September 6, 1920 - July 16, 1942

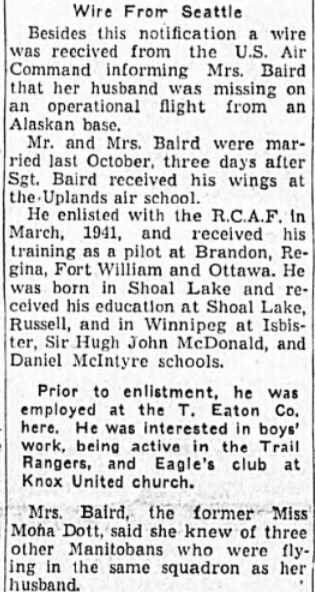

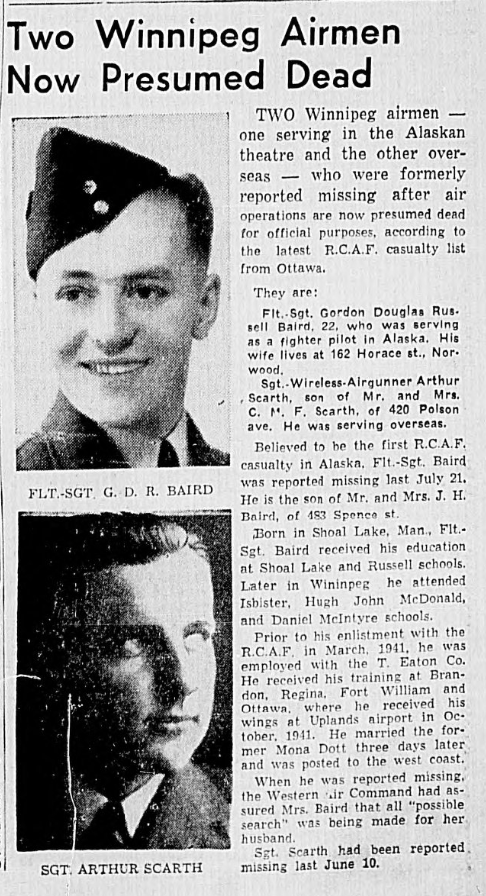

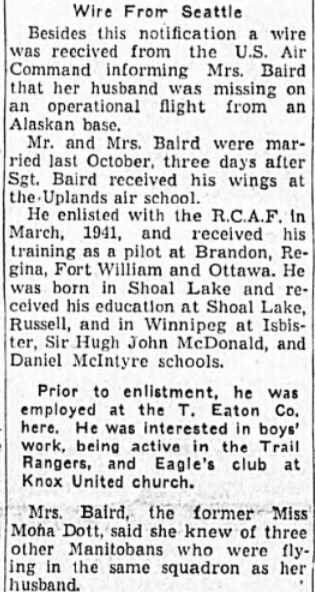

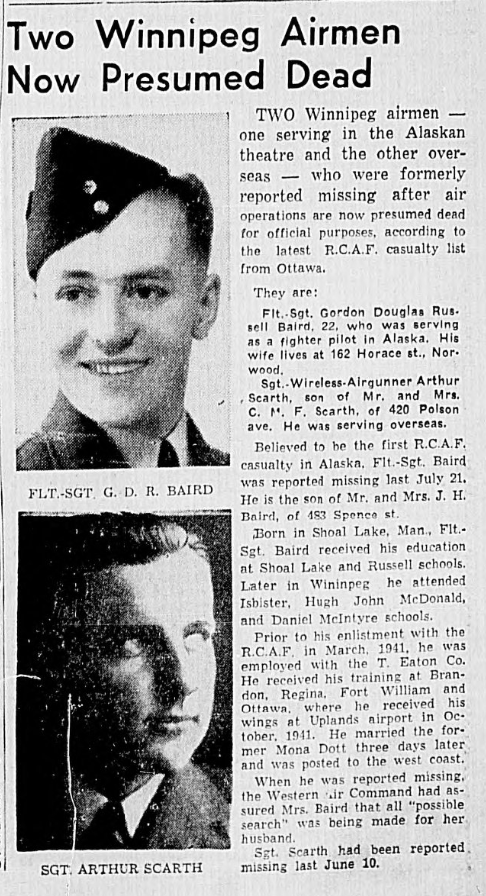

Born in Shoal Lake, Manitoba, Gordon Douglas Russell Baird was the son of James Humphrey Baird, carpenter, and Sarah Amelia (née Russell) Baird of Winnipeg, Manitoba, brother of Warrant Officer Nelson George Baird, RCAF, (1923- 1945), Charles Freeman Baird (1910-1988) and Cecil John Smith Baird (1916-2009). Cecil was with the Canadian Army, a paratrooper. The family attended the United Church.

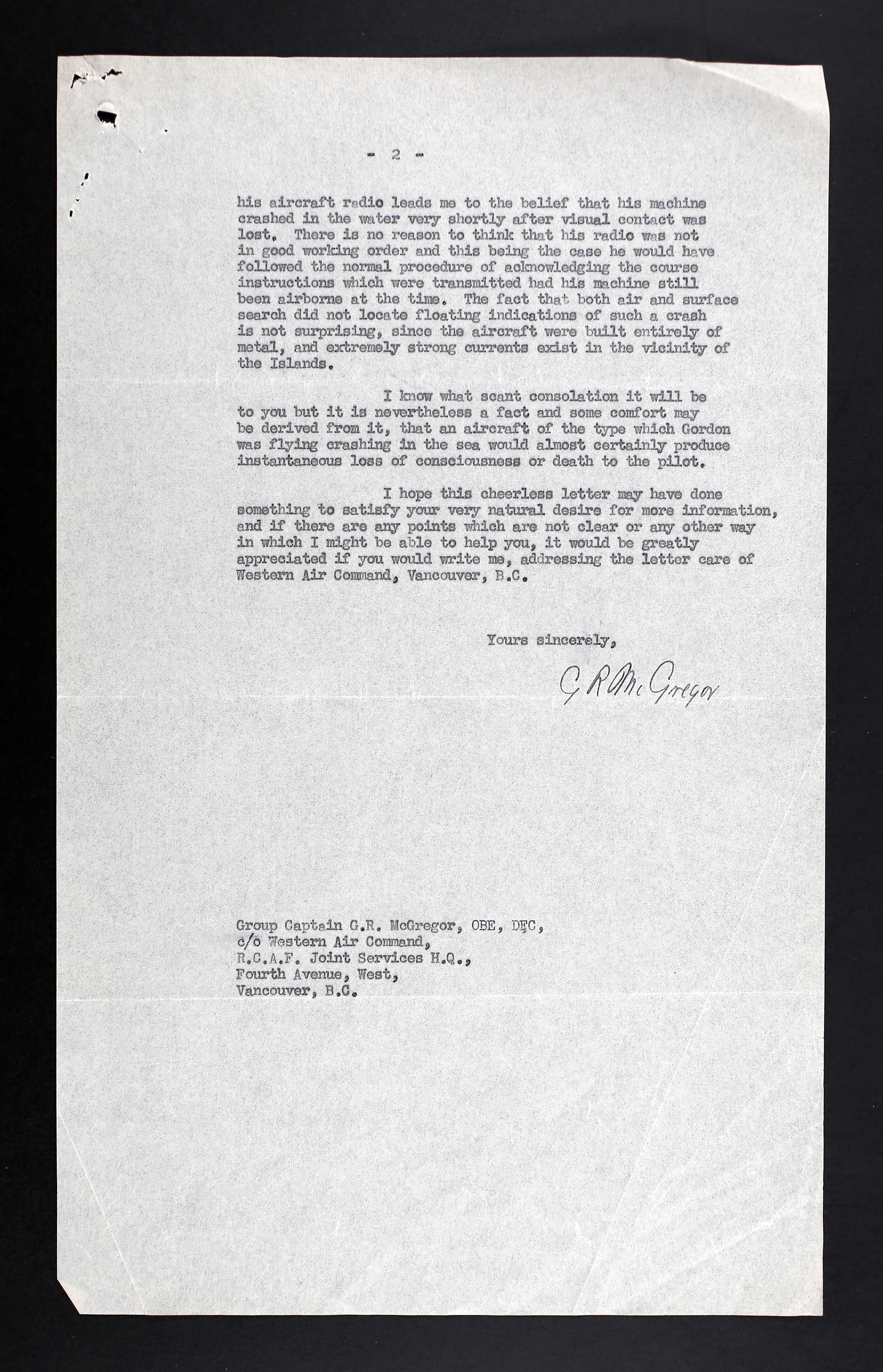

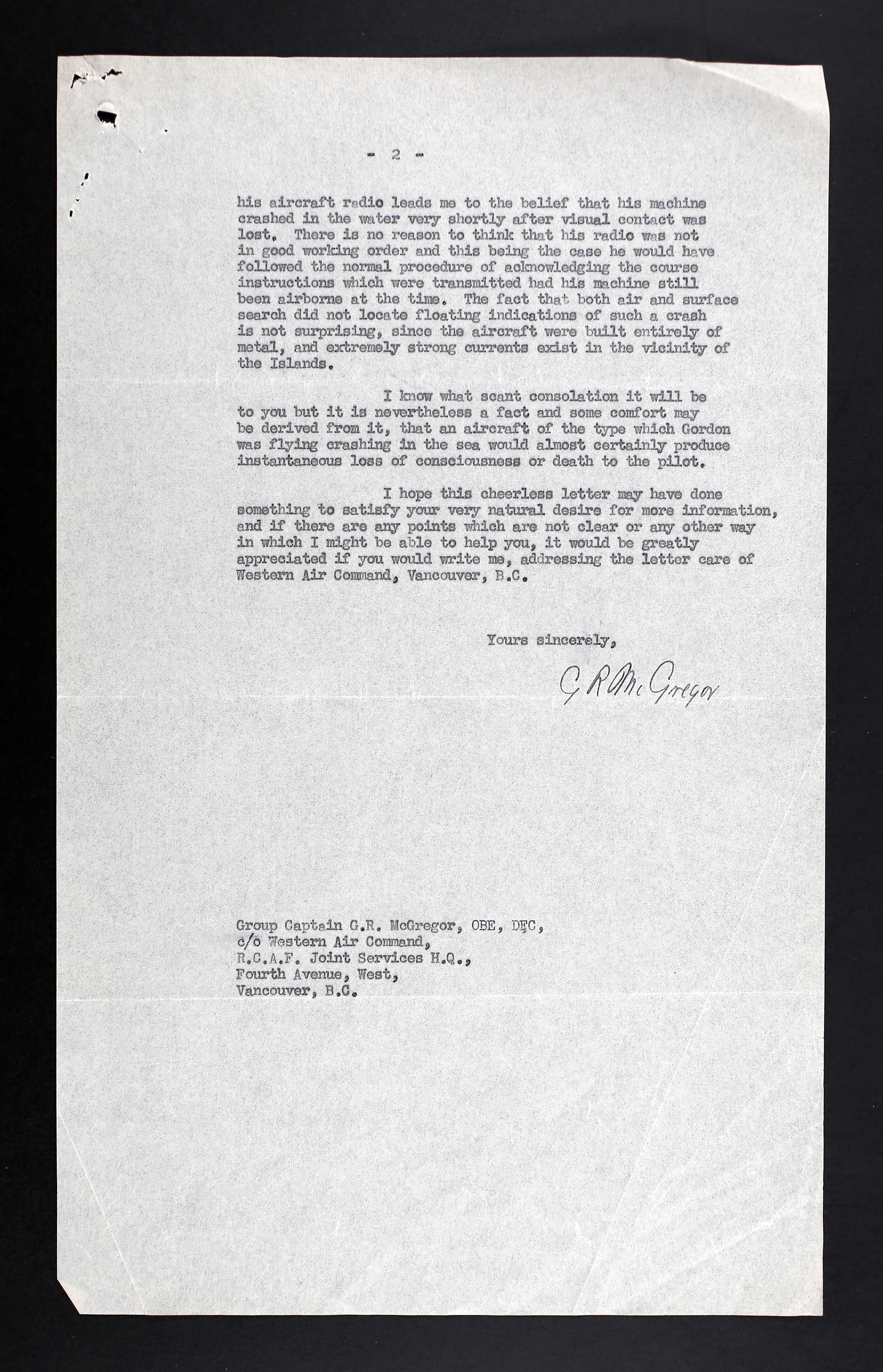

Gordon, known as Gordie, had junior matriculation and was working at T. Eaton Co. as a mail order clerk and then as a mail order complaint correspondent in Winnipeg at the time he enlisted with the RCAF in September 1940. He had been with the 2nd Armoured Car Regiment, as a trooper, July 1940 until March 1941, when he was accepted into the RCAF.

Gordon enjoyed bicycle riding, as well as a variety of sports. In 1932, he had fractured his clavicle and had an appendectomy in 1940. He stood 5’9 ½” tall, weighing 150 pounds. He had brown eyes and hair, with a fair complexion.

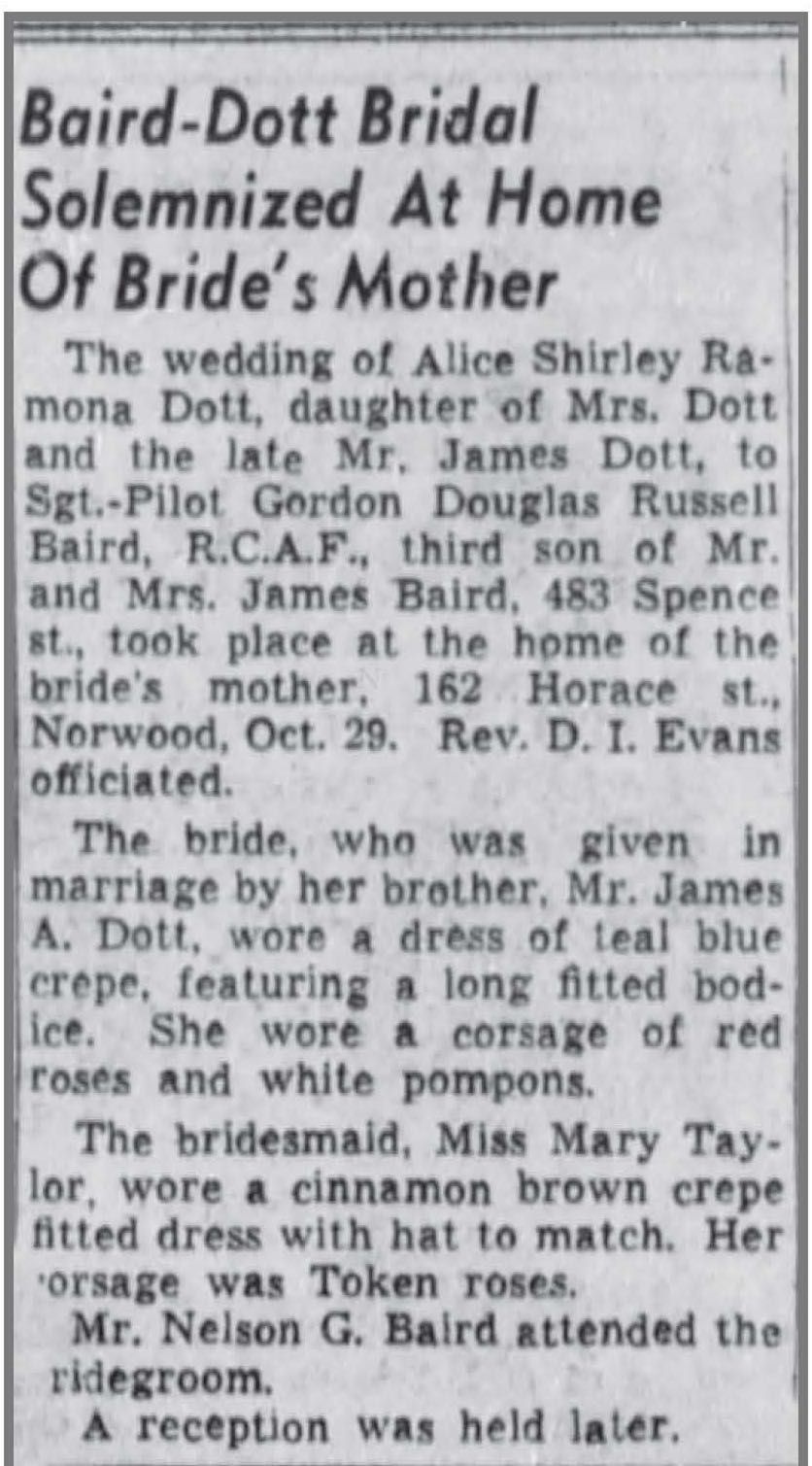

He was the husband Alice Shirley Ramona ‘Mona’ (nee Dott) Baird, Norwood, Manitoba, a suburb of Winnipeg. They were married on October 29, 1941.

Gordon started his journey through the BCATP at No. Manning Depot, Brandon, Manitoba March 4 until April 9, 1941. He was then sent to Winnipeg to No. 8 Repair Depot until May 16, when he arrived at No. 2 ITS, Regina. “Appears to be rugged, cool, alert, and industrious type. His sports are average.”

From there, he was sent to No. 2 EFTS, Fort William, Ontario June 21 until August 7, 1941. Ground School: “Progress satisfactory. 31st out of 32 in class. 62%. Average ability; has ability but shows only very little application.” Other evaluations: “This lad is a consistent flyer. He hasn’t as far as I know, displayed any dangerous tendencies. He is an intelligent and eager pupil.”

He found himself at No. 2 SFTS Uplands, Ontario until October 25, 1941, where he received his Pilot’s Flying Badge. “High average pilot. Enthusiastic and confident. Instrument flying average. Recovery from unusual positions weak.” In Ground School: “A poor student who tries hard but is slow to learn. Wants to be a fighter pilot. Good appearance.” Other comments: “Average type, persevering, respectful and cooperative.”

Gordon remained in the Ottawa area at RCAF Station, Rockcliffe until December 15, 1941 when he was sent to 111 (F) Squadron, Patricia Bay, British Columbia. “A good pilot, a quiet steady reliable type. Worthy of promotion.” Six months later, he was in Alaska. (While at Patricia Bay, he was involved in an accident in Kittyhawk 911 on January 24, 1942. “I was off the runway while landing.” He had ground looped, damaging the propeller, starboard wing, flap and wheel.)

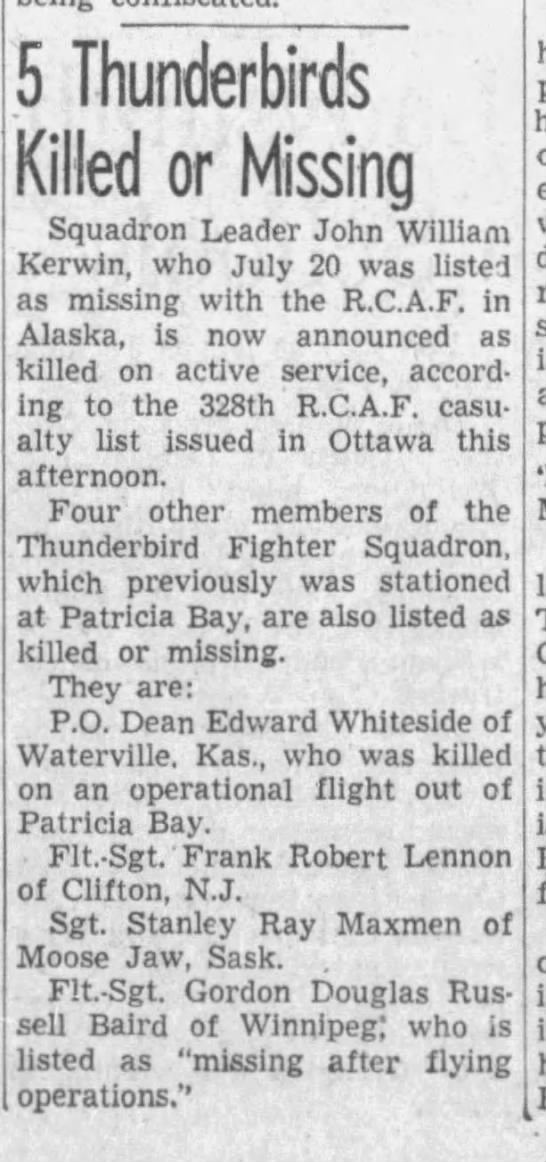

On July 16, 1942, Kittyhawk I AL 166 LZ-O flown by F/S Baird was on patrol, based at Elmendorf Field, Anchorage, Alaska. He became lost in a relocation mission and died at sea, along with four other pilots and seven planes. They were making their way to Umnak Island in the Aleutian chain.

From 111(F) Squadron’s website (https://www.rcaf111fsquadron.com/sacrifices.html):

Here is the drama of those few days as recorded in the Squadron Daily Diary:

"July 13, 1942: Local flying and some formation carried out, and some instrument flying. W/C McGregor and six pilots left Elmendorf enroute to Umnak and Cold Bay, On the way to Umnak Flt/Sgt Schwalm was forced to bail out due to failure of the entire electrical system. On arrival at Naknak P/O Lynch crashed on landing. W/C McGregor and S/L Kerwin took off from Naknak to search. They were unsuccessful, but a DC3 Transport piloted by Captain Fillmore, U.S.A. Air Corps sighted Schwalm and on landing at Naknak returned with emergency rations, maps, and first aid kit. Two D.C. 3 Transports left at the same time as our flying pilots, transporting seven pilots and twenty-six men. An advance party consisted of F/O Cowan, the Medical Officer, F/O Paynter and eleven men left at 08:30 hours for Cold Bay, enroute to Umnak, arriving Cold Bay at 13:00 hours.

July 14, 1942: The advance party departed Cold Bay for Umnak at 13:00 hours, but were unable to get through due to weather conditions. W/C McGregor returned to Elmendorf to collect two more pilots and aircraft and to find out what was being done regarding F/Sgt Schwalm. In the meantime, the "Alaska Star Airlines" had picked Schwalm up at Lake Iliana. W/C McGregor returned to Umnak with P/O Eskil and F/Sgt Baird arriving at 17:40 hours.

July 15, 1942: Weather bad today. Pilots unable to leave Naknak. Good sample of camp life eating everything off one plate and using a wooden spoon.

July 16, 1942: W/C McGregor and six pilots left Naknak today for Cold Bay at 10:00 hours, accompanied by the two Transports, arriving at Cold Bay at 12:00 hours. At 13:30 hours one of the Transports piloted by Captain Fillmore left Cold Bay for Umnak. Weather was reported as suitable for the flight. At 14:00 hours, seven of our Kittyhawks took off for Umnak. Shortly after passing Dutch Harbor, the aircraft ran into bad weather. Fog was in front, behind and on the starboard side. The Wing Commander gave the order to turn back but owing to the low ceiling (50 feet), the others lost him in the turn and went into the fog. W/C McGregor landed at Cold Bay and one aircraft piloted by P/O Eskil arrived at Umnak. Apparently the remaining five had been lost. Two Transports and nine pilots, one Medical Officer, and seventeen men arrived at Umnak. Radio communications between Transports and P40's was very poor. The Wing Commander made an attempt to locate the missing aircraft and pilots in a P.B.Y., but to no avail, owing to hopeless weather conditions...

July 17, 1942: Two of our P40's were located in the morning on a hillside on Unalaska Island. A search party left by boat from Umnak, located the aircraft , and identified P/O Dean Edward "Whitey" Whiteside and F/Sgt Frank "Pop" Lennon. The bodies were brought back to Umnak. W/C McGregor arrived at Umnak."

Two others, Sergeant Pilot Stan Maxmen and Squadron Leader John William Kerwin, had also slammed into the mountain in the fog. Flight Sergeant Gordon Douglas Russell "Gordie" Baird became disoriented and probably flew until he ran out of fuel, crashing into the sea. He was never seen again.

Five pilots and seven aircraft lost in a relocation mission.

The Daily Diary version of the tragedy is terse and maddeningly without detail. What we do get is that the weather conditions were terrible and that communication was difficult, both within the formation and with ground and other support aircraft in the area. It is hard to imagine just how isolated a pilot is under such conditions and how vulnerable.

We have two witness accounts of the doomed flight. One from Squadron Leader McGregor who led the formation and the other from then-Pilot Officer Eskil, the only one who reached the intended destination that day. The two accounts were in substantial agreement as to what happened. P/O Eskil's account is richer in the details that can help us get a feel for the mission. Here is an excerpt from his very thorough and full report:

"After rounding Makushin Cape (Unalaska Island) and altering course to roughly follow the shoreline - weather became progressively worse. Fog banks and showers continually appeared to the north. We flew through several areas about 50 feet above the water. I could hear F/L Kerwin talking to Captain Fillmore (in an American C-53 support aircraft) intermittently but they seemed to be making very poor radio contact. I could not tune either one clearly.... The air seemed clear near the water but visibility was very poor - much impeded by large areas of dense fog and showers. We were forced very near the water.

... we were forced right along the shore by a dense fogbank about 200 yards offshore. We were forced to about 20 feet from the water and I estimate the ceiling at about 50 feet. We were flying with the Wing Commander leading a "VIC" consisting of F/L Kerwin's section (with Maxmen) and Pilot Officer Whiteside's section (with Lennon) on the starboard of the Wing Commander, and my section (with Baird) off the port. Sections were about three to four spans apart and ships in the sections slightly closer. F/Sgt Baird had overtaken me and slid over abruptly, forcing me to pass through his slipstream. We were very low and I dropped back slightly while righting my ship. As I was moving up to form on F/Sgt Baird's port wing, the Wing Commander ordered a turn to port. I was trailing the Wing Commander and Baird by 100 yards when the turn began. I was too low to drop into proper position for a turn and thus lost sight of all the other ships when I began my turn. I turned as tight and as low as I dared but sighted an aircraft well ahead of me cutting me off. Afraid that I would fly into the green beneath me continuing my turn and increasing throttle to about 37 Hg. My gyro horizon was out so I had trouble in maintaining steep climb and turn. At about 500 feet freezing mist appeared on my windscreen so I undid my harness and removed my oxygen and radio connections - intending to bail out if I stopped gaining height because of icing. At 4800 ft I broke through between cloud layers, continued to turn and plugged in my radio... (After being momentarily disoriented by cloud and fog and making a couple of course adjustments) In a few minutes I ended up in what turned out to be the only hole in the area and sighted the Umnak air base... I phoned Captain Fillmore to clear me so I would not be fired on and proceeded to land..."

By the time P/O Eskil was plugging in his radio, four of his fellow pilots were dead. And one was probably flying in circles. Sgt Baird wouldn't have known his fate until his fuel ran out. He must not have heard McGregor, or Fillmore or Eskil calling for him. He might have heard McGregor's order to the formation to turn left. He was turning left when he crossed in front of Eskil. If so, that was his last connection with his squadron.

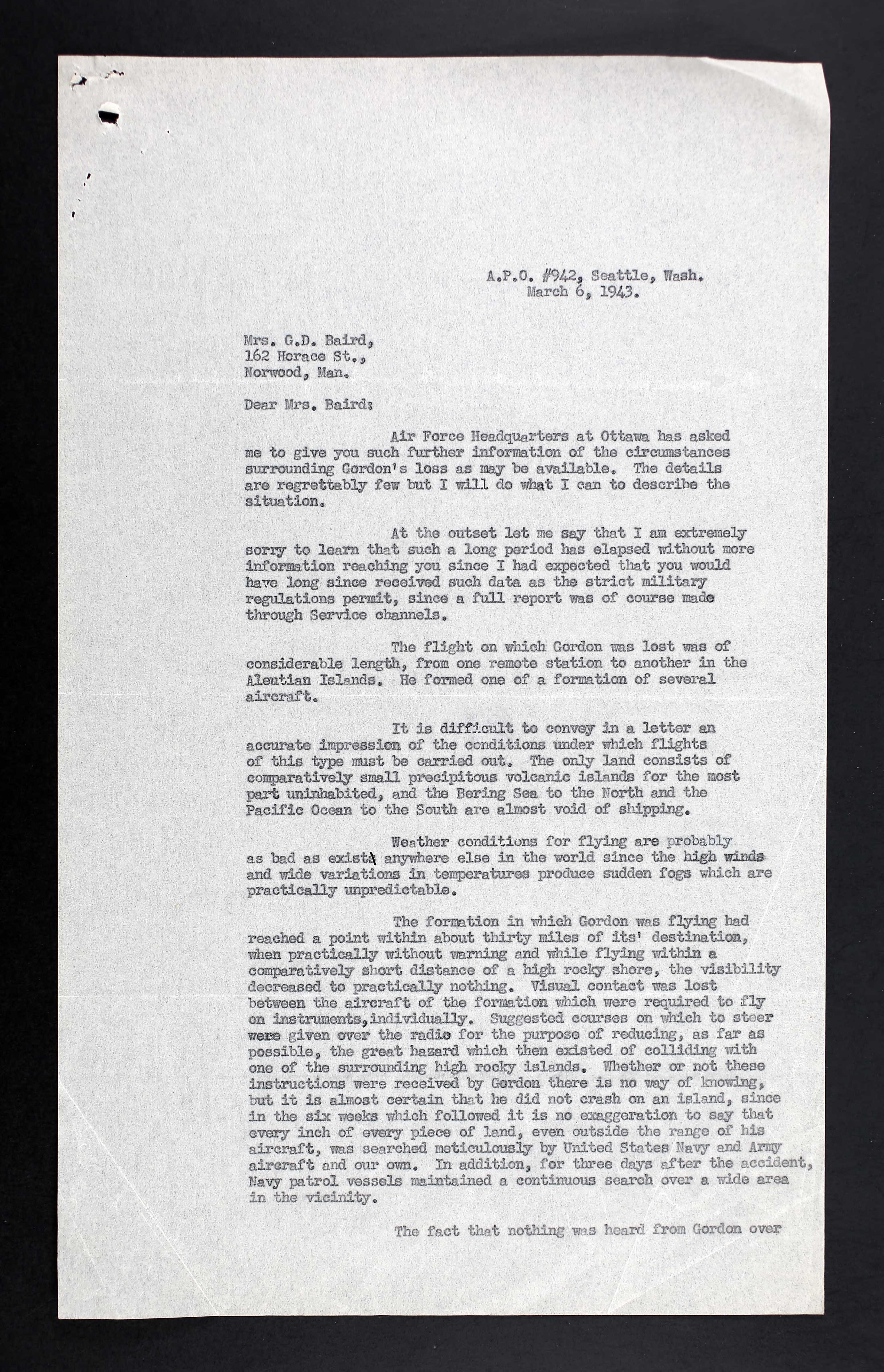

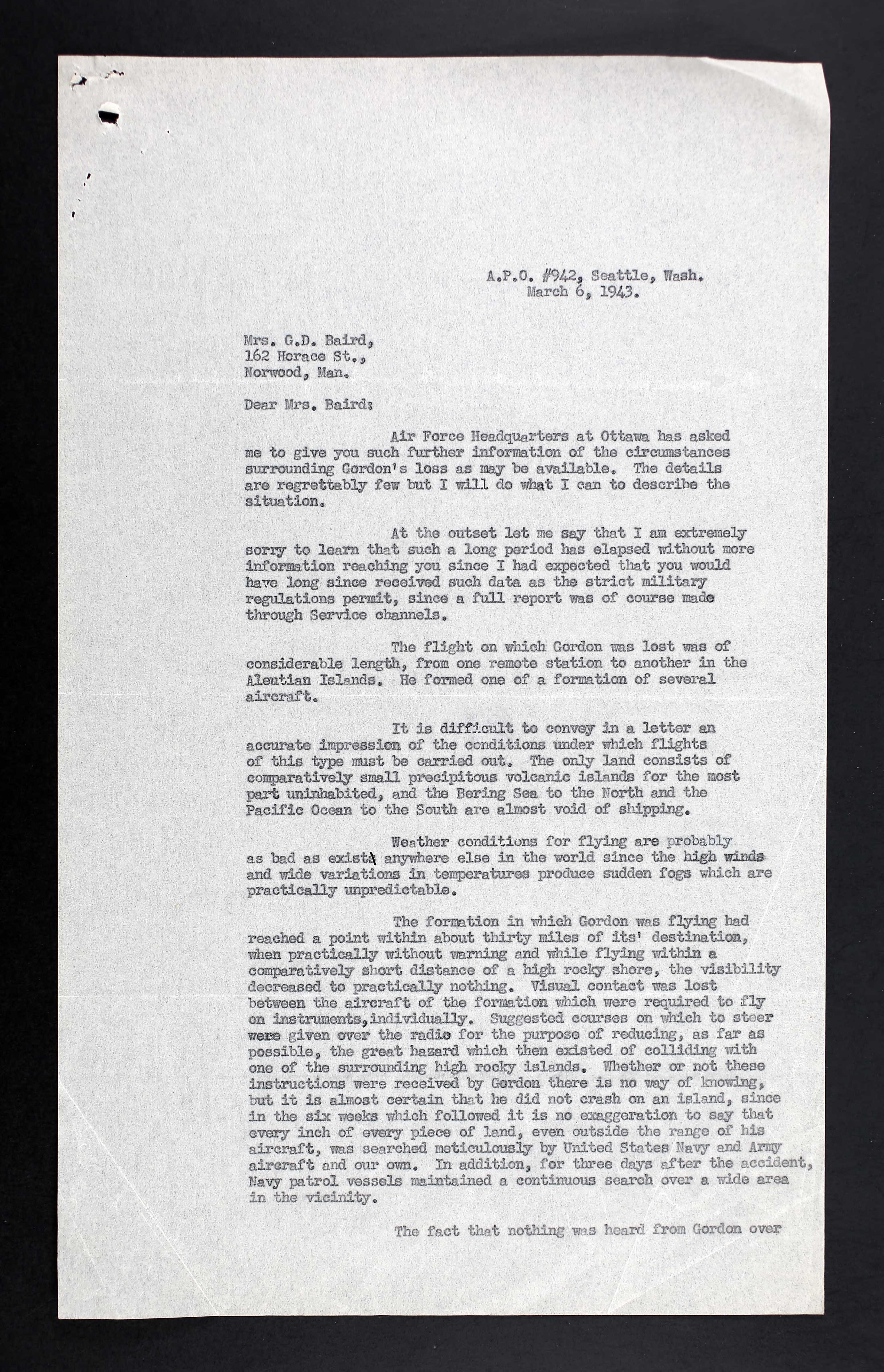

Alice wrote a letter to Commanding Officer G. R. McGregor, RCAF Wing, Alaska September 13, 1942. “…It was very good of you to explain about the search being carried out by both United States and Canadian Services for my husband Gordon. I fully appreciate this and understand why you consider there is very little hope for his safe return. Because of RCAF regulations, no details will be available at present, but if at a later day it is possible to send them, I certainly would appreciate hearing from you.”

In January 1943, she wrote another letter indicating she had no further information about what happened to Gordon. “I have waited six long months to hear some of the details of what or how it happened to my husband...”

In March 1943, she received a letter from C/O McGregor. “The flight on which Gordon was lost was of considerable length, from one remote station to another in the Aleutian islands. He formed one of a formation of several aircraft. It is difficult to convey in a letter an accurate impression of the conditions under which flights of this type must be carried out. The only land consists of comparatively small precipitous volcanic islands for the most part uninhabited, and the Bering Sea to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the South are almost void of shipping. Weather conditions for flying are probably as bad as exists anywhere else in the world since the high winds and wide variations in temperatures produce sudden fogs which are practically unpredictable.

The formation in which Gordon was flying had reached a point within about 30 miles of its destination, which practically without warning and while flying within a comparatively short distance of a high rocky shore, the visibility decreased to practically nothing. Visual contact was lost between the aircraft of the formation which were required to fly on instruments individually. Suggested courses on which to steer were given over the radio for the purpose of reducing, as far as possible, the great hazard which then existed of colliding with one of the surrounding high rocky islands. Whether or not these instructions were received by Gordon there is no way of knowing, but it is almost certain that he did not crash on an island, said this since in the six weeks which followed, it is no exaggeration to say that every inch of every piece of land, even outside the range of his aircraft, with searched meticulously by the United States Navy and army aircraft and our own. In addition, for three days after the accident, Navy patrol vessels maintained a continuous search over a wide area in the vicinity. the fact that nothing was heard from Gordon over his aircraft radio leads me to believe that his machine crashed in the water very shortly after visual contact was lost. There is no reason to think that his radio was not in good working order and this being the case he would have followed the normal procedure of acknowledging the course instructions which were transmitted had his machine still been airborne at the time period the fact that both air and surface search did not locate floating indications of such a crash is not surprising, since the aircraft were built entirely of metal, and extremely strong currents exist in the vicinity of the islands. I know what scant consolation it will be to you but it is nevertheless a fact and some comfort may be derived from it, that an aircraft of the type which Gordon was flying crashing into the sea would almost certainly produce instantaneous loss of consciousness or death to the pilot. I hope this cheerless letter may have done something to satisfy your very natural desire for more information, and if there are any other points which are not clear or any other in which I might be able to help you, it would be greatly appreciated if you would write to me addressing the letter care of Western Air Command, Vancouver BC.”

By January 1947, Alice remarried and was Mrs. Eric Wheeler, living in Hamilton, Bermuda, then North Shore, Pembroke, England. (In January 1945, she had written to the Department of Statistics in Ottawa enquiring to her marital status since she had been a widow of 2 ½ years. “My husband was lost in July 1942, first being reported missing, then six months later, presumed dead. Am I considered single and able to enter marriage legally again or do I have to wait a certain length of time?”)

From the Canadian Virtual War Memorial site: “Flight Sergeant Gordon Baird was honoured on February 28, 1995 by the Province of Manitoba when it named Baird Bay on Baird Island for him. Baird Island is named for his brother Nelson Baird.”