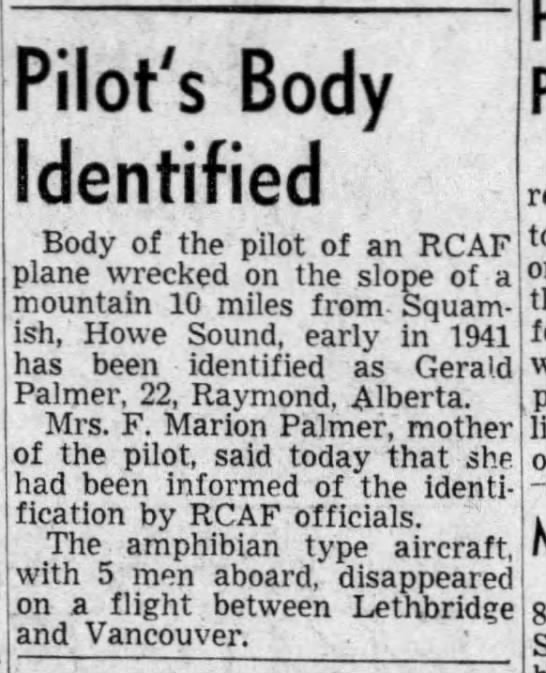

May 5, 1919 - November 4, 1941

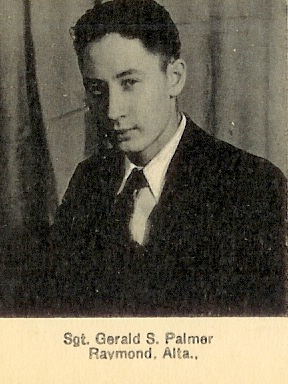

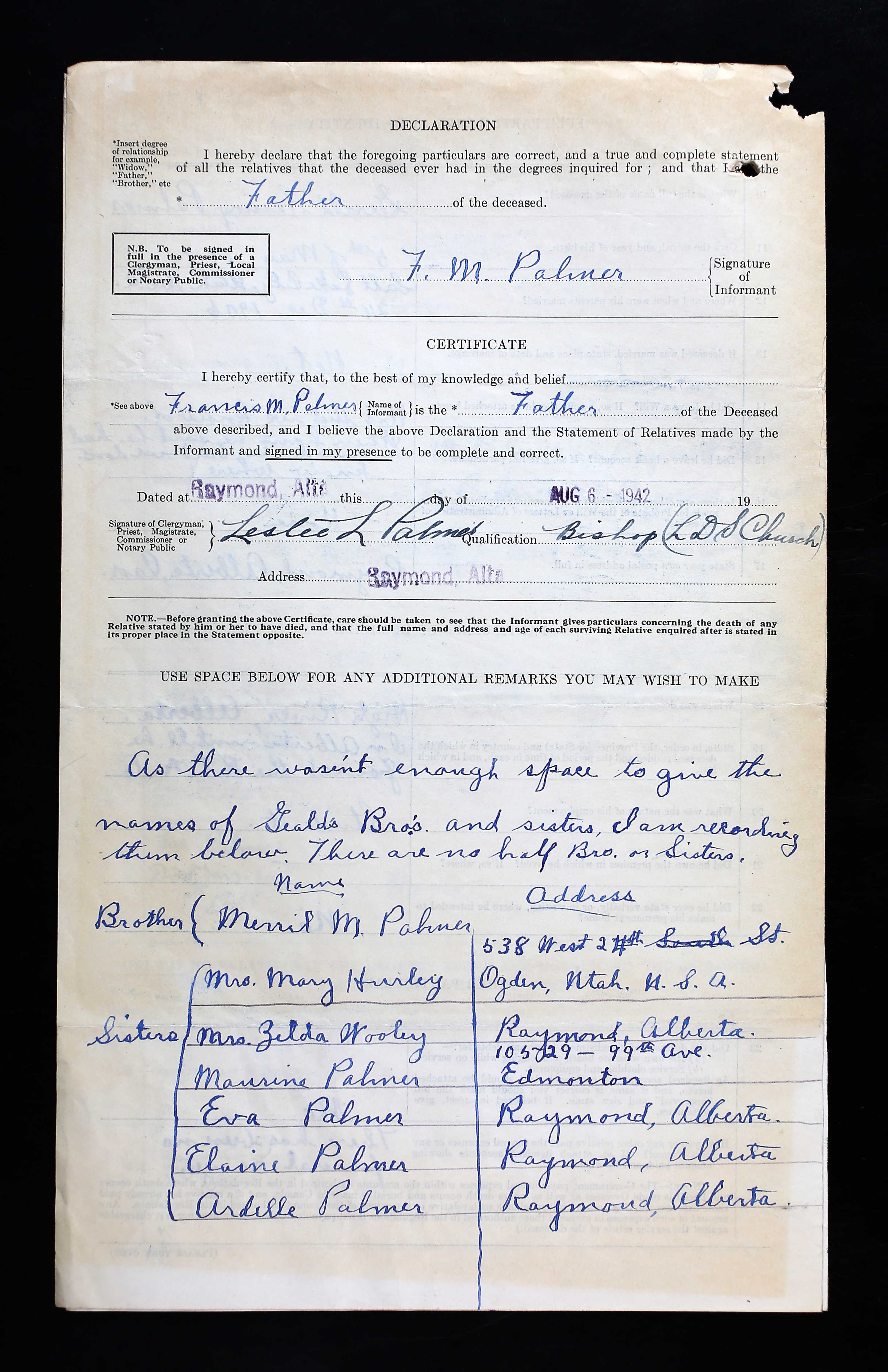

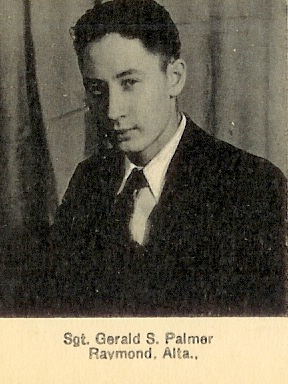

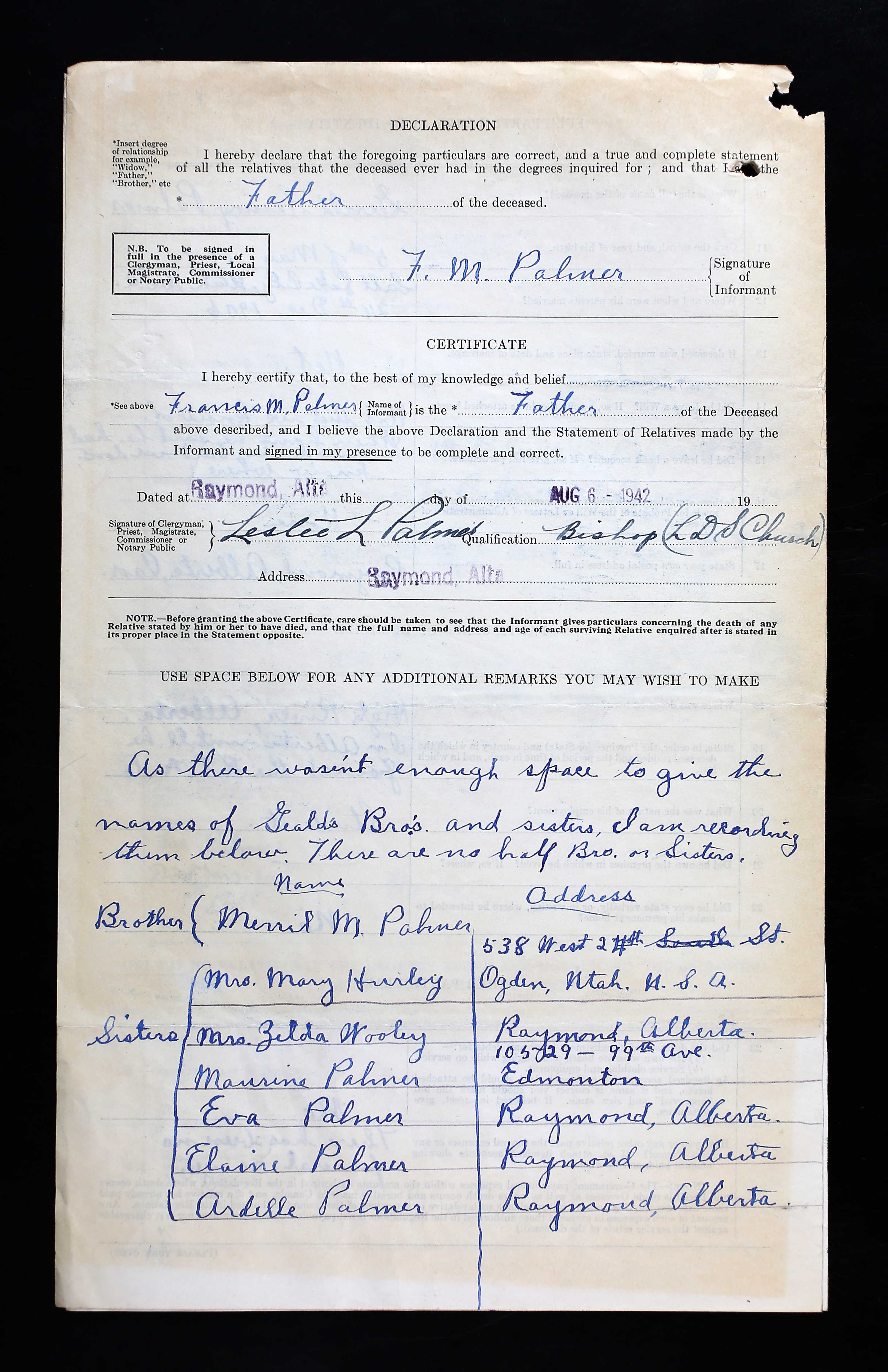

Gerald Searing Palmer, born in High River, Alberta, was the son of Francis Marion Palmer (1886-1969) and Carrie (nee Lee) Palmer (1885-1956). He had six sisters: Mary Amanda (1907-1964), Zelda (1910-2004), Carrie Maurine (1915-1995), Eva Audrey (1922-2018), Elaine, and Ardelle, plus two brothers: Merrill Marion (1912-1975) and Doyle Lee (1917-1938). The family was Mormon, living in Raymond, Alberta.

Gerald worked as a printer with Raymond News, an electrician/steam fitter with the Government of Alberta and did tractor work for S. Williams prior to his enlistment with the RCAF on July 14, 1939, in Calgary. He was taking a correspondence course in air conditioning. He stood 5’ 11 ½” tall and weighed 150 pounds. He had hazel eyes and dark brown hair. Distinctive marks included an appendectomy scar and a brown mole, medial aspect left arm. He liked softball, baseball, and hockey, playing on school teams. “I am a non-smoker.” Electricity, guns, and wireless radio were noted as hobbies.

Gerald thought he would make a good fabric worker with the RCAF. He enlisted with the RCAF for training as a tradesman. He hoped to be an electrician after the war.

His father indicated that when Gerald was home, he had a bank account, but they did not know where. Mrs. Palmer was the sole beneficiary to his estate.

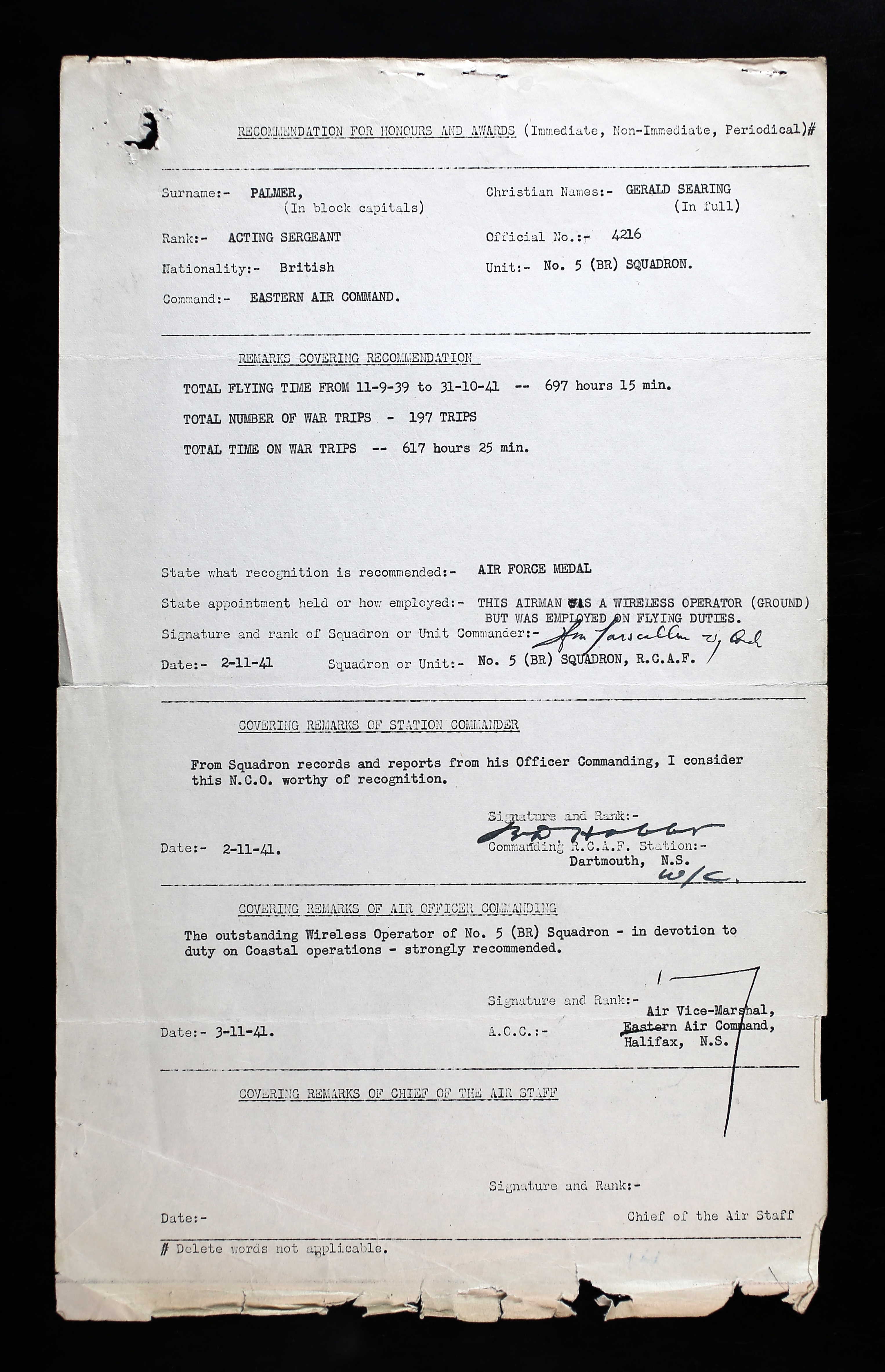

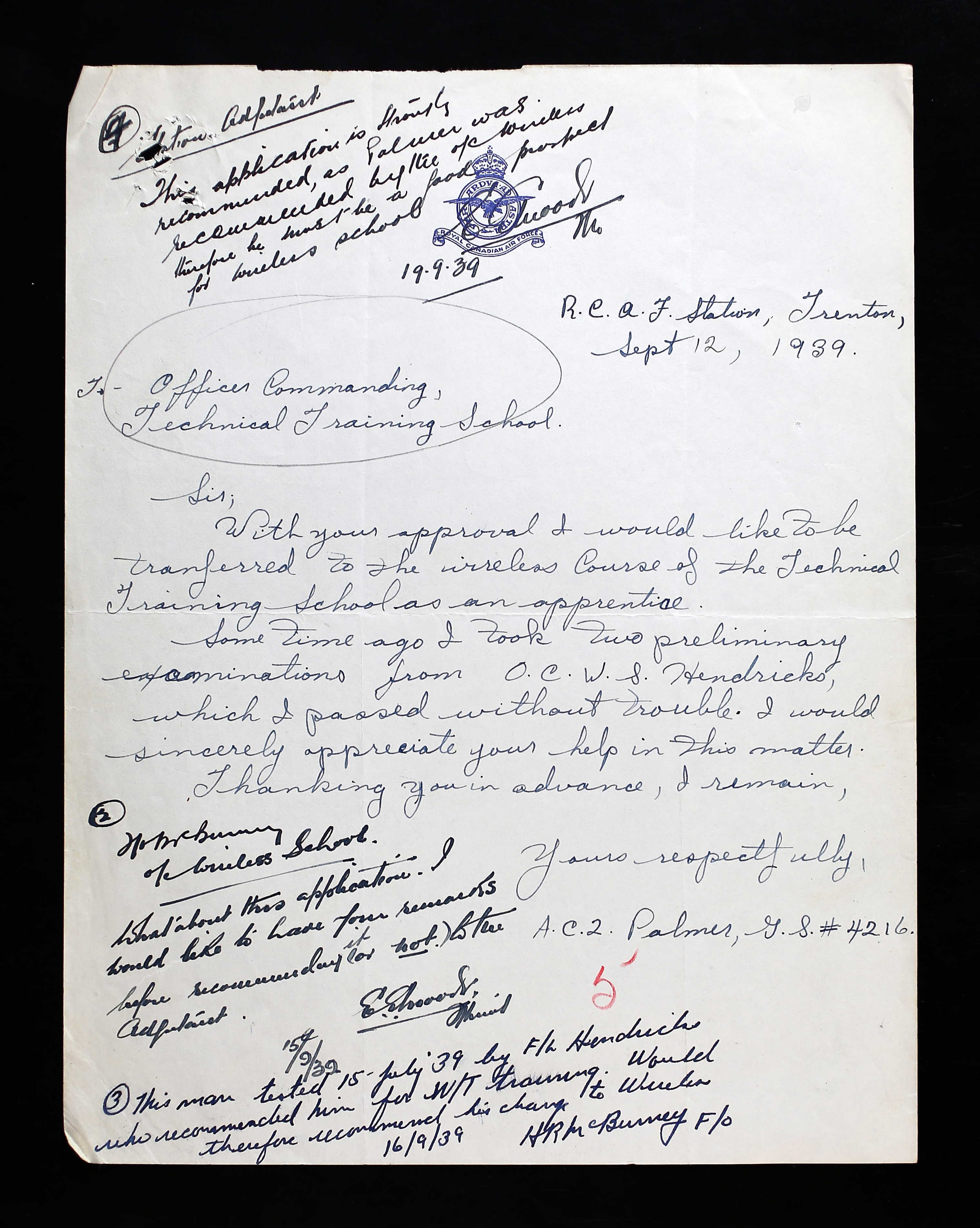

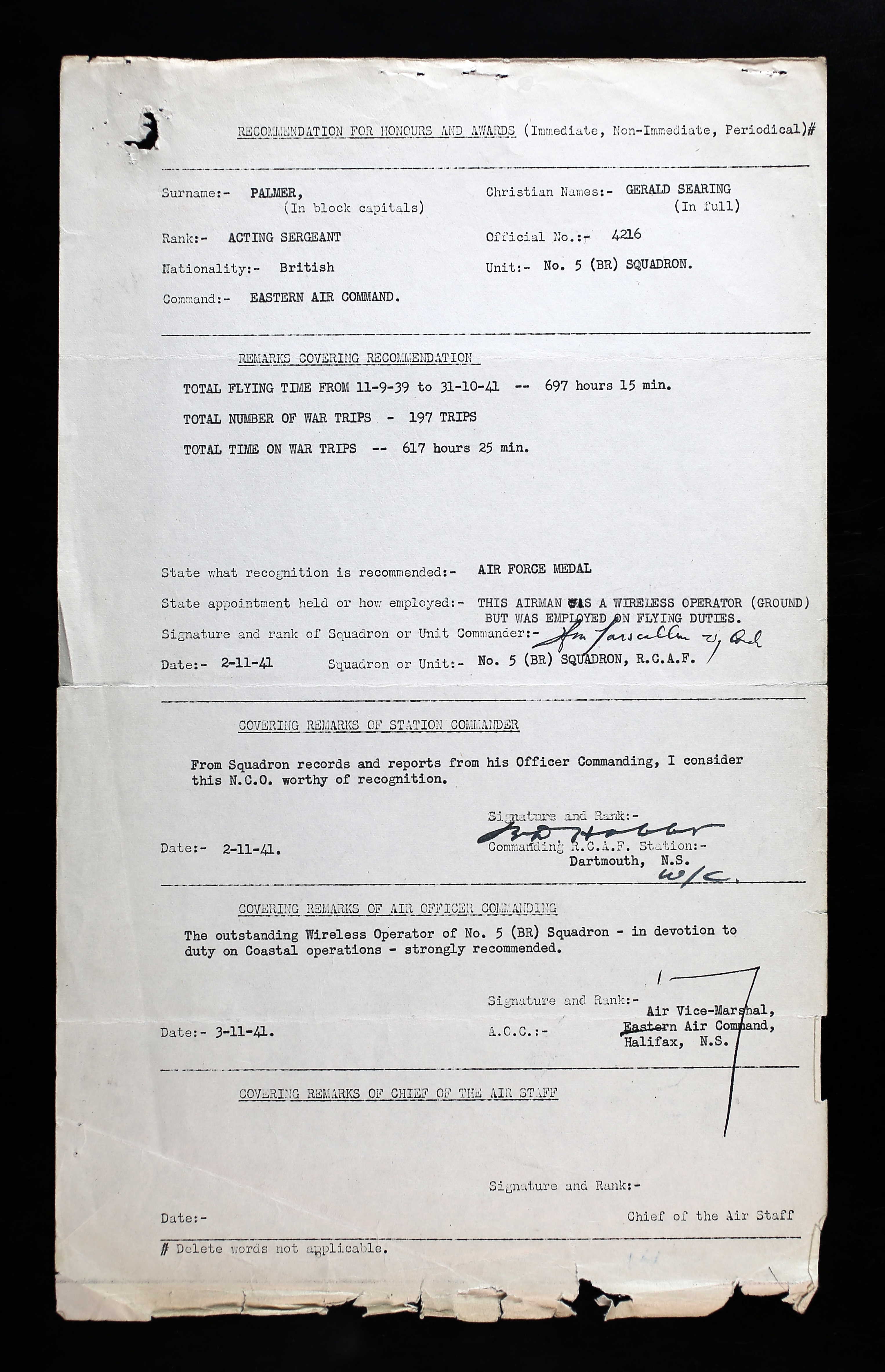

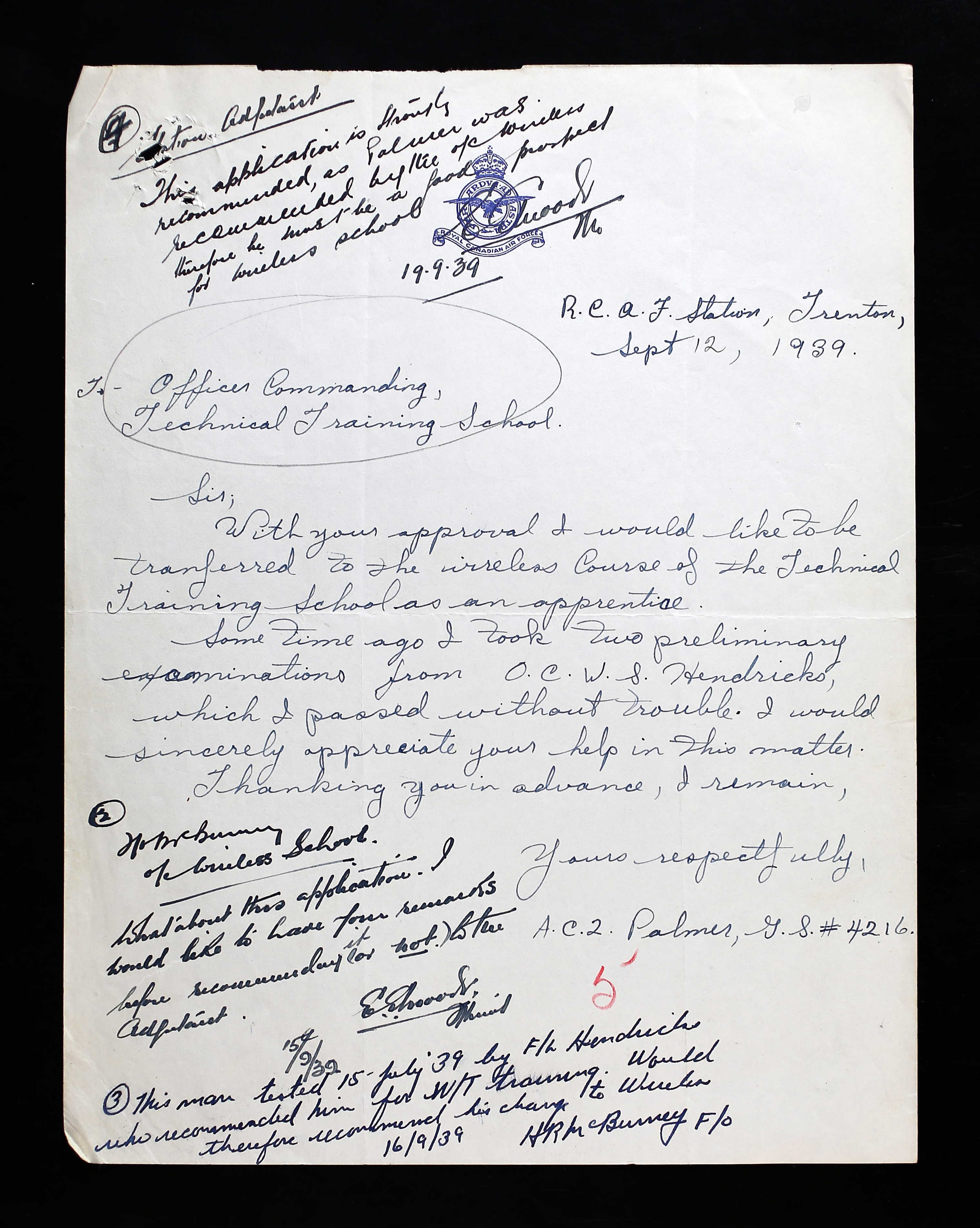

He started in Trenton, Ontario. In September 1939, Gerald requested to be transferred to the wireless course at the Technical Training School as an apprentice. He was sent to No. 1 Wireless School, Montreal, Quebec, February 1940 until April 1940. He was then sent to No. 5 BR Squadron, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. He started as a fabric worker, then a Wireless Electrical Mechanic, then Wireless Air Gunner by October 1, 1940. Gerald was a wireless operator (ground) but was employed on flying duties.

On December 15, 1941, his character assessment was “very good,” and his trade proficiency was rated “satisfactory.”

On November 2, 1941, a note from W/C of RCAF Station, Dartmouth, “I consider this NCO worthy of recognition. Total flying time from September 11, 1939 to October 31, 1941: 697 hours 15 minutes. 197 trips; total time on war trips: 617 hours 25 minutes.”

On November 4, 1941, Stranraer 946 was lost as the airplane and crew headed towards the BC coast from a stop at Penticton, BC hitting a snowstorm.

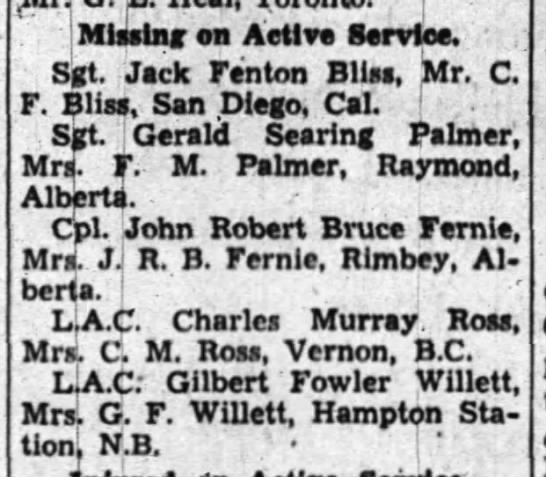

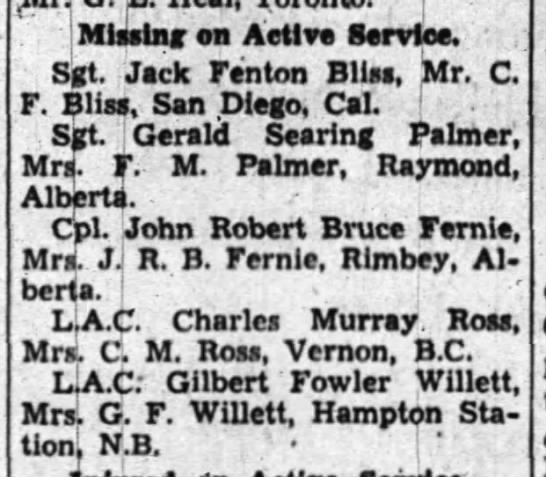

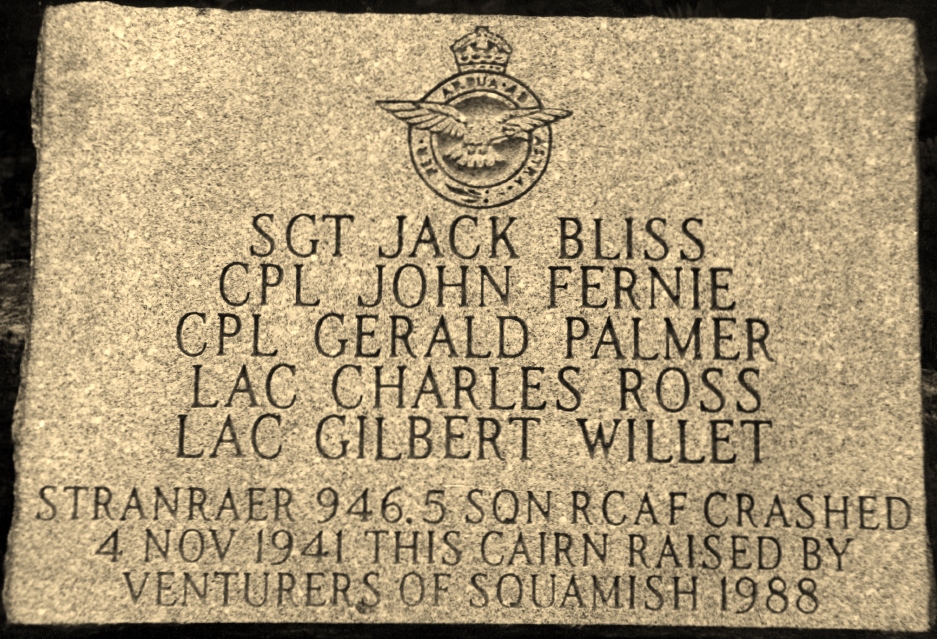

Crew: *Bliss, Jack Fenton, Sergeant, R58599, *Palmer, Gerald Searing, Sergeant, C4216 *Fernie, John Robert Bruce, Corporal, R50490 *Ross, Charles Murray, Leading Aircraftman, R65863 *Willett, Gilbert Fowler, Leading Aircraftman, R65048

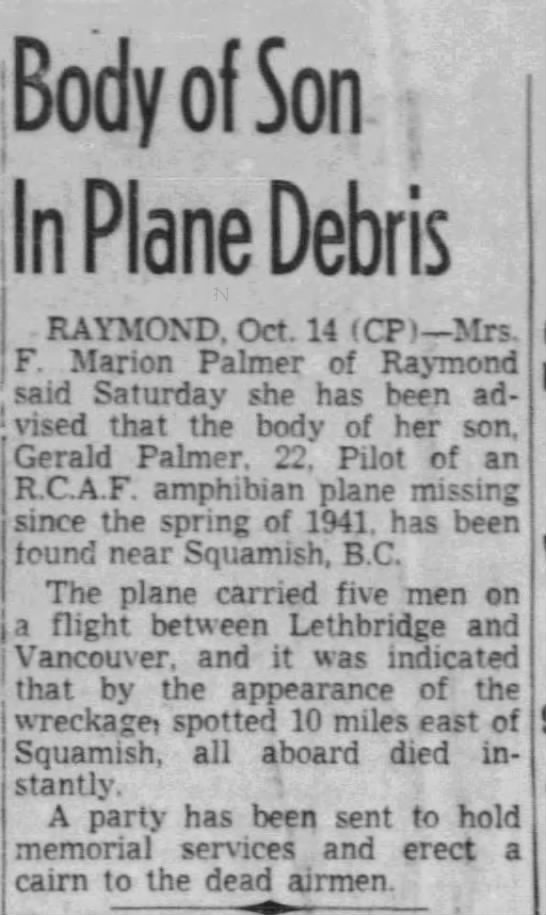

From Find a Grave: “Gerald Searing Palmer joined the RCAF at a young age. In 1941 he and his crew were delivering a seaplane from Toronto to Vancouver. They had engine trouble and landed at Newall Lake near Brooks, Alberta. After repairs were made, he phoned his parents and said he would fly over Raymond on his way to the Coast, which he did. When over the Rocky Mountains and near their destination he radioed that they had hit a terrible storm and were trying to make it to safety. He was never heard from again. Six years later the wreckage of the plane was found on the top of Baldwin Mountain. Boy Scouts in 1988 climbed to the site and erected a cairn in their memory.”

On November 25, 1941, a letter, written by G/C F. V. Heakes for Chief of the Air Staff was sent to families of the men aboard Stranraer 946. “It is with deep regret that we have to advise you in reply to your letter of November 18, 1941, that the Stranraer aircraft in which your son…was lost while en route from Penticton BC to Patricia Bay, Vancouver Island, British Columbia is still missing…the journey on which the aircraft was lost was a very short one, particularly as the longest and most difficult part of the trip was from Ottawa had already been completed. The aircraft was in radio communication with the range to Hope British Columbia but lost communication at about that point. It was apparently later seen over Vancouver Island, only a short distance northwest of its final destination. During the time the aircraft was en route from Penticton, the weather on the coast had badly deteriorated and visibility had become very poor. For this reason, other aircraft of this type had returned to base and it would seem fairly certain that the aircraft seen was the one which is missing.

The aircraft carried fuel for a minimum range of 600 miles and for this reason search for it has proceeded a distance of several 100 miles up and down the British Columbia coast, all of the inlets and inland waterways and out to sea. Additionally, the search has covered the mainland, Vancouver Island, and the northern inland region of the United States. Not only have our own aircraft searched but the United States Air Service has have also assisted by having their aircraft cover wide areas for us. Naval vessels have also collaborated in the search. The search is still being conducted and every rumor is being followed up in the hope a successful end might be made to our efforts. The aircraft was new and in perfect condition, while the pilot was experienced on this type and had flown at operationally on the coast. Aviation has unhappily always presented those engaged in it with problems of this kind, and while every effort and precaution is exercised to ensure safety of personnel and aircraft, these efforts sometimes fail. Where they do fail, as in this case, it is natural that relatives of men missing should feel concerned as they ordinarily have little knowledge of the organization that exists to ensure safety of aircraft and to render aid when necessary. You may be reassured that no effort to discover this last aircraft has been or will be spared.”

In early May 1942, Mr. Palmer wrote to the Department of National Defence, Air Service, Estate Branch: “…Since it has been over six months since my son was lost, I would like to know if you have had any further news from the plane or any member of the crew. Also, if it is necessary to wait longer for settlement of his affairs.”

Mr. Palmer wrote many letters to the Estates Branch to settle his son’s estate. In June 1942: “…only a small % of reserves amounting to about $48 on this [insurance] policy. You will note that on the front of this policy, it states that this policy is placed in the special mortality class and extra premium charged. If this company is allowed to charge our boys in the Armed Forces extra premiums and then stick on a clause exempting them from paying in case of death while on duty, the Government should do something to protect our boys from this graft. I know our son thought these policies would be paid if he lost his life while on duty, for he told us so. Gerald wasn’t on Patrol duty but was helping ferry a plane from Montreal to BC. We have another policy of his with the same company worded about the same. If you wish it, we can send it to you. Please look this policy over and see if you can help us collect for these policies. Also will you settle our son’s estate as soon as possible. Please send us our son’s will and a death certificate. Please return policy when thru with it. Hoping you will give these matters your immediate attention. You will note the policy is made payable to my wife.”

Mr. Palmer wrote another letter in July 1942, asking for an update on his requests from June. “It has been three months since you reported our son officially dead, and you haven’t done a thing about it. Please let me hear from you.”

In October 1942: “You stated you ordered our son’s personal effects be sent at once to your office and you would send them to us at once. Also, the balance of pay and any other moneys due our son would be sent in the near future to his mother, according to his will. It has been two months and we haven’t heard anything more from you. It has been about a year since he lost his life and six months since he was officially declared dead. We expect you to let us know at once why all this delay. We know your department is busy, but six months should be more than enough time to settle this estate where there is a will and very little to settle. I hope you will be good enough to answer this letter at once.” In November 1942, Mr. Palmer wrote to the RCAF Estates Branch, Ottawa. “…You say you haven’t been able to locate where our son had any money on deposit…In going through his diary, he says, ‘On February 9, 1940, I have deposited $50 in Post Office Savings Account.’ And in the back of his book, he gives his PO Savings Account Bank Book No. as 3526 ½. He doesn’t say if he had added to this account or withdrawn it…but you will no doubt know what the letters PO stand for. So will you kindly try and locate this account.”

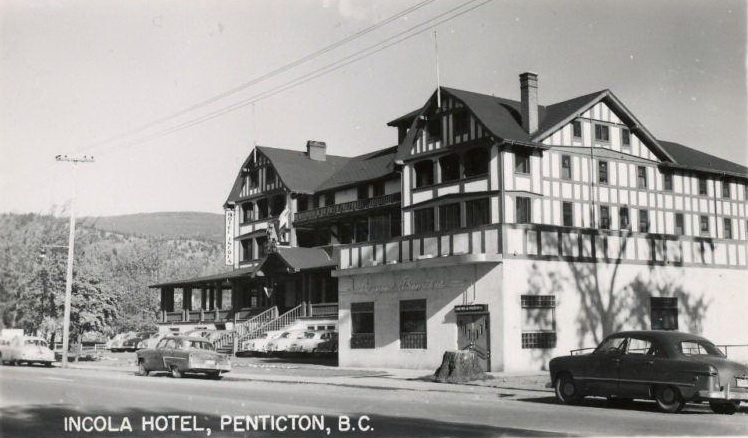

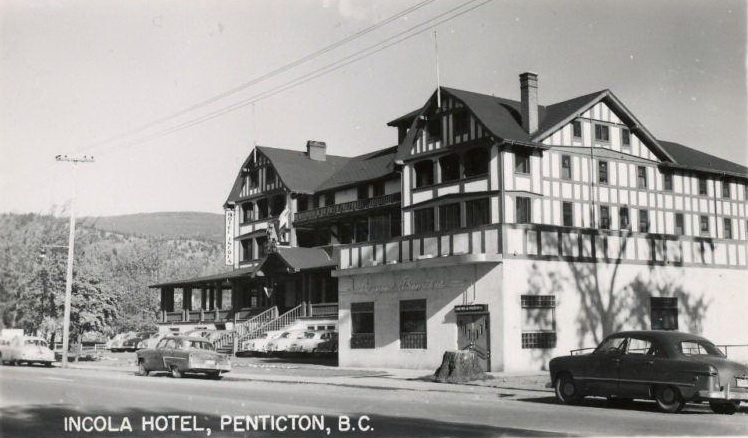

In October 1943 Mrs. Palmer wrote, “Re: your letter of October 19th. I cannot understand why the Hotel Incola should wait for two years to send you their statement for our son’s account or why the Government of Canada should ask me to pay his account while being in the service of his country and giving his life. So I don’t consider myself under any obligation to pay the enclosed statement.” [Hotel Incola was a luxury hotel constructed by the CPR in Penticton, BC, opening in 1912, closed in 1979, demolished in 1981.]

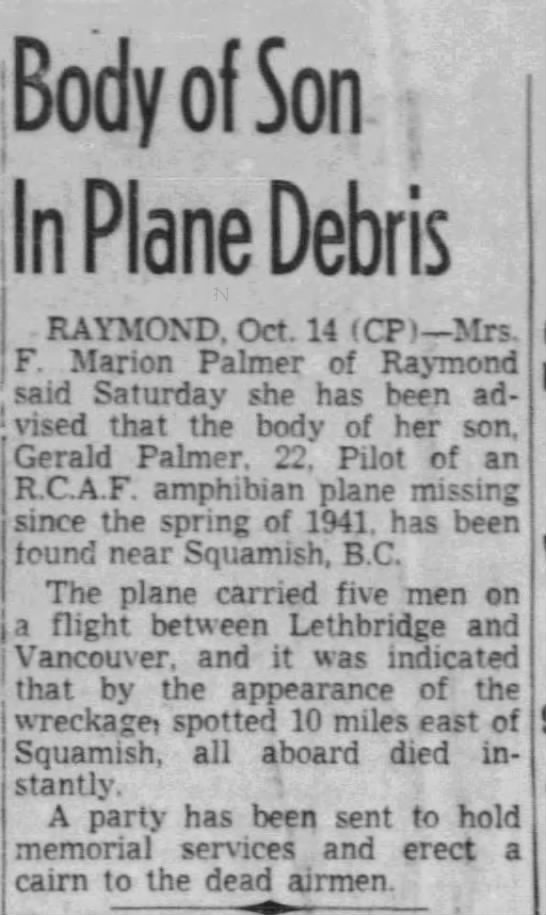

In October 1947, the plane was located by prospector Basil Zurbriggen. [Interestingly, he had been considered missing in September 1947.]

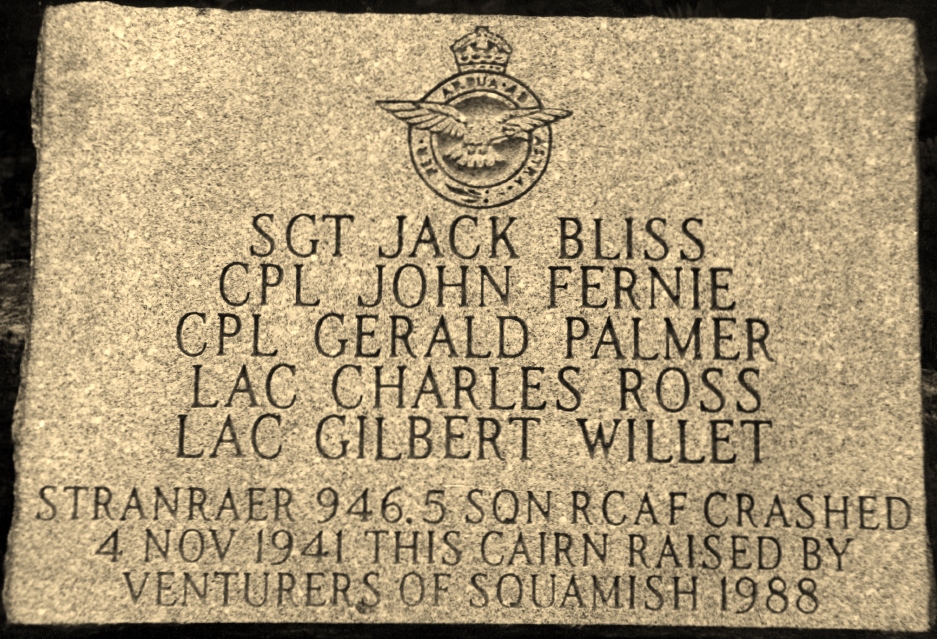

Jerry Vernon, CAHS Vancouver Chapter President wrote on the RAF Commands Forum in 2011 indicating that a cairn was built at the site, approximately ten miles southeast of Squamish, British Columbia. The airplane flew into the hillside at the end of Indian Arm between Indian Arm and Squamish. “Any logging roads into the site were washed out long ago. The aircraft just caught the top of the ridge, otherwise they would have been over the top and looking at Howe Sound in the distance. There is a wooden cross at the crash site with the names of the crew, but vandals had partially burned it.” Details: “Reading some of the detail on 946....it had left RCAF Stn. Rockcliffe on 07 Oct 41. There was a change of pilot at Regina on 18 Oct 41, when F/O Coburn came down with acute appendicitis. Sgt. Jack Bliss took over as pilot. They landed at Brooks, Alberta, on 21 Oct 41 and bought gas from the Brooks Garage. One wingtip was damaged on the end of the CPR pier at Penticton on 23 Oct 41, and this took 12 days to repair. The aircraft departed from Okanagan Lake in poor weather on 04 Nov 41. At 1300 hrs, the aircraft reported that they were ‘SE of Vancouver in the North Sector of the Princeton Range, flying blind and descending to try and make contact with the ground.’ They were advised to remain at 11,000 ft. until they had crossed the Vancouver cone marker. At 1346, the last radio messages from the aircraft said that ‘We are lost in a dense snowstorm over land and are nearly out of fuel. No position can be decided.’ A large scale search was conducted, particularly in the Port Alberni and Mount Arrowsmith areas [Vancouver Island], as an aircraft had been heard in that vicinity. The search was discontinued on 27 Nov 41. The plane was found in heavy timber on 06 Oct 47 by an old trapper by the name of Zurbriggen. A cairn was erected, and a memorial service was held for the five lost airmen.”

In late October 1955, families received a letter from W/C W. R. Gunn, RCAF Casualties Officer, for Chief of the Air Staff who indicated that their sons did not have a known grave and their names would appear on the Ottawa Memorial.

In the spring of 1986, the Hellcat Venture Company erected a monument to replace the deteriorated cross. Money was raised to place a memorial plaque in 1988. In 2012, a book was published to commemorate the men lost aboard Stranraer 946. See links below.

LINKS: