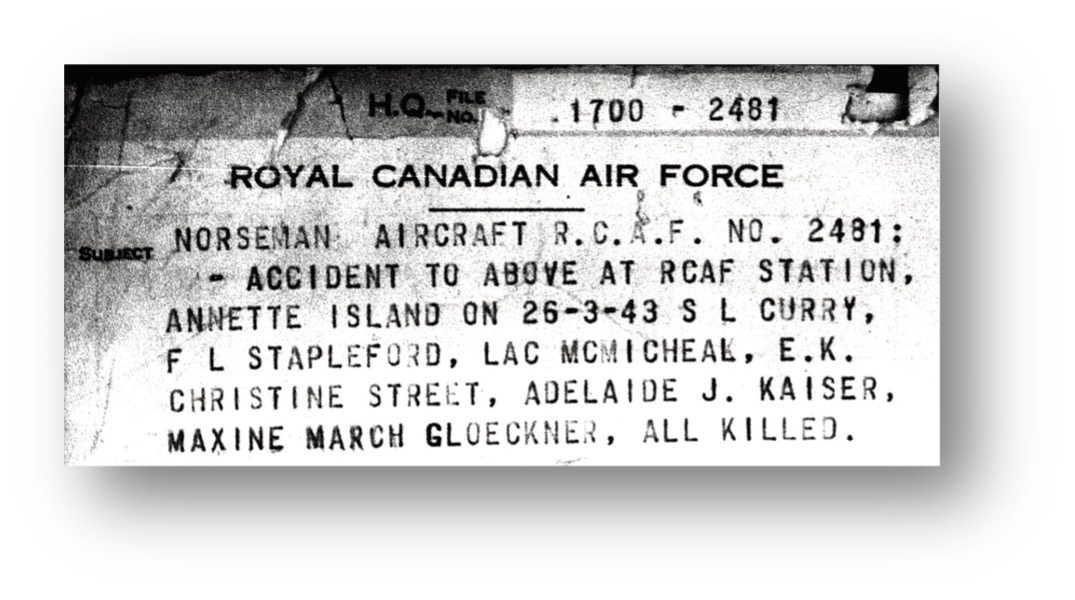

October 3, 1915 - March 26, 1943

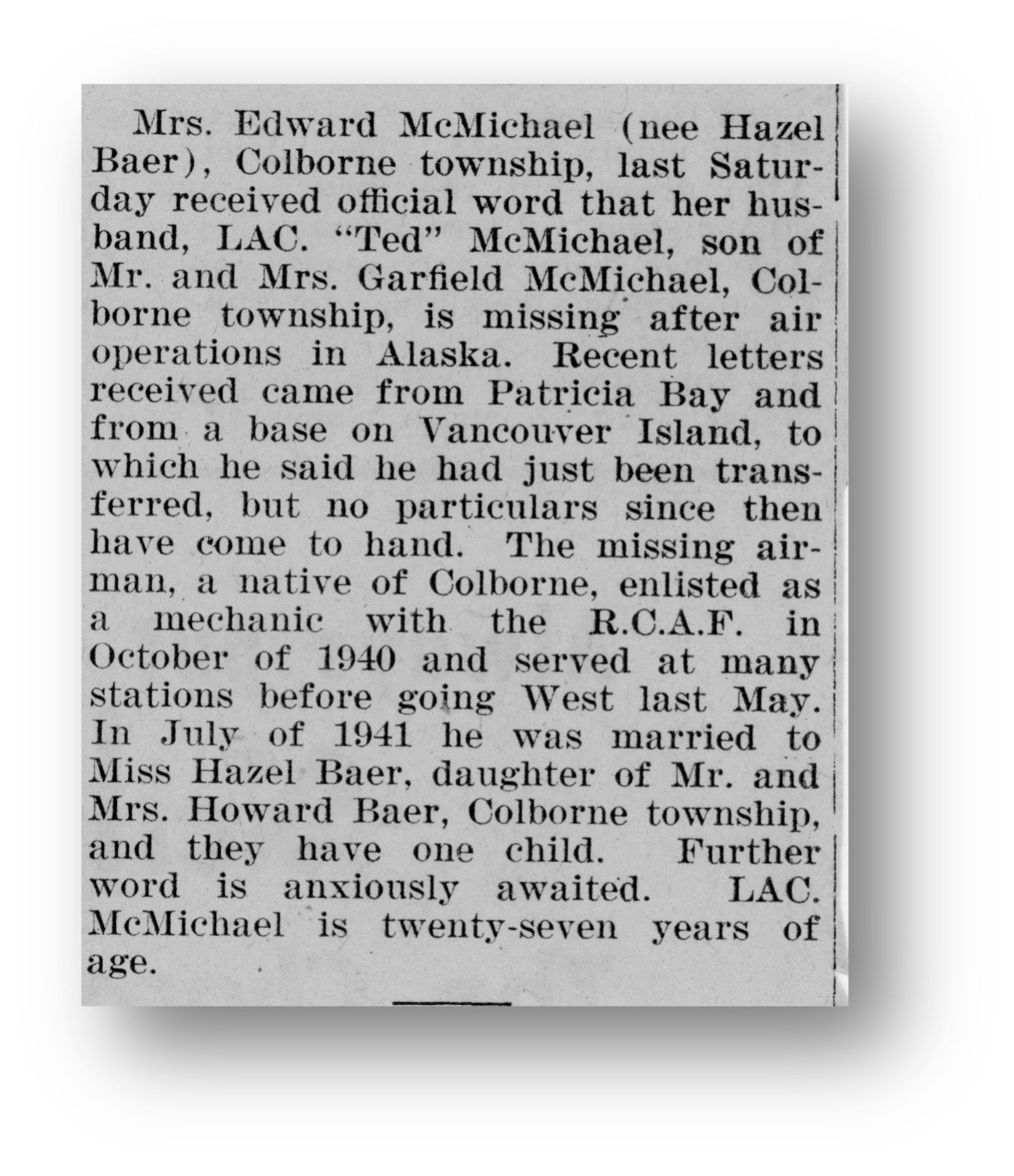

Edward ‘Ted’ Kitchener McMichael was born on October 3, 1915, in Hullet Township, Ontario, about one and a half hours north of London, Ontario. He was the son of Garfield and Louise McMichael, and brother to Reginald, Isabelle, Harvey, Franklin, Ruby and Arthur.

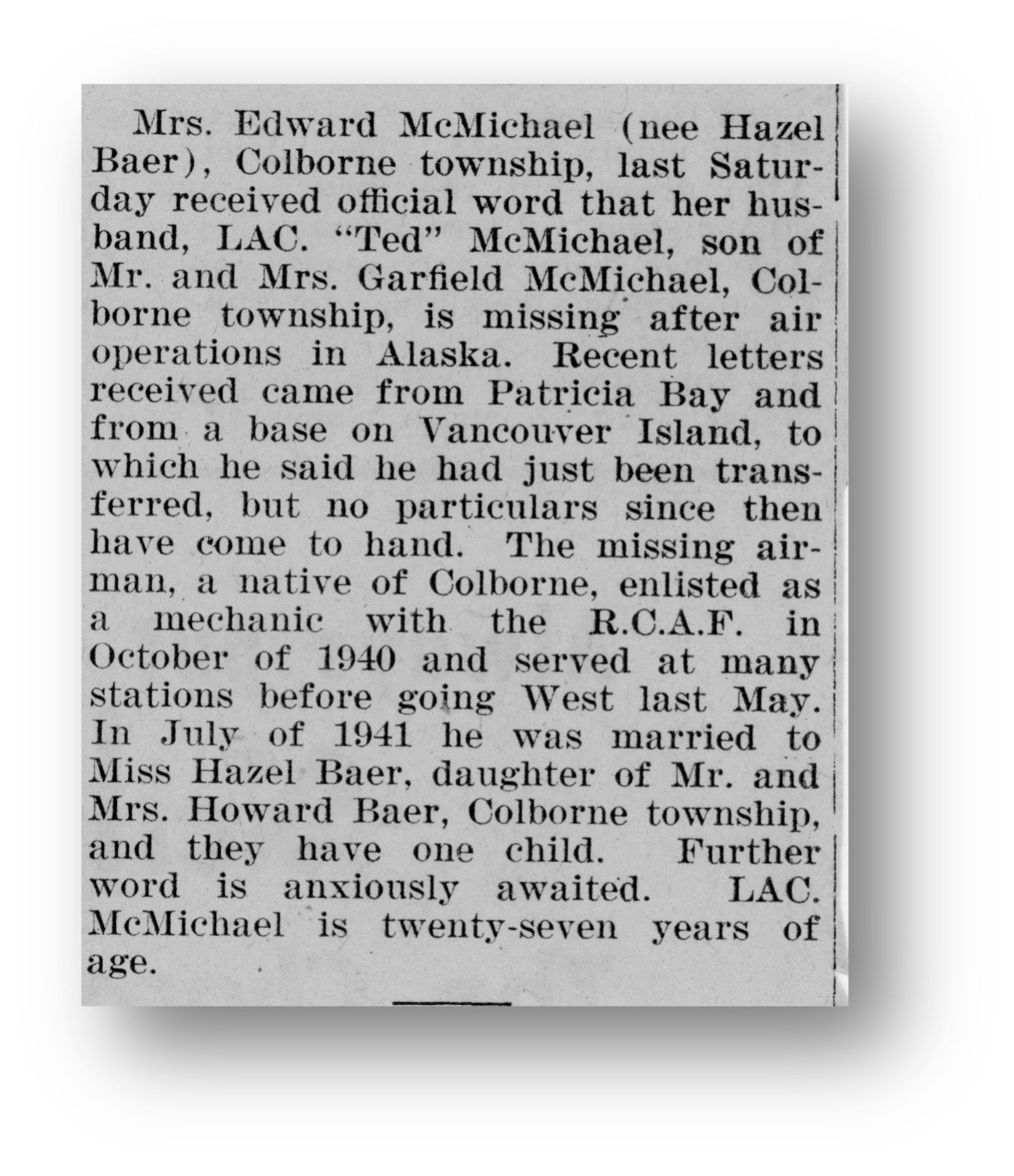

Ted enjoyed playing softball and hockey and he liked to hunt. He was a machine mechanic, a charger at George Mulholland Foundry in Sarnia Ontario before he enlisted with the Royal Canadian Air Force in London, Ontario in July 1940. At that time, he was 25 years old, stood 5’9” tall and weighed 158 pounds. He had light brown hair, hazel eyes, and a fair complexion. Ted indicated he would like to become a farm implement salesman after the war.

Ted married Hazel Adelia Baer, of Goderich, Ontario, a teacher, and together they had their son, Gerald (Gerry) Edward. Ted was able to meet his son during a furlough in February 1943.

He trained to become an aero engine mechanic, travelling from London, Ontario to Brandon, Manitoba, then to Toronto and onwards to St. Thomas. By May 1941, he was at Mossbank, Saskatchewan. In March 1942, he was posted to Patricia Bay, British Columbia. Many family photos show him enjoying the sights of Victoria. Hazel visited her husband while he was stationed there, taking up an apartment with two friends whose husbands were also at Pat Bay. When Ted was posted to Alaska, Hazel returned home to Goderich, Ontario.

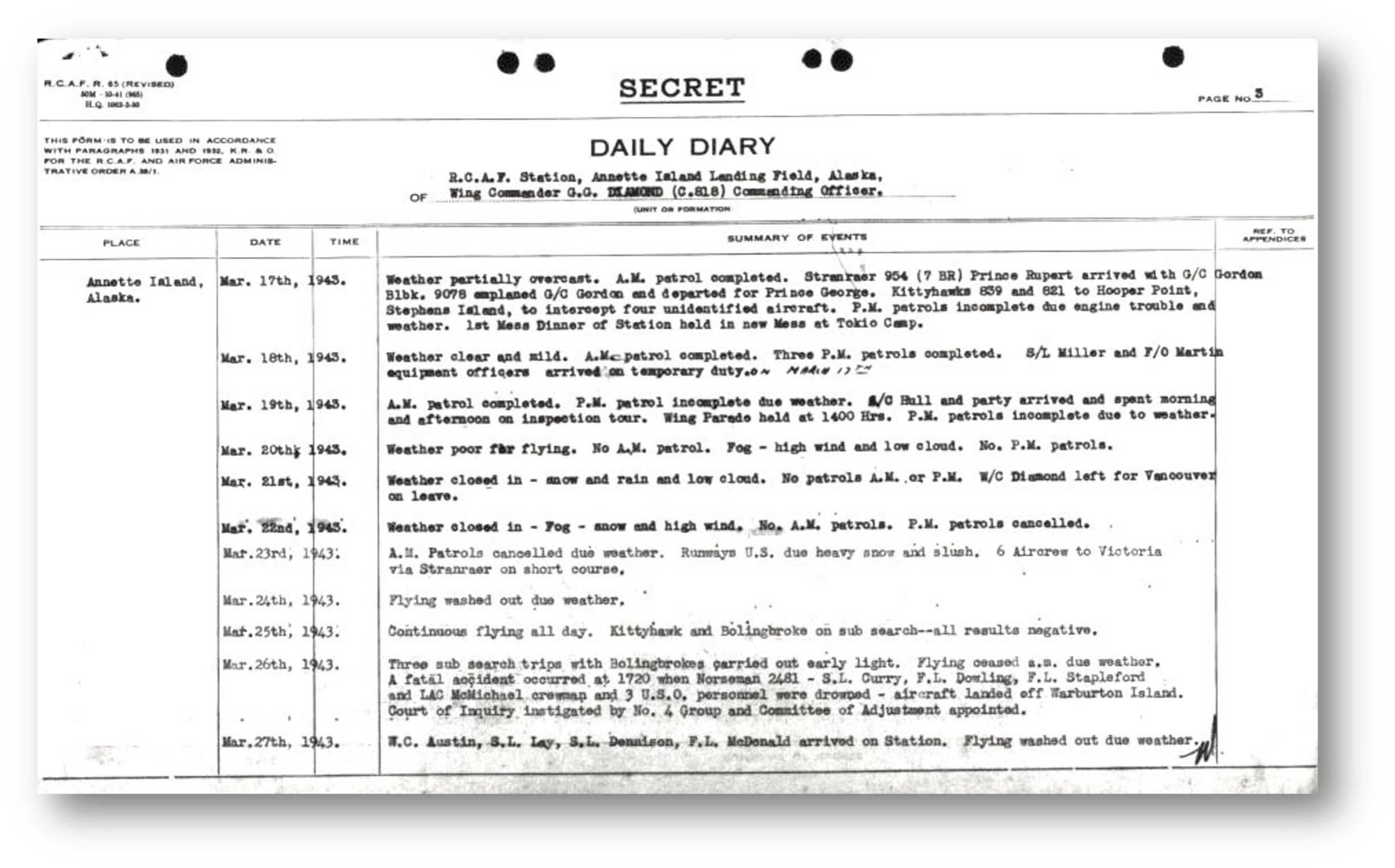

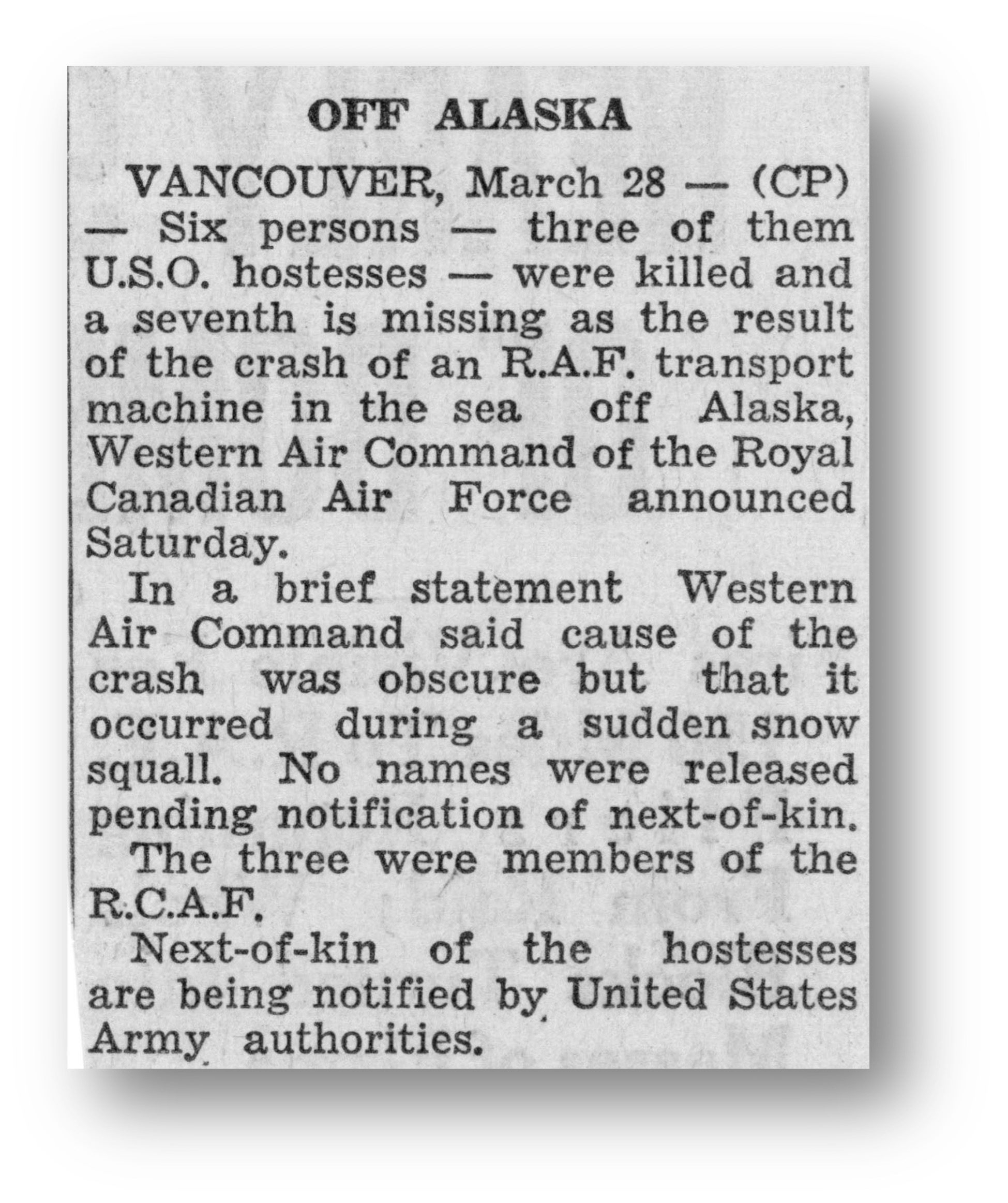

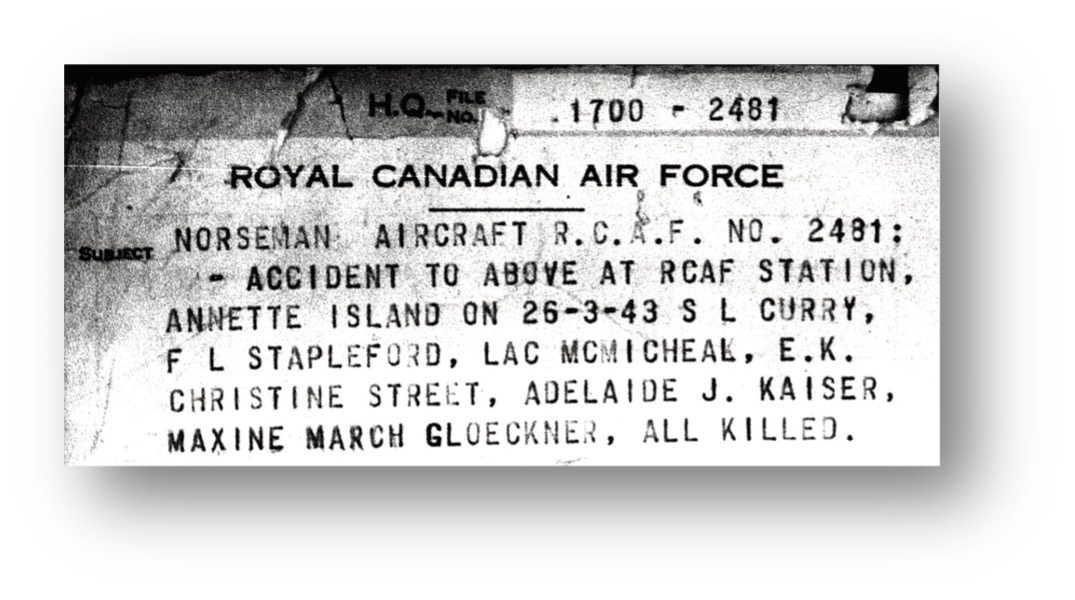

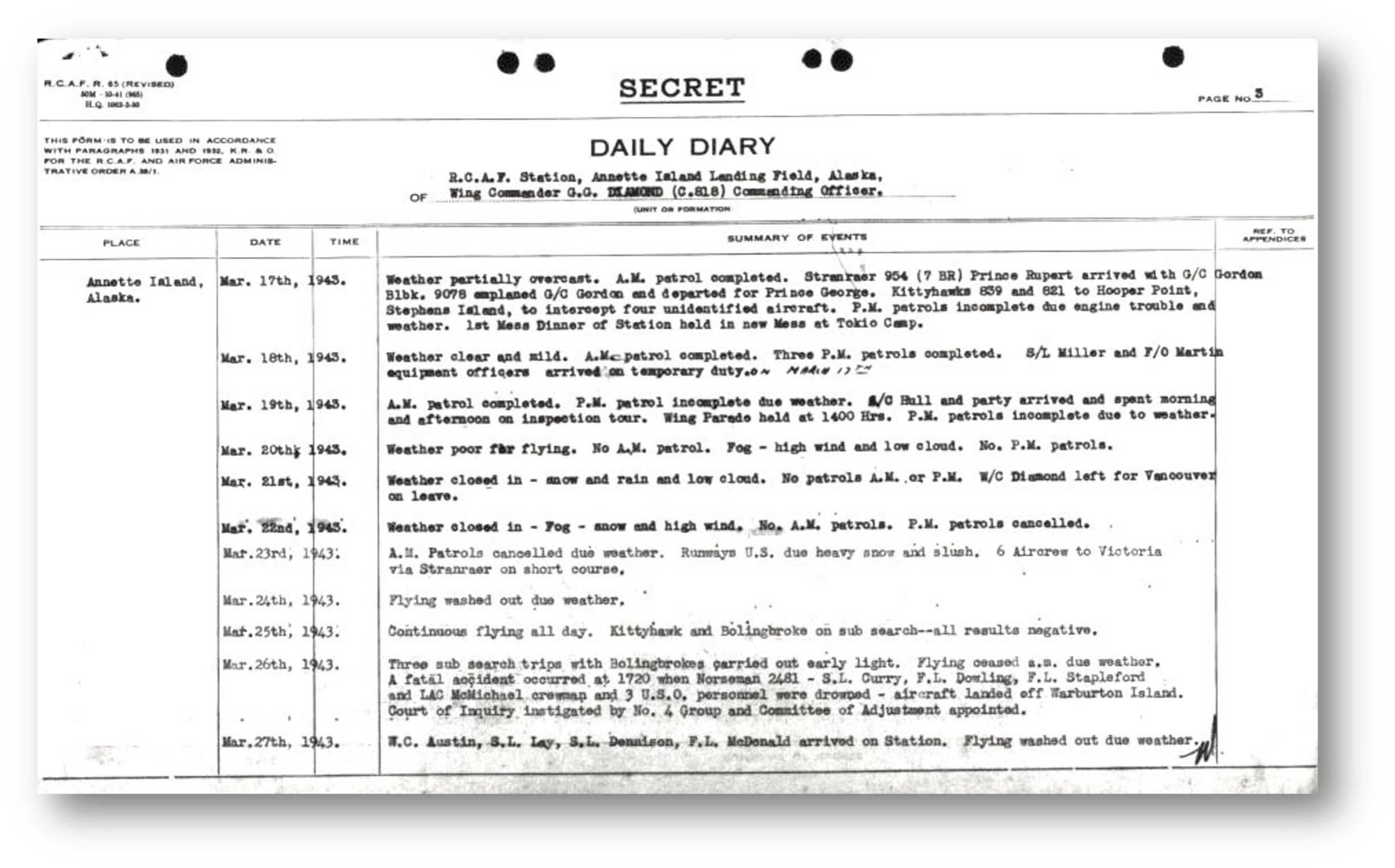

S/L Fred Burpee Curry was the pilot of Norseman #2481, #115 Bomber Reconnaissance Squadron based at Annette Island, Alaska. Aboard the flight were six passengers, three with the Royal Canadian Air Force: F/L E. B. Stapleford, F/L I.M. Dowling, and LAC E. K. McMichael, and three American civilians, part of the USO: Miss M. Gloeckner, Miss A.J. Kaiser, and Miss C. Street.

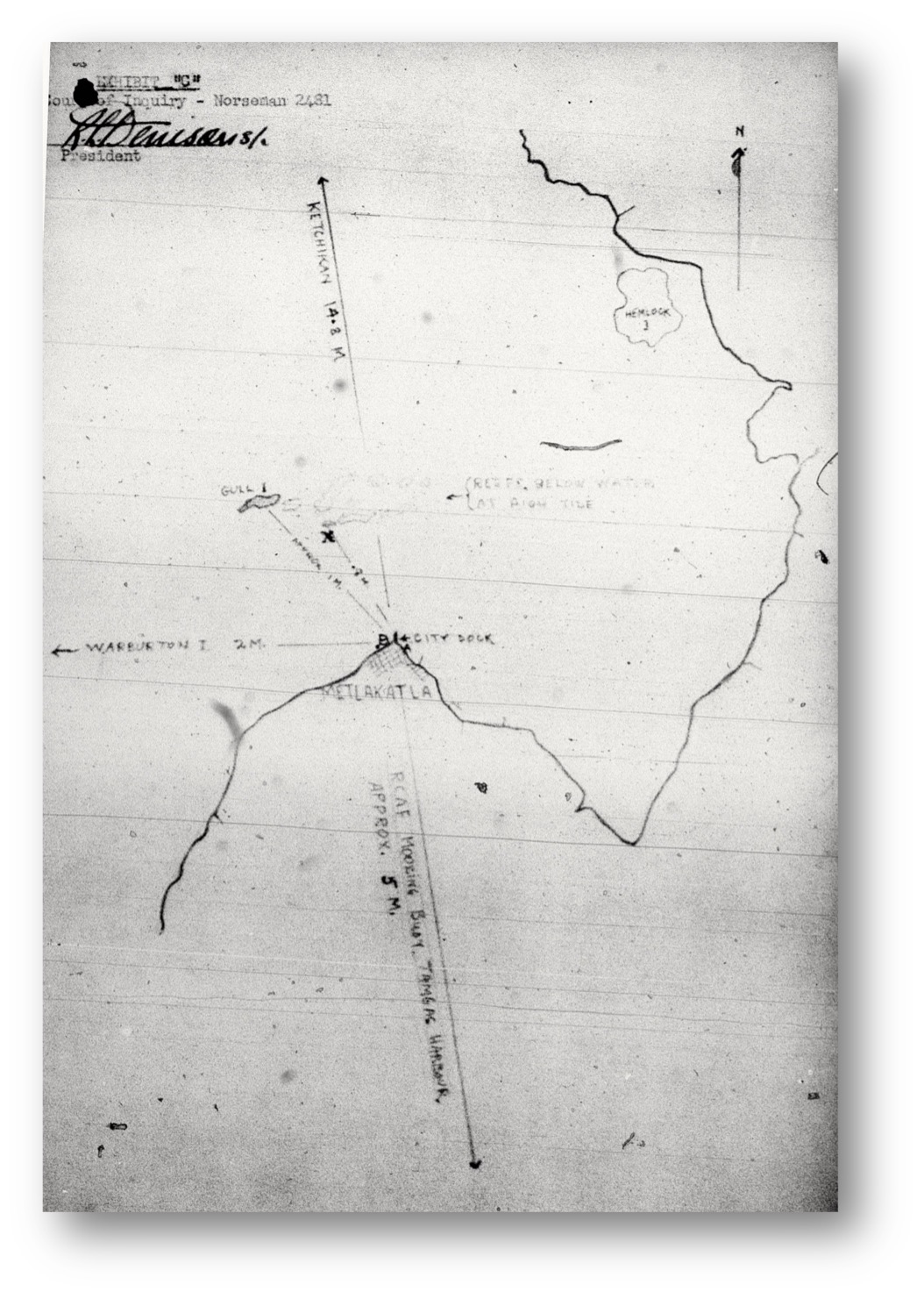

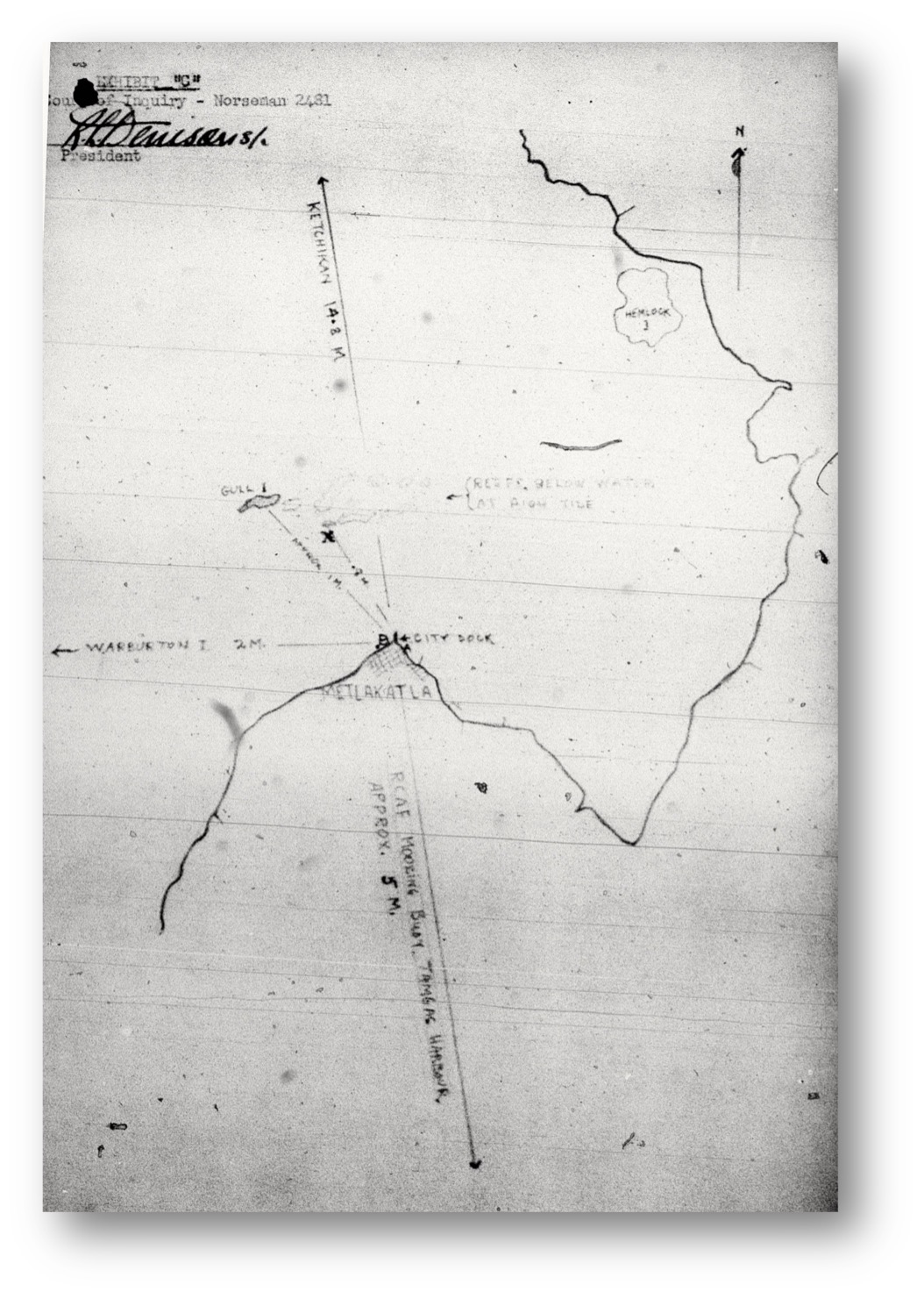

The Court of Inquiry for Norseman 2481 sat in Metlakatla, Alaska from Friday April 2, 1943. Assemblies and adjournments were also held at Annette Island and Ketchikan in the first few days of the inquiry. The following is a synopsis from the witness statements.

Squadron Leader Curry, with 108 hours on the Norseman was an experienced pilot. He had flown a variety of aircraft, with him logging in the most hours on the Bolingbroke (646 hours 40 minutes). It was supposed to be a routine return transportation flight from Annette Island, Alaska to Ketchikan, twenty minutes away by air.

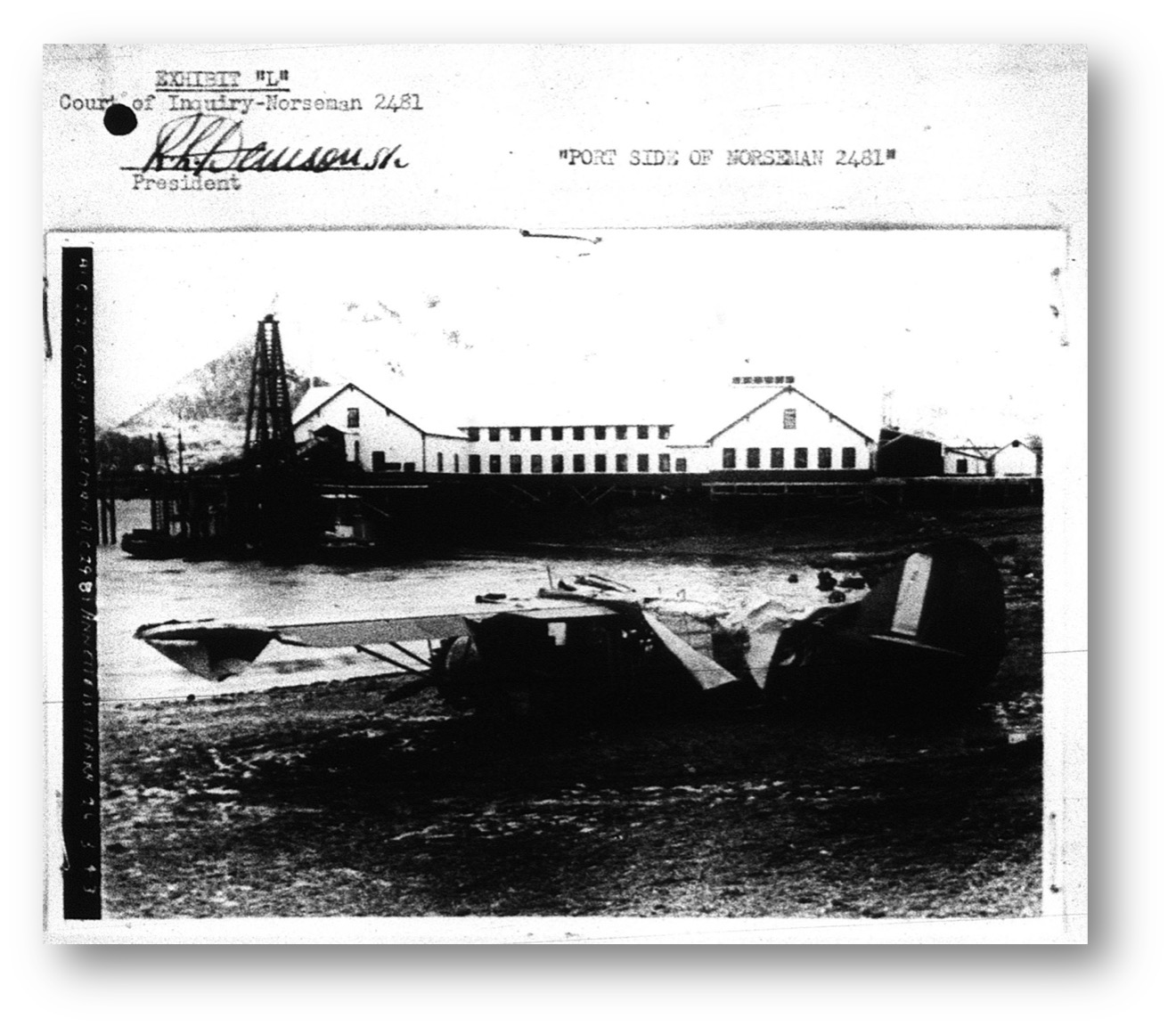

The first witness, S/L Ralph Albert Ashman, Commanding Officer of No. 115 (BR) RCAF Annette Island, Alaska since March 22, 1943, acting C/O of the Station in the absence of W/C G. Diamond, explained how he met, on March 25, Norseman 2481 at the dock at Annette Island. On board were the three USO entertainers who were scheduled to entertain all US and Canadian troops on the island before heading further north. S/L Ashman put the women’s luggage into the back of the RCAF station wagon. They all climbed into the car and drove to the US Army Post exchange store where he contacted Captain Rhude of the US Army who was accompanying the entertainers in their tour. Captain Rhude then asked if the RCAF could possibly fly the women to Ketchikan where they had some business to attend to. Ashman explained that it was possible, as the Station Equipment and Accountant Officers also had business to attend to in Ketchikan. “I informed him that the plane would be leaving for Ketchikan at approximately 1330 hours and instructed him to have the girls at the dock at that time. At approximately 1315 hours, S/L Curry who was to be the pilot, reported to the RCAF Operations Room to file his flight plan, obtain signals of the day, and check on the weather. I then drove S/L Curry, F/L Dowling, and F/L Stapleford down to the dock where the girls were waiting.” Light rain was falling. Visibility was at ten miles, with a gusty wind of approximately 15 to 20 mph in the bay. Ashman inquired of Curry as to the state of weather in Ketchikan. Curry replied, “Good.” Ashman said, “I instructed him that if he had any doubt as the state of the weather at Annette Island before returning, he was to phone me at the RCAF Headquarters.” S/L Curry, the two Flight Lieutenants, the three USO hostesses and LAC McMichael boarded the aircraft, which then taxied out preparatory to taking off. “F/L Stapleford, Station Accountant Officer, had gone to Ketchikan in connection with money matters, and in particular to make a bank deposit, as he was required to do at regular intervals. F/L Dowling, Station Equipment Officer, made a trip to obtain electrical supplies for the new hospital. The RCAF waiver form had been signed by the civilians in Prince Rupert.” At 1350, they headed to Ketchikan. When S/L Ashman left the Station Headquarters for the Officers’ Mess at 17:10, the light rain was still falling. However by the time he reached the intersection of A and B runways, a distance of approximately ¾ of a mile, the rain had turned to snow. “I proceeded on my way and by the time I had reached the Officers’ Mess, a total distance of approximately two miles from the headquarters, the snow has intensified to such an extent that it was barely possible for the windshield wiper to keep the windshield clear. I entered the Mess and stood talking for approximately 10 minutes to F/L Ellis. The phone rang and after answering it, I was informed that a phone call had been received from Metlakatla, an Indian village on the north side of the island.” He was told Norseman 2481 had crashed. “There was no trace of any of the occupants of the plane.” After informing the US Army Camp Commandant, Ashman then jumped into the station wagon along with F/L Ellis where they proceeded directly to the Operations Room requesting the Medical Officer to meet them at the crash site in the ambulance. The US Army crash boat also was to meet them there. By this time, the visibility cleared to about five miles. Norseman 2481 was nose down in the water, its tail sticking out of the water. A fishing boat brought the RCAF personnel closer to the downed aircraft. “Together with some of the Officers, I got in a row boat to get to the crash,” Ashman testified. “There was approximately six to eight feet of the rear of the fuselage protruding from the water. I could see the starboard rear door was open, although underwater. I obtained an oar and felt inside the rear compartment through the door, but without results.” The tide was ebbing, exposing a reef, which was just above the water. On the reef were a gas tank, and the door from the aircraft. Ashman returned to the boat and the skipper of the fishing boat informed him that a floating pile driver was being brought out to lift the wreck. Unfortunately, the wreckage could not be lifted high enough to extract the bodies, so Ashman ordered the skipper to tow the wreck to the beach at Metlakatla. “After arrival there, six bodies were removed. As there were seven persons on board when the aircraft left for Ketchikan, it was assumed one was missing and the crash boat, which had arrived, carried on a sweep of the area but without success.” It was getting dark and the snow started falling again, so nothing further could be done that night.

H.E. Scott, Radioman 1st Class, US Coast Guard posted at Ketchikan testified he was in charge of the radio at the US Navy Hangar. “My work entails control of all flights arriving at and departing from this unit and receiving and filing flight plans.” During his shift, he received information from the Army at Annette via teletype that RCAF Norseman 2481 had departed Annette for Ketchikan. “The plane arrived at 1420 hours and the pilot reported to me. I counted seven people getting out: three women, the pilot, two other officers and the crewman I had seen before. All these people, except the crewman went into town. The crewman did not leave the dock at anytime. At approximately 1530, the crewman asked me if I had the weather and asked me if it was closing in at Annette.” Something was unserviceable, and Scott was unable to tell him the weather. The passengers and pilot returned from town at about 1655. Scott saw the women and the pilot climb aboard the aircraft. “The pilot came over to the building and checked out. I asked him his name, which he said was Curry.”

Robert G. Hill, Observer in the US Weather Bureau in Ketchikan produced airway weather reports showing spots weather observations for Ketchikan at 1430, 1530 and 1630 hours on March 26, 1943. “These reports are required to be made by me or others in the performance of our duties. We keep official records known as ‘log pilot contacts.’” When asked if S/L Curry requested information on the weather that afternoon, Hill responded, “No. There is only one entry for that afternoon and that was a request from Ellis Air Transport.” He said they did not make a spot weather observation for 1730 hours. Hill spoke with Curry. “I asked him how many would be in the plane. He told me, ‘Seven: myself, three women, two Officers and one crewman.’ The pilot then got in the pilot seat and the crewman got into the rear door, and a second later, stepped out again onto the pontoon and put on his life preserver. He then let go of the line. “The pilot started the motor and I saw the crewman crawl into the plane through the rear door, which he then closed. The plane then taxied away for the take-off. The plane left the dock at 1700 hours.” When asked if Curry had asked Hill anything about the weather, Hill replied, “No. If he had, I would have called the Army here who in turn can contact Annette and we would have got it for him.” Hill described the weather and visibility for half an hour preceding 1700 hours for the court: “The weather here remained the same during that period. Winds were southeast about 20 mph and gusting with visibility about five miles. I could see the mountains on Gravina Island, which I estimate is about five miles away. The mountains behind Annette Island were obscured and the weather in that direction looked ugly and threatening.”

Nineteen witnesses were called over the course of the Inquiry: residents of Metlakatla, fishermen, RCAF and US Army personnel. The instrument mechanic and the electrician declared Norseman 2481 serviceable. The airframe mechanic said he carried out the daily inspection of the airplane with the assistance of LAC McMichael that day. The plane was sound.

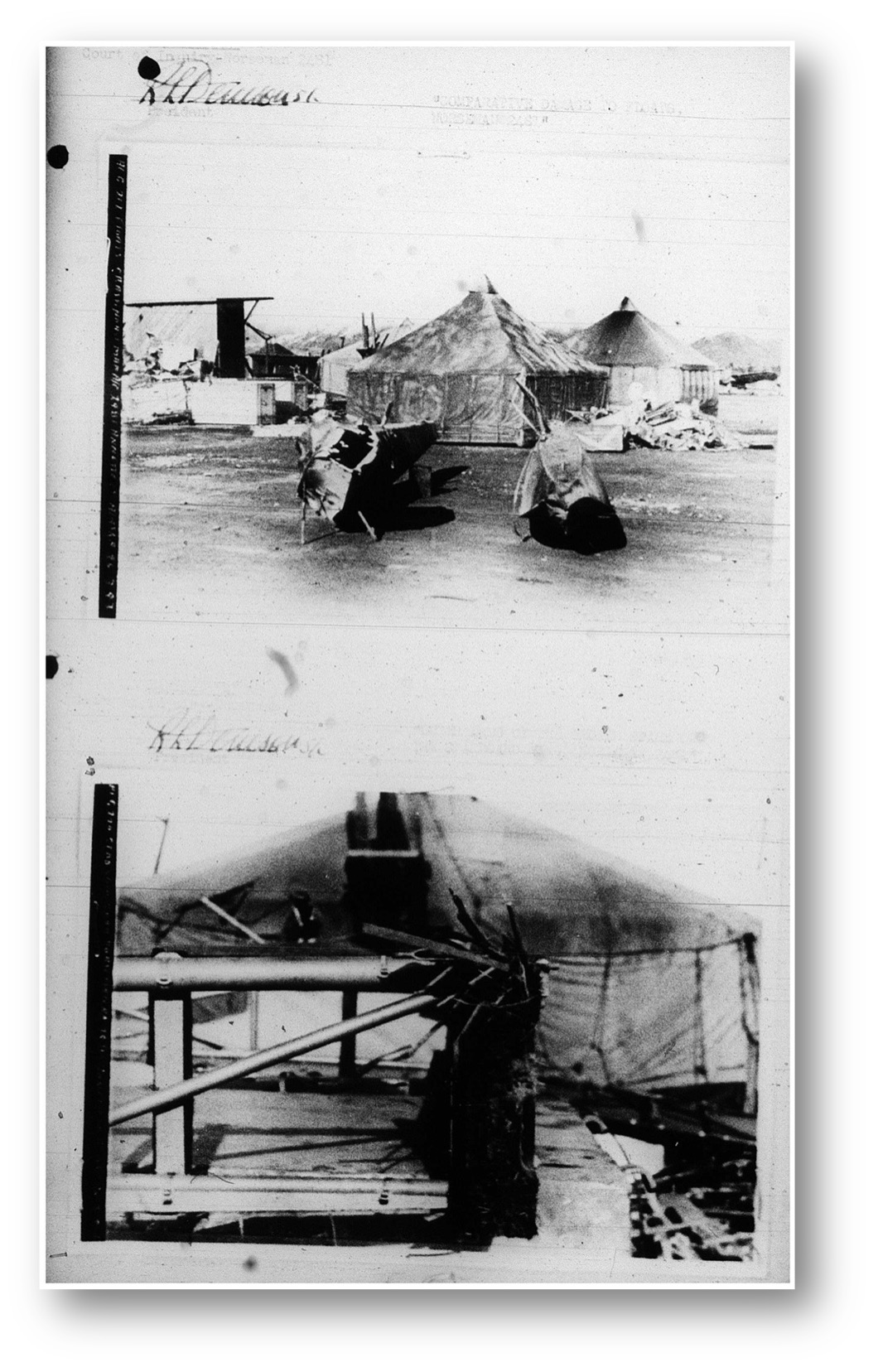

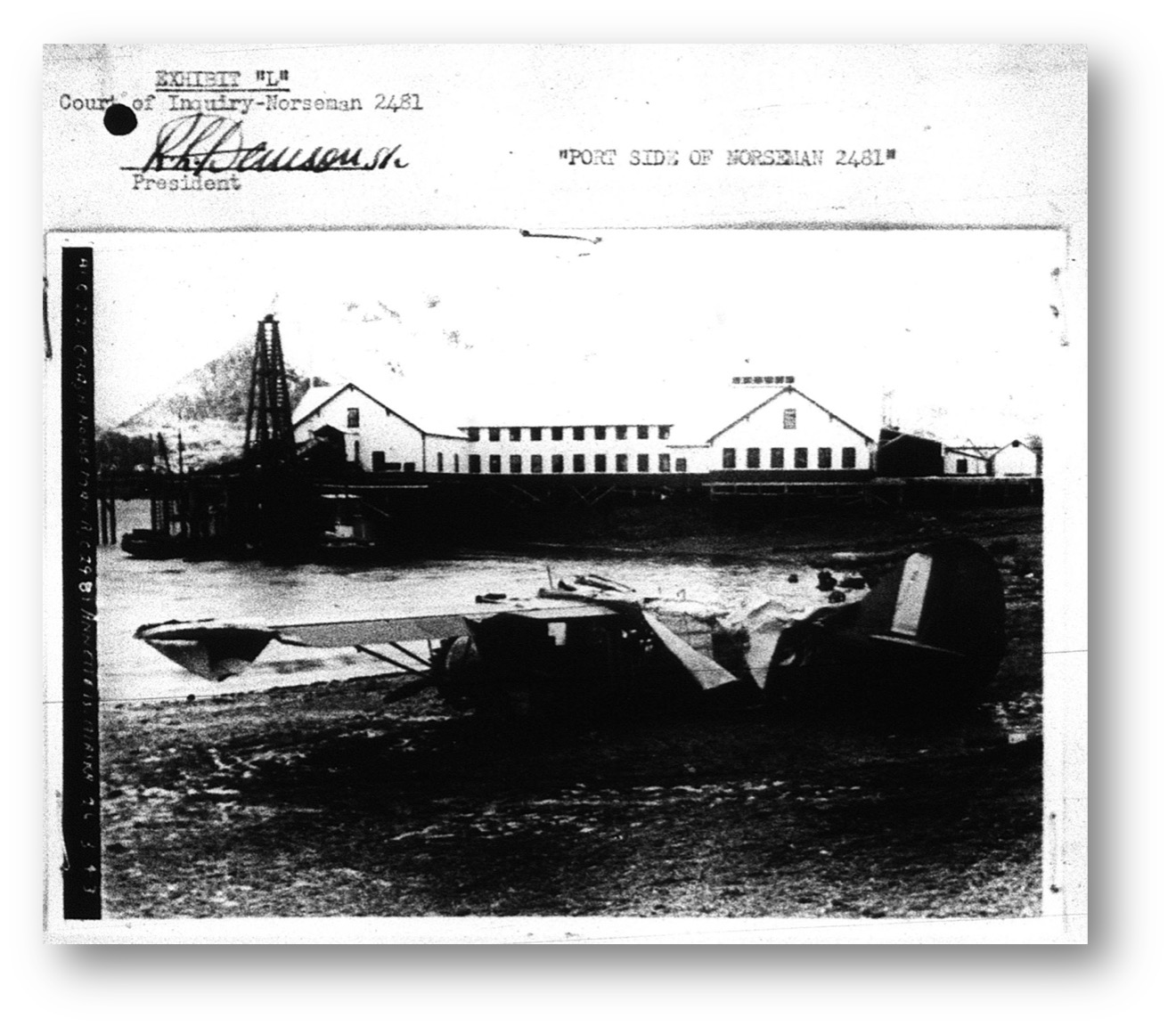

The Chief Engineering Officer, F/L W. H. Lewis inspected the wreck. He said: “Wing, tailplane, float and side of the fuselage on the port side of the aircraft appeared to have sustained little damage. The engine was complete, with the exception of the cowl ring and appears in fairly good condition. The propeller was in good condition and in coarse pitch, with the tips of the blades bent slightly forwards and scored, presumably cutting the starboard float. The starboard side of the fuselage showed signs of impact such as broken windows. The tip of the starboard tail plane of the fuselage was crumpled although the fin and rudder had retained its shape comparatively well. The control column is broken at the junction of the Y and the upper portion was forced over to the right-hand side of the cockpit. The instrument panel was almost completely intact.”

John Charles Hudson, fisherman, was one of the men who assisted in bringing the aircraft from the place of the accident to the beach. “I waded out and opened the rear left compartment door, which while not stuck, was firmly closed, and I had to turn the handle to open it. The right-hand front door was not on the plane, but all the other doors were on, and to the best of my recollection, closed. I got inside the plane and saw four bodies, all of them being strapped to their seats. Three were women and one a man. All the seats had been partly torn away from their fastenings. I noticed that the fifth seat, which was at the rear, was not occupied, and the safety strap was not done up. They were not torn loose or broken. “I then released the belts holding the four bodies and handed each body out the door. I took out the bodies of two of the women, then the body of a man who was a very thickset heavy man (the heaviest of the three men), and then the body of the third woman. “It was getting dark by now, and getting difficult to see, so we got more lights put on the scene, and I got a flashlight. I then noticed there were other bodies in the front part of the plane, which I hadn’t noticed before, because of the debris. I pulled the debris aside and went forward and found bodies of two men. They were sitting on the two seats, not strapped in. The one on the right hand side was passed out to Billy Booth and the one on the left was passed out the left front door. The one on the left hand had the fingers of his right hand locked around a big knob on the dashboard which had ”Pull to turn” on it. I could see no sign of physical damage to him, although the one on the right had his forehead cut. One of the Canadian officers told me there was supposed to be another one there, and to take a good look. I made a careful search, pulled wreckage aside and flashed my light everywhere, but there was no trace of another body.” When asked if there was another hole besides the front door large enough for a body to go through anywhere on the plane, Mr. Hudson answered, “No.” He added, “It would be impossible for a body to get from the back compartment to the front, as there was too much wreckage between. I had quite a hard time ripping the wreckage aside to get through. No one had been in the aircraft before me. I was the first person to open the door and get in the aircraft.”

When the Chief Engineering Officer continued with his testimony, he said, “The aircraft was trimmed in the nose down position approximately 3/8” from the neutral position by the indicator. This was also substantiated by the position of the trim tail of the elevator. The carburetor gauge was stuck indicating 35o F. The carburetor heat control was in the ‘full on’ position. The throttle was in the position, which would normally give about 1800 PRM. The Gyro horizon indicated full right wing down and the vertical speed indicator was stopped at 200 feet/minute descent.”

Mrs. Ed Leask, housewife and a resident of Metlakatla said, “Shortly after 5 o'clock on the afternoon of 26 March 1943, I was working in the kitchen of my home, the window of which directly overlooks the waterfront and out towards Gull Island area. I heard the sound of an aeroplane and looking out, I can see it coming from the direction of Ketchikan. It was flying low and in spite of the heavy snow I can see the red, white, and blue target on the side of the aeroplane. It disappeared and a few minutes later I saw it coming back from the opposite direction, and flying at about the same height. I watched it disappear into the snow when suddenly the engine stopped dead. It was so unusual that I thought something must’ve happened. It was about a minute from the last time I saw the airplane until the engine stopped. I could hear the engine plainly as I was leaning out the window. I could not see the reefs or nearby islands in the vicinity because it was snowing much too heavily.”

William Booth, the seventh witness, and the skipper of Mermaid was the first on the scene. He concurred with Mrs. Leask. He added, “The plane flew on in a northwesterly direction in a level flight more or less in the direction of Ketchikan, and disappeared in the snow, but I could still hear the engines. Very shortly after, the engine seemed to become louder and higher in sound, and then suddenly seem to be smothered out. I didn’t hear any crash; but thought the plane must’ve hit the island, because of the roaring and sudden stop of the motors.”

Albert Wellington, fisherman in Metlakatla was another one of the first responders. He said, “When we arrived, Mr. Hayward who came with us, rowed over in a small boat with me to investigate the wreck. About four feet of the fuselage and the tail were sticking out of the water. We circled the plane in our boat and looking through a hole in the fuselage to see if we might be able to rescue anybody inside. We couldn’t see anything, but we stood by while Mr. Booth went back to the dock to get help. We noticed bits of wreckage 50 feet or more upwind of the crash. The Mermaid returned to the crash and then we went back on it to the dock to see about getting the pile driver to raise the aircraft from the water. As I worked on the driver, I went out with it to the wreck, and help to raise the aircraft.” He said once they raised the aircraft partway out of the water and dragged it to the beach, it was about 9 o’clock.

From the above observations, F/L Lewis, Chief Engineering Officer concluded, “The aircraft was descending with power on, as indicated by the bending forward of the propeller tips as they entered the water; the aircraft struck the water with the starboard wing, breaking the wing upwards and backward, releasing the starboard fuel tank. As the starboard wings struck the water, the nose of the aircraft dropped, allowing the forward portion of the starboard float to strike the water with the starboard side. The damage to the starboard side of the fuselage was the type that would be the cause of impact with a smooth semi-resisting object.”

From the Court of Inquiry: 1. The weather at the time of departure was not entirely satisfactory, and the court finds that the pilot was negligent in commencing the trip without obtaining information from the RCAF station Annette Island Alaska, as he had been asked to do, or from the Navy dock personnel. 2. The storm was of a very considerable density, consisting of large wet flakes of snow likely to quickly accumulate against the windshield and render forward visibility almost impossible. Apart from this factor, visibility was reduced to almost nil. 3. The pilot in these circumstances decided to make an emergency landing. Fixing his position from Metlakatla, he flew northwest at a very low altitude preparatory to turning into wind. Conditions of visibility were now so extreme that the pilot had no way of estimating his height above water. The court is unable to say whether the pilot was negligent in not returning to Ketchikan, as extreme conditions the weather may have prevented that course of action. 4. The cause of the accident was in our opinion that the pilot while attempting to turn to starboard to come into the wind to make an emergency landing in the circumstances described above, misjudged his distance from the surface with the results of the starboard wing or float of the aircraft violently struck the water, and the aircraft crashed into the sea. There appears to be no doubt that the pilot in this instance was responsible, first for not having obtained the weather report prior to leaving Ketchikan for Annette Island, and secondly for flying into a snow storm rather than attempting to skirt same, or returning to Ketchikan.

The following were the recommendations for prevention of a repetition of this type of accident: 1. That all pilots, regardless of seniority or experience, be impressed with the extreme importance of obtaining absolutely all available information regarding weather conditions along the route and at point of destination before taking off, and if there exists the slightest element of doubt, pilots will not take off until conditions improve. 2. Unless it is imperative to return to base, pilots must be warned not to fly into squalls or hazardous weather conditions. The safest action is to fly reciprocal course and on emerging into clear visibility, decide whether to go around or return to the point of departure.

The Court further found: 1. That all RCAF personnel were on duty. 2. That LAC McMichael was an occupant of the aircraft at the time of or immediately before the crash. It is the opinion of this Court that McMichael lost his life in the crash.

The three RCAF Officers were taken to the Canadian hospital. F/L V.W. Pepper, Senior Medical Officer at Annette Island said, “These men may have been killed in the crash. Almost certainly, they were stunned and which case, they drowned. It is impossible to say definitely which factor was the immediate cause and no autopsy was performed.” An American ambulance took the USO entertainers away to the US hospital. The American authorities took over their cases.

Two days later, the bodies of Kaiser, Gloeckner and Street, along with those of Dowling and Stapleford would be flown to Vancouver and/or Seattle in a DC3 with two Kittyhawk airplanes as escort. Curry was cremated, his ashes dispersed on a mountain on Annette Island.

And McMichael? He was in the back of the plane, farthest from the point of impact. Did he unbuckle himself and attempt to exit the plane, only to drown and be carried away by the Bering Sea?

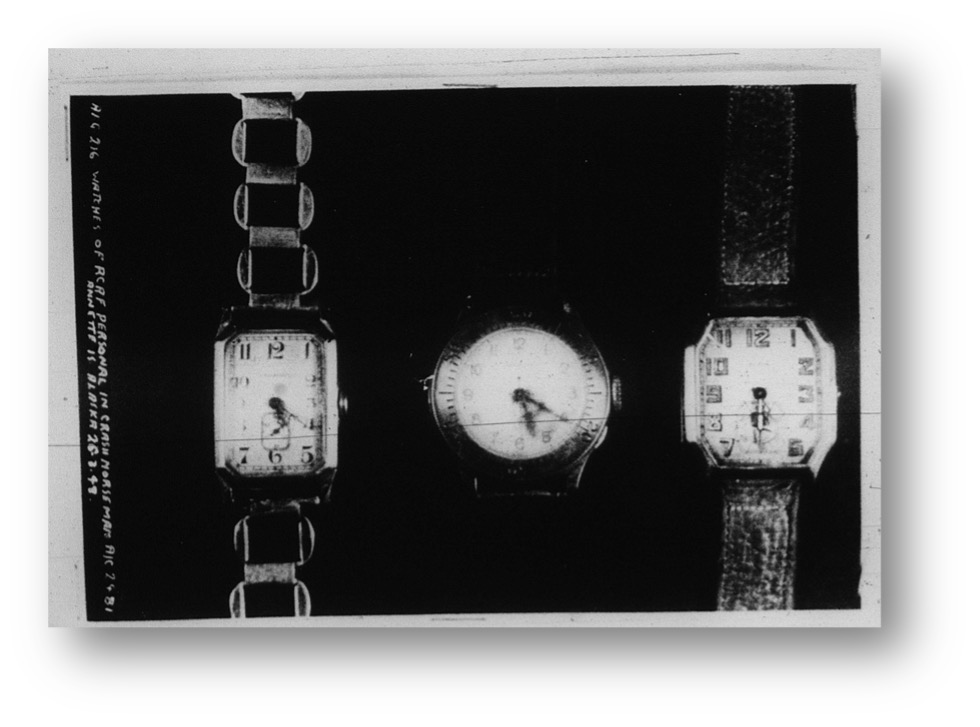

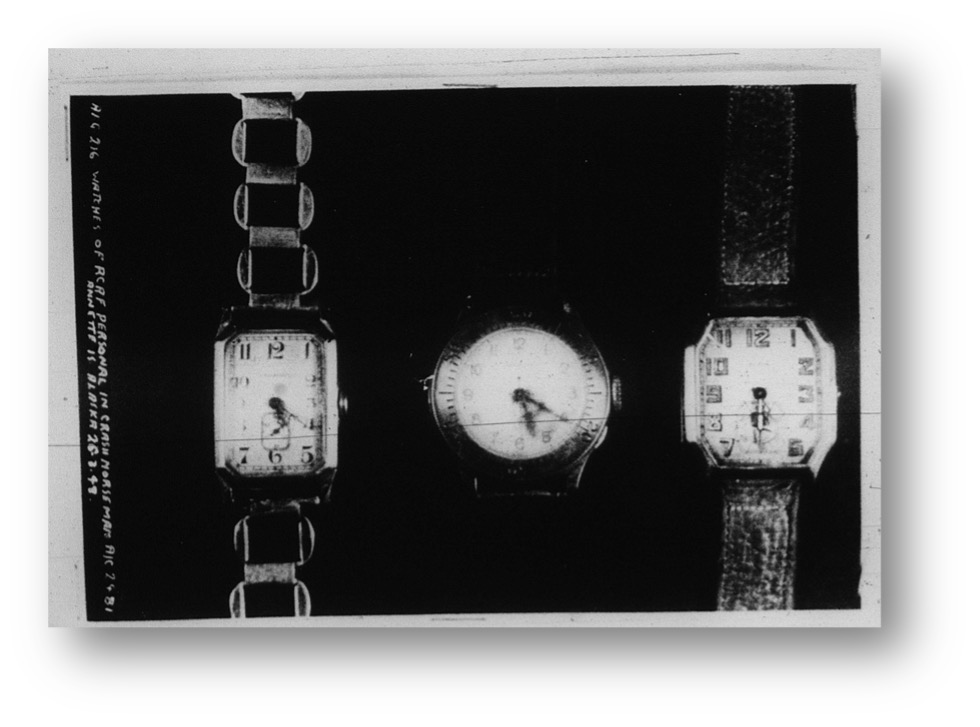

When Gerry was six years old, Hazel married her brother-in law, Frank. Ted is remembered within the McMichael family through his medals, his watch, many photos, newspaper articles, letters, and stories.

The full story of Norseman 2481 can be found in Quietus: Last Flight by Anne Gafiuk, available through the author, local libraries, and the Bomber Command Museum of Canada in Nanton, Alberta.

LINKS: