC stated that he boarded the MV Takuli and proceeded to the scene of the crash. “The salvaged float had already been hoisted aboard the minesweeper ‘Courtney’ when we arrived. The locale of the crash was then searched in the hope of finding more salvage. No more was found. We then returned to the ‘Courtney’ and took the salvaged float on board the Takuli. The float was identified as a starboard float. A sweep of the district was again made but with no more wreckage found. It is difficult to explain the cause of the crash. The aircraft was apparently performing a normal maneuver. The appearance of the salvaged float indicates that the aircraft dove hard on into the water and the only explanation available is that the pilot lost control while executing the change in formation.”

The third witness, F/S Holbeck stated, “I signed the flight authorization sheet for local patrol exercises and the L .14 for Blackburn Shark 550. I then preceded to Blackburn Shark 550 which was in the inner Bay at Seal Cove, Prince Rupert British Columbia. On reaching the aircraft, I preceded to undo the bridle and prepare the aircraft for flight, then proceeded to the cockpit to do a cockpit check. All clear was given by the crewmen and the engine started. While taxiing and warming up the engine, I tested the magnetos and found them to be working satisfactorily. On receiving word from the wireless air gunner that all was clear, I took off. I proceeded to climb to an altitude of 1000 feet, to a position approximately due south of Lucy Island in order to make a full check of two minesweepers in the vicinity. I received the proper recognition signals from both minesweepers, then altered course to approximately due north in order to investigate a freighter which appeared to be approximately 30 miles away. While proceeding on this course, the wireless air gunner tapped me on the shoulder to notify me that another aircraft was approaching from the stern. The other aircraft was approaching in such a manner that my vision was partially blocked out due to the fact that it was approaching with the sun in its back. I made a 270 degree turn to the left and proceeded on a course approximately 90 degrees and did a weaving course in order to locate the other aircraft. The first indication of the other aircraft was that it was approaching on the port side at approximately 100 feet below and 100 yards to the rear. At this time, I approximated my altitude at between 500 and 600 feet and the time approximately 1030 hours. The pilot in the other aircraft gave every indication of wanting to fly formation. At that time, he appeared to want to change his position to the starboard side and on climbing in altering position, he was momentarily hidden from view. On next sighting, the aircraft it was in a climbing position, when suddenly it appeared to peel off and start a vertical descent. When the aircraft was at approximately 300 feet, it was lost sight of. I then made a turn to the left and on doing so sighted two floats, one vertical, the other parallel to the water, the fuselage having already disappeared below the surface. At this time the wireless operator attempted to contact the base and are not being able to do so a visual SOS was sent to the freighter and minesweeper in the vicinity. As soon as the freighter altered course, a landing was made at the wreckage. The wreckage was circled on the water for 10 to 15 minutes. Feeling that no more help could be given, I then proceeded to take off in order to return to base so as to notify the authorities. Whilst taking off, the wireless operator was instructed to signal the freighter to the effect that we were returning to base and to please stand by. On reaching base at 1106 hours, I immediately notified the Marine Section and the OC of No. 7 Bomber Reconnaissance Squadron of the accident. I then reported to No. BR Operations Room Officer for further instruction. It is my general belief that whilst pilot in Blackburn Shark 524 was climbing in altering position, due to the heavy landing of the aircraft and also due to the fact that it was climbing, the aircraft struck my slipstream and stalled. Immediately Shark 524 appeared to strike my slipstream, his port wing came up so as to put the wings in a vertical position and the aircraft proceeded to dive. I did not see the crash myself.”

Additional comments, “There were no definite plans made as to meeting in the air with Flight Lieutenant Phillips but it has been the general practice within the squadron that when two aircraft are on local patrol together an return to base, formation flying is practiced on route. Therefore, an approach of the other aircraft, due to his position, it appeared that he was attempting to formate on me at this time. After the aircraft was sighted, I immediately maintained a steady course so as to give the pilot a chance to come up on my side. Flight Lieutenant Phillips appeared to handle his aircraft very well in past formation.” When asked about other wreckage, Holbeck stated, “On landing there were two floats in the water and a few floating pieces of the propeller. One float submerged while we were circling the wreckage. When we landed, there were two floats one vertical and one horizontal. The floats were not attached the aircraft. All struts in bracings were severed from the floats. The aircraft was silver in colour and after the crash, I noticed one float was silver and the other camouflaged.”

The fourth witness, WAG F/S Harold Arthur Penn, flew with F/S Holbeck. “We didn't see the other aircraft for about 10 to 15 minutes. We came in contact with two minesweepers and sent the recognition signal. It was then that we noticed another aircraft coming towards us. We circled around for a few minutes until it caught up with us and then started formation flying. The airplane came up on the port side, when suddenly the pilot seemed to change his mind, and side slipped to come up on the other side of us, the starboard side. When the aircraft was halfway down the sideslip, its starboard wing seemed to slip over and then our fuselage blocked the view. F/S Holbeck want to find out whether the pilot was Flight Sergeant Phillips and banked a bit. It was then that I noticed the aircraft had struck the water, so we circled around once. In the meantime I tried to get in contact with the base, then after one circle, Flight Sergeant Holbeck landed and we taxied around for about 15 minutes but could find no sign of life at all. The only remains of the aircraft were the two floats and while we were there in the water, one float went down… coming into the base F/S Holbeck started on a slow glide down and landed by the cold storage plant at Seal Cove, Prince Rupert. He then notified the hospital boat to come as soon as we tide up to the buoy then he telephoned while I went to the hospital boat to direct them to the scene of the crash. When we got out to the scene of the crash, the minesweeper ‘Courtney’ was standing by with the last remaining float on deck. We transferred the float from the ‘Courtney’ to the MV Takuli, hospital boat, and preceded to patrol for signs of oil in the water. The patrol took practically all afternoon. We could find no sign of the aircraft as we headed back to base at approximately 1500 hours.” He continued, “I could see part of the fuselage and the tail going down. I could not see the occupants. I could not see whether the coupe top was open.”

The fifth witness, Lt. Magnussen, Officer of the ‘Courtney ‘stated that he saw a slight trace of oil on the surface, but no oil bubbling up from the aircraft.

The sixth witness, Ordinary Seaman Robert Herbert Bowick of the ‘Courtney’ stated that he saw one of the aircraft flying lower than the other by at least 100 feet and that the one aircraft struck the water at about a 90 degree angle, plus did a wing over.

The seventh witness, Leading Signalman Donald Douglas McKay stated that he also saw that one plane was flying lower than the other and appeared to be rejoining the other aircraft. He concurred with Bowick on the angle which the plane struck the water.

The ninth witness, F/O William Francis Gillespie, Master of the Motor Vessel Takuli M232, felt that it was quite possible to locate the wreckage, but salvaging it was slim because it was in at least 60 fathoms of water. [110 metres]

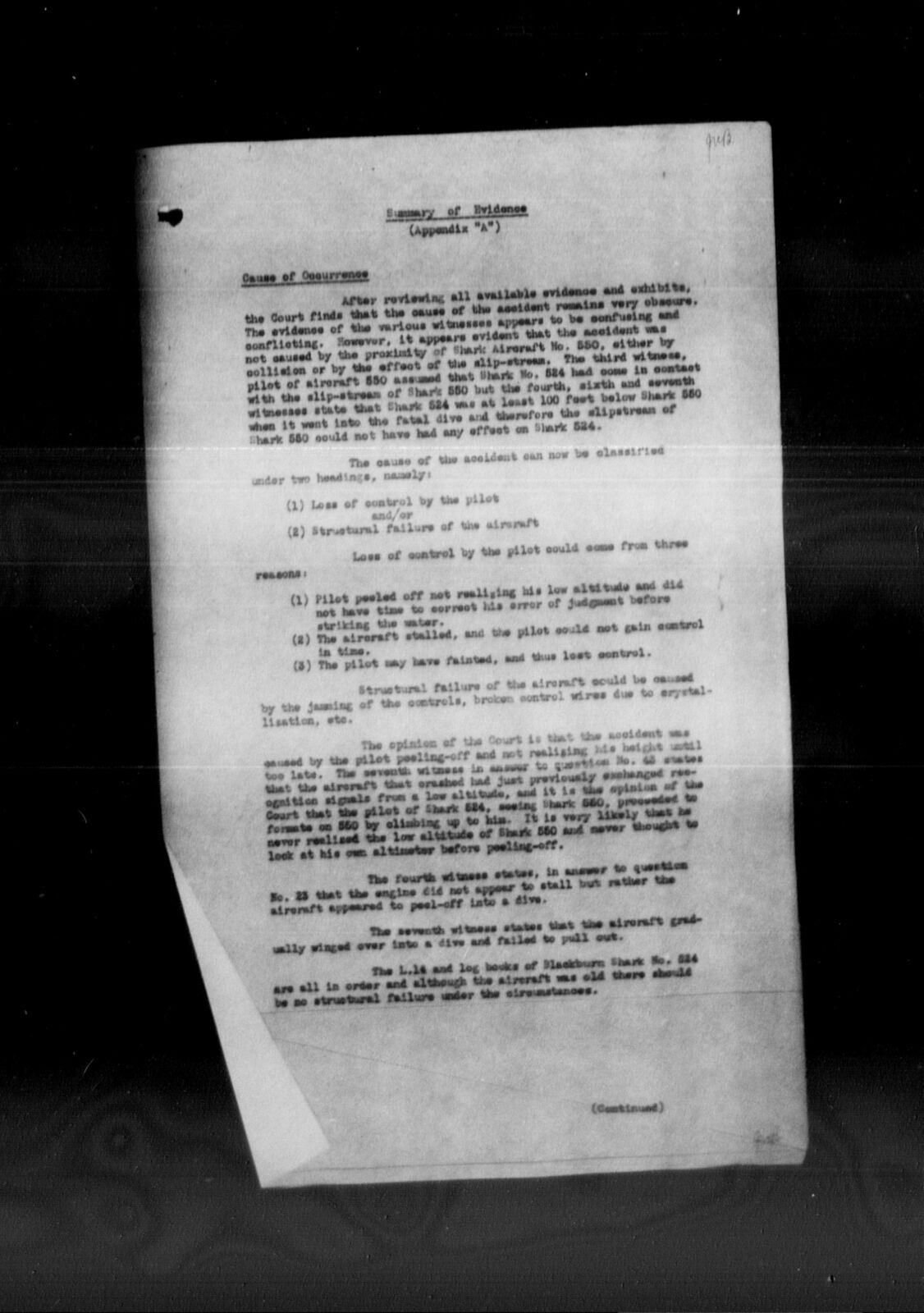

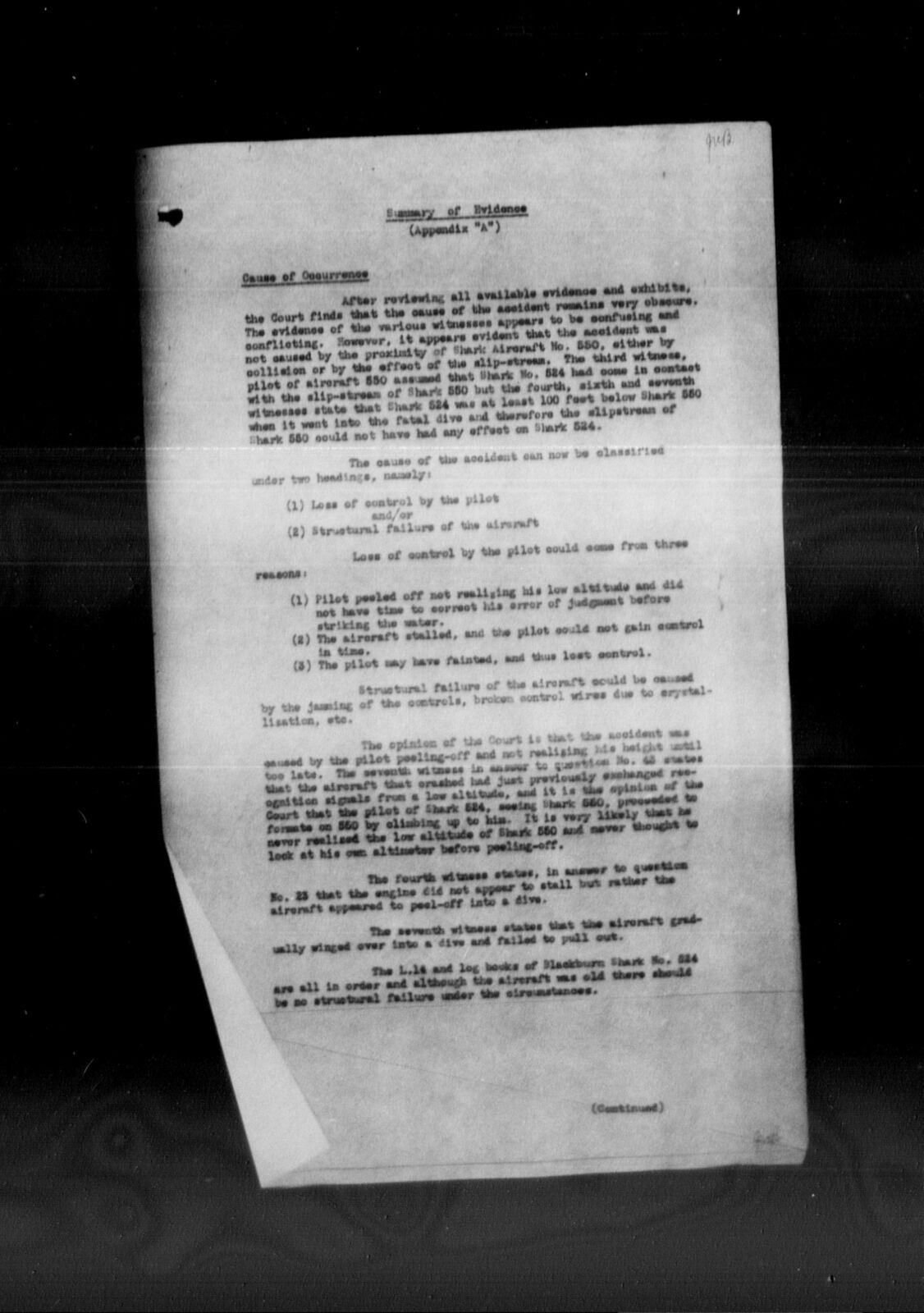

Cause of Occurrence: Conflict of information. Accident remained obscure. Possibility that the pilot lost control of the plane [pilot peeled off not realizing his low altitude and did not have time to correct his error of judgment before striking the water; the aircraft stalled and the pilot could not gain control in time; pilot may have fainted and thus lost control]; or there was a structural failure of the aircraft [jamming of controls, broken control wires due to crystallization]. The Court felt that the pilot made an error in judgment on his height.

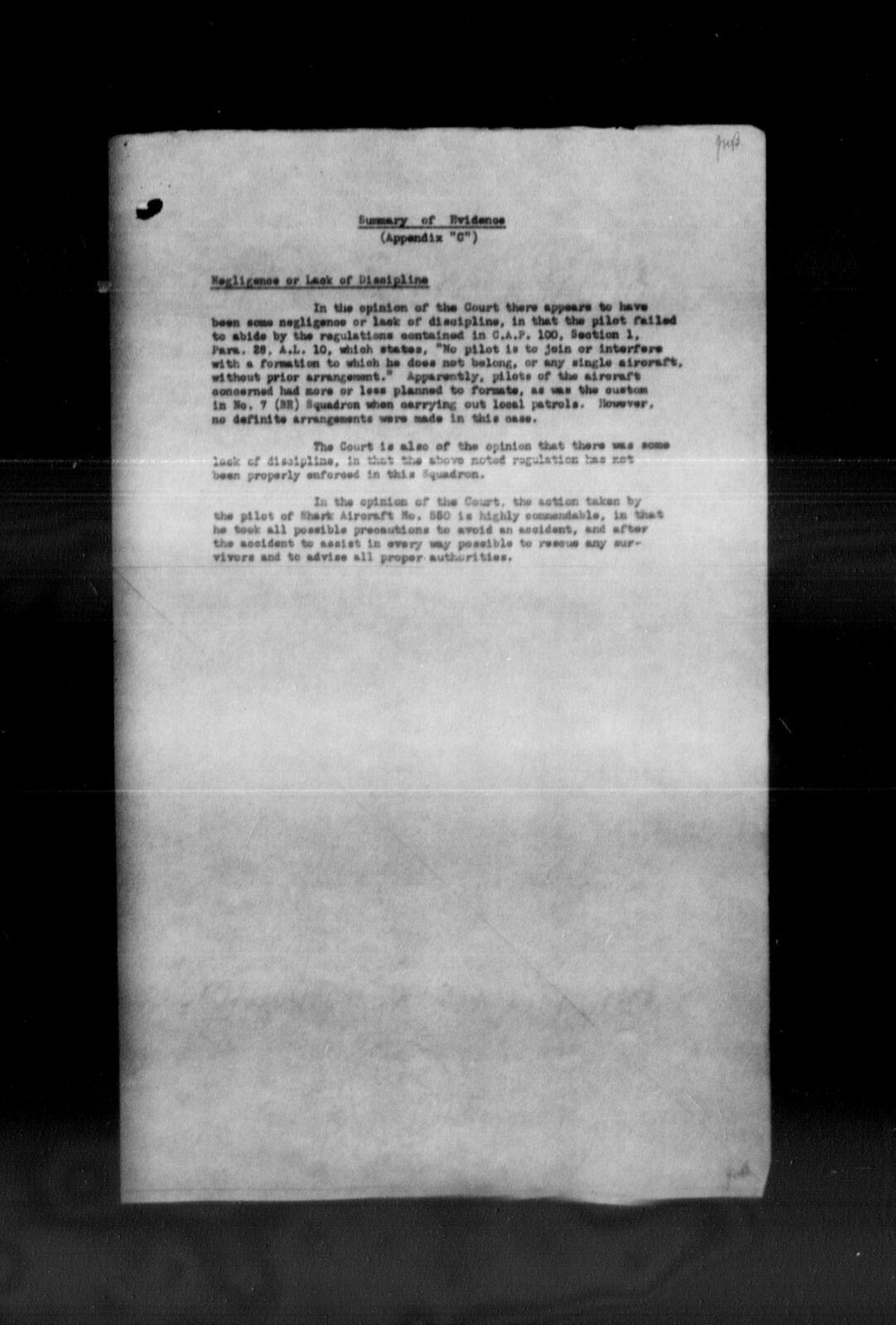

Negligence/Lack of Discipline was deemed cause of the crash. [See documents above.]

“Error of judgment on part of the pilot, in that he did not realize his low altitude and was unable to recover. Formation flying in the Blackburn Shark be carried out at 2000 feet or over and at no height less than that. It should be stressed that the pilots of this Station keep a closer check on their flying instruments whilst in the air.”

AC2 Seymour Baum requested his brother’s logbook. His mother was the beneficiary to his estate.