May 16, 1919 - April 22, 1943

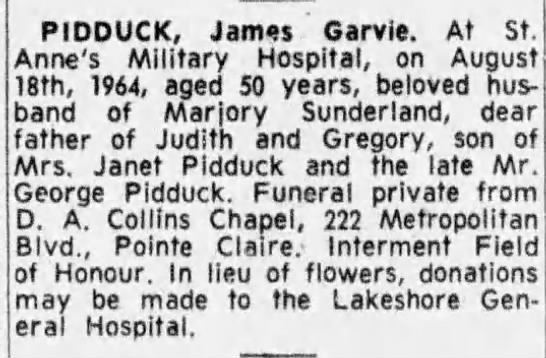

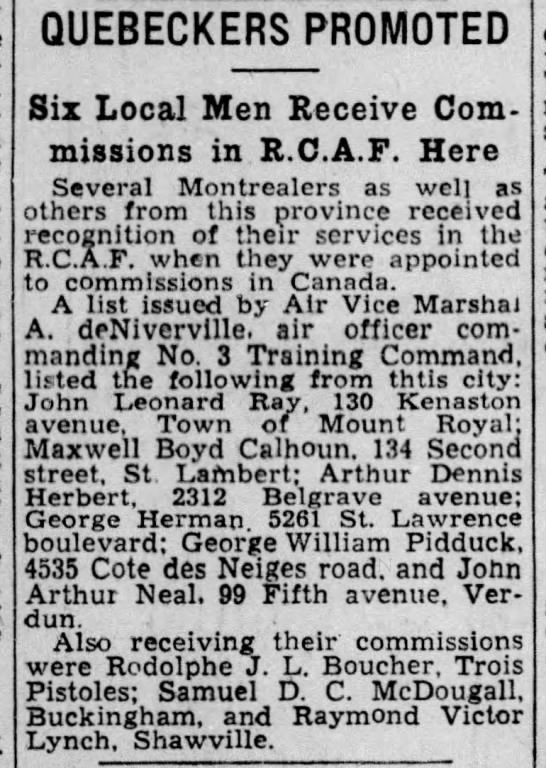

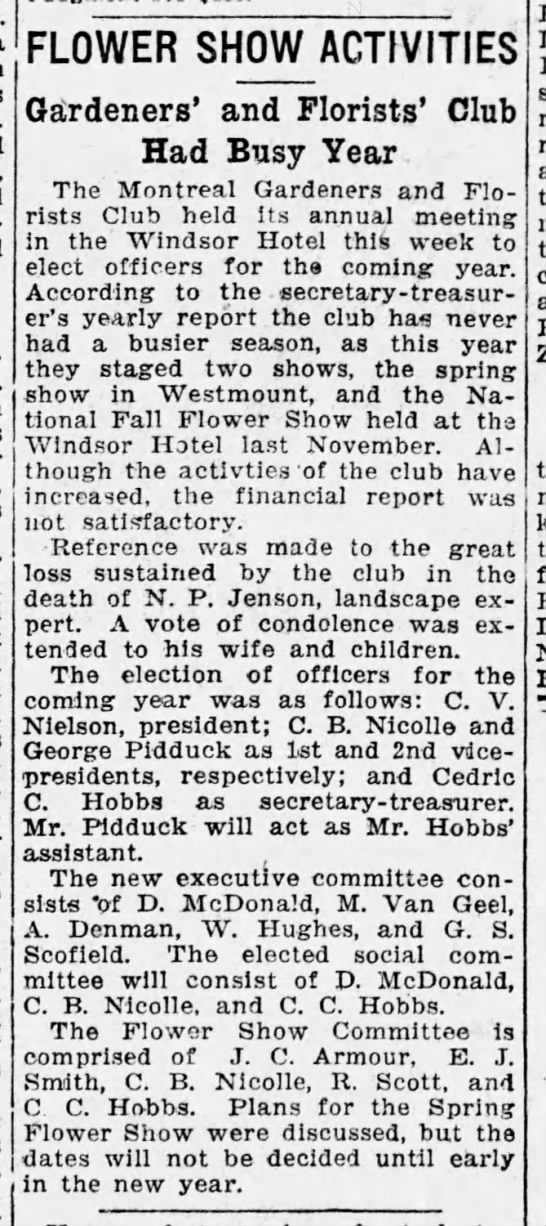

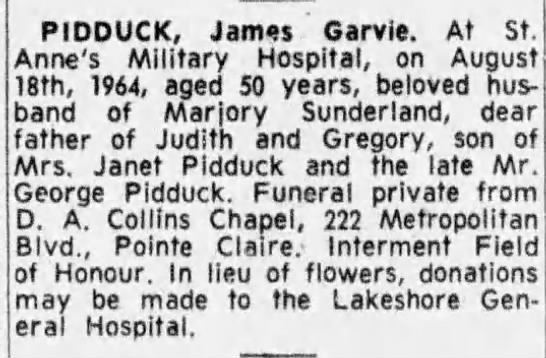

George William Pidduck, born in Montreal, was a son of George William Pidduck (1890-1955), florist, and his wife, Janet Richardson (nee Garvie) Pidduck (1892-1970). He also had one brother, James (1914-1964), who also served with the RCAF. The family was Presbyterian. George attended school in Scotland from 1924 to 1933, finishing his education in Montreal in 1937.

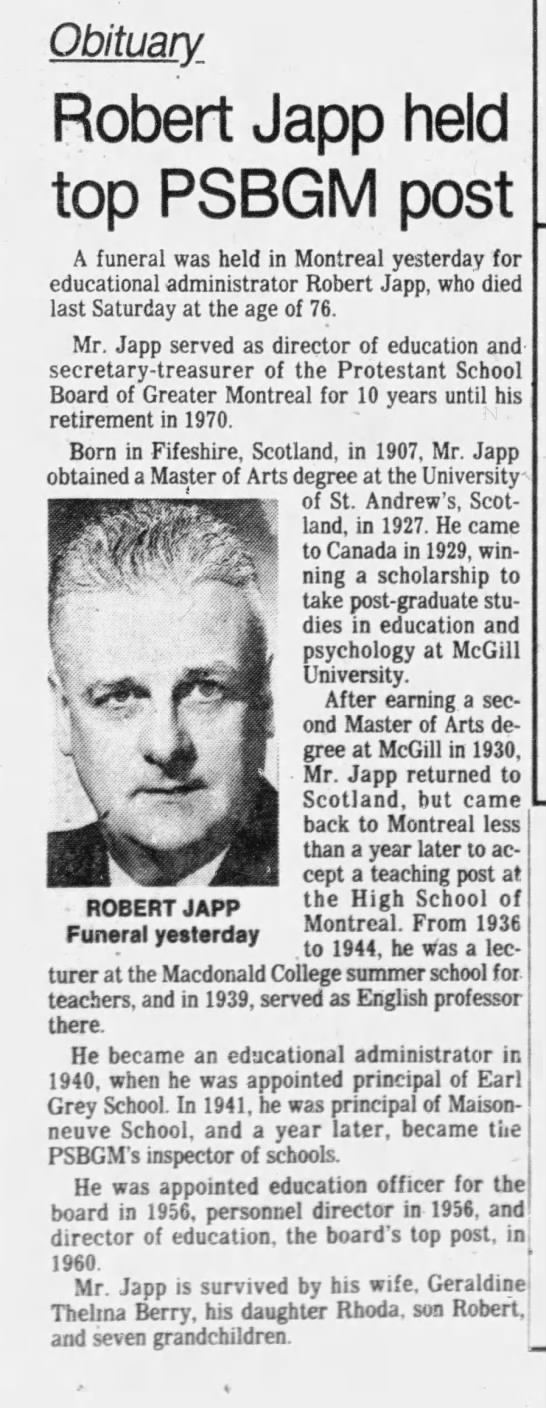

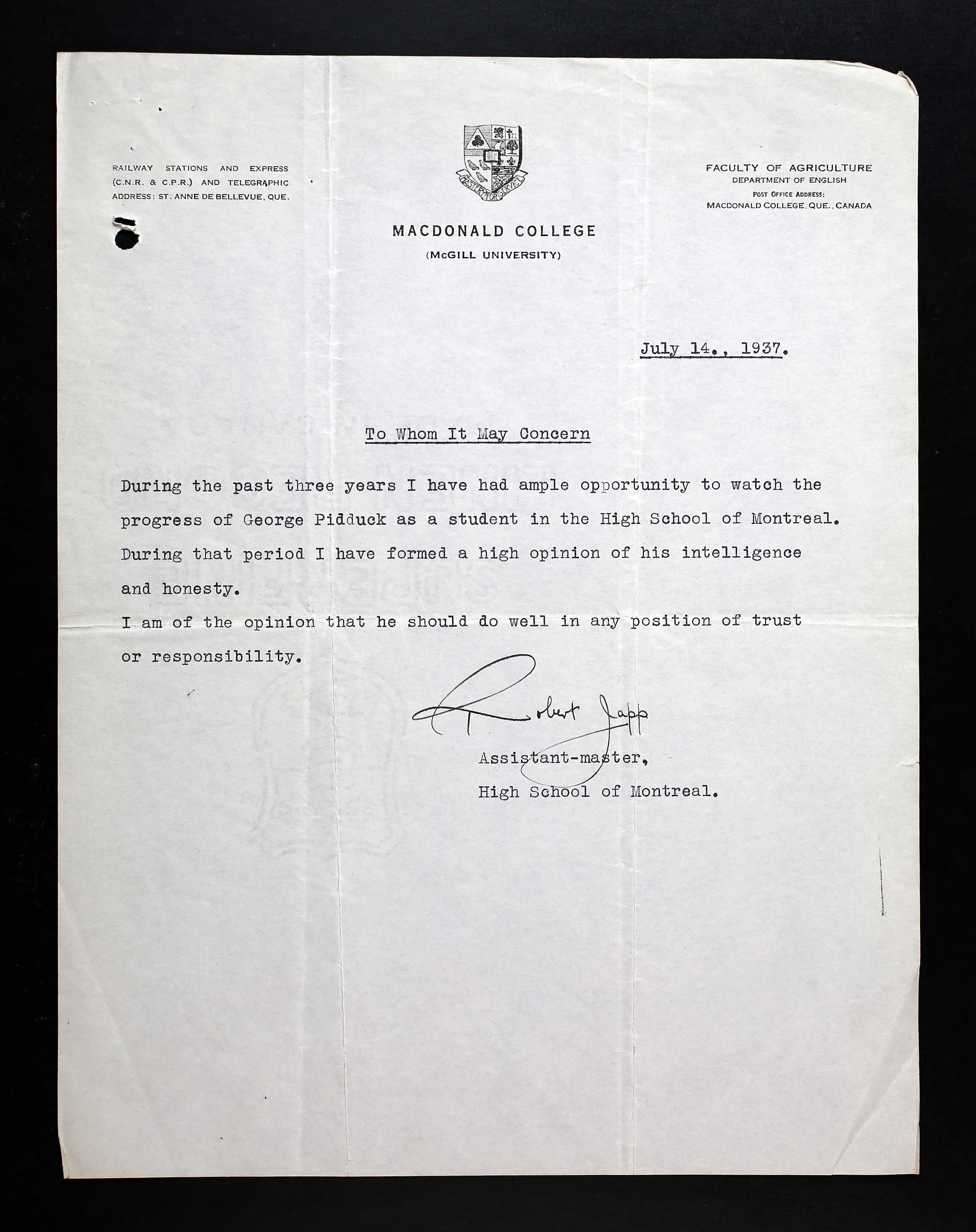

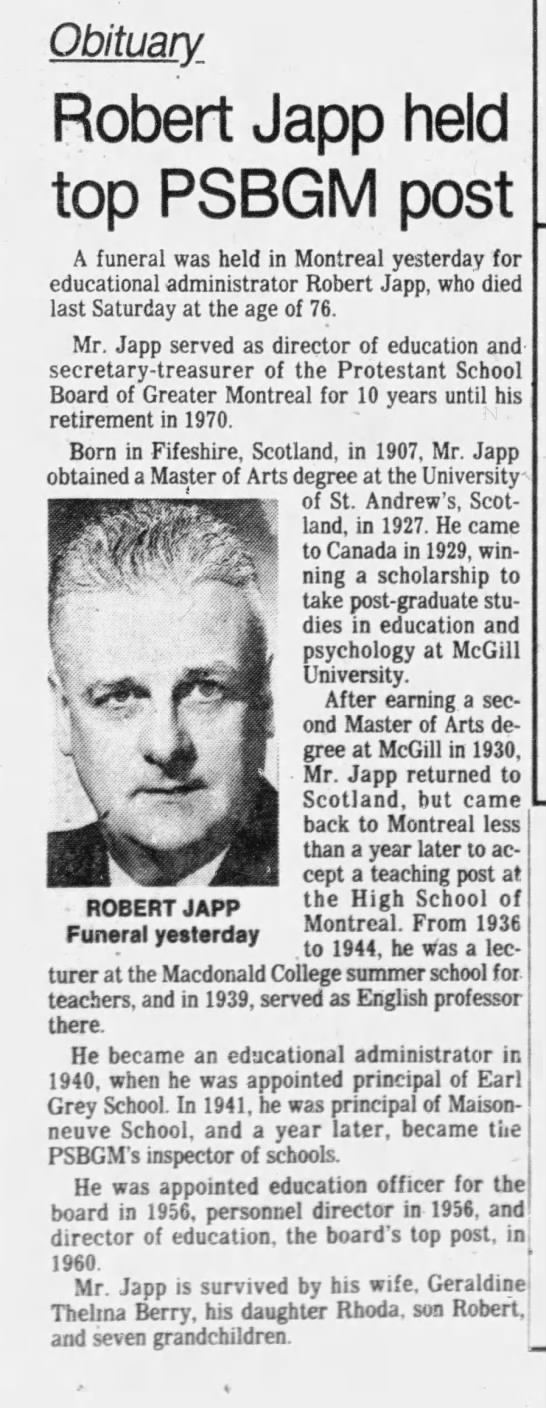

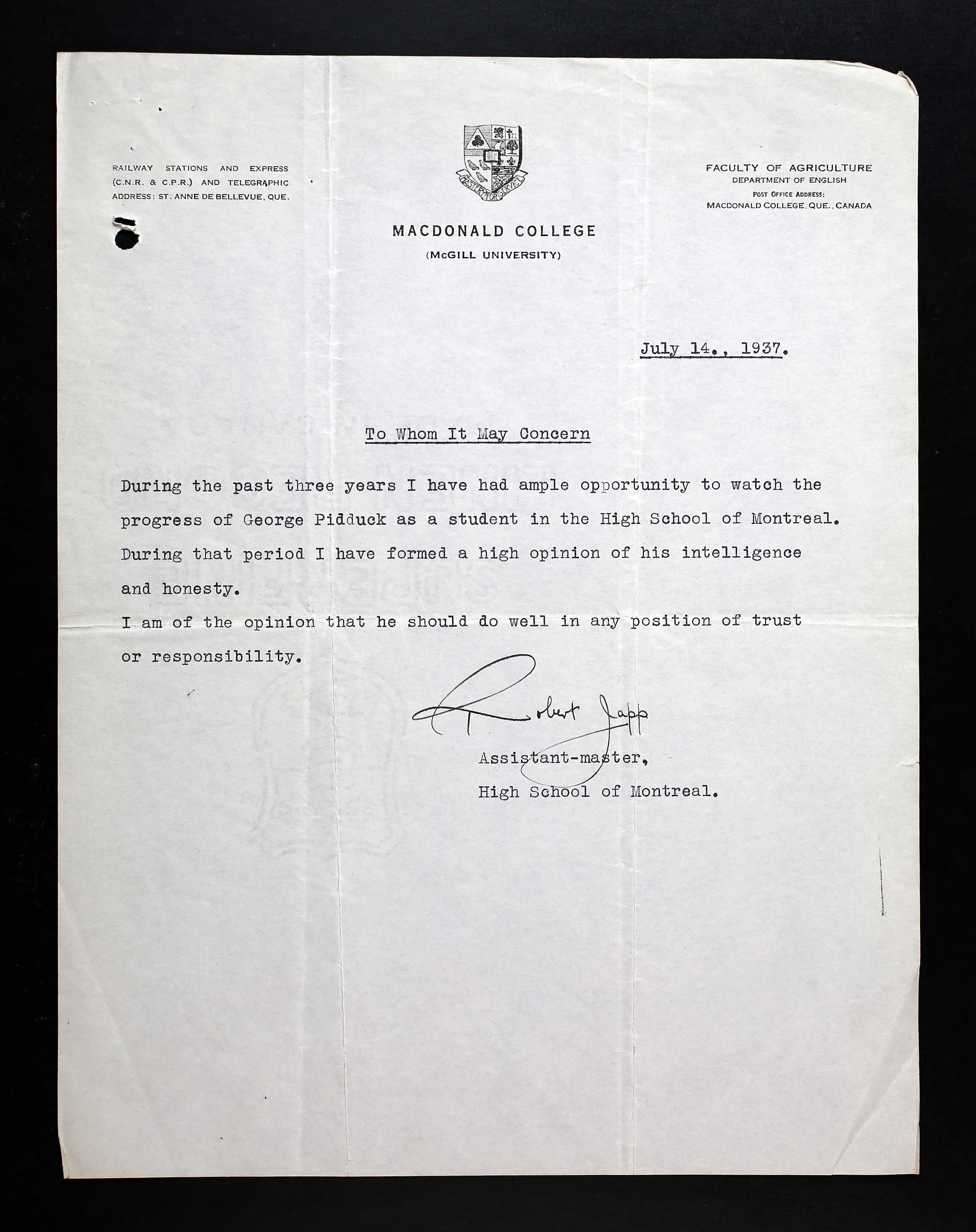

In July 1937, George received an excellent reference letter from Assistant Master, Robert Japp, Macdonald College (McGill University). “During the past three years, I have had ample opportunity to watch the progress of George Pidduck as a student in the High School of Montreal. During that period, I have formed a high opinion of his intelligence and honesty.”

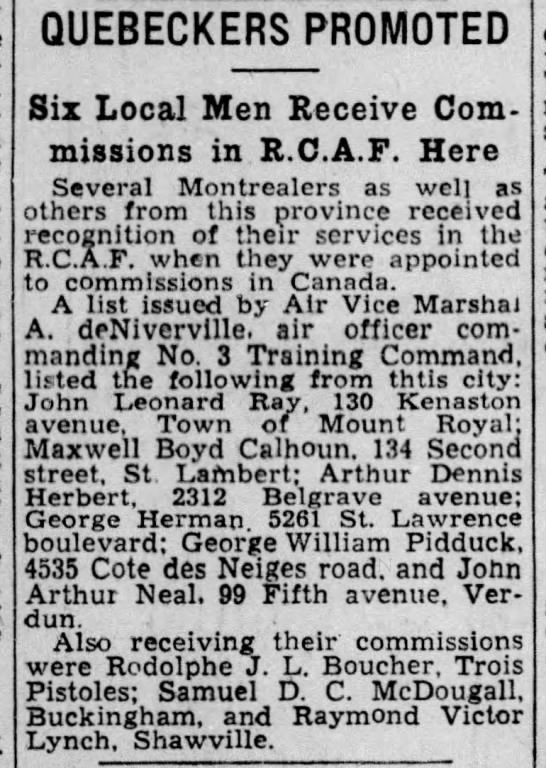

George enlisted at Training Centre No. 21 with the Canadian Army on October 9, 1940, living in Toronto, Ontario at the time. He was working as a salesman for Burt Business Forms Limited. Prior, he was a teacher at a horse-riding school for one year. He indicated he had preferred to serve in the Air Force. He had dark brown eyes, dark brown hair, stood 5’ 7 ½” tall, and weighed 154 pounds. He had acne on his chest and on his back.

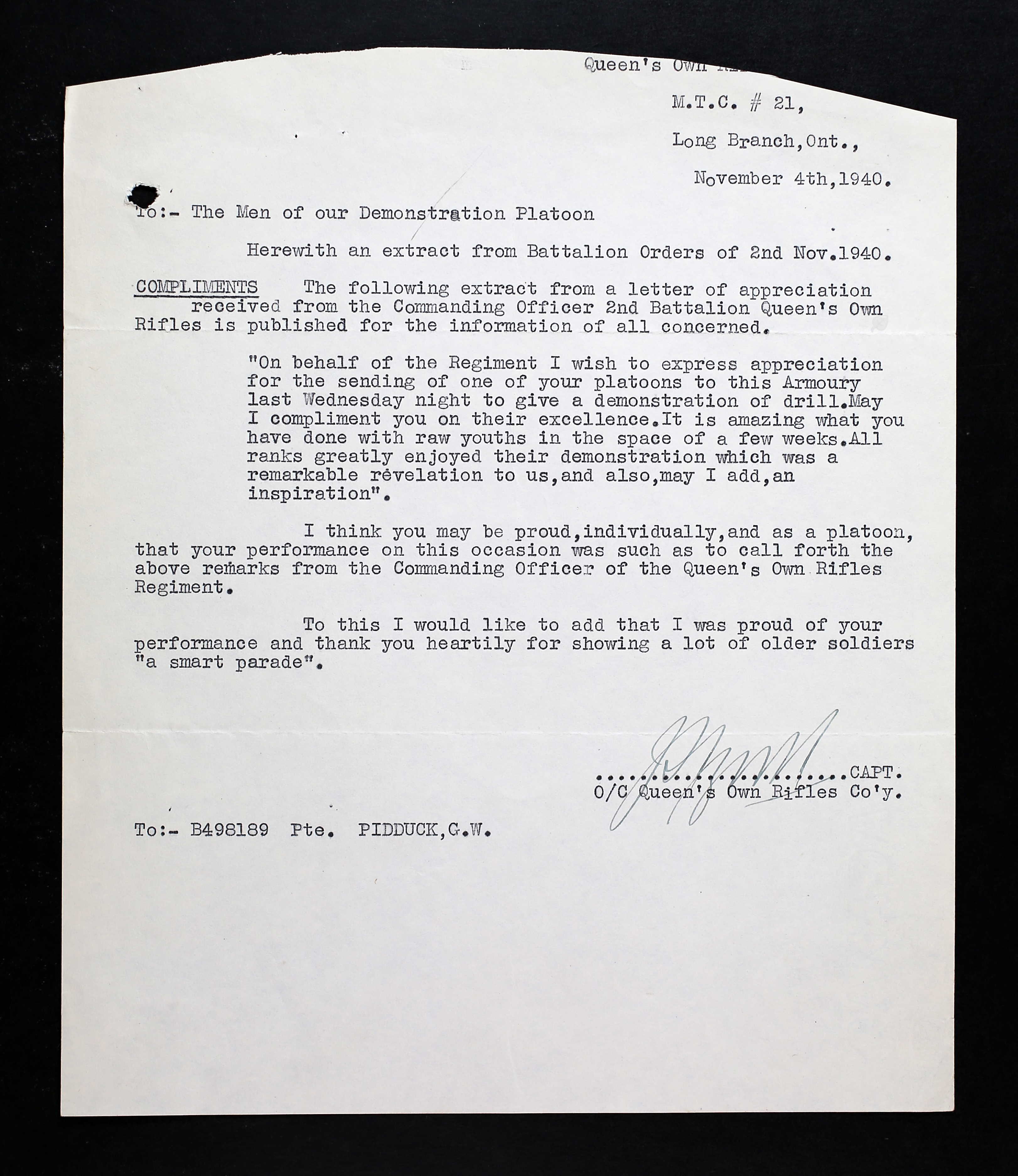

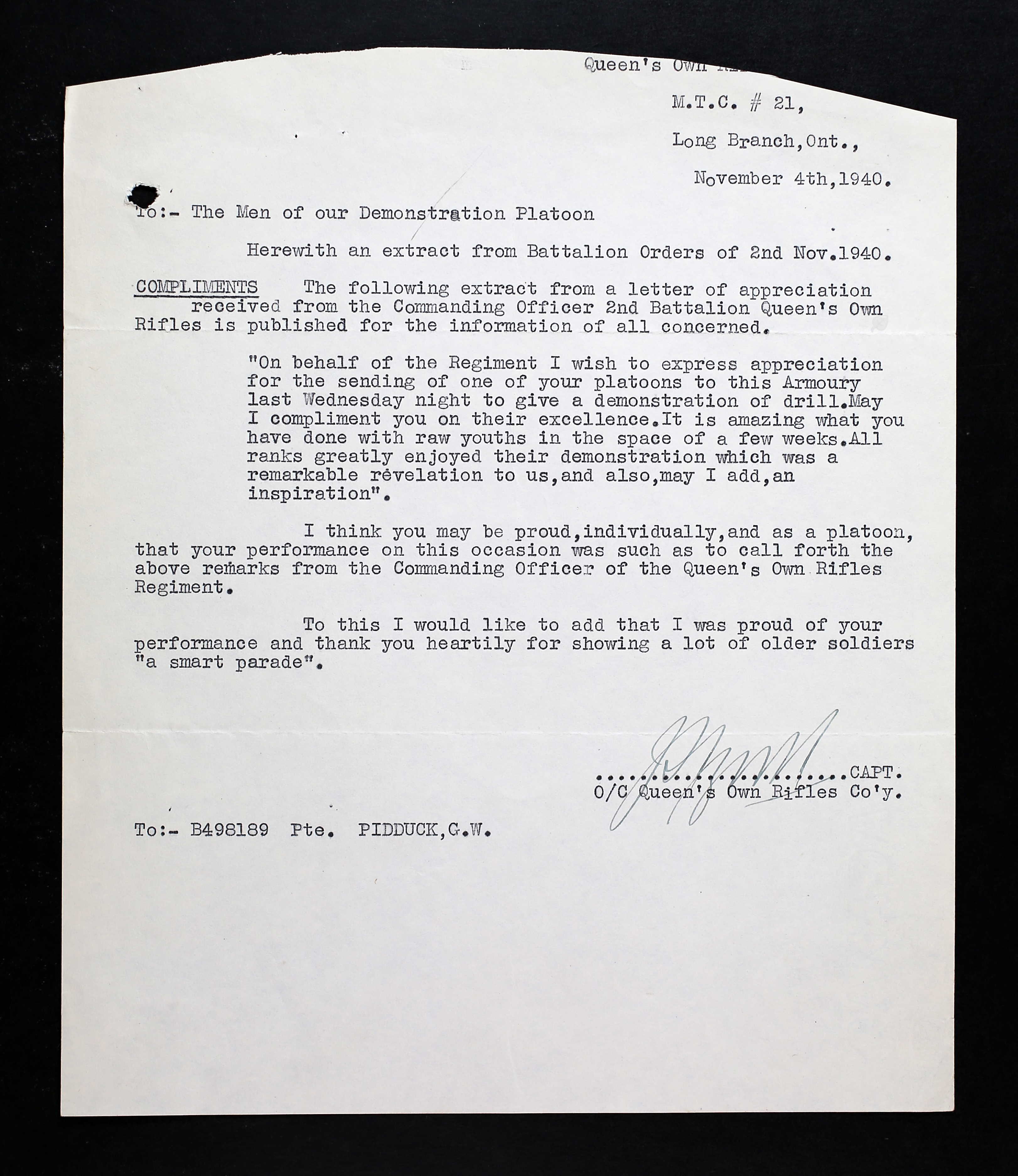

On November 4, 1940, an extract from the Commanding Officer of 2nd Battalion Queen’s Own Rifles of November 2, 1940 to the men on the Demonstration Platoon Long Branch, Ontario: "On behalf of the Regiment, I wish to express appreciation for the sending of one of your platoons to this Armoury last Wednesday night to give a demonstration of drill. May I complement you on their excellence. It is a mazing what you have done with raw recruits in the space of a few weeks. All ranks greatly enjoyed their demonstration which was a remarkable revelation to us, and also, may I add, an inspiration." George’s captain added, “I think you may be proud, individually, and as a platoon that your performance on this occasion was such as to call forth the above remarks from the Commanding Officer of the Queen’s Own Rifles Regiment. To this I would add that I was proud of your performance and thank you heartily for showing a lot of older soldiers ‘a smart parade.’”

In the February 18, 1941 issue of the Montreal Gazette, George’s brother, James, was reported seriously injured, along with another crewmember, as the result of a flying accident at No. 4 O. T. U., in Wellington R1367 on February 4, 1941. Four of the crew were killed. James returned to Canada in December 1941, and shortly afterward, became a navigation instructor in Rivers, Manitoba.

On February 7, 1942, George applied for enlistment in the RCAF at No. 13 Recruiting Centre. “Fair A. L. score, but appears very intelligent. Very good aircrew material. Satisfactory education. Away from school four years. A perfect gentleman.” He was recommended for pilot or observer and was definitely suitable for commission. He was “fit, keen to fly, alert, intelligent, better than average in maths, four years high school. Looks excellent material for aircrew.” He obtained 71% in algebra and 67% in geometry, junior matriculation.

George listed horseback riding, swimming, skiing, golf and soccer as sports he enjoyed. He smoked twenty cigarettes a day and drank alcohol moderately. His physique was noted as athletic.

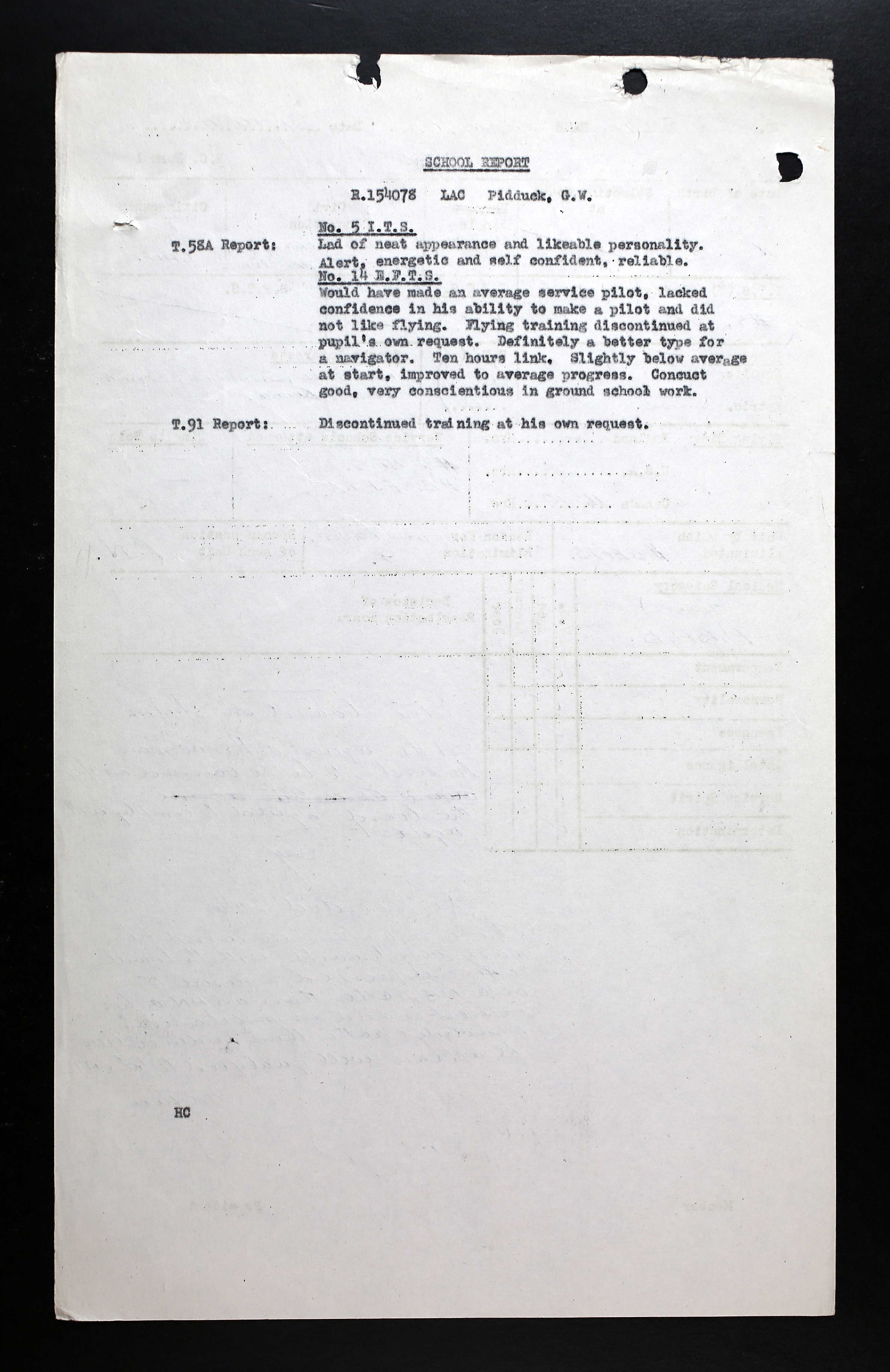

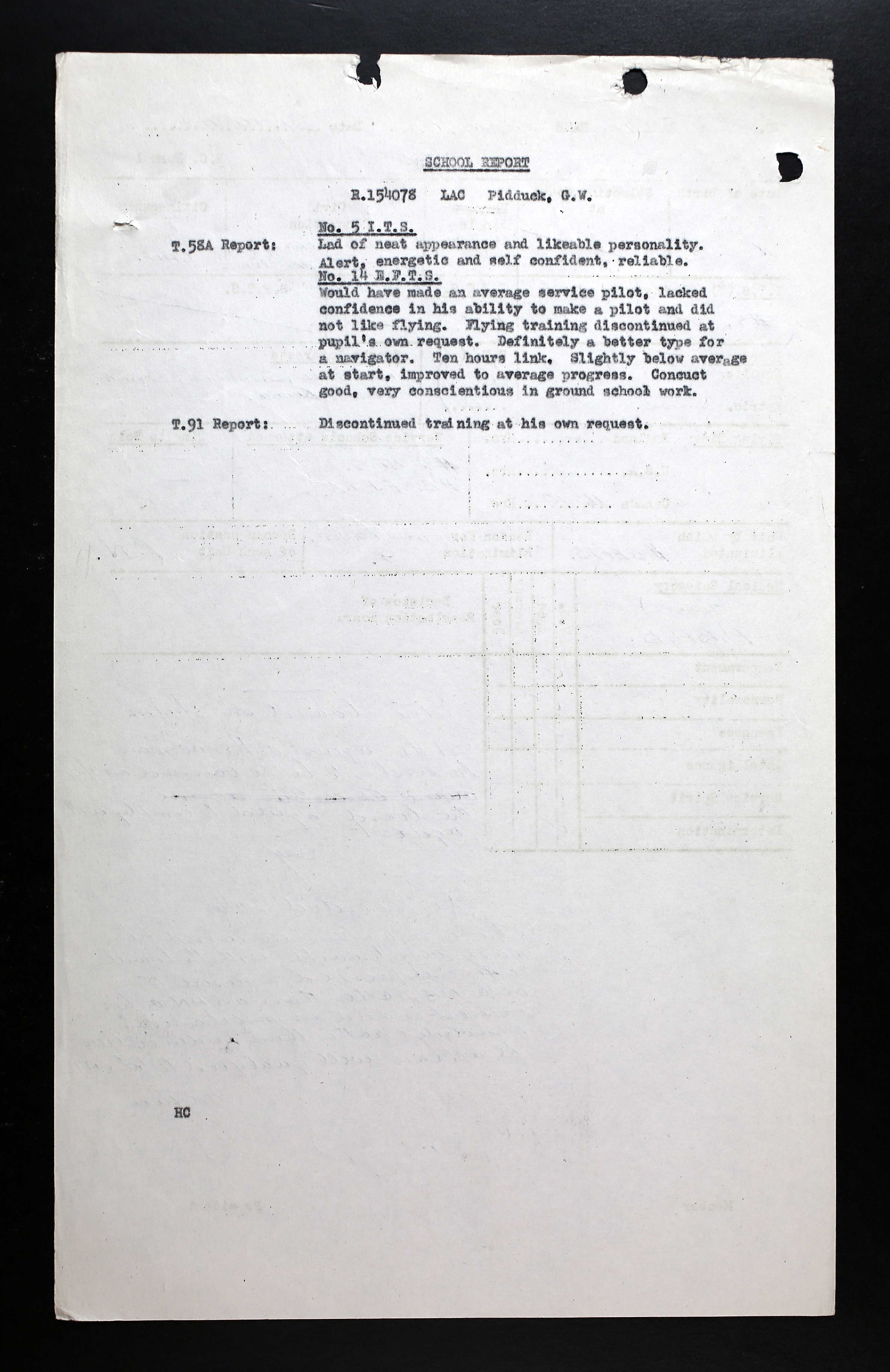

On June 8, 1942, George was at No. 5 ITS, Belleville, Ontario until August 1, 1942. He was 70th out of 146 in his class with a 75%. “Lad of neat appearance and likeable personality. Alert, energetic, and self-confident. Reliable.”He was then sent to No. 13 EFTS, St. Eugene, Ontario, September 14 until October 21, 1942, but he did not complete his training. “Would have made an average service pilot. Lacked confidence in his ability to make a pilot and did not like flying. Flying training discontinued at pupil’s own request. Definitely better for a navigator. Ten hours link. Slightly below average to start, improved to average progress. Conduct very good, very conscientious in ground school work.”

November 3, 1942: “At the request of this airman, he wishes to be re-boarded. The board agreed to comply with request. This airman has discussed his case very thoroughly with the board and has expressed a desire to an Air Bomber rather than an Air Navigator as his interest is more in mechanical knowledge than an academic view. He appears well qualified to take A.B.”

George was at No. 5 B&G School, Dafoe, Saskatchewan, on November 23, 1942 until February 5, 1943. “Above average in all bombing and gunnery work. Intelligent and confident; appears lackadaisical but is anxious to succeed as an Air Bomber.” 81.8%

Then he was sent to No. 1 Central Air Navigation School, Rivers, Manitoba, Course 68, from February 8 to March 19, 1943, training as an Air Bomber. “Handicapped by illness, but did a good job in navigation. Armament: average. General: good worker, cheerful student.” 79.5%. George was awarded his Air Bomber’s Badge on March 18, 1943. It is unknown if his brother, James, was an instructor here at the same time as George was training.

By April 4, 1943, George was at Y Depot, Halifax, awaiting transport overseas.

Sometime later, he, with 36 other RCAF airmen, boarded the Amerika. On April 22, while on its way from Halifax, Nova Scotia to Liverpool, it was torpedoed as the ship was heading to Britain. It was a straggler in convoy HX-234. Thirty-seven men, all officers in the RCAF, were presumed missing as a result of enemy action at sea including George. Their ship was sunk by U-306, south of Cape Farewell, off Greenland.

Forty-two crew members and seven gunners were also amongst those who were lost. The master, Christian Nielsen, 29 crewmembers, eight gunners, and sixteen passengers (RCAF airmen) were picked up by the HMS Asphodel, and landed at Greenock. General cargo, including metal, flour, meat and 200 bags of mail were also lost.

Mrs. Pidduck received a letter in late June 1943 from F/L W. R. Gunn, RCAF Casualties Officer for Chief of the Air Staff. "Since my letter of May 6th, no additional news has been received. Attached is a list of the names and next-of-kin of sixteen Royal Canadian Air Force officers who embarked on the same ship as your son and following enemy action at sea were safely landed in the United Kingdom. The following official statement was made in the House of Commons....’I have been in receipt of communications from a number of members of this house and from people outside with reference to rumours regarding the recent loss of a number of members of the RCAF by the sinking of a ship in the north Atlantic and I desire to make the following statement on the facts. The vessel in question was a ship of British registry of 8,862 tons, designed for peace-time carriage of both passengers and freight, and having a speed of fifteen knots. She carried a crew of 86 and the passenger accommodation consisted of 12 two-berth rooms with bath and 29 other berths, providing cabin accommodations for 53 passengers. She was fitted with lifeboat capacity for 231 and travelled in naval convoy. Under the recently revised regulations agreed to by the United States authorities, the joint United Kingdom and United States shipping board, the Admiralty, the Air Ministry and the Canadian authorities, a vessel of this description travelling in convoy is permitted to embark as crew and passengers a maximum of 75% of the lifeboat capacity. The lifeboat capacity as stated above was 231, 75% of which is 173. Personnel on board consisted of the crew of 86, and RCAF personnel numbering 53, a total of 139, well within the prescribed limits. Because of the superior type of available passenger accommodation, the speed of the ship and the provision of naval convoy, the offer of the entire available space to the RCAF was immediately accepted. Rumours to the effect that this was a slow freighter not suitable for passenger accommodation are, of course, not in accord with the facts. Every precaution was taken to safeguard the lives of these gallant young men. It should be pointed out that on account of the serious shipping shortage every available berth on such ships must be used, and had the space not been taken up by the RCAF officers of the other arms of the services would have been placed on Board. It should also be stated again that the submarine is still the enemy’s most powerful weapon and that the Battle of the Atlantic is not yet won. Any ocean trip today in any part of the world is fraught with danger and I think I may safely say that our record in transporting our soldiers and airmen to the United Kingdom is one of while we may all be proud. No one deplores more than I do the loss of 37 of the finest of our young men who gave their lives for their country as surely as if they had done so in actual combat with the enemy, and I extend my deepest sympathy to their loved ones in their bereavement.’ If further information becomes available, you are to be reassured it will be communicated to you at once. May I again extend to you my sincere sympathy in this time of great anxiety."

In mid-January 1944, Mr. Pidduck received a letter from the RCAF telling her that that George would now be presumed dead for official purposes. “It is most lamentable that a promising career should be thus terminated and I would like you to know that his loss is greatly deplored by all those with whom your son was serving.”

George had $3,500 in life insurance, his father the beneficiary.

In April 1945, Mr. Pidduck received a letter from Colonel L. M. Firth, Director of Estates. They received a cheque in the amount of $424.53, which included the balance of pay plus insured value of personal belongings lost at sea. “All of your son’s personal belongings were lost at sea as a result of enemy action. We realize that this will be a source of great disappointment to you and Mrs. Pidduck and are sincerely sorry that there are no effects available for return to you. The insured value of your son’s belongings amounted to $330.78.”

In October 1955, a letter addressed to George’s mother arrived from W/C W. R. Gunn informing her that George’s name would appear on the Ottawa Memorial, as George had no known grave, expressing sympathy on the loss of her gallant son.