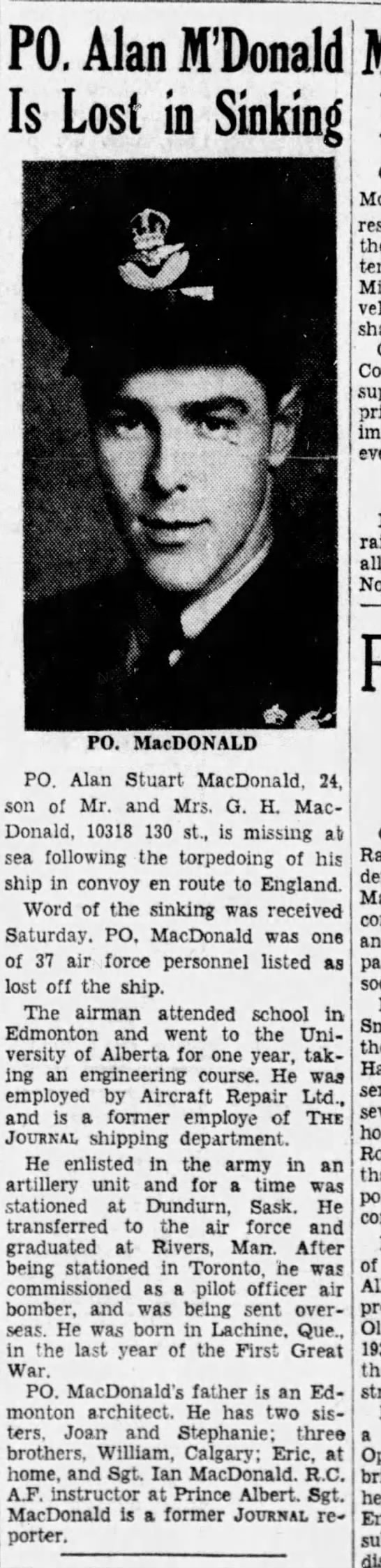

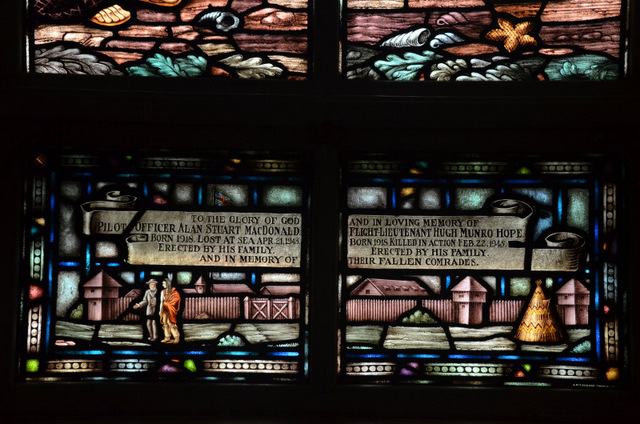

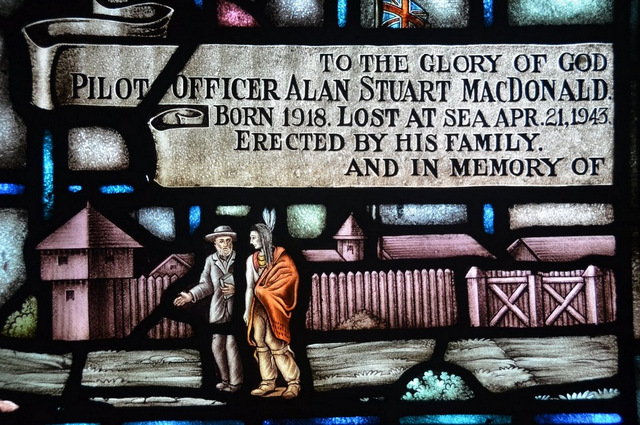

December 15, 1918 - April 22, 1943

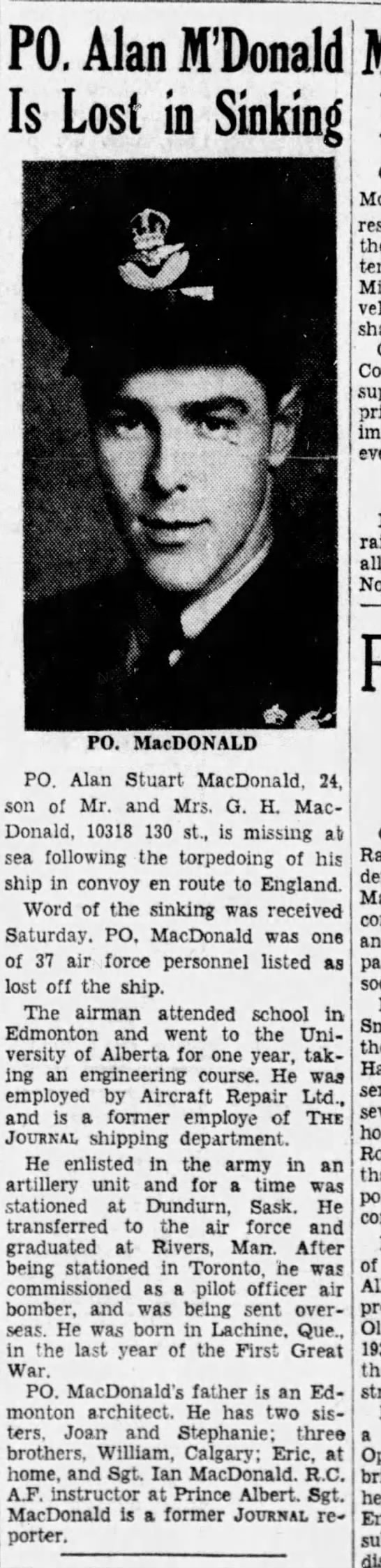

Alan Stuart MacDonald, born in Lachine, Quebec, was the son of George Heath MacDonald, and his wife, Dorothy Enid (nee Huestis) MacDonald of Edmonton, Alberta. He had three brothers (William MacDonald, Calgary, Ian Charles MacDonald who was in the RCAF in Edmonton, and Eric MacDonald, still at home attending high school) and two sisters (Joan Whitman Wilson, Jasper, Alberta and Dorothy Stephanie MacDonald, civil service, Edmonton). The family was Anglican.

He had senior matriculation and attended the University of Alberta with one year Engineering, in Edmonton. Prior, he had six months at McDougall Commercial, learning bookkeeping and typing.

Alan worked for the Edmonton Journal, mailing and distribution in the summers 1934-1938, then as a window dresser at T. Eaton Co., Edmonton in 1939. He was a rodder (surveying) with Dominion Government Survey, Alberta in 1940, then for the Department of Munitions and Supply in Edmonton, as a stockman and office clerk, but also and doing aircraft maintenance for six months. He planned to return to university and study engineering (research).

Alan first enlisted with the Canadian Army in August 14, 1941, first stationed at Camrose, Alberta, then at Dundurn, Saskatchewan. For two days in July, he was at the Dundurn area hospital. While with the army, he worked in the company orderly room, as a clerk. He indicated that he discontinued his engineering studies because of money.

Alan enlisted in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan on December 13, 1941, not quite 23 years old while a soldier with the Canadian Army (Royal Canadian Engineers Training Centre). “Seems to be very good type of applicant. Intelligent and mannerly. Good cardi-vascular and neuro-muscular efficiency. Fit for aircrew duties. Co-operative, composed, keen and alert. Vision and ocular poise good.”

The interviewing officer wrote: “Young man with high educational qualifications and fair outside experience. Neat, well mannered.”

Alan stood 5’ 6¾” tall, weighing 141 pounds. He had brown eyes and brown hair, with a dark complexion. Alan had a mole ½” left of 8-9th thoracic spine, plus a sar on his right temple. He was right handed. “Head cold about every four months with convivial nasal blockage and discharge.” This condition seemed to be somewhat of a concern to the Medical Officer, but when looked at by a specialist, Alan’s nose and sinuses were thought to be free of active infection.

He enjoyed hockey, swimming, basketball, track and tennis. He was a swimming champion. He smoked ten cigarettes a day for the past five years and indicated that he drank alcohol occasionally. Sports and reading were his hobbies. Alan knew how to drive a car.

The RCAF accepted Alan, sending him to No. 2 Manning Depot, Brandon, Manitoba December 30, 1941 until February 13, 1942.

Alan was at No. 14 SFTS, Alymer, Ontario until April 11, 1942. On April 28, 1942, he was at No. 6 MSB, Medical Selection Board. “Good physique, past scholastic record not good. Failed year at university. Applied himself poorly; however, bright, alert, and mental ability if applied is probably good, had not particular interest in flying and even now, no desire to be pilot. Motivation for observer is fair only; this will require augmentation or it will not be sufficient to keep him working hard enough.”

Alan was sent to No. 6 ITS, Toronto until June 6, 1942.

He was sent to No. 2 Air Observer’s School, in Edmonton until October 23, 1942. “Appearing on parade in a state not becoming an airman.” Punishment was two days confined to barracks.

Trenton was his next destination to Composite Training School for about one month, often when individuals wash out of their training.

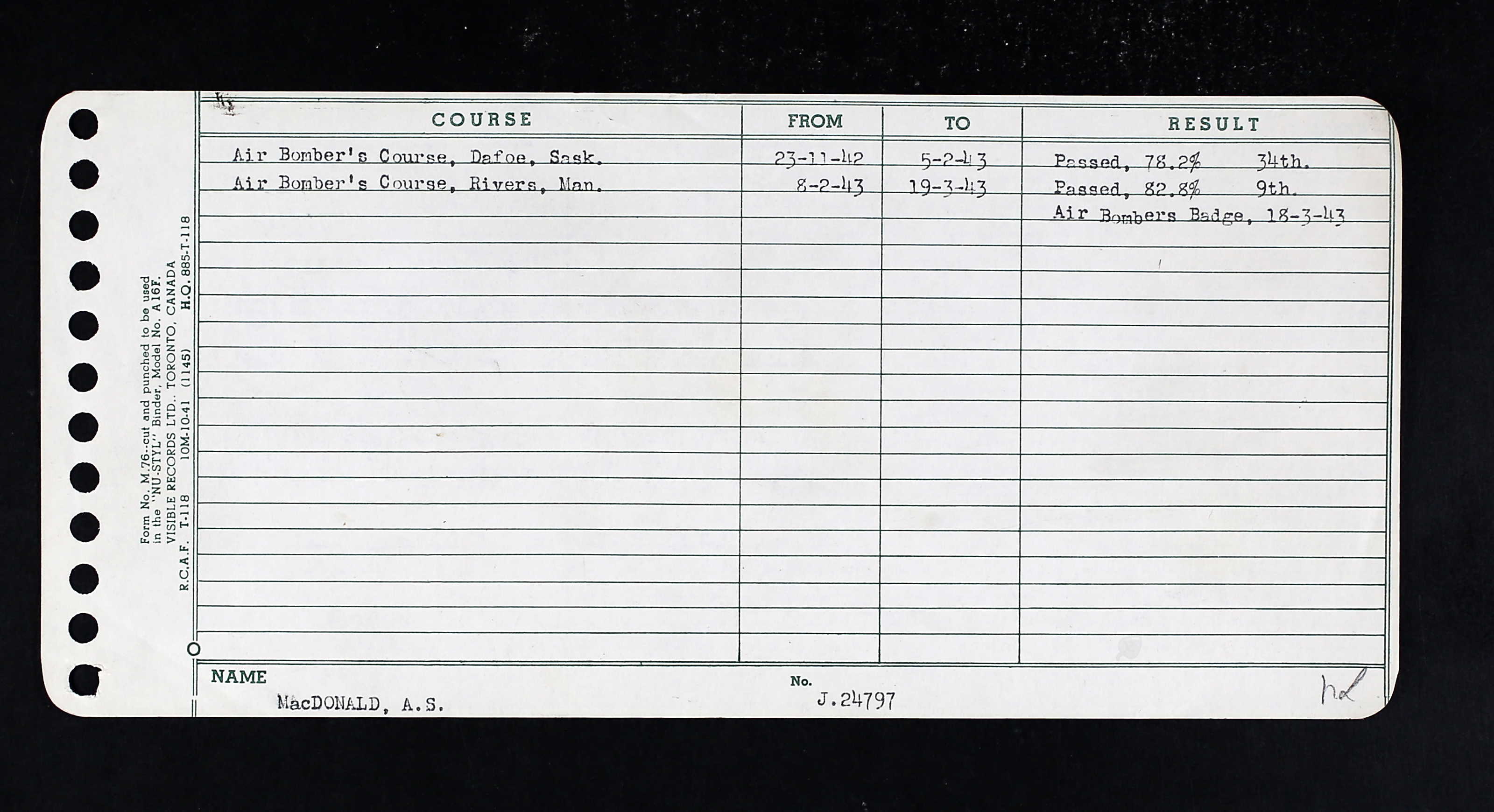

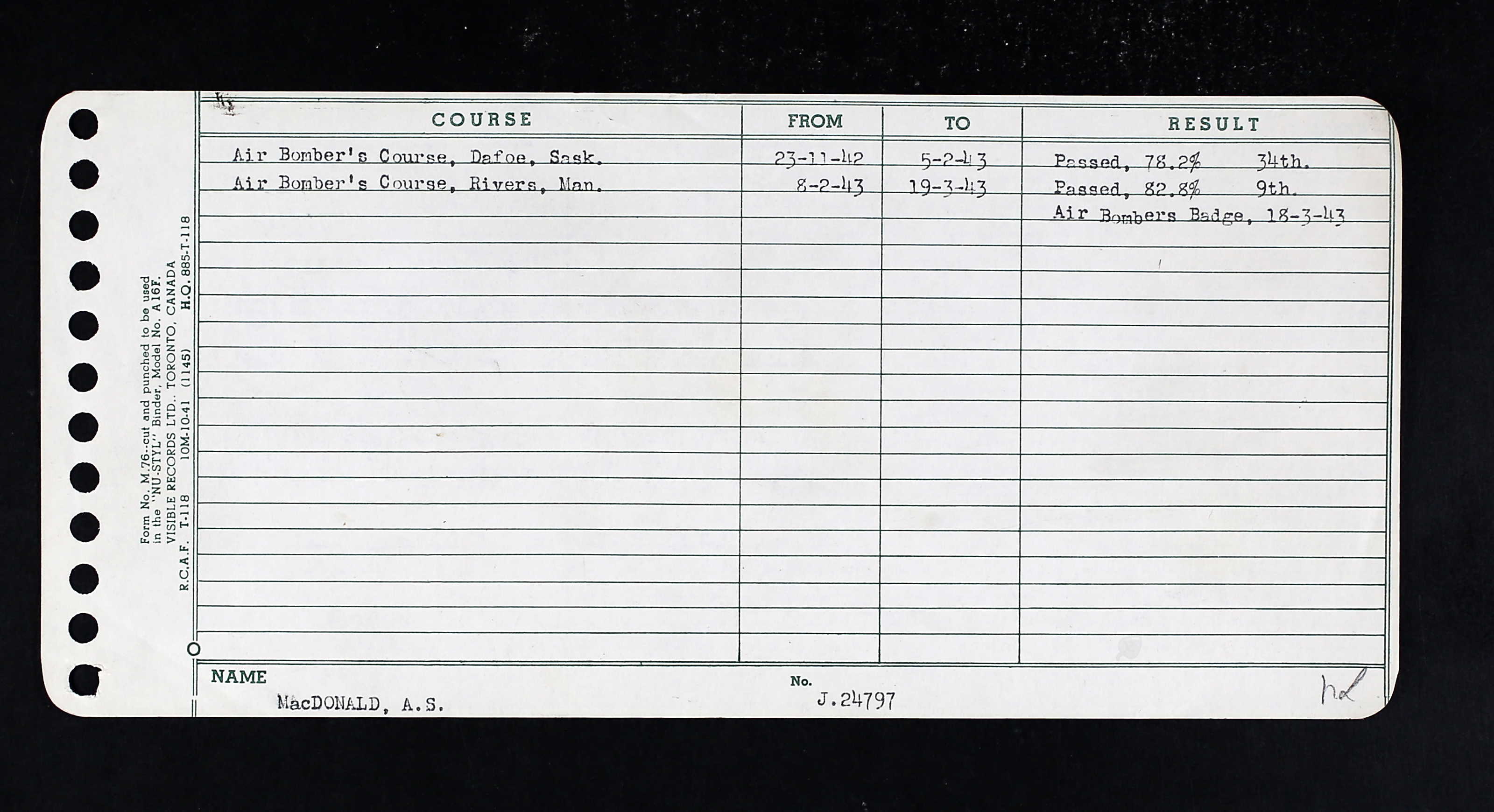

Dafoe, Saskatchewan and No. 5 Bombing and Gunnery School was next and he was there from November 21, 1942 until February 6, 1943, where on March 18, 1943, he earned his Air Bomber’s Badge. 78.2%. “Bombing: Average in air work. Above average in ground subjects. Gunnery: Average in air work. Above average in ground subjects. General: Has shown a keen interest in this course. Displays initiative but needs more self confidence. Passed a supplementary signals examination.”

Then Alan was sent to Rivers, Manitoba at No. 1 CNS for two months, taking another air bomber’s course, with an 82.8%. “Navigation: Very co-operative with rest of the crew. Work is fairly neat. Armament: Above average. General: A cheerful willing worker.” Alan was recommended for commission.

Alan had a policy with the London Life Insurance Co. for $5,031, his mother beneficiary. In 2021, that would be worth over $75,000. However, the number of premium paid would affect the outcome.

On April 4, 1943, Alan was in Halifax, Nova Scotia at Y Depot, then associated with RAF Trainees’ Pool by April 13, 1943, awaiting a ship to take him and others overseas.

On April 22, 1943, Alan was aboard the Amerika, British Motor merchant ship. It was on its way from Halifax, Nova Scotia to Liverpool. It was torpedoed as the ship was heading to Britain. It was a straggler in convoy HX-234. Thirty-seven men, all officers in the RCAF, were presumed missing as a result of enemy action at sea; sixteen were landed at a British port after their ship was sunk by U-306, south of Cape Farewell, off Greenland. Forty-two crew members and seven gunners were also amongst those who were lost. The master, Christian Nielsen, 29 crewmembers, eight gunners, and sixteen passengers were picked up by the HMS Asphodel, and landed at Greenock. General cargo, including metal, flour, meat and 200 bags of mail were also lost.

On May 5, 1943, Mr. and Mrs. MacDonald received a telegram. “Regret to advise that your son Pilot Officer Alan Stuart MacDonald...is reported missing as a result of enemy action at sea. Letter follows.”

Mr. MacDonald received a letter dated June 26, 1943 from F/L W. R. Gunn, RCAF Casualties Officer for Chief of the Air Staff. "Since my letter of May 6th, no additional news has been received. Attached is a list of the names and next-of-kin of sixteen Royal Canadian Air Force officers who embarked on the same ship as your son and following enemy action at sea were safely landed in the United Kingdom. The following official statement was made in the House of Commons....’I have been in receipt of communications from a number of members of this house and from people outside with reference to rumours regarding the recent loss of a number of members of the RCAF by the sinking of a ship in the north Atlantic and I desire to make the following statement on the facts. The vessel in question was a ship of British registry of 8,862 tons, designed for peace-time carriage of both passengers and freight, and having a speed of fifteen knots. She carried a crew of 86 and the passenger accommodation consisted of 12 two-berth rooms with bath and 29 other berths, providing cabin accommodations for 53 passengers. She was fitted with lifeboat capacity for 231 and travelled in naval convoy. Under the recently revised regulations agreed to by the United States authorities, the joint United Kingdom and United States shipping board, the Admiralty, the Air Ministry and the Canadian authorities, a vessel of this description travelling in convoy is permitted to embark as crew and passengers a maximum of 75% of the lifeboat capacity. The lifeboat capacity as stated above was 231, 75% of which is 173. Personnel on board consisted of the crew of 86, and RCAF personnel numbering 53, a total of 139, well within the prescribed limits. Because of the superior type of available passenger accommodation, the speed of the ship and the provision of naval convoy, the offer of the entire available space to the RCAF was immediately accepted. Rumours to the effect that this was a slow freighter not suitable for passenger accommodation are, of course, not in accord with the facts. Every precaution was taken to safeguard the lives of these gallant young men. It should be pointed out that on account of the serious shipping shortage every available berth on such ships must be used, and had the space not been taken up by the RCAF officers of the other arms of the services would have been placed on Board. It should also be stated again that the submarine is still the enemy’s most powerful weapon and that the Battle of the Atlantic is not yet won. Any ocean trip today in any part of the world is fraught with danger and I think I may safely say that our record in transporting our soldiers and airmen to the United Kingdom is one of while we may all be proud. No one deplores more than I do the loss of 37 of the finest of our young men who gave their lives for their country as surely as if they had done so in actual combat with the enemy, and I extend my deepest sympathy to their loved ones in their bereavement.’ If further information becomes available, you are to be reassured it will be communicated to you at once. May I again extend to you my sincere sympathy in this time of great anxiety."

After the sinking of the Amerika, the Canadian Pension Commission was concerned that there might be liability against the British Ministry under the Air Training Agreement and it was considered advisable to have British application forms completed should an application be filed by the parents of those who were lost aboard the Amerika.

On January 12, 1944, Air Marshall Robert Leckie wrote to Mrs. MacDonald to inform her that Alan was, for official purposes, presumed to have died on Active Service on April 22, 1943.

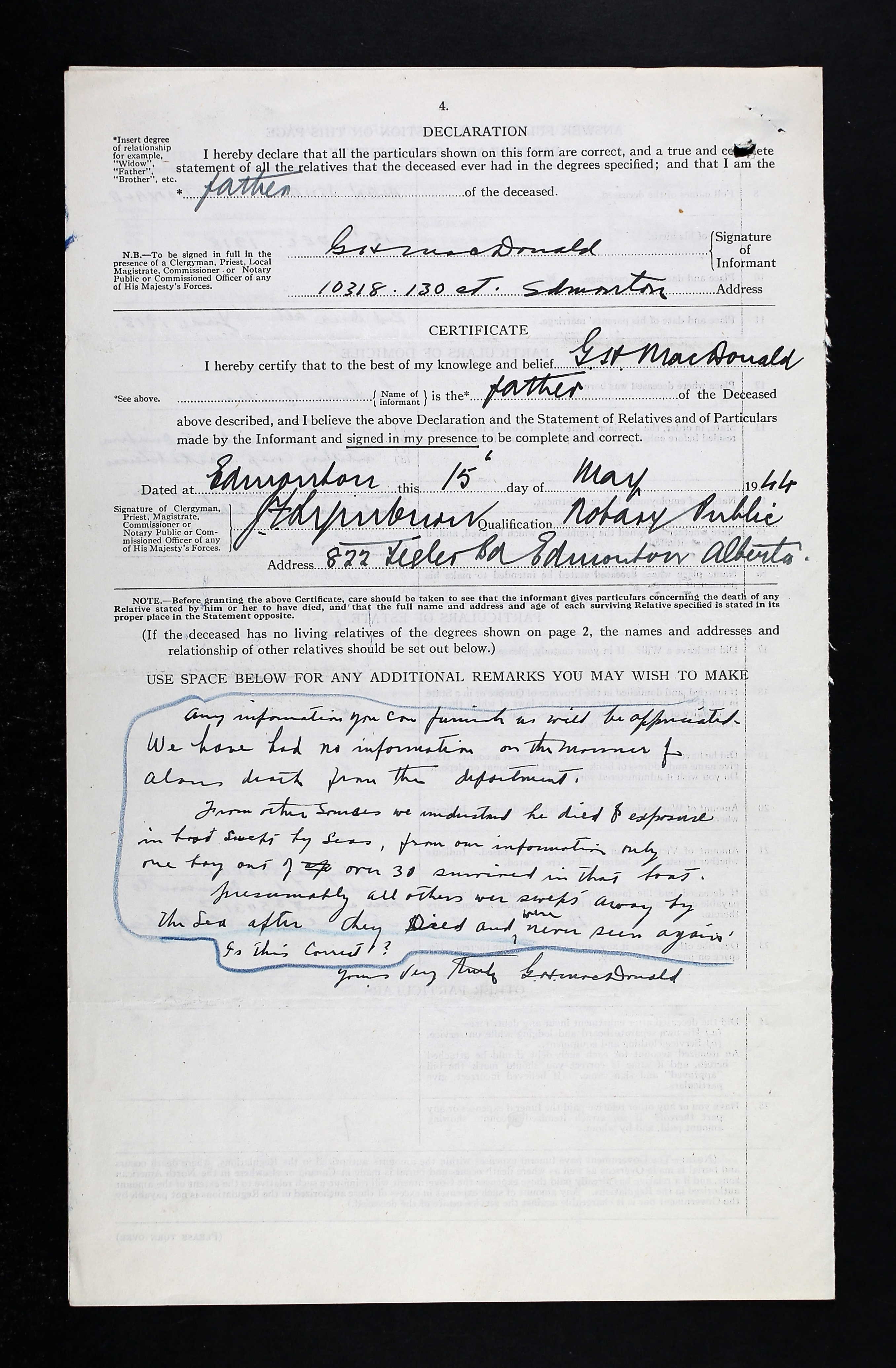

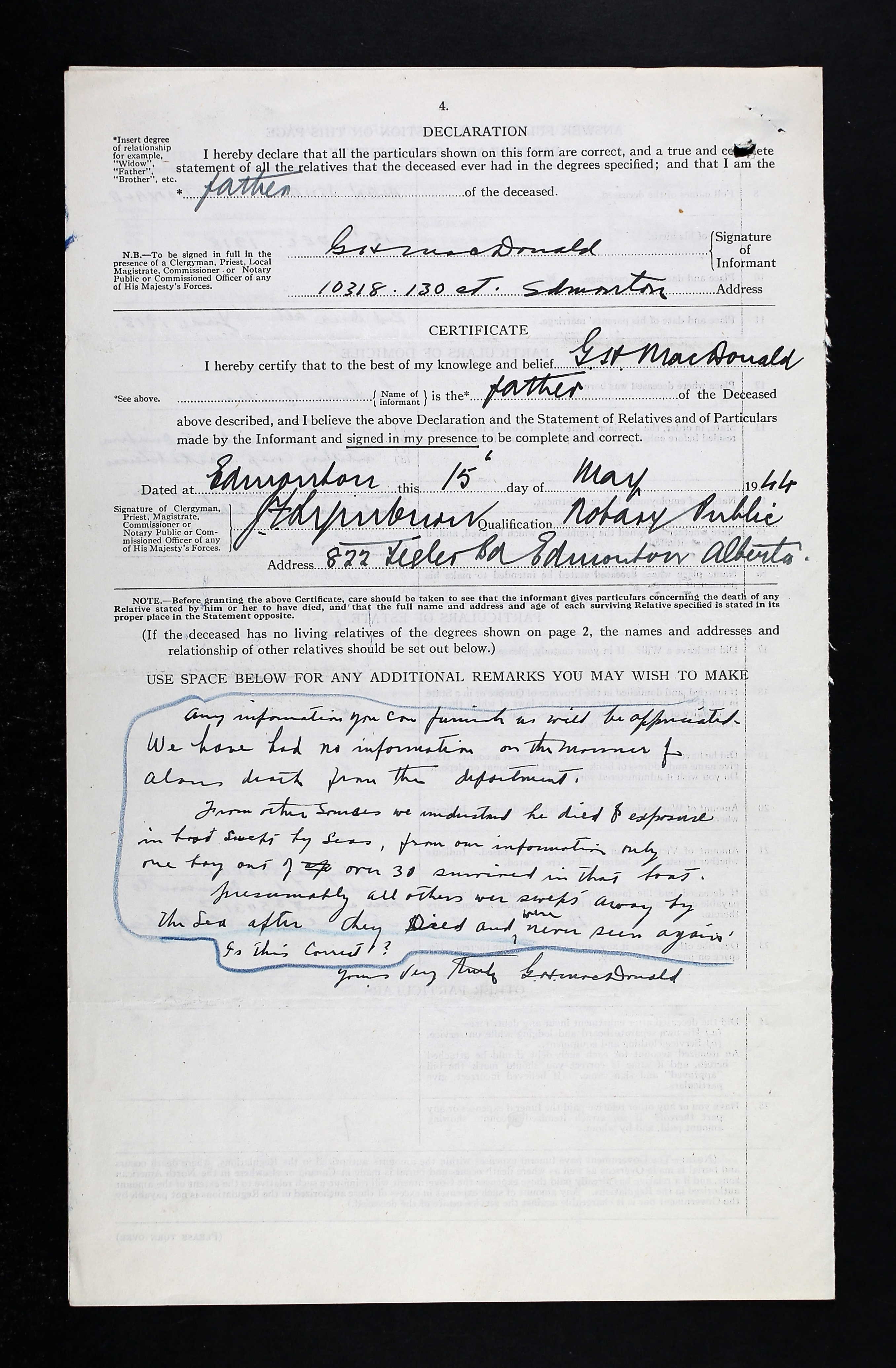

In May 1944, Mr. MacDonald was filling out a detailed form for the Estates Branch. He wrote: "Any information you can furnish us will be appreciated. We have had no information on the manner of Alan’s death from this department. From other sources, we understand he died of exposure in boat _____ by seas. From our information, only one boy out of over 30 survived in that boat. Presumably, all others were swept away by the sea after they did and were never seen again. Is this correct?"

In October 1955, Mrs. MacDonald received a letter from W/C Gunn informing her that her son’s name would appear on the Ottawa Memorial.