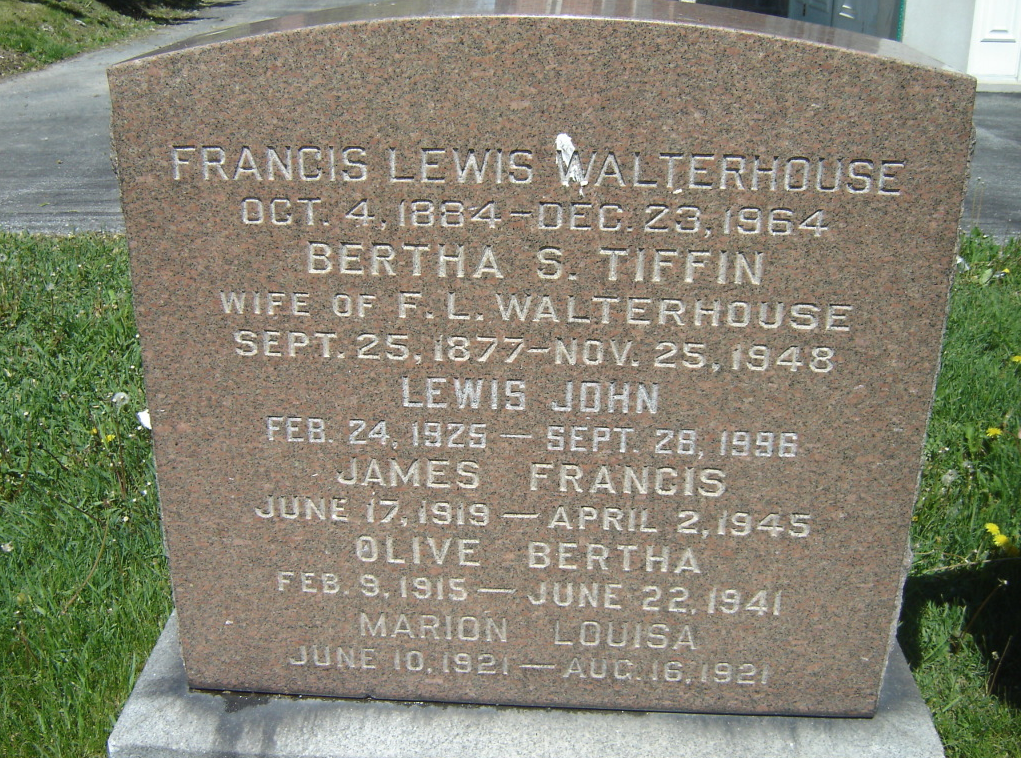

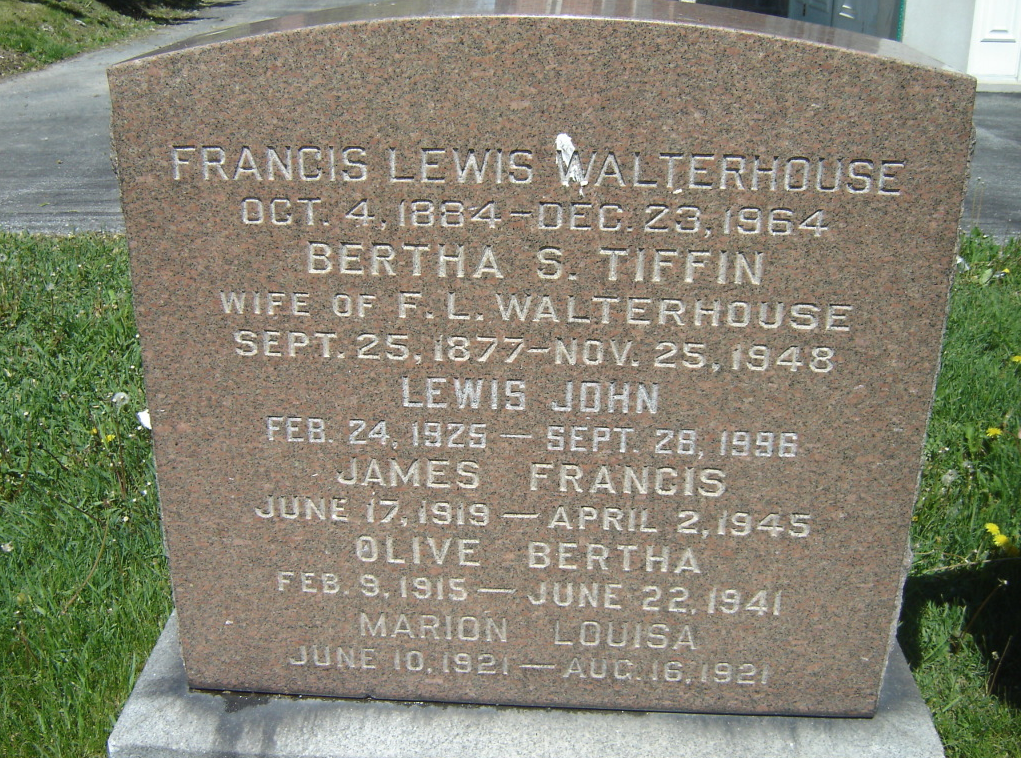

June 17, 1919 - April 2, 1945

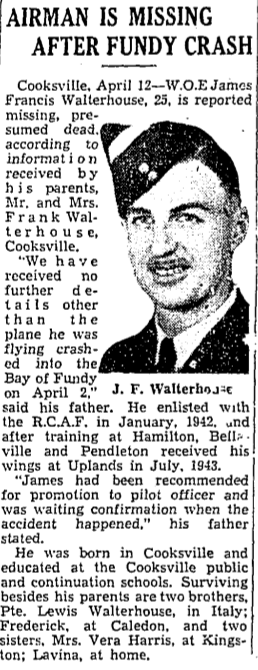

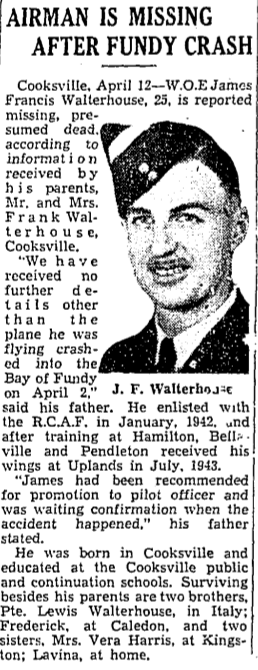

James Francis Walterhouse was the son of Francis Lewis Walterhouse (1884-1964) and Bertha Susanna (nee Tiffin/Tiffen) Walterhouse (1877-1948), Cooksville, Ontario. His siblings were Frederick Lewis Walterhouse (1913-1982), Olive Bertha Walterhouse (1915-1941), Marion Louisa Walterhouse (1921-1921), Vera Margaret Harris, and Lewis John Walterhouse (1925-1996). The family attended the United Church.

In a letter from the principal of Cooksville Continuation School, after two years at high school, June 1935, he left school “of his own volition to earn his living.”

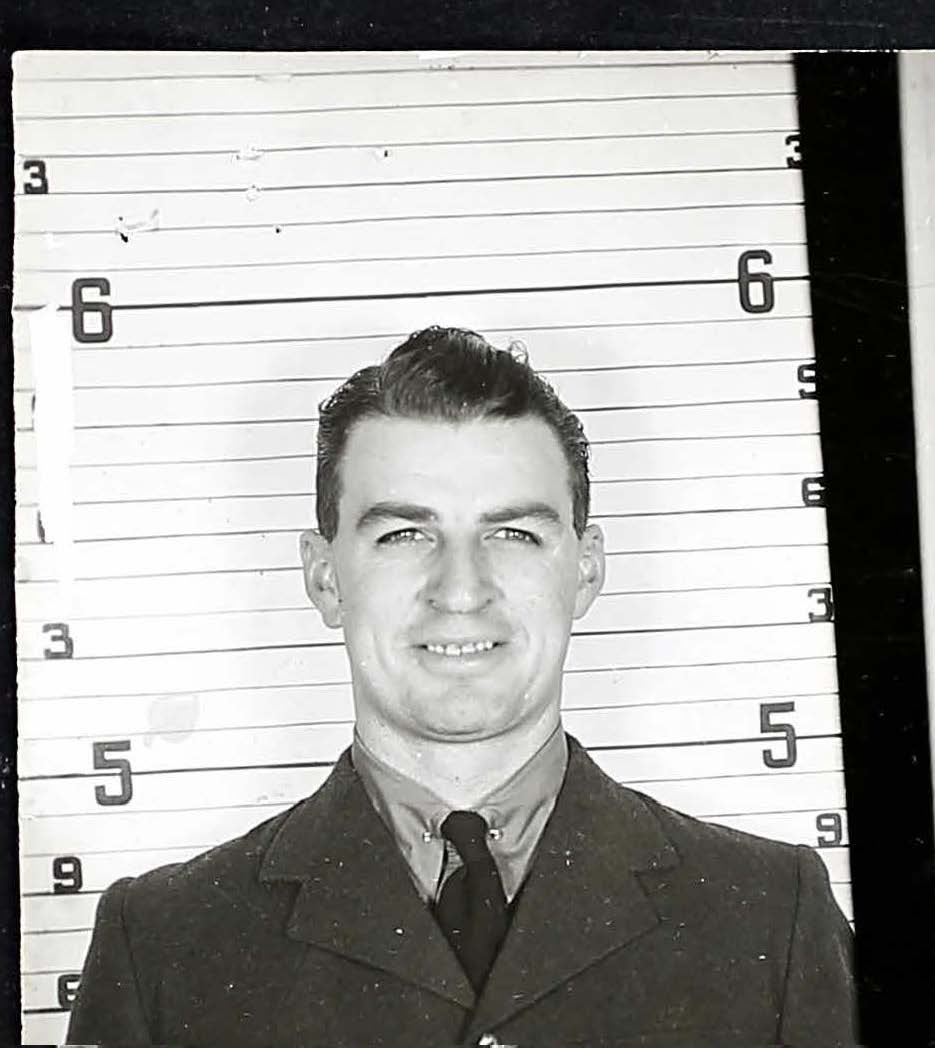

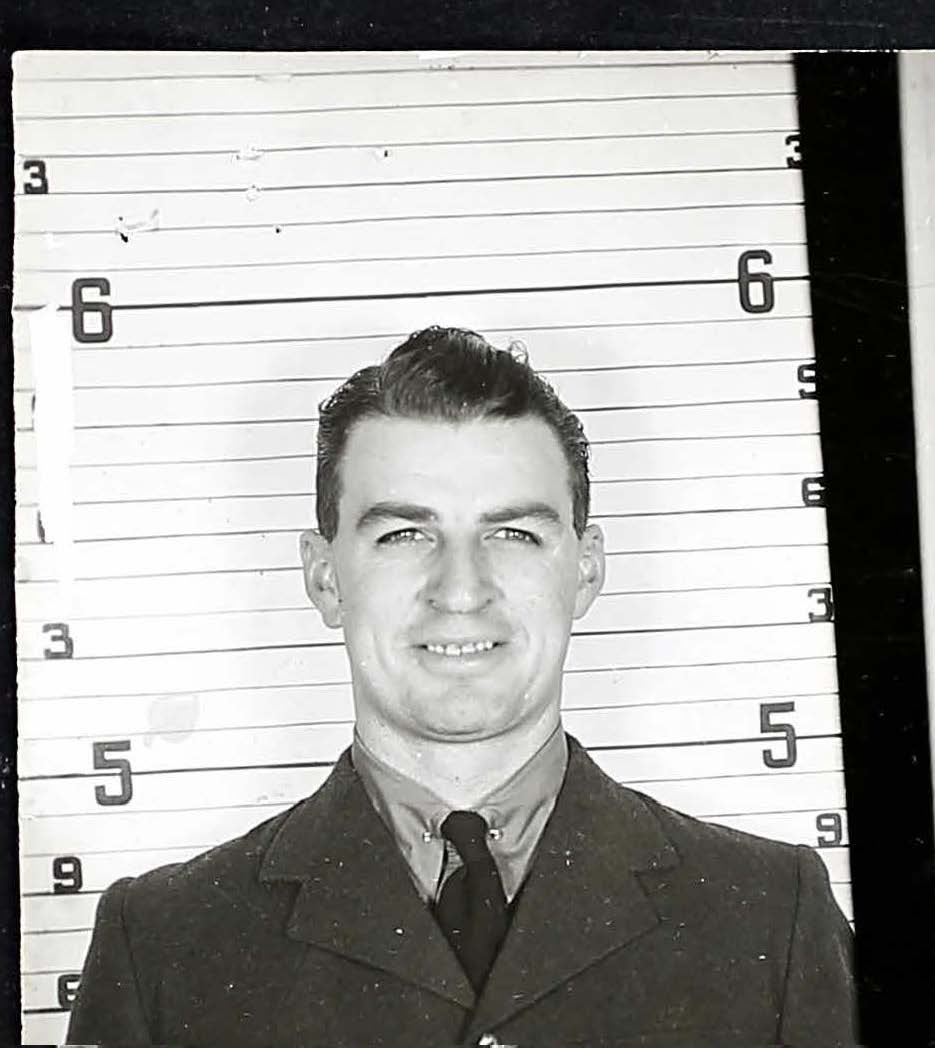

James had enlisted in the NPAM October 9, 1940, stating his preference was to serve in the Air Force. At that time, he was a service station owner. He stood 5’9” tall, had blue eyes and dark brown hair. A small wine stain on the upper medial right thigh was noted. He weighed 157 pounds. “States that breathing through left side of nose is obstructed. Was advised by nose specialist to have operation. There is a pellet in right eye from shotgun cartridge. Was not advisable to remove it. Is TB contact and is to be examined in three months. One carious tooth.”

James was a mechanic before he enlisted with the RCAF in February 1942, in Hamilton, Ontario, working at Canadian Industries Limited (CIL) for one year. “Physically fit, slightly nervous. Of good appearance, keen, alert, has the appearance of one who will do well as Pilot, willing to take DPYT School Course to qualify. Believe he will make good.” By this time, he weighed 166 pounds. He hoped to start his own business after the war. He felt that “spotting different makes of planes as they fly overhead and have a desire to be fixing or flying planes” was a special qualification useful to the RCAF. He liked hockey, baseball, lacrosse, billiards, table tennis, and bowling. He indicated he had 12 hours in a plane as a passenger.

James started his journey through the BCATP at No. 1 Manning Depot, Toronto, April 16 to June 10, 1942. He was then sent to No. 4 Manning Depot in Quebec, then No. 5 Manning Depot, Lachine until August 29, 1942.

At No. 5 ITS, Belleville, August 30 to November 31, 1942, James was 88th out of 106 with 65%. “Mature, sincere, conforms, popular with his fellows, but not the type that one would look to for leadership.”

At No. 10 EFTS, Pendleton, November 22, 1942 until February 20, 1943, James was 22nd out of 27 with 63.3%. Flying: 67.7%, 8th out of 27 in class. He was above average in cockpit drill. “A fair pilot, rather slow to learn, but should make an average pilot.”

At No. 2 SFTS, Uplands, February 21 to July 23, 1943, James was 51st out of 58 in class with 65.87%. Flying: 50th out of 59 with 71.66%. He was deemed average. “Satisfactorily progressed as a pilot to an average pass. Slightly weak on recovery from spins by reference to instruments. Appearance and bearing fair. Lacks initiative. Would not make a good officer.” He was in medical/hospital (Strathcona) isolation from March 19th to April 4, 1943.

James was taken on strength at No. 9 B&G School Mont Joli, Quebec July 24 to October 30, 1943.

James was at No. 10 BGS, Mount Pleasant, October 31, 1943 to July 10, 1944. February 16, 1944: “A high average staff pilot in all repsects. Instruments: Above average. Night: Not tested. Airmanship: High average. General knowledge: Average. This pilot did a very good test. His instrument flying was above average including an instrument take-off.” April 20, 1944: “Steady type NOC. Good worker. Needs to improve general knowledge. Recommend to rank of Temporary Flight Sergeant.” July 11, 1944: An above the average NCO and pilot. Should be an asset to any station.”

On July 11 1944, James was posted to No. 8 O.T.U., Greenwood, Nova Scotia. Here he became known as ‘Walt.’

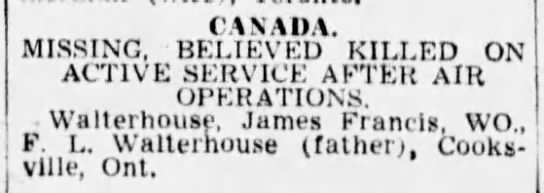

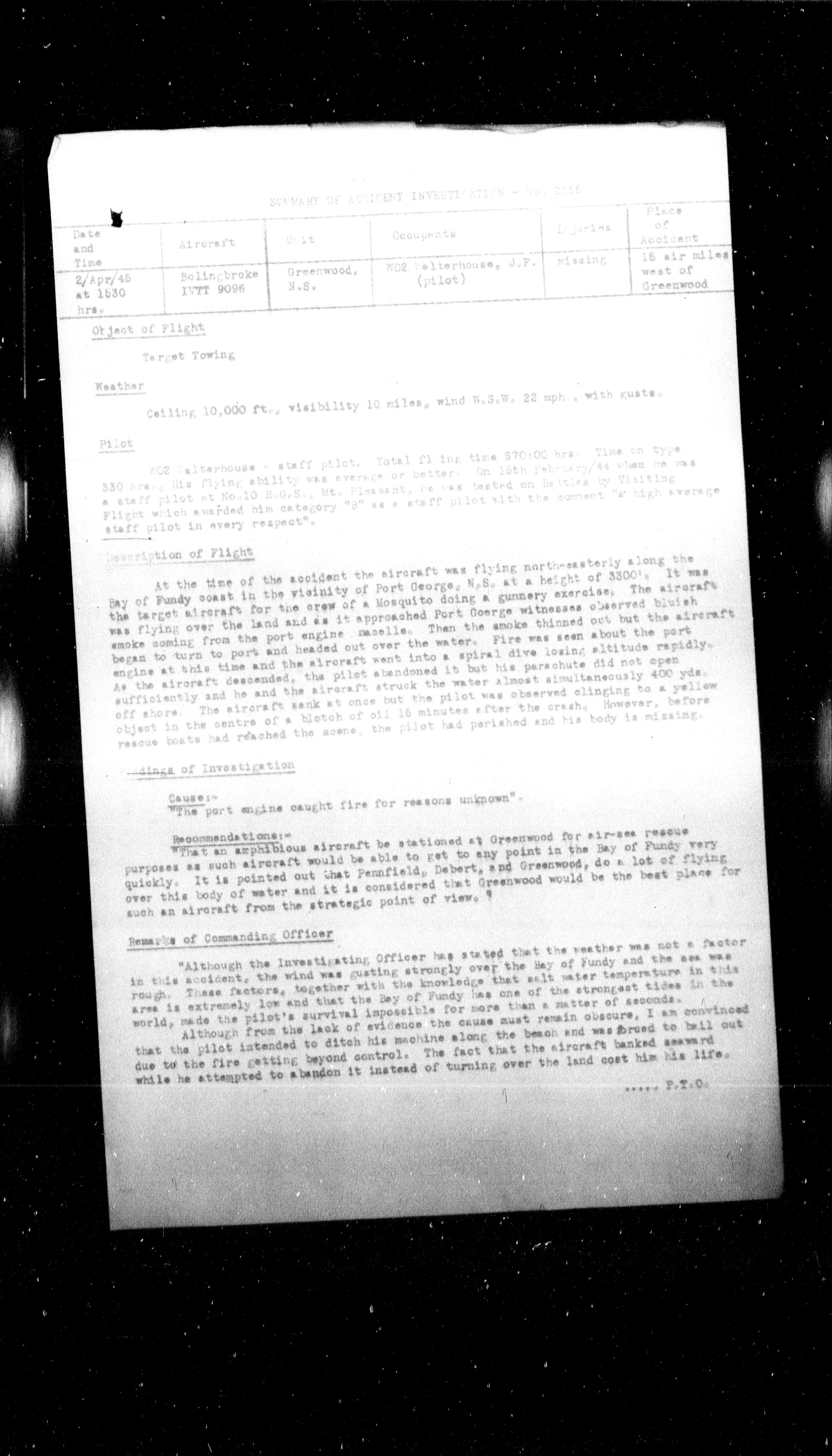

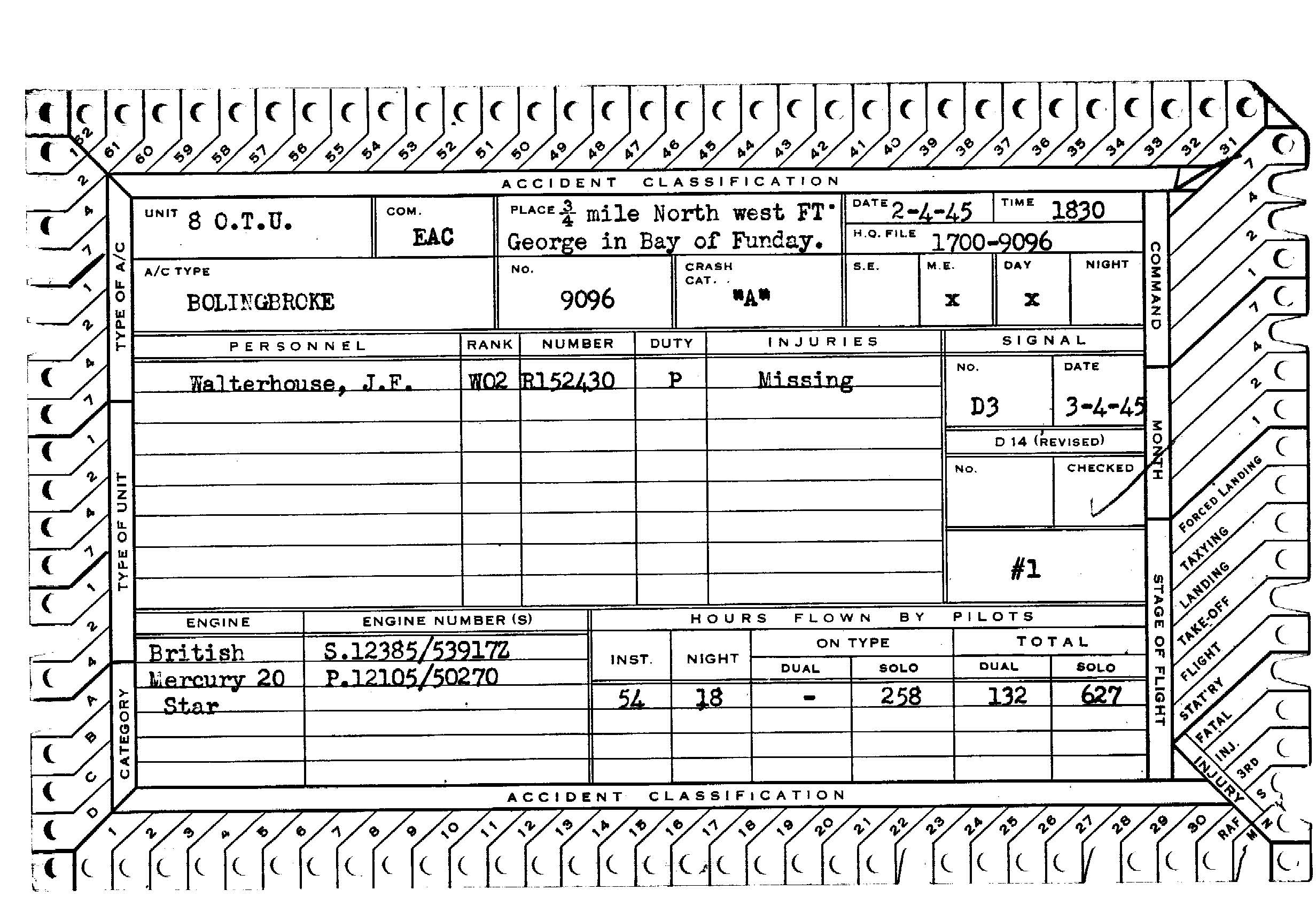

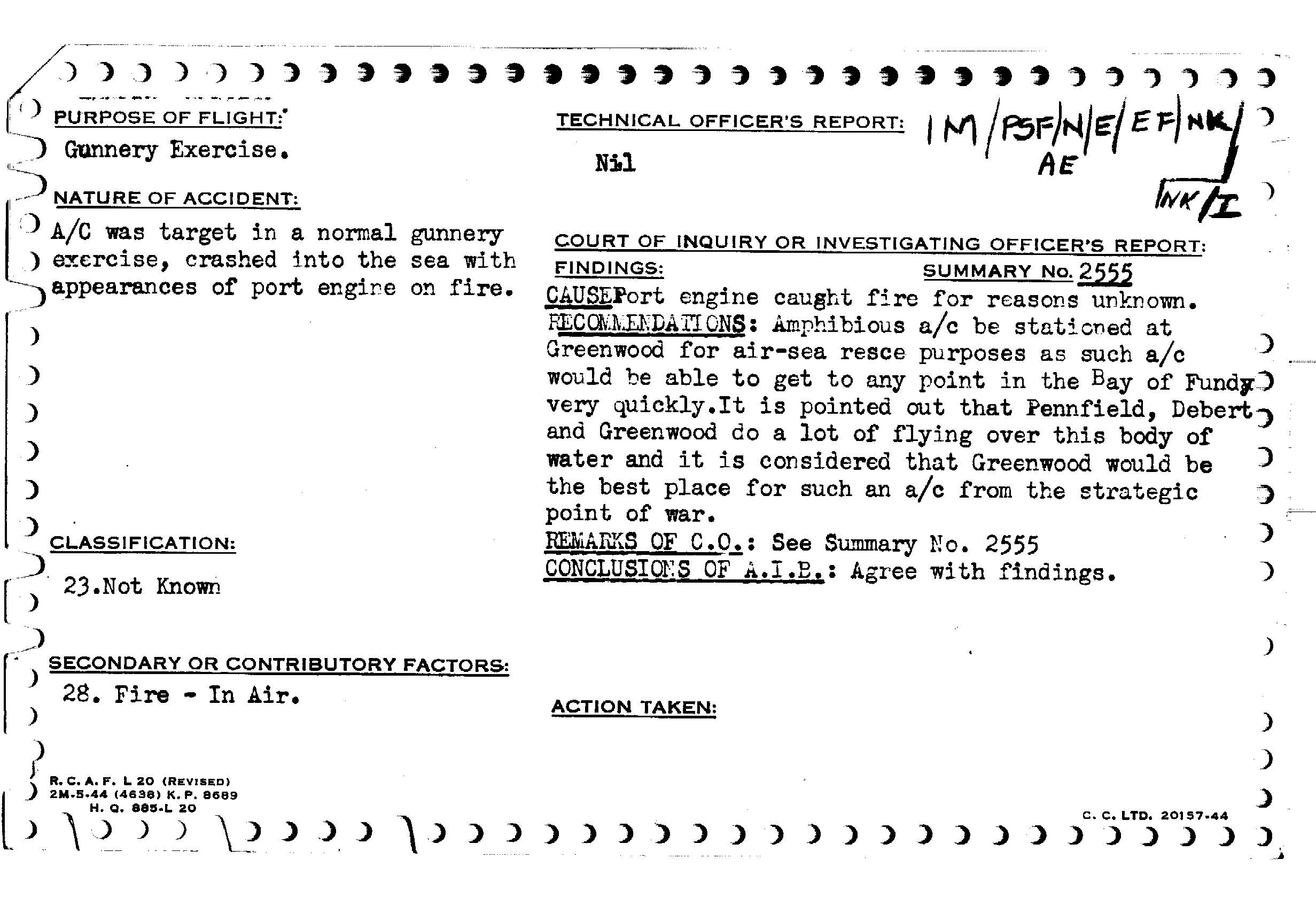

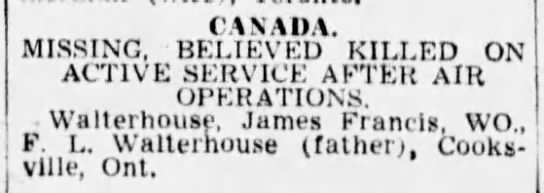

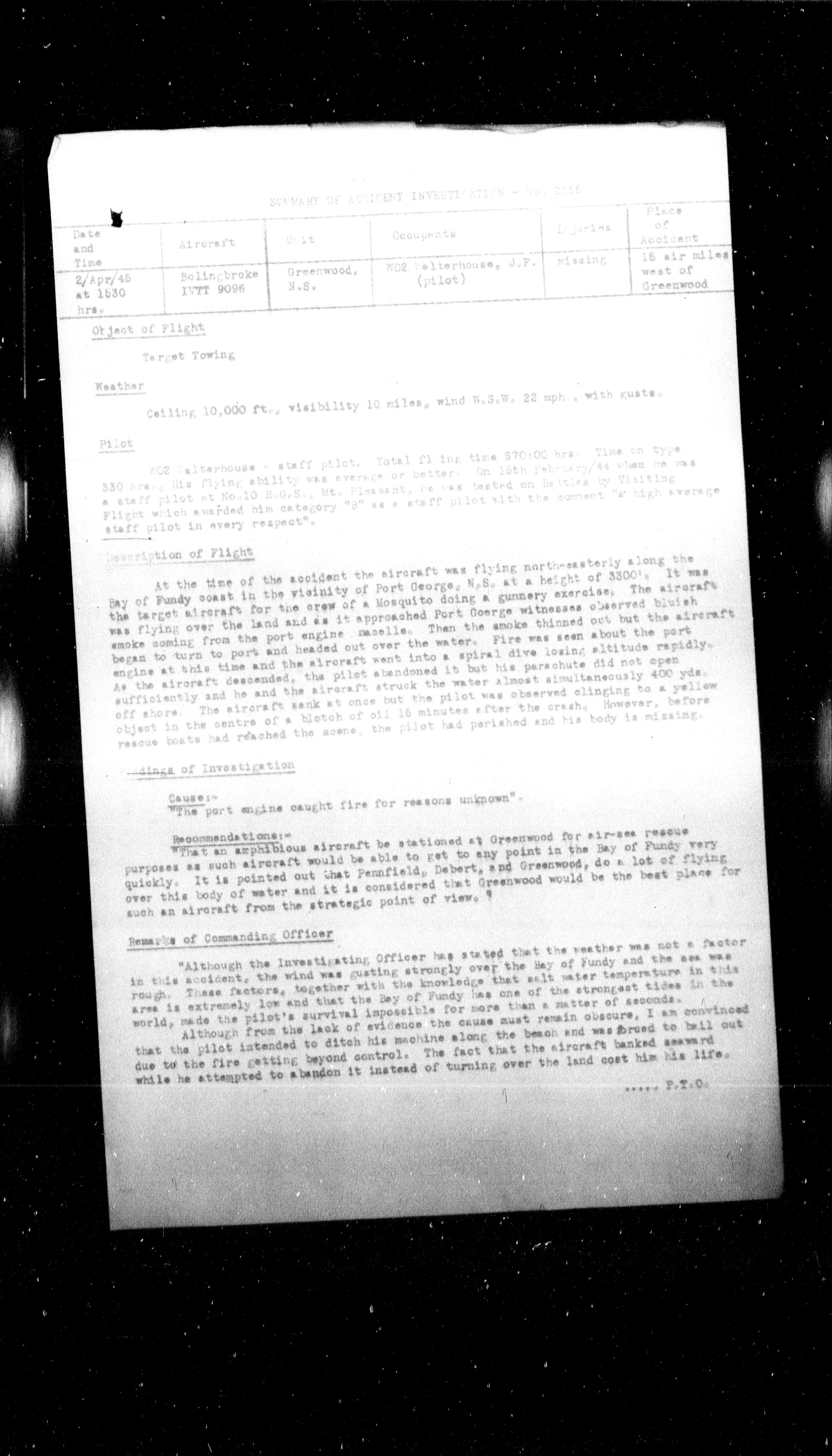

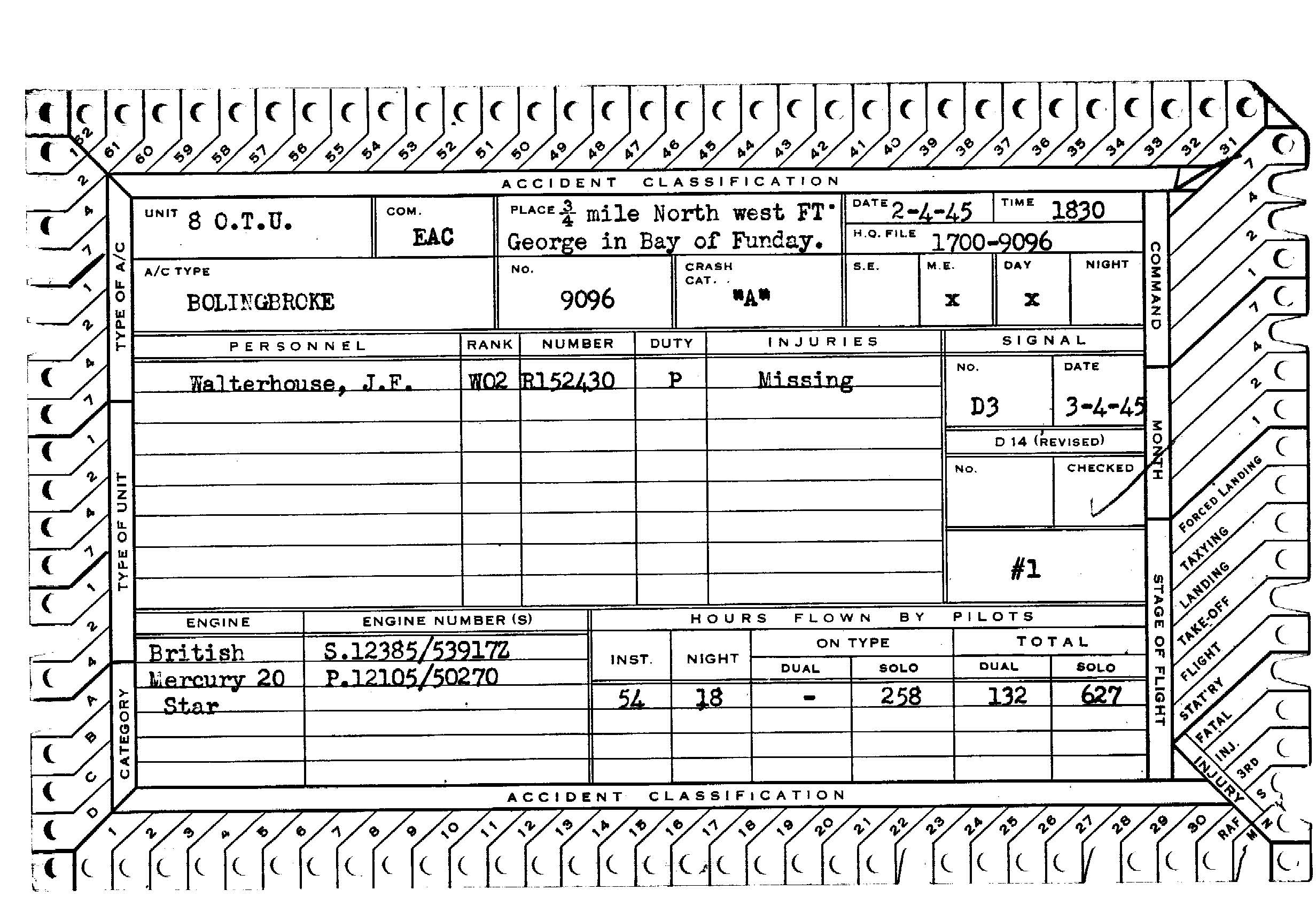

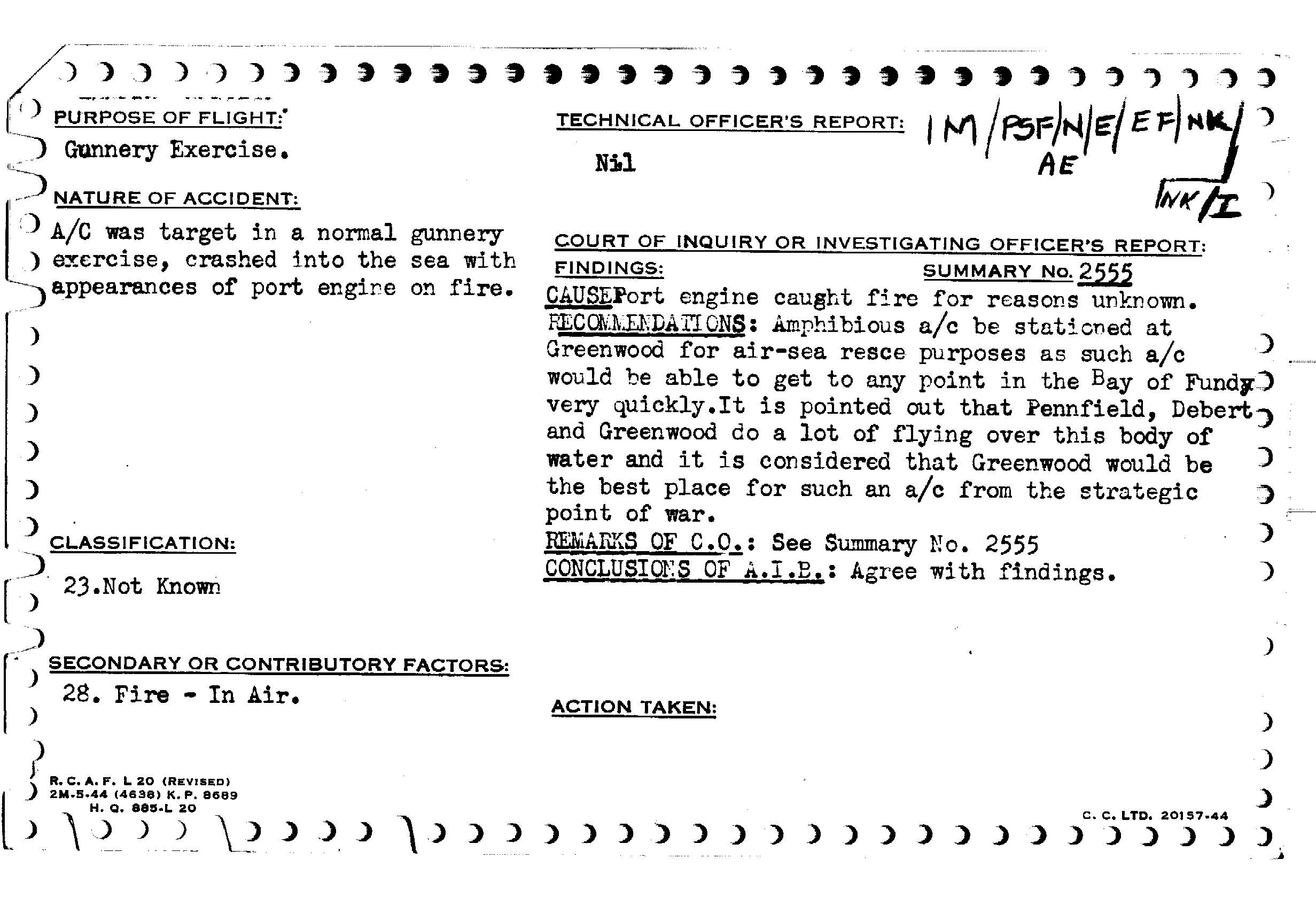

Flying Bolingbroke 9096 he was lost. The plane crashed into the sea at approximately 1530 hours, April 2, 1945, off Port George, Annapolis County, NS. Full Court of Inquiry can be found on microfiche T12353, image 4963. The crash card stated: “A/C was target in a normal gunnery exercise, crashed into the sea with appearances of port engine on fire. CAUSE: Port engine caught fire for reasons unknown. RECOMMENDATIONS: Amphibious a/c to be stationed at Greenwood for air-sea rescue purposes as such a/c would be able to get to any point in the Bay of Fundy very quickly. It is pointed out that Pennfield, Debert and Greenwood do a lot of flying over this body of water and it is considered that Greenwood would be the best place for such an a/c from the strategic point of war.” It also showed that the plane crashed ¾ mile northwest of Port George in the Bay of Fundy, about 15 air miles west of Greenwood.

PILOT: WO2 Walterhouse, staff pilot. Total flying time: 570 hours. Time on type: 330 hours. His flying ability was average or better. On 16th of February 1944 when he was a staff pilot at #10 Bombing Gunnery School Mount Pleasant, he had tested on Battle by visiting flight which was awarded his category ‘B’ as a staff pilot with the comments ‘a high average staff pilot in every respect.’

DESCRIPTION OF THE FLIGHT: at the time of the accident, the aircraft was flying north easterly along the Bay of Fundy coast in the vicinity of Port George, Nova Scotia at a height of 3300 feet. It was the target aircraft for the crew of a mosquito doing a gunnery exercise. The aircraft was flying over the land and as it approached port George, witnesses observed blueish smoke coming from the port engine nacelle. Then the smoke thinned out but the aircraft began to turn to port and headed out over the water. Fire was seen about the port engine at this time and the aircraft went into a spiral dive losing altitude rapidly. As the aircraft descended, the pilot abandoned it, but his parachute did not open sufficiently and he and the aircraft struck the water almost simultaneously 400 yards offshore. The aircraft sank at once, but the pilot was observed clinging to a yellow object in the centre of a blotch of oil 15 minutes to the crash. However, before rescue boats had reached the scene, the pilot had perished and his body is missing.

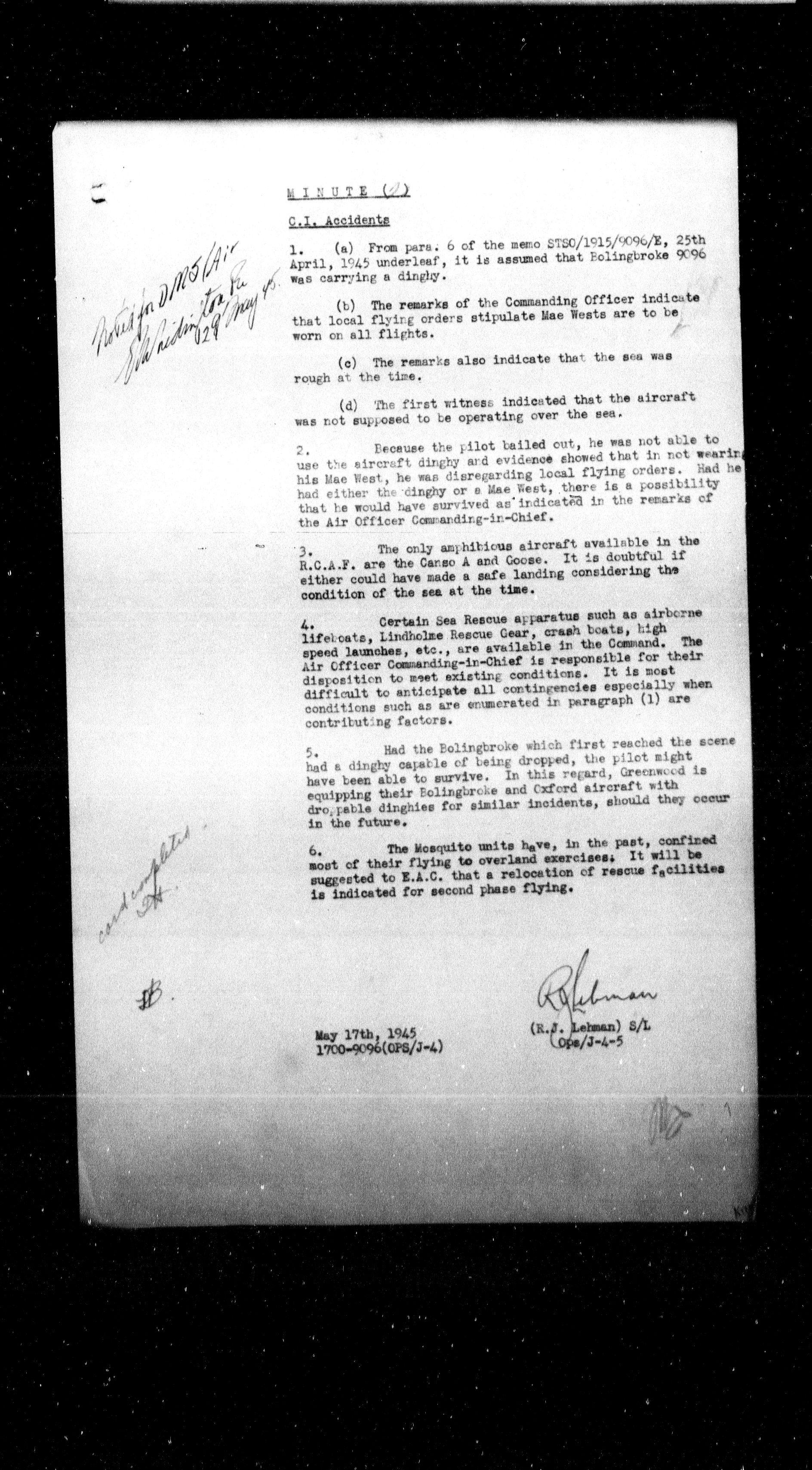

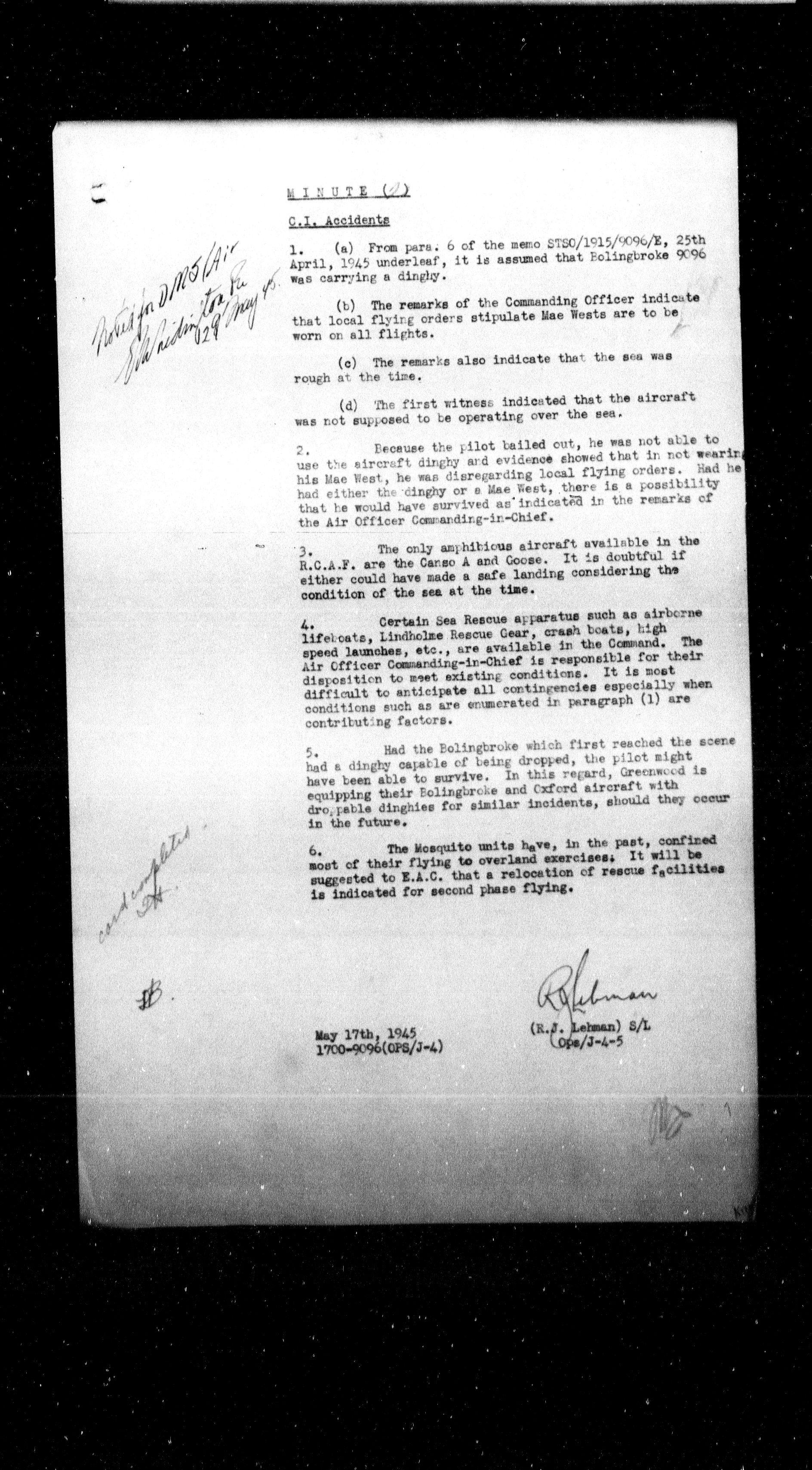

From a memo from the CI, Accidents: it is assumed that Bolingbroke 9096 was carrying a dinghy. The remarks of a commanding officer indicate that local flying orders stipulate Mae Wests are to be worn on all flights. The remarks also indicate that the sea was rough at the time. The first witness indicated that the aircraft was not supposed to be operating over the sea. Because the pilot bailed out, he was not able to use the aircraft dinghy and evidenced showed that in not wearing his Mae West, he was disregarding local flying orders. Had he had either the dinghy or the Mae West, there is a possibility that he would have survived as indicated in the remarks of the Air Officer Commanding in Chief. The only amphibious aircraft available in the RCAF are the Canso A and Goose. It is doubtful if either could have made a safe landing considering the condition of the sea at the time. It is most difficult to anticipate all contingencies especially when conditions such as are enumerated are contributing factors. Had the Bolingbrook which first reached the scene had a dinghy capable of being dropped, that pilot might have been able to survive. In this regard, Greenwood is equipping their bowling broken Oxford aircraft with droppable dinghies for similar incidents, should they occur in the future. The mosquito units have, in the past, confined most of their flying to over land exercises. It will be suggested to E.A.C. that a relocation of rescue facilities is indicated for second phase flying.”

In a memo from G/C Wilkis, CI Accidents: “The question of location of air to sea rescue equipment is a matter for your consideration. The Bay of Fundy is a very busy area and although the Mosquito O.T.U.s are due to close shortly, their place will be taken by other units on the same airfields. The Bay of Fundy is notorious for its cold water and fast running tides, so that any aircraft that fall into the sea, unless they can get into a dinghy, have very little chance of survival. In the accident in question, it appears probable that the pilot was afloat for 15 minutes after the crash which does not give much margin for delay if he is to be rescued.”

On April 4, 1945, G/C E. M. Reyno, CO of RCAF Station, Greenwood, NS wrote to Mr. Walterhouse. [See documents above for full letter.]. “Your son was detailed for a normal, training cooperation flight in a Bolingbrook twin engine aircraft and he was to fly along the Bay of Fundy coast at a height of from 3000 to 5000 feet. He was cooperating with another machine at the time, which was above him and about three miles to one side, when the accident occurred. Your son was alone in his aircraft at the time. His machine, for some reason as yet undiscovered, apparently developed some form of technical failure and it started to lose height. When at a fairly low altitude, some distance over the water, your son bailed out and was seen to land in the waters of the Bay. As fate would have it, there was a very heavy sea running due to a strong gusty wind and an ebbing tide and he disappeared from view. The wet shroud lines and the wind filled canopy of his parachute, together with the well-known strength of the Bay of Fundy tide, made his survival impossible for more than a few minutes. A boat immediately put out from a village along the shore, but when it reached the scene, all that was found was bits of scattered wreckage from the machine. Two long range aircraft, one a flying boat, were immediately dispatched to the scene, with complete rescue equipment, including an airborne life raft, but no trace of his body has been found in spite of the most exhaustive efforts. Further, several units of the Royal Canadian Navy, along with many other local water craft, were immediately dispatched to the scene an covered the entire area thoroughly, all day and night, without success. under these circumstances, I know you will understand when I tell you that we have very little hope of your son’s life having been spared, but of course, all our aircraft, as well as local naval units have been warned to maintain a constant watch along the entire coast. I feel that I need hardly to tell you that there were many others here on the Station, together with the host of friends your son leaves behind in the service, sharing your sorrow this day because Walt, as we knew him, was one of the most popular pilots ever to be based at Greenwood. His cheerful disposition and constant smile won him many friends and instances of his outstanding ability and adaptability to flying were well known to us all. As a result of this tragic and untimely accident, the service has suffered a severe loss, but it has gained in the splendid example he set his fellow airmen.”

Mr. Walterhouse wrote on April 21, 1945 to the Benevolent Fund: “Received your kind letter of April 11 in regard to the death of my son, James. I do not need any financial assistance, all I hope is the RCAF will do all in their power to locate his body and ship to Cooksville. Thanking you for your kind letter.”

On April 25, 1945, a memo by S/L W. B. Cooper: “WOII Walterhouse was assessed as an average pilot. He was flying over land at the time his aircraft caught fire and turned out to see, and in my opinion reading over the evidence this was deliberate. I feel that he bailed out intending to land on the fairly wide beach in an effort to save himself a rough landing in large trees. Unfortunately, he misjudged his distance and landed about 400 yards off shore. I feel certain that if he had been wearing his Mae West at the time, he would have made shore. It is true that the water in the Bay of Fundy is cold to the extreme and that the tide is very strong, but I still think that any normal man that could swim, plus with the aid of a Mae West, could have literally fought his way to shore. As there is no evidence to determine the cause of the fire or the condition of the aircraft at the time the pilot bailed out, it is impossible to say whether the pilot was guilty of an error of judgment or that the aircraft was out of control. The Hudson carrying the boat arrived at the scene approximately 40 minutes after the pilot bailed out. While 40 minutes was an exceptionally good show on the part of the crew of the aircraft, 40 minutes is far too long for a man to stay in the Bay of Fundy, winter or summer. The same applies to the Canso sent from Yarmouth. It arrived after the Hudson, being a slower aircraft. It is felt, therefore, that some means of rapid air sea rescue be stationed at Greenwood to be maintained and kept in immediate readiness at all times when any flying is in progress in the Bay of Fundy area. I also wish to point out the fact that the dinghy in a Bolingbrook is stowed in the rear of the port engine nacelle. The dinghy was undoubtedly rendered useless by the fire in this engine. This point was not brought out in the investigation.”

In a letter to Mrs. Walterhouse is 1955, by which time she had passed away, the family was informed that since James had no known grave, his name would appear on the Ottawa Memorial.