January 1, 1905 - April 22, 1943

Ernest Mills MacDonald, born in Kentville, Nova Scotia, was the only child of Arthur John MacDonald, grocer, and Ella Jean (nee Mills) MacDonald. Mr. MacDonald died at the age of 65 from cancer. They attended the Church of England. Mrs. MacDonald later resided in Apple River, Nova Scotia with Mrs. Guy Elderkin. (Ernest noted on a form that his mother was having problems with her nerves.)

When he was seven, he fractured his left femur and then at 12, broke his nose.

His hobby was the wireless. “At our time, seriously interested in wireless telegraphy -- would be able to handle 20 words per minute with a little practice,” he wrote. He played skated and bowled extensively, played some tennis, with hockey, swimming, and baseball occasionally.

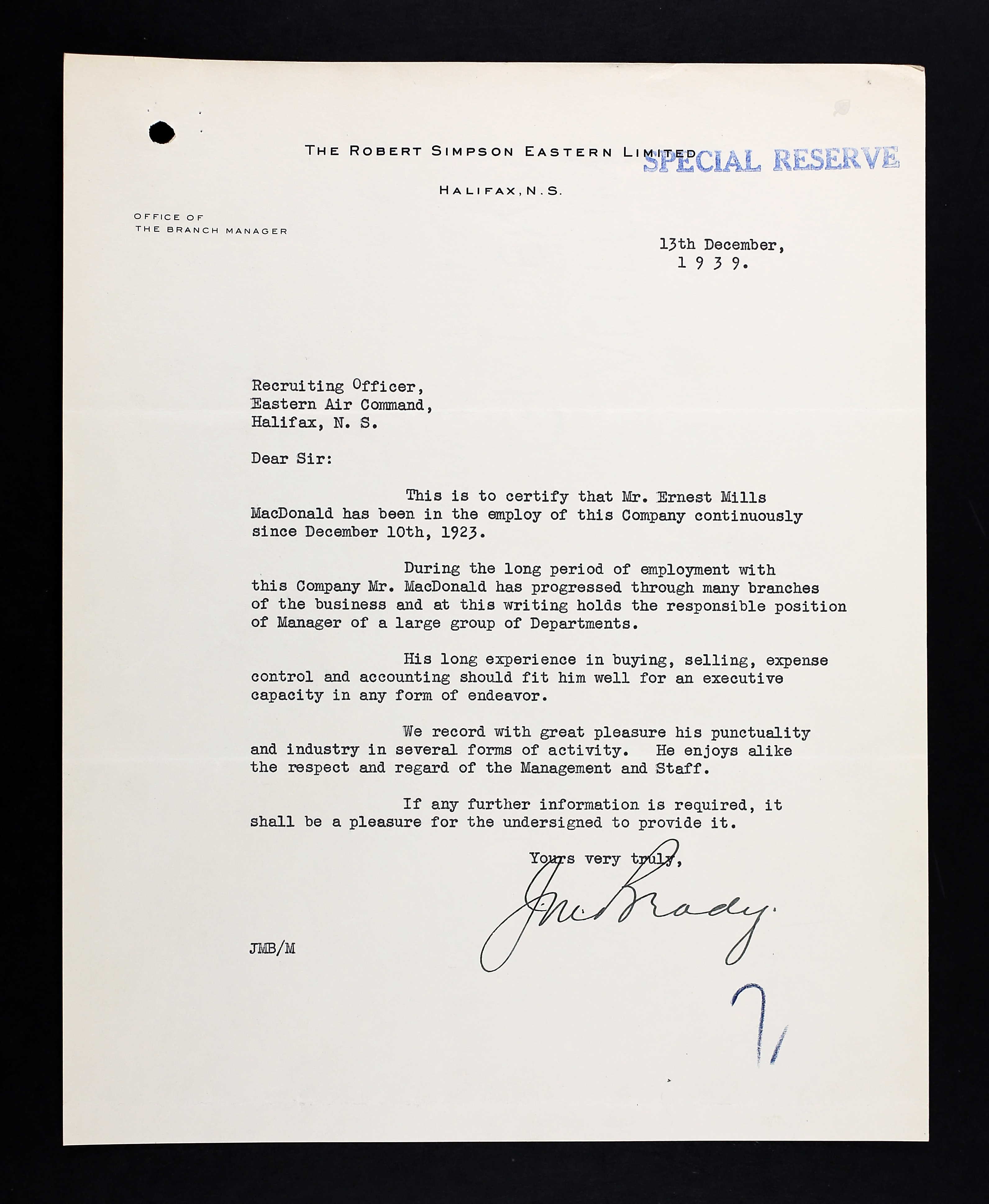

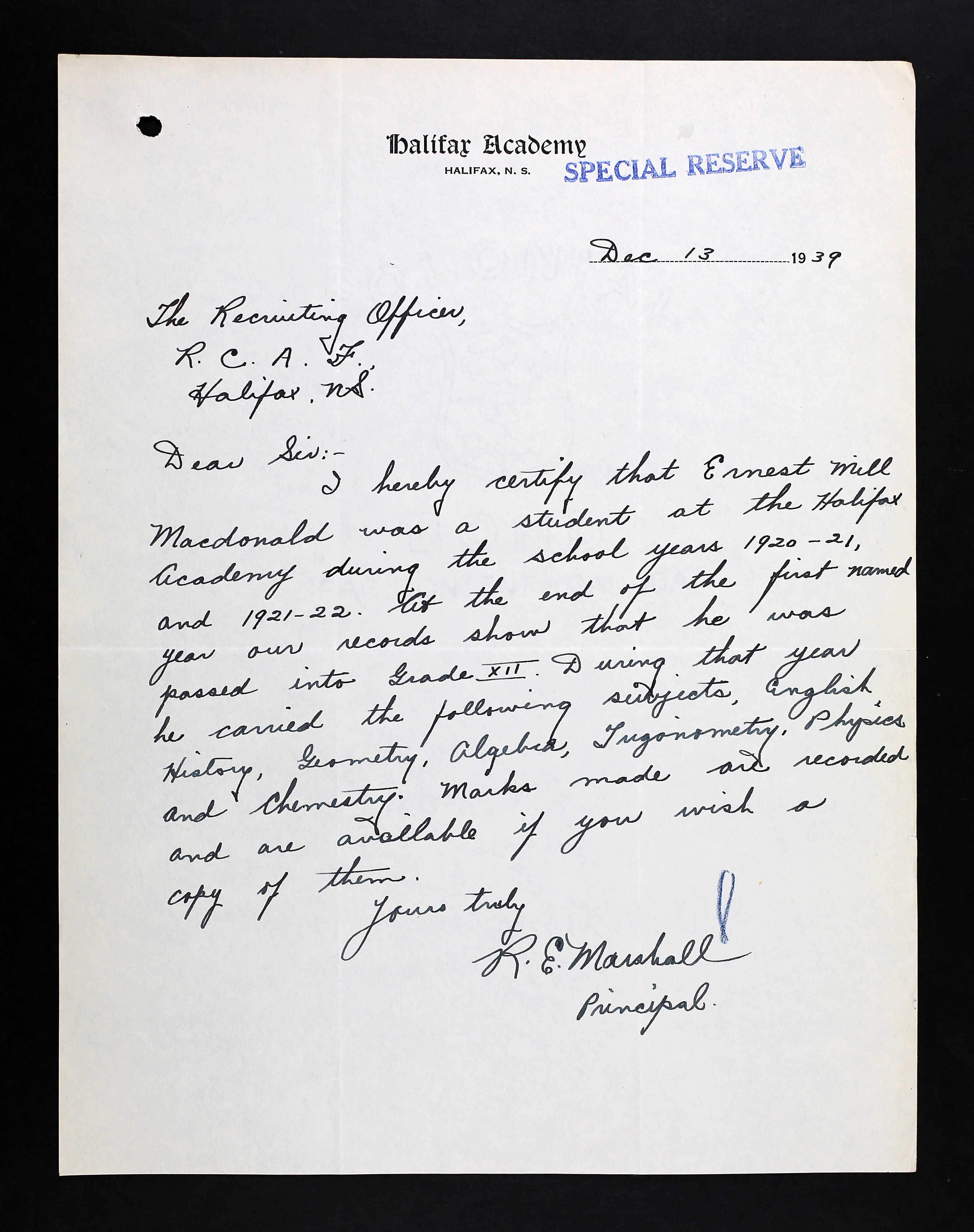

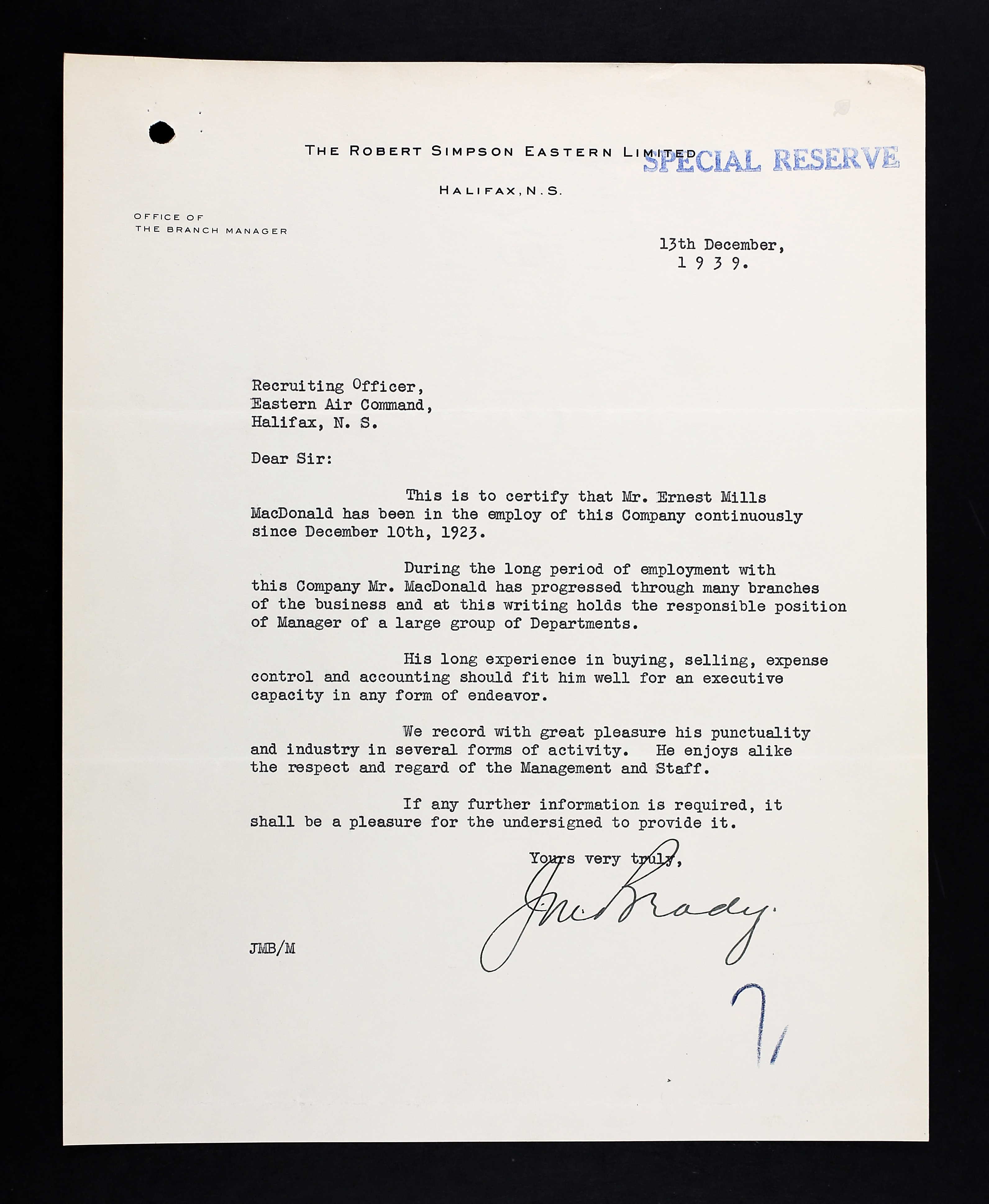

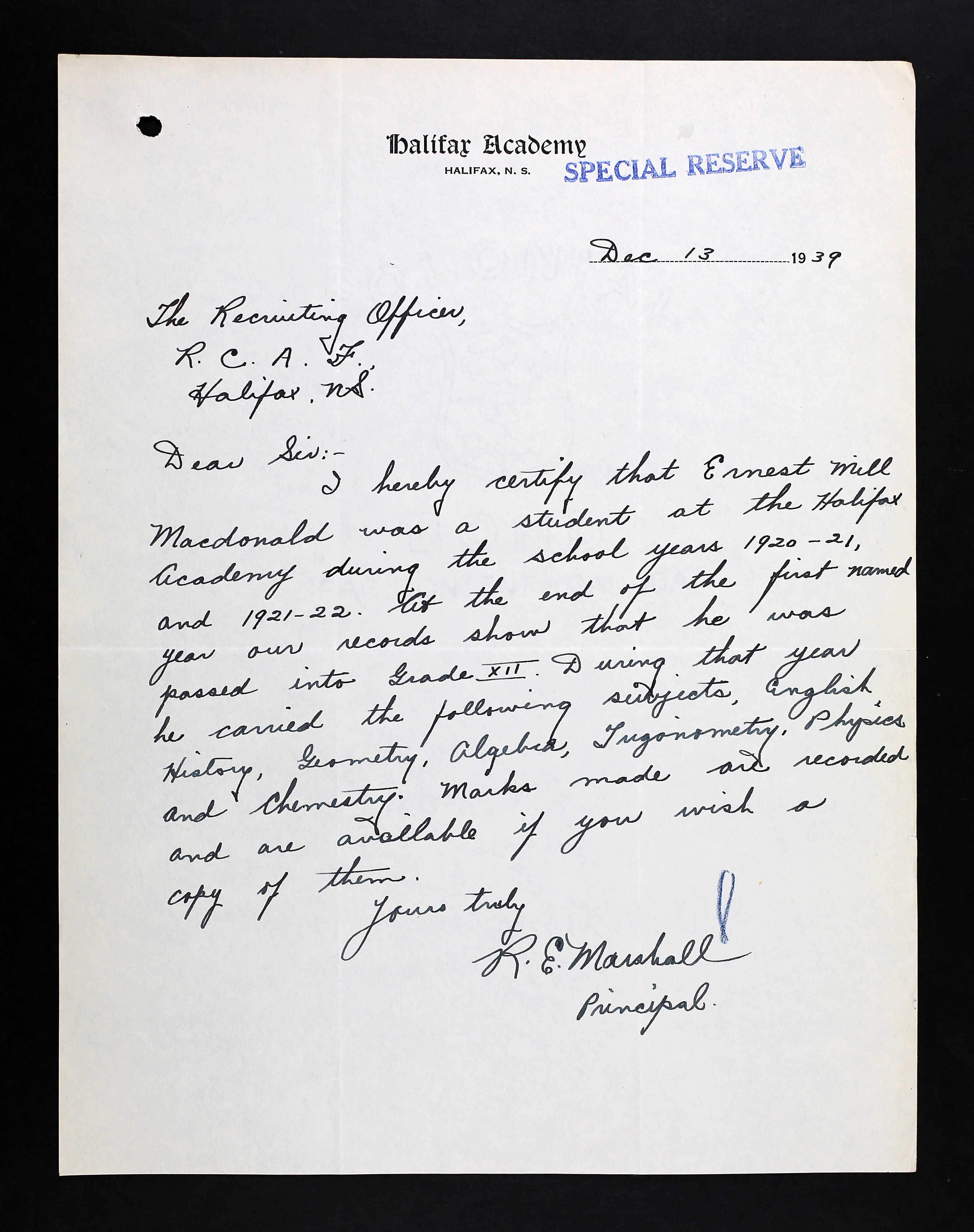

He had Grade XI, but did not write the examinations for Grade XII at Chester Aylesford Halifax Academy, graduating in 1922. Ernest was a store manager and merchandise buyer for Robert Simpson Eastern Ltd for 18 years (1922-1940) prior to enlistment with the RCAF in Halifax. He hoped to remain with the RCAF after the war.

On September 1, 1934, Ernest married Evelyn Durland Sollows in Halifax, Nova Scotia. She resided in Hamilton, then St. Catherines, Ontario. He took out two $5000 insurance policies with Evelyn as the beneficiary.

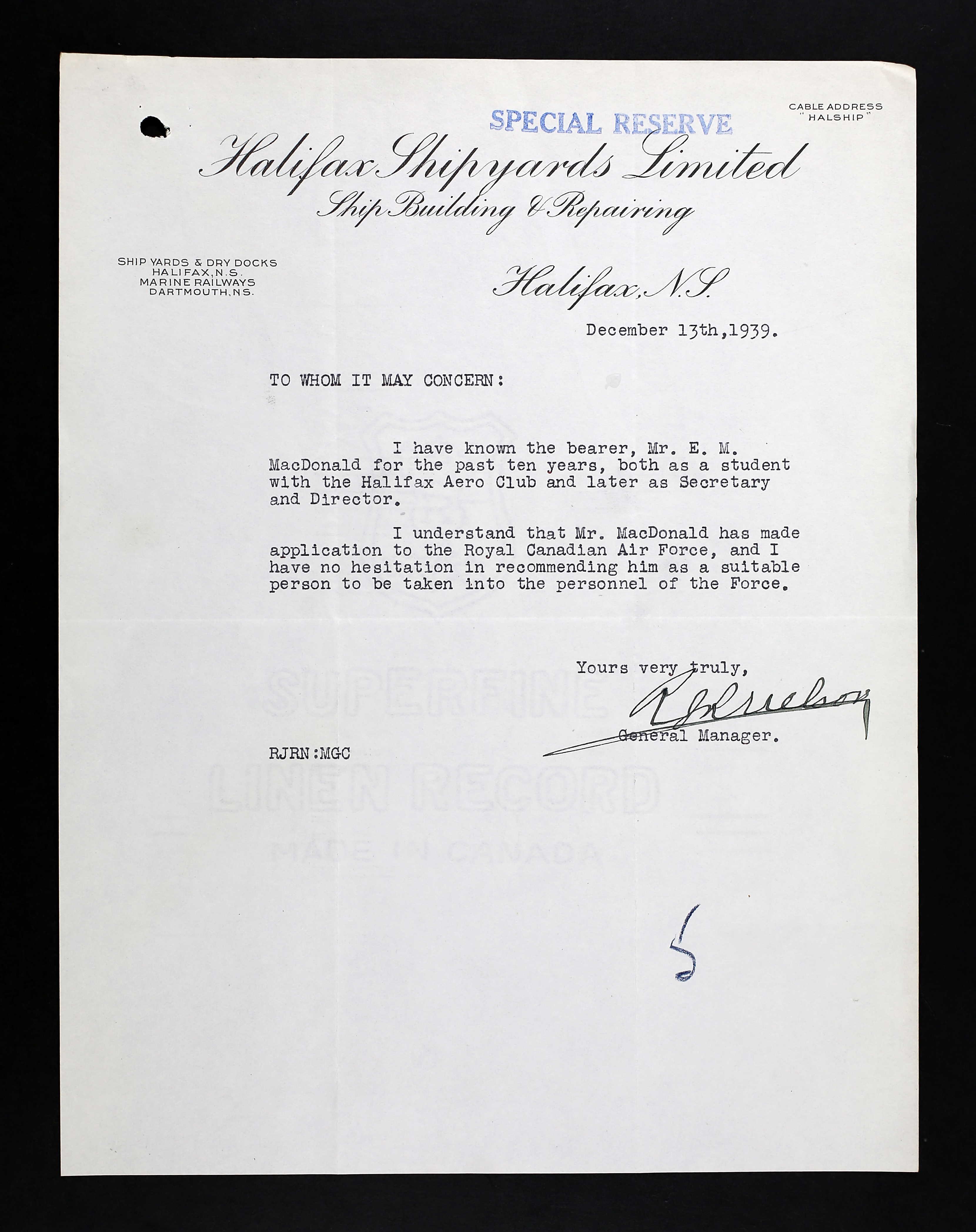

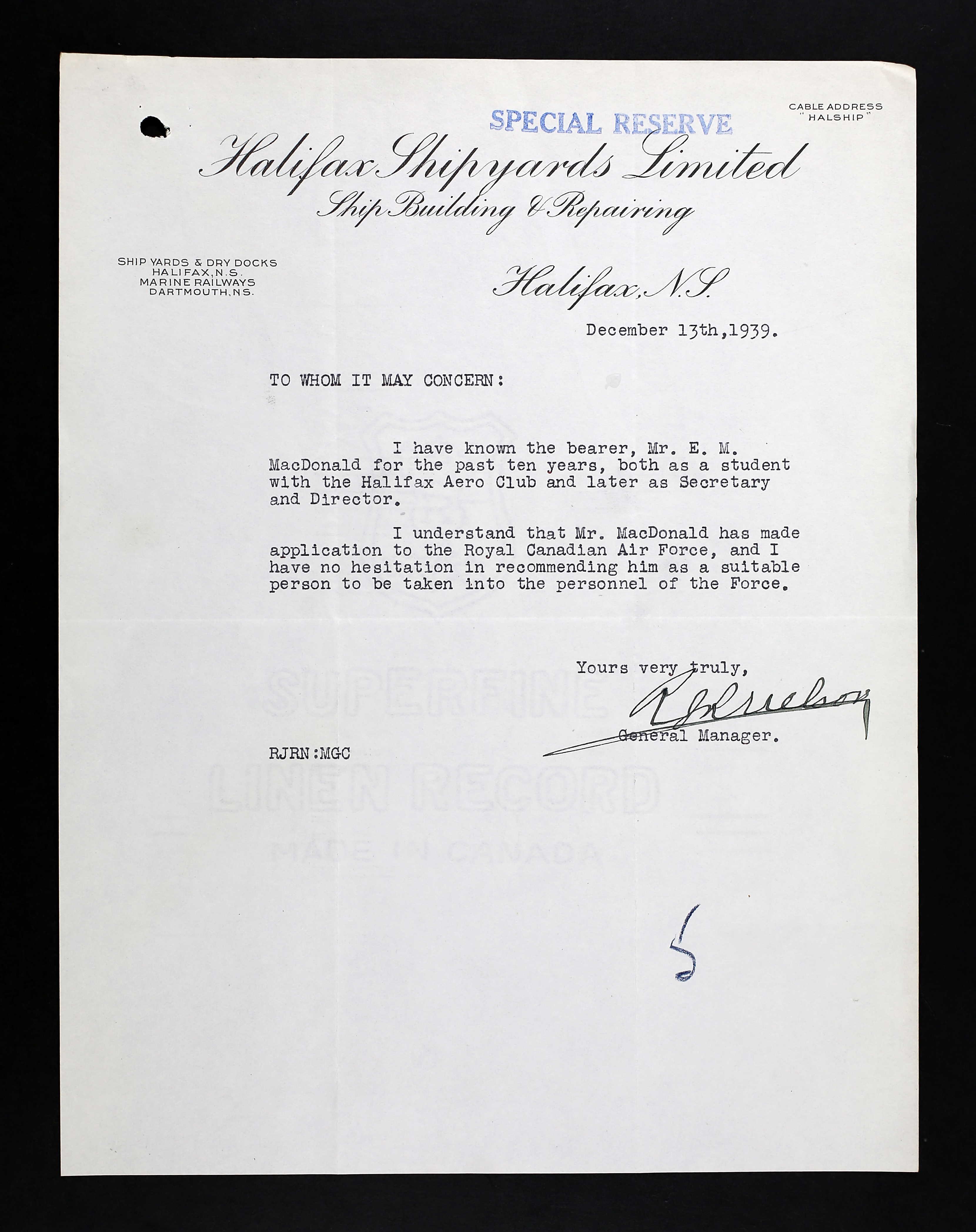

He first applied to the RCAF in November 1939, when he was 35 years old, wanting to be a pilot instructor, but and was informed he was too old to be a pilot in June 1940. He had 120 hours and 35 minutes flying solo and 14 hours, 25 minutes flying dual. As a passenger, he had 20 hours and 20 minutes in the air, all between 1932 and 1940.

On his general medical form, his physique was good as was his mentality; his teeth had good repair and his gums healthy, with an upper denture. He had blue eyes and brown hair with a fair complexion. The doctor noted he had a linear scar on his right breast and right thigh, plus a circular scar left forehead. He stood 5’ 6 ¼” tall, weighing 147 pounds. “Candidate co operates well in all tests. Seems a good type and very fit for his age.” (He was 34 or 35, depending upon which birth year. Evelyn indicated that Ernest was born in 1904, but other forms show 1905.)

“Candidate fit for full flying duties.” December 14, 1939. The interviewer, F/O N. J. Walsh noted that Ernest had flying experience, executive ability, and was the past director of the Halifax Aero Club, but was over flying age, at 34, but should still be considered as pilot due to his experience.

Ernest received a letter in April 1940 informing him that his application was in good standing, would be reviewed in competition with other candidates and then selections would be made to fill vacancies as they existed. The BCATP was still being developed and as establishment opened throughout Canada, appointments would be allocated geographically, so there were only a limited number in his area. There were more applicants than there were vacancies and he was asked to wait because in “all probability, the Air Force will require the services of the great majority of those who have applied.”

On July 20, 1940, Ernest was accepted into the RCAF. “Type: very good. General appearance: very good. Suitability: Instructor’s Course.” More evaluations: “Well recommended. Good character. Well dressed. Above average. Very good applicant for instructor’s course. Keen to fly. Very good pilot. Strongly recommended.”

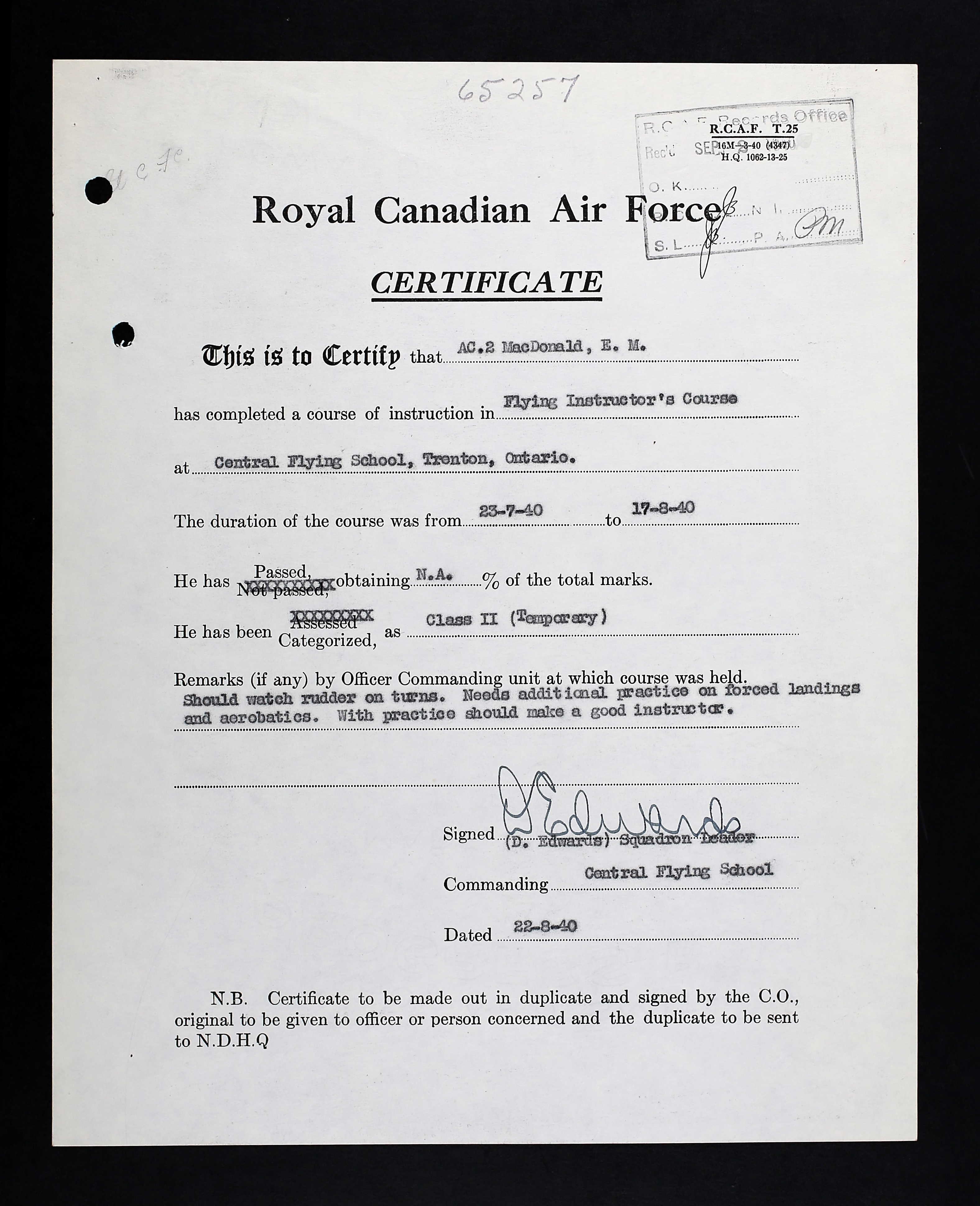

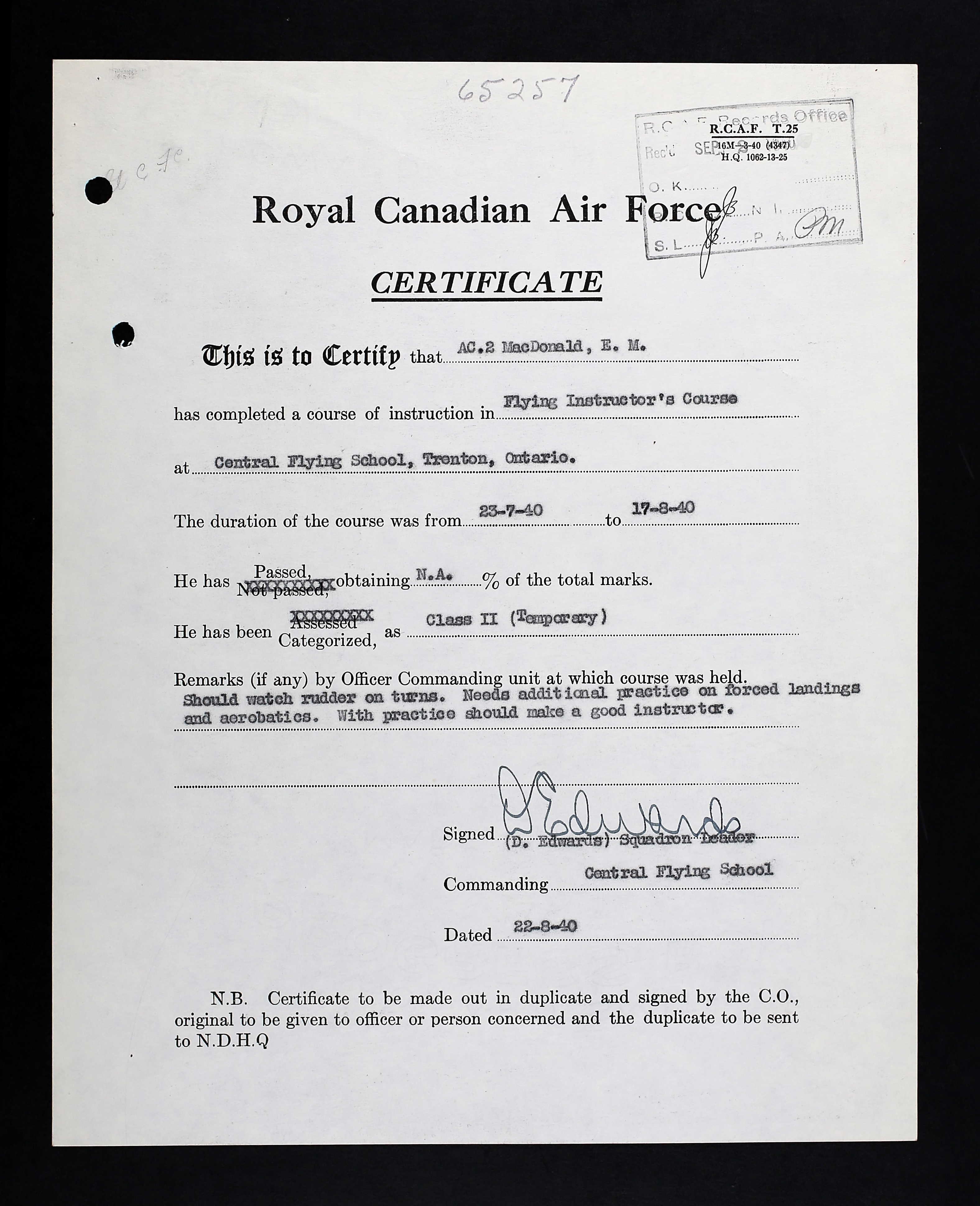

July 23, to August 17, 1940, Ernest was in Trenton, Ontario. “Knowledge of sequence good. Will make a very good instructor with experience. Has made great improvement in flying on this course. Aerobatics average. Instrument flying average. Ability to impart knowledge: average. Ability as a pilot: average. Remarks: should watch rudder on turns. Needs additional practice on forced landings and aerobatics. With practice, he should make a good instructor.”

It is unknown what he did between August 1940 and September 1942. There was some indication that he was on leave without pay on September 2, 1940. It does not appear that he was an instructor, but that he went into training to become a pilot for the RCAF and then was preparing to be sent overseas.

On September 13, 1942, he was taken on strength at No. 9 EFTS, St. Catherines, Ontario, but then immediately was sent to No. 5 Manning Depot, Lachine, Quebec until October 10 of that year. Evelyn remained in St. Catherines.

From October 11, 1942 to December 31, 1942, Ernest was at No. 6 SFTS, Dunnville, Course C5. He was fourth in class, but how any students were in the class is unknown. He earned 81.3% “This pupil pilot has passed all tests required for Pilot’s Flying Badge. Keen and capable, above average in all respects. An outstanding student.” Ernest was recommended for commission. He earned his Pilot’s Flying Badge on December 30, 1942.

Ernest was sent to No 1 GRS, Summerside, PEI January 23, 1943 until April 10, 1943.

On April 4, 1943, he was in Halifax, Nova Scotia at Y Depot, then associated with RAF Trainees’ Pool by April 13, 1943, awaiting a ship to take him and others overseas.

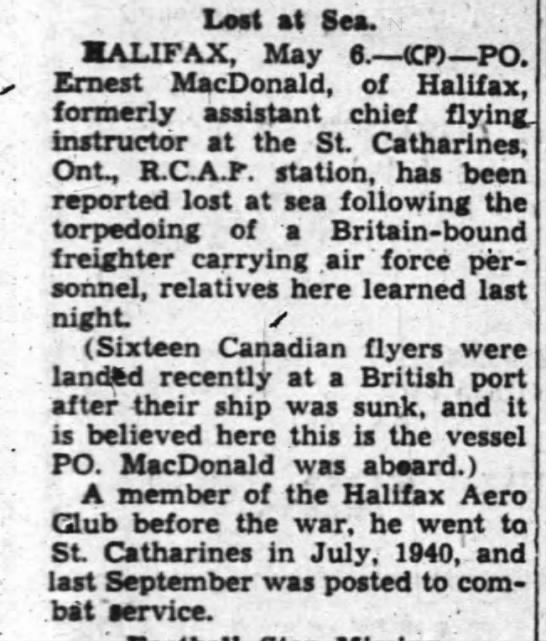

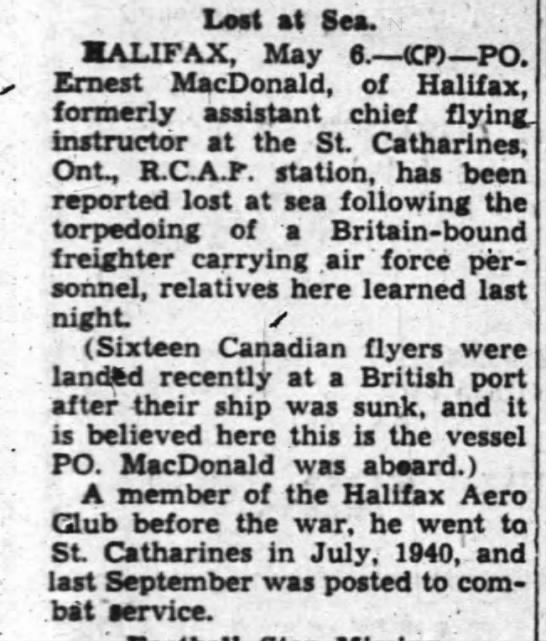

On April 22, 1943, Ernest MacDonald was aboard the Amerika, British Motor merchant ship. It was on its way from Halifax, Nova Scotia to Liverpool. It was torpedoed as the ship was heading to Britain. It was a straggler in convoy HX-234. Thirty-seven men, all officers in the RCAF, were presumed missing as a result of enemy action at sea; sixteen were landed at a British port after their ship was sunk by U-306, south of Cape Farewell, off Greenland. Forty-two crew members and seven gunners were also amongst those who were lost. The master, Christian Nielsen, 29 crewmembers, eight gunners, and sixteen passengers were picked up by the HMS Asphodel, and landed at Greenock. General cargo, including metal, flour, meat and 200 bags of mail were also lost.

Evelyn received a letter dated June 25, 1943 from F/L W. R. Gunn, RCAF Casualties Officer for Chief of the Air Staff. "Since my letter of May 6th, no additional news has been received. Attached is a list of the names and next-of-kin of sixteen Royal Canadian Air Force officers who embarked on the same ship as your son and following enemy action at sea were safely landed in the United Kingdom. The following official statement was made in the House of Commons....’I have been in receipt of communications from a number of members of this house and from people outside with reference to rumours regarding the recent loss of a number of members of the RCAF by the sinking of a ship in the north Atlantic and I desire to make the following statement on the facts. The vessel in question was a ship of British registry of 8,862 tons, designed for peace-time carriage of both passengers and freight, and having a speed of fifteen knots. She carried a crew of 86 and the passenger accommodation consisted of 12 two-berth rooms with bath and 29 other berths, providing cabin accommodations for 53 passengers. She was fitted with lifeboat capacity for 231 and travelled in naval convoy. Under the recently revised regulations agreed to by the United States authorities, the joint United Kingdom and United States shipping board, the Admiralty, the Air Ministry and the Canadian authorities, a vessel of this description travelling in convoy is permitted to embark as crew and passengers a maximum of 75% of the lifeboat capacity. The lifeboat capacity as stated above was 231, 75% of which is 173. Personnel on board consisted of the crew of 86, and RCAF personnel numbering 53, a total of 139, well within the prescribed limits. Because of the superior type of available passenger accommodation, the speed of the ship and the provision of naval convoy, the offer of the entire available space to the RCAF was immediately accepted. Rumours to the effect that this was a slow freighter not suitable for passenger accommodation are, of course, not in accord with the facts. Every precaution was taken to safeguard the lives of these gallant young men. It should be pointed out that on account of the serious shipping shortage every available berth on such ships must be used, and had the space not been taken up by the RCAF officers of the other arms of the services would have been placed on Board. It should also be stated again that the submarine is still the enemy’s most powerful weapon and that the Battle of the Atlantic is not yet won. Any ocean trip today in any part of the world is fraught with danger and I think I may safely say that our record in transporting our soldiers and airmen to the United Kingdom is one of while we may all be proud. No one deplores more than I do the loss of 37 of the finest of our young men who gave their lives for their country as surely as if they had done so in actual combat with the enemy, and I extend my deepest sympathy to their loved ones in their bereavement.’ If further information becomes available, you are to be reassured it will be communicated to you at once. May I again extend to you my sincere sympathy in this time of great anxiety."

After the sinking of the Amerika, the Canadian Pension Commission was concerned that there might be liability against the British Ministry under the Air Training Agreement and it was considered advisable to have British application forms completed should an application be filed by the parents of those who were lost aboard the Amerika.

On January 12, 1944, Air Marshall Robert Leckie wrote to Evelyn to inform her that Ernest was, for official purposes, presumed to have died on Active Service on April 22, 1943.

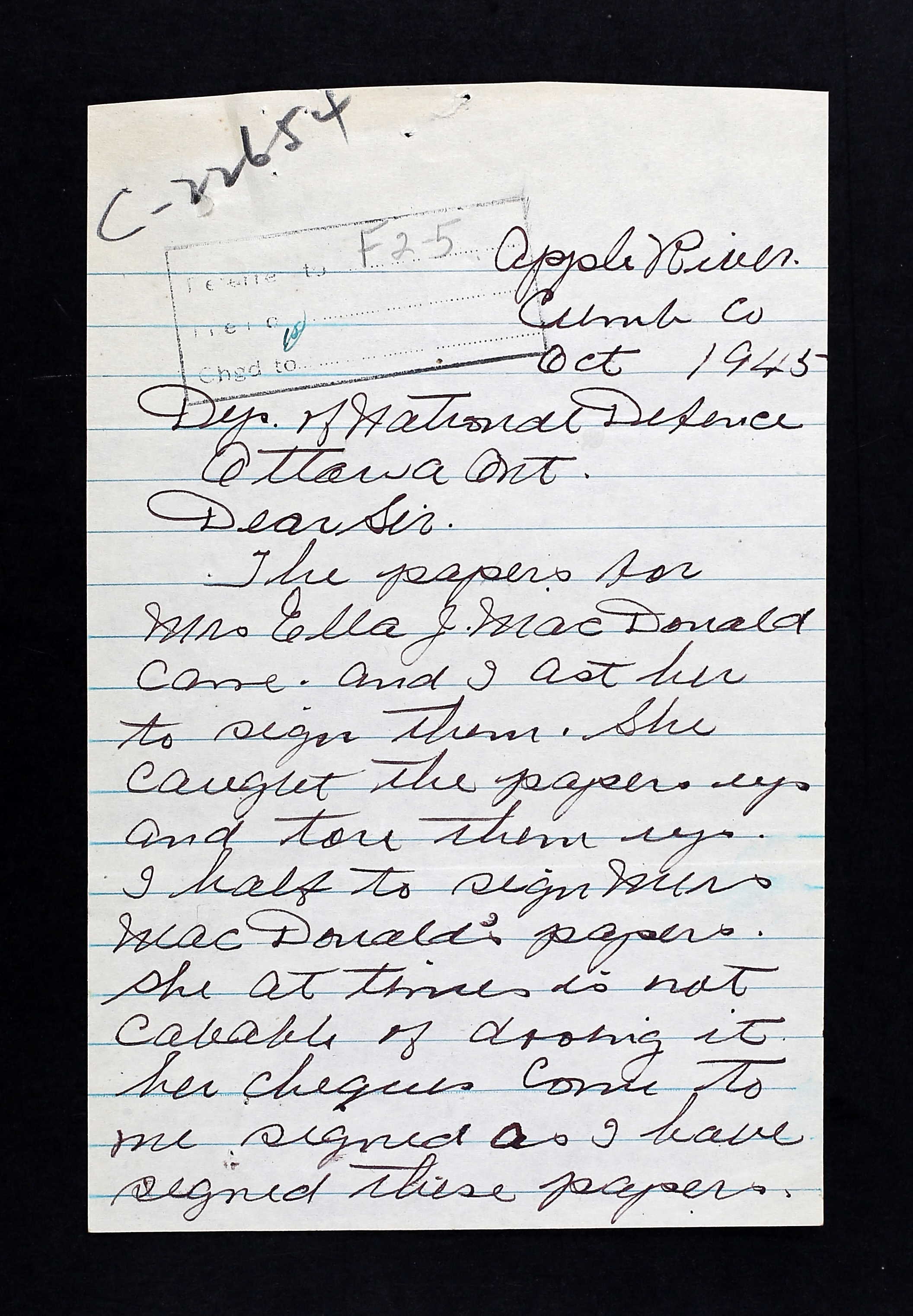

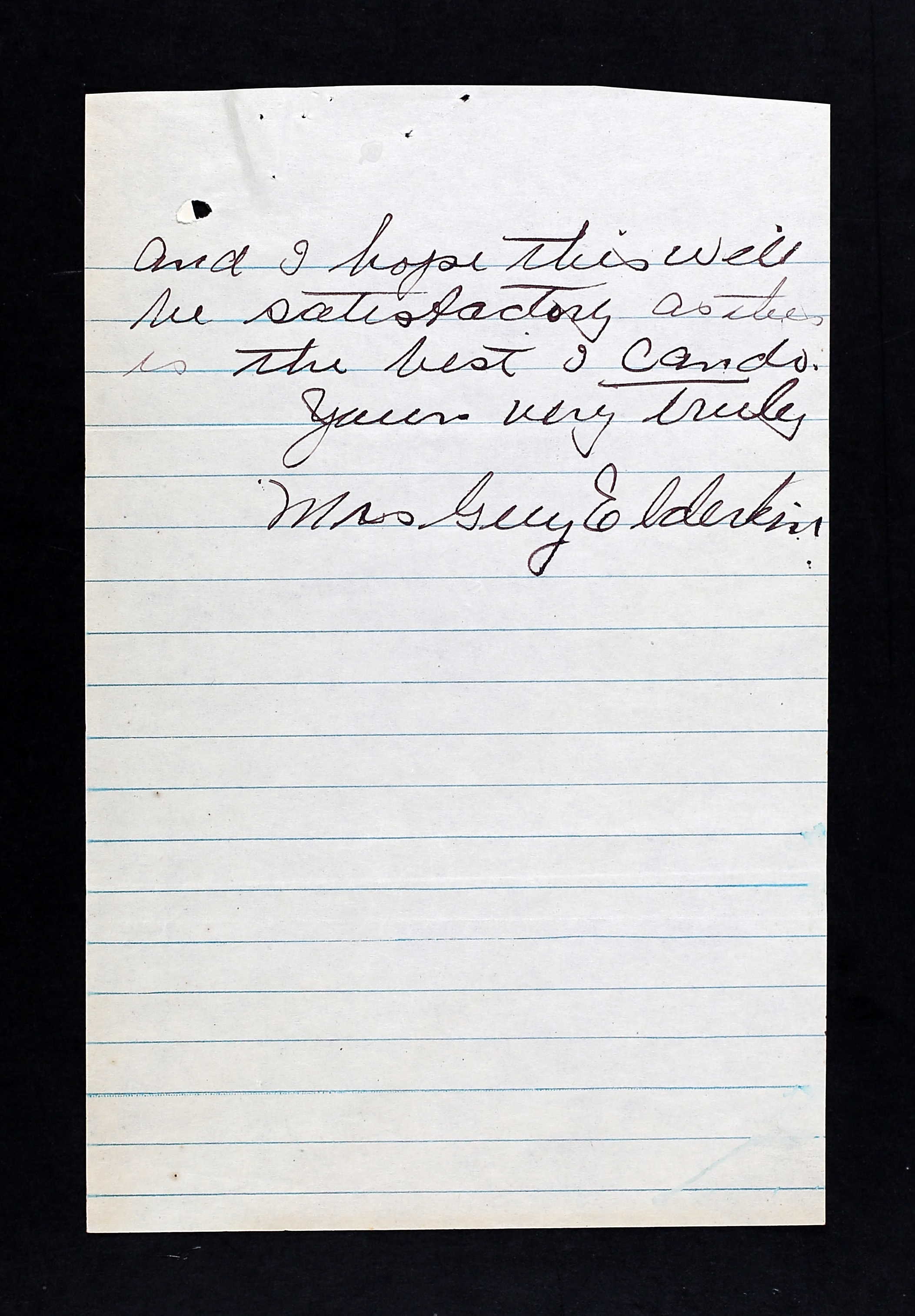

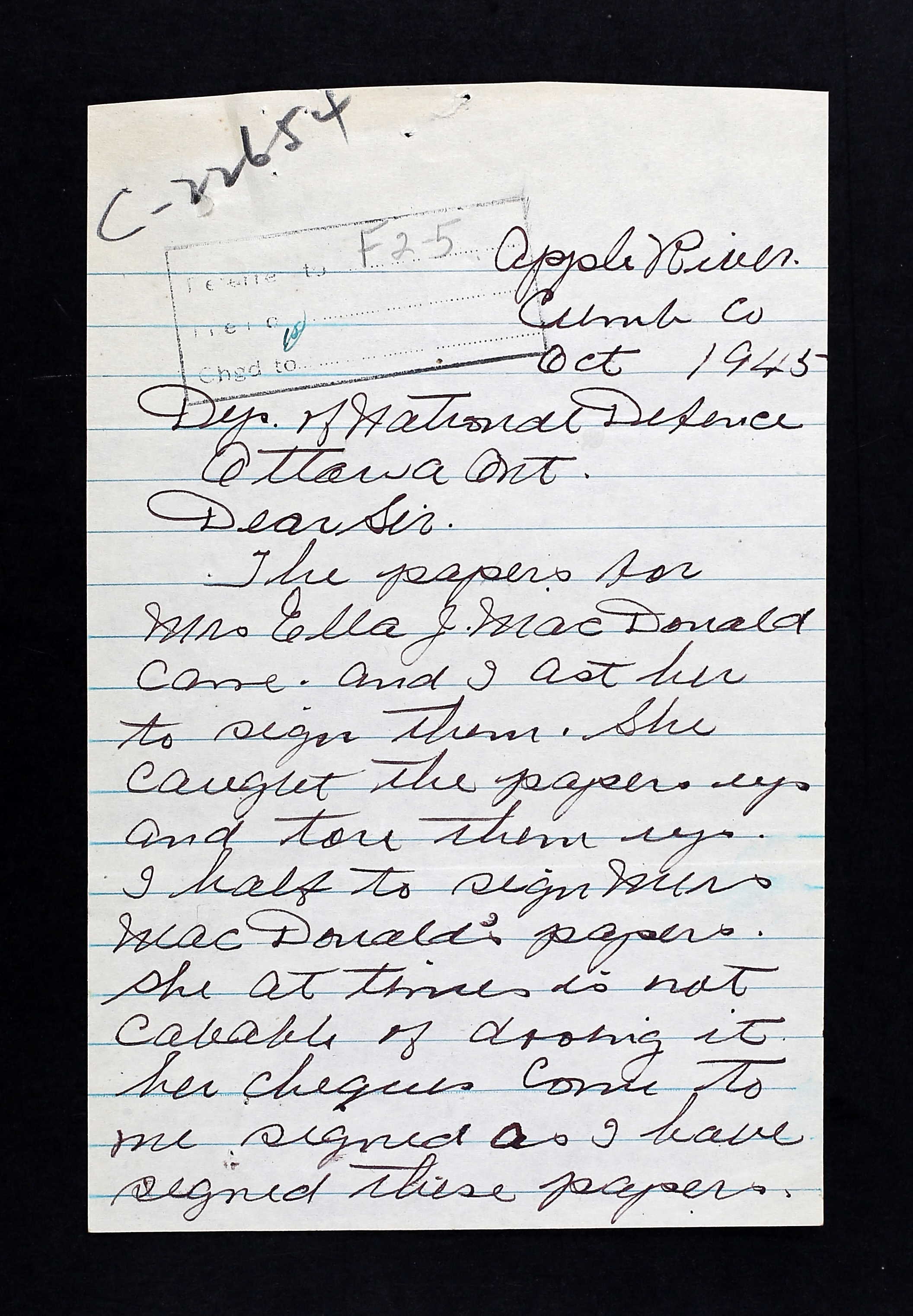

Ernest’s mother was living in Apple River, Nova Scotia. A letter dated October 1945, written by Mrs. Guy Elderkin, with whom she had been residing wrote: "The papers for Mrs. Ella MacDonald came and I ast (sic) her to sign them. She caught the paper up and tore them up. I half (sic) to sign Mrs. MacDonald’s papers. She at the moment is not capable of doing it. Her cheques come to me signed as I have signed these papers and I hope this will be satisfactory as this is the best I can do."

In October 1955, a letter from W/C Gunn to Evelyn noting a Washington, DC, address informed her that Ernest’s name would appear on the Ottawa Memorial. The letter was returned. A note on the letter: “Returned in mails. Send form to mother.”