July 14, 1915 - September 29, 1944

Gordon Paterson, Jr., born in Duluth, Minnesota, was the son of Gordon Paterson, manager, and Elizabeth “Bessie” (nee Currie) Paterson. Their address was noted as Toronto. His father was from Kingston, Ontario and his mother was born in St. Paul, Minnesota. He had one younger brother, Stuart Falconer Paterson. The family was Presbyterian. Gordon lives in Minnesota for seven years, New York for thirteen years, and Ontario for nine years.

Gordon had attended Upper Canada College in 1933-1936, then Queen’s University from 1936-1938, taking general studies. He was an insurance salesman. He liked hunting, shooting, boxing, and football.

Gordon had a son, Gordon Patterson III, born in October 1935 in New York City, “child of first marriage” and was in the child’s mother’s custody. Helen Paterson asked for an annulment in January 1940 in Queens, New York. She claimed “abandonment of the plaintiff by the defendant and because the defendant failed and refused to support the plaintiff.” Gordon was told to pay $25 per month for support of his son. She remarried and became Helen Rothmayer. Gordon married Mary Hazel McCauley on May 10, 1941. They divorced by March 1944, Mary claiming Gordon committed adultery. Gordon was to pay the costs of the divorce.

He stood 6’2” and weighed 208 pounds. He had blue eyes and brown hair. A scar on the centre of his forehead was noted. His septum was removed from his nose at some time before enlisting with the RCAF in Toronto, Ontario on September 11, 1942. “Observer only. Big, powerful build. Alert, intelligent, good personality, superior type. Excellent appearance, tall, hefty. Very good attitude. Feels his turn has come, always wanted to fly. Appears promising material. Good aircrew material.”

He started his journey through the BCATP at No. 1 Manning Depot Toronto, on November 20, 1942, until January 24, 1943. He went to Pre-Aircrew Education, University of Toronto January 25 to March 20, 1943. From there, he was sent to No. 20 EFTS, Oshawa, Ontario from March 21-April 25, 1943. In April 1943: “Age 27 years. Married. Wife keen. Choice: Pilot, Navigator. Tarmac No. 20 EFTS: Never flew; flew as passenger, five hours prior to enlistment. Never read any books on aviation. Rather an aggressive, argumentative type who will probably get under his instructor’s skin. Very filled with self-importance, seems very keen to be a pilot. Doubt if he makes the grade.”

He returned to No. 1 Manning Depot April 26, 1943 until May 15, 1943. He began pilot training at No. 1 ITS, Toronto May 16 until August 7, 1943. He went to No. 23 EFTS, Davidson, Saskatchewan, August 8 until October 16, 1943. His next posting was at No. 1 SFTS, Camp Borden from October 17, 1943, until March 24, 1944. He traveled to Saguenay, Quebec and No. 1 O.T.U., March 25, 1944. He was then sent to Western Air Command, Vancouver, BC, August 12, 1944, and three days later was taken on strength with 133 Squadron, Patricia Bay, BC.

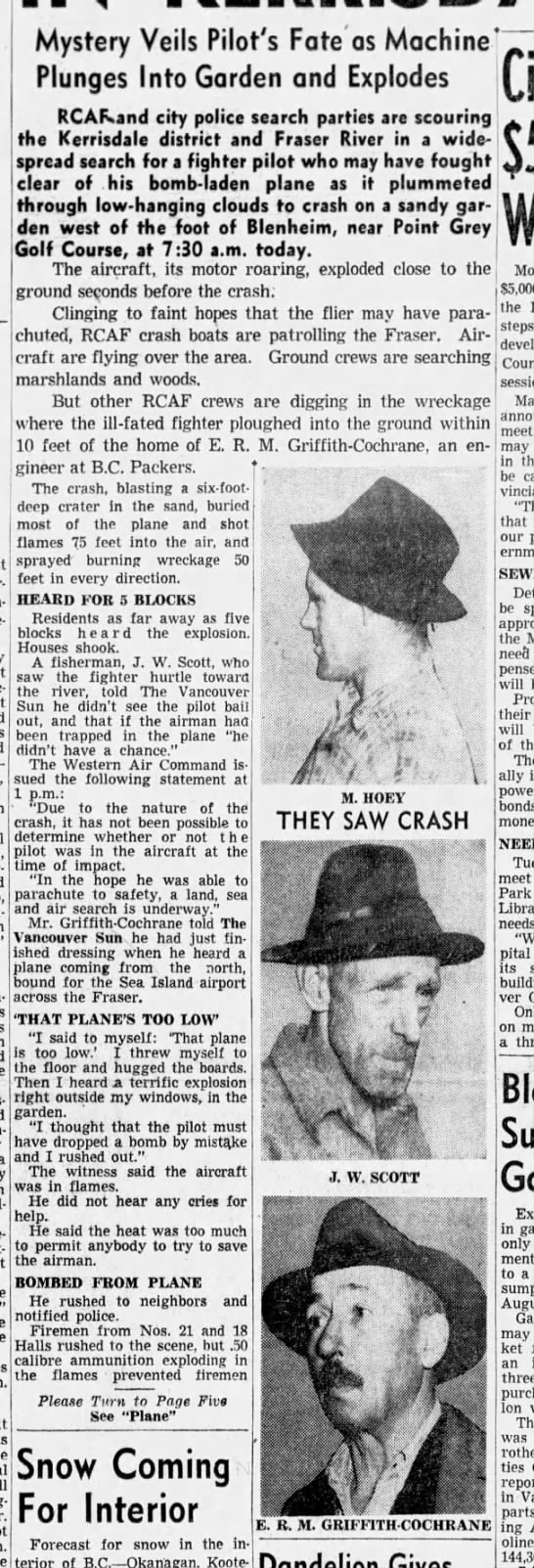

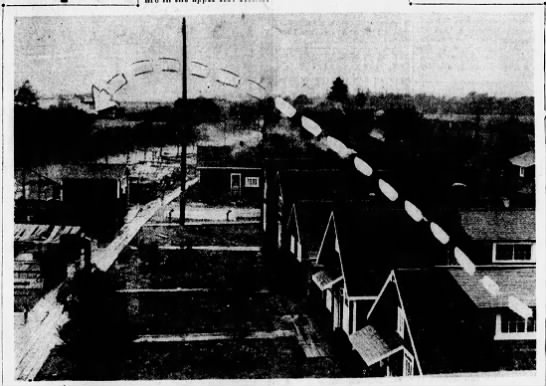

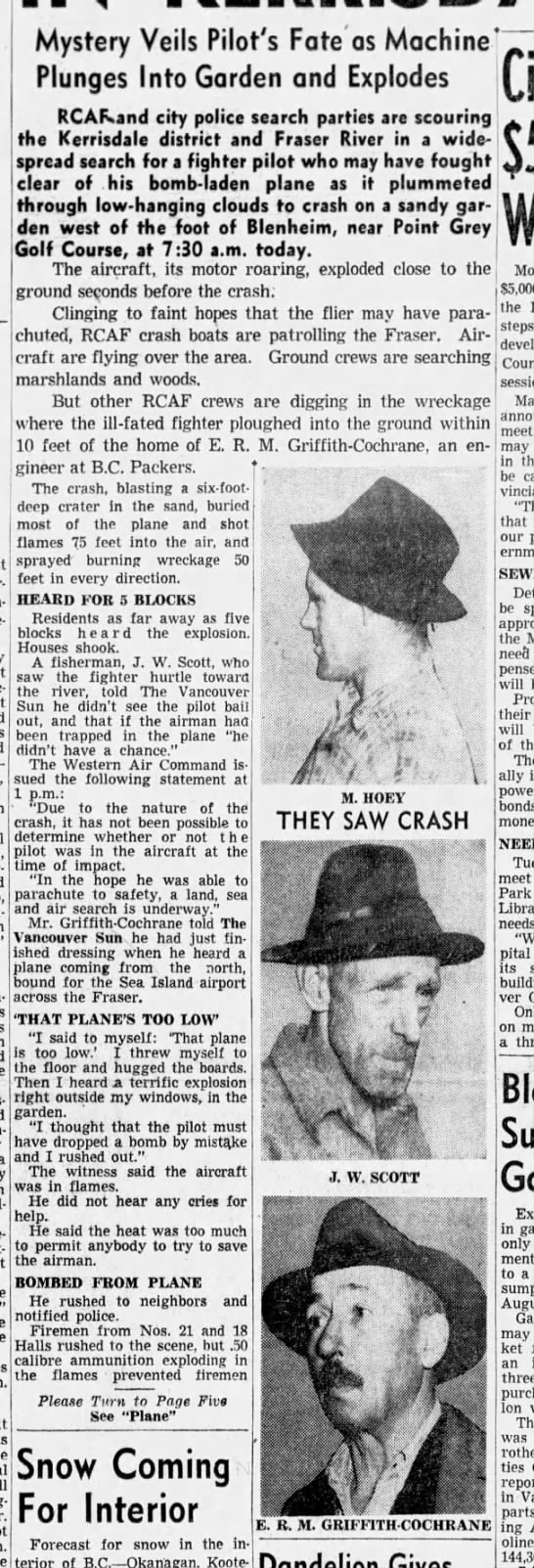

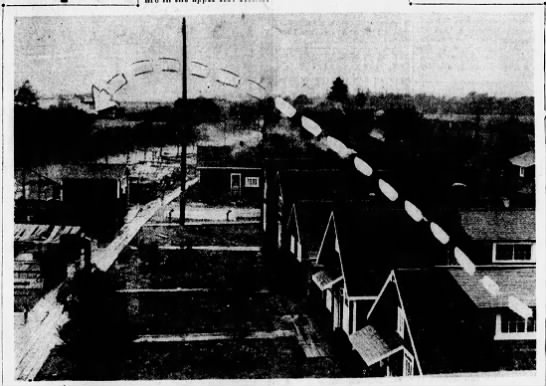

“Presumed killed in flying accident, dawn patrol over northwest outskirts of city.” Six miles east of Discovery Island, two miles north of Sea Island aerodrome. Time: 0740 hours. The accident made Vancouver newspapers, with eyewitness accounts.

Accident at 0740 hours, September 29, 1944, on an unnamed island in North Arm of Fraser River at the foot of Blenheim Street, Vancouver, BC at a point approximately two miles north of the Sea Island Aerodrome. “On dawn patrol, pilot became separated from his leader in very bad visibility. Sector Control and leader’s last R. T. contact with pilot and aircraft crashed a few minutes later but pilot is missing. Aircraft was obviously out of control but whether this occurred while pilot was in cockpit or after he bailed out is unknown. The circumstances of this accident be related to fighter pilots in this command, and the absolute necessity of a No. 2 man flying close to his leader at all times during poor visibility be emphasized.”

The Court of Inquiry called fifteen witnesses. For full inquiry, please see link below.

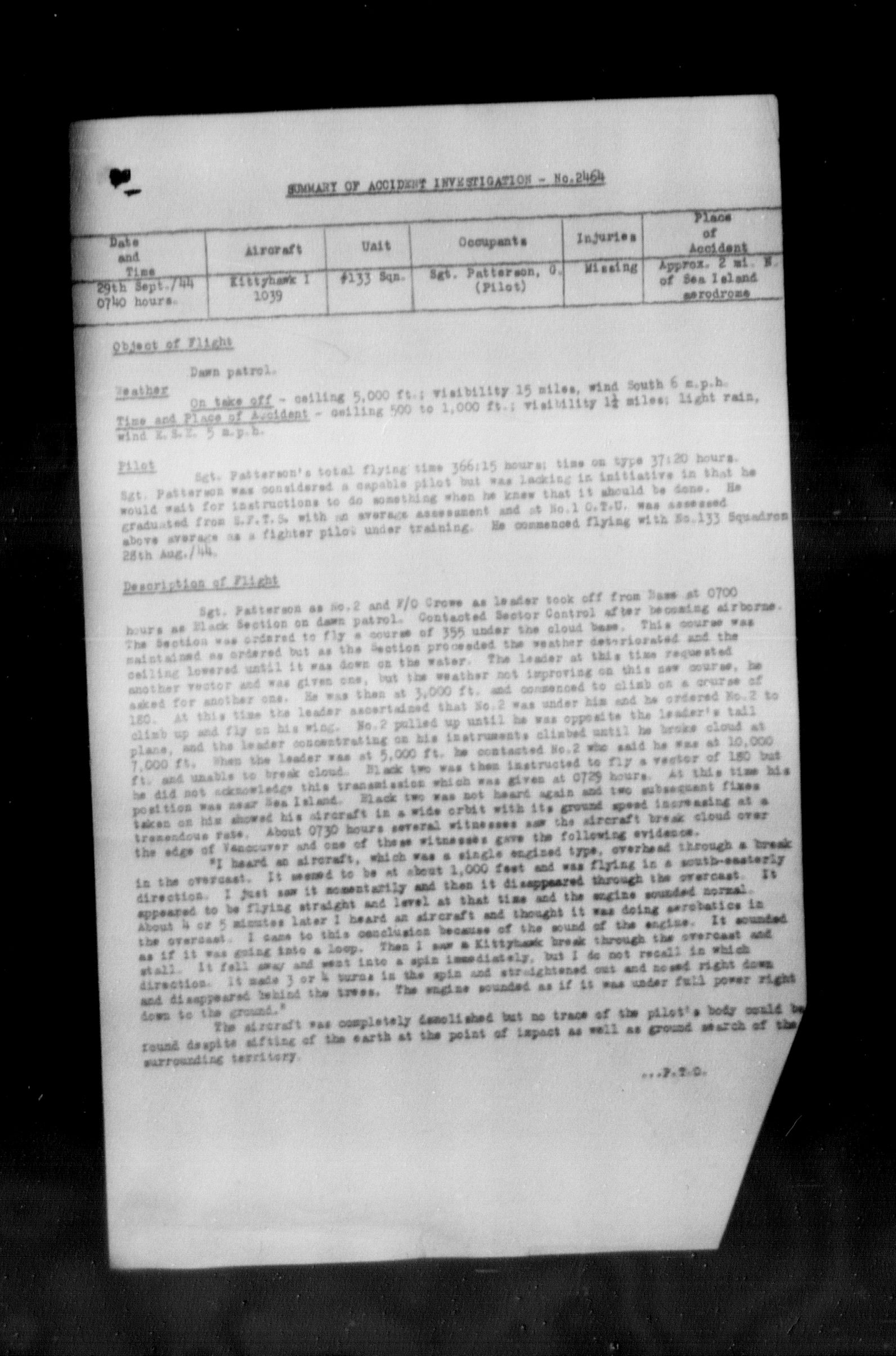

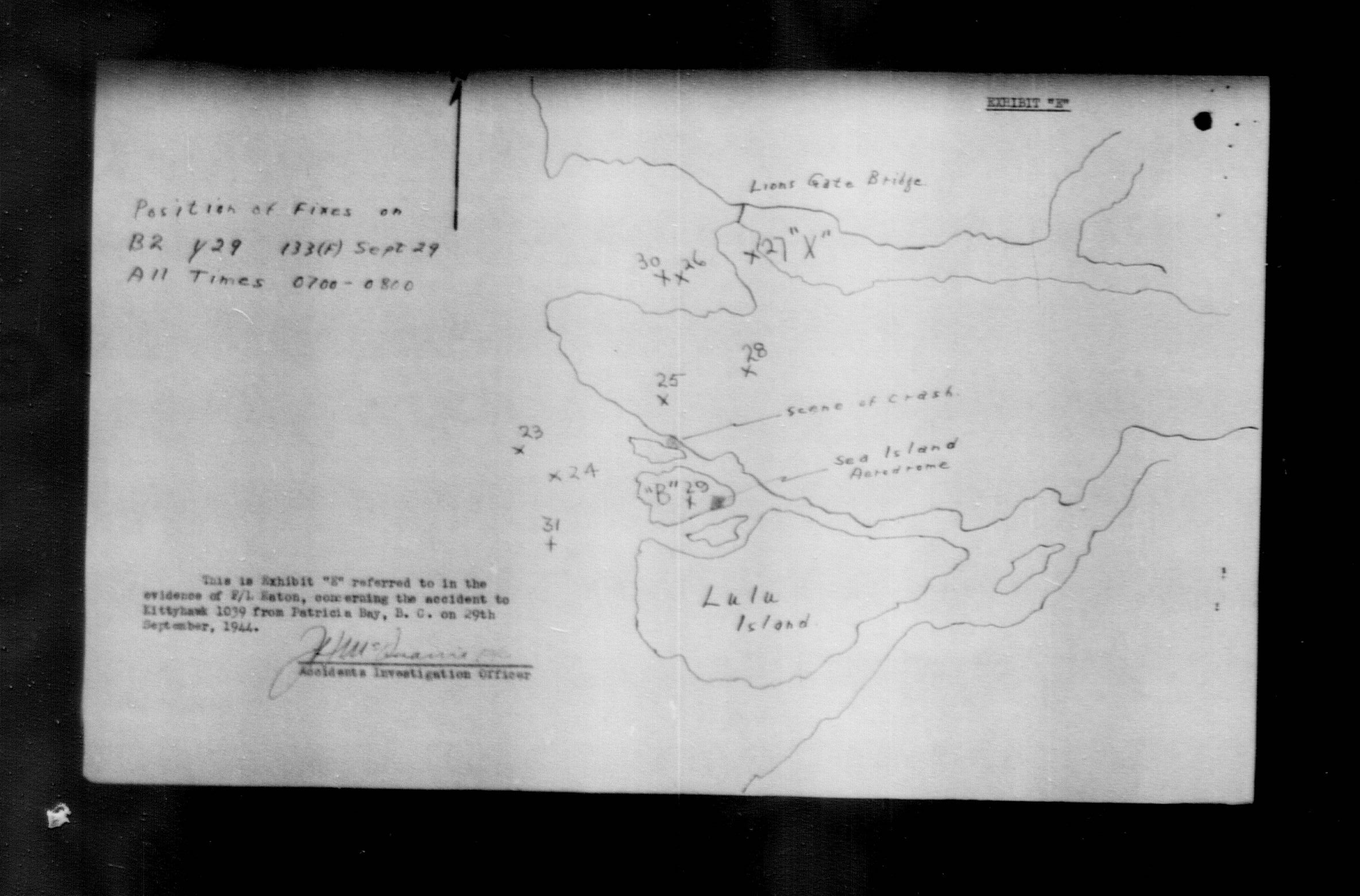

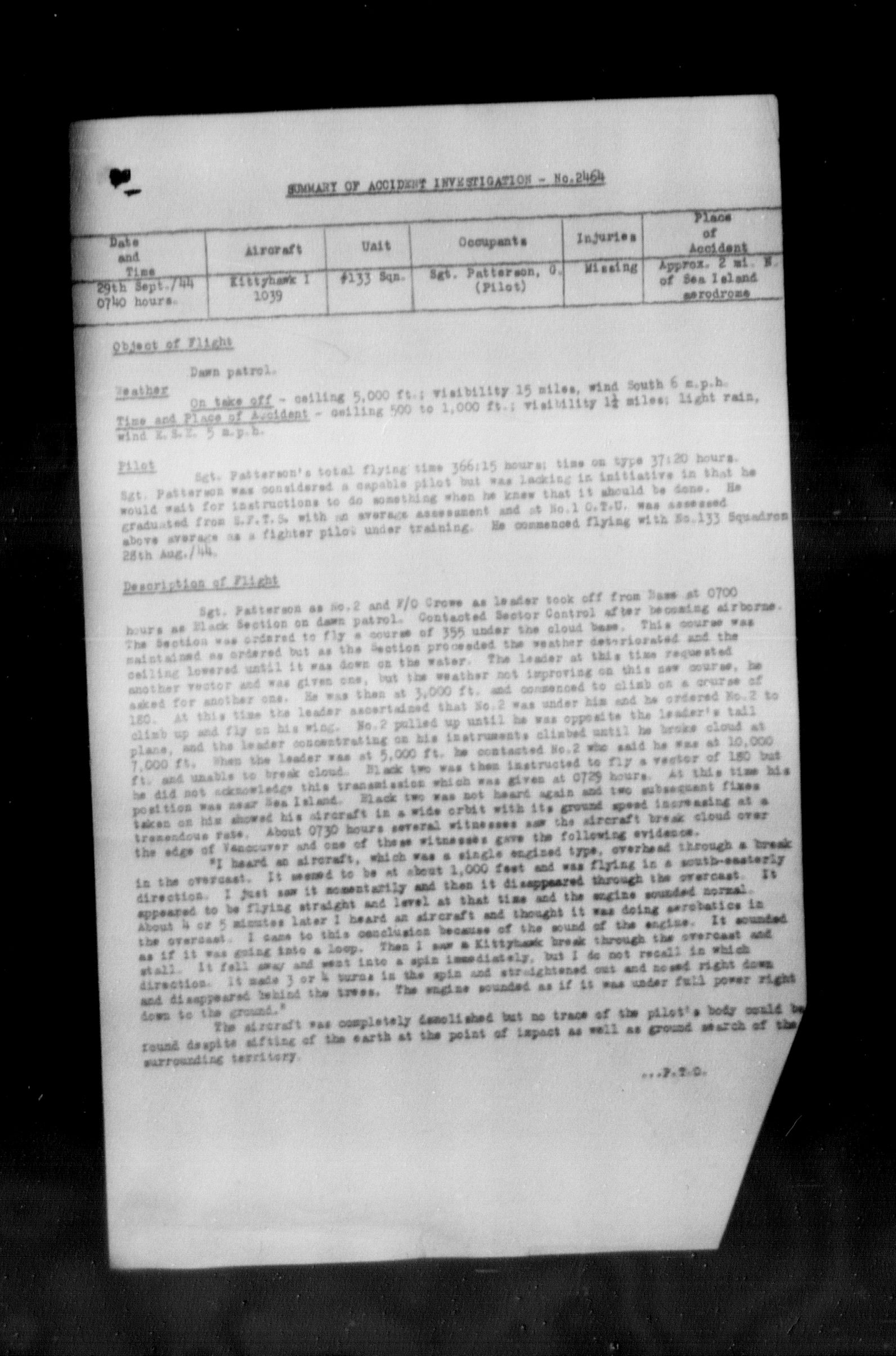

OBJECT OF FLIGHT: Dawn Patrol on order of F/C Wann. No special instructions were given prior to this flight which was routine. One occupant was not instructing other. WEATHER: On take-off: ceiling 5,000 feet, visibility 15 miles, wind south at 6 mph. TIME AND PLACE OF ACCIDENT: ceiling 500 to 1000 feet, visibility 1 ½ miles, light rain, wind ESE, 5 mph. PILOT: Sgt. Paterson’s total flying time 366:15 hours; Time on this type 37:20 hours. Sergeant Paterson was considered a capable pilot but was lacking initiative in that he would wait for instructions to do something when he knew that it should be done. He graduated from EFTS with an average assessment an at No. 1 O.T.U. was assessed above average as fighter pilot under training. He commenced flying at 133 Squadron August 28th, 1944. DESCRIPTION OF FLIGHT: Sgt. Paterson as No. 2 and F/O Crowe as leader took off from base at 0700 hours as Black Section on dawn patrol. Contacted sector control after becoming airborne. The section was ordered to fly a course of 355 under the cloud base. This course was maintained as ordered but as the section proceeded, the weather deteriorated, and the ceiling lowered until it was down on the water. The leader of this time requested another vector and was given one, but the weather was not improving on this new course, he asked for another one. He was then at 3000 feet and commenced to climb on a course of 180. At this time the leader ascertained that No. 2 was under him and he ordered No. 2 to climb up and fly on his wing. No. 2 pulled up until he was opposite the leader’s tailplane, and the leader concentrating on his instruments, climbed until he broke cloud at 7000 feet. When the leader was at 5000 feet, he contacted No. 2 who said he was at 10,000 feet and unable to break cloud. Black 2 was then instructed to fly a vector of 180 but he did not acknowledge this transmission which was given at 0729 hours. At this time, his position was near Sea Island. Black 2 was not heard again and two subsequent fixes taken on him showed his aircraft in a wide orbit with its ground speed increasing at a tremendous rate. At about 0730 hours, several witnesses saw the aircraft break cloud over the edge of Vancouver and one of these witnesses gave the following evidence: ‘I heard an aircraft, which was a single engine type, overhead through a break in the overcast. It seemed to be at about 1000 feet and flying in and southeasterly direction. I just saw it momentarily and then it disappeared through the overcast. It appeared to be flying straight and level at that time and the engine sounded normal. About four or five minutes later, I heard an aircraft and thought it was doing aerobatics in the overcast. I came to this conclusion because of the sound of the engine. It sounded as if it was going into a loop. Then I saw a Kittyhawk break through the overcast and stall. It fell away and went into a spin immediately, but I do not recall in which direction. It made three or four turns in a spin and straightened out and nosed right down and disappeared behind the trees. The engine sounded as if it was under full power right down to the ground.” The aircraft was completely demolished but no trace of the pilot’s body could be found despite sifting of the earth at the point of impact as well as ground search of the surrounding territory.

The first witness, F/L T. W. Wann, J13348, Flight Commander B Flight, stated that Sgt. Paterson came to “this squadron from Bagotville and soloed here on Kittyhawk early in September. He was a capable flyer, and his airmanship was average, but he had a tendency to wait for instructions rather than take the action which he knew to be the correct one. When Sergeant Paterson arrived at this squadron, he was first checked out in a Harvard and then did about four hours in the Harvard. At the end of that time, I flew with him on a check flight in the Harvard. In the meantime, he was given about four hours’ cockpit drill in the Kittyhawk and written gen. on the Kittyhawk aircraft and aircraft staff instructions, formation flying orders etc.”

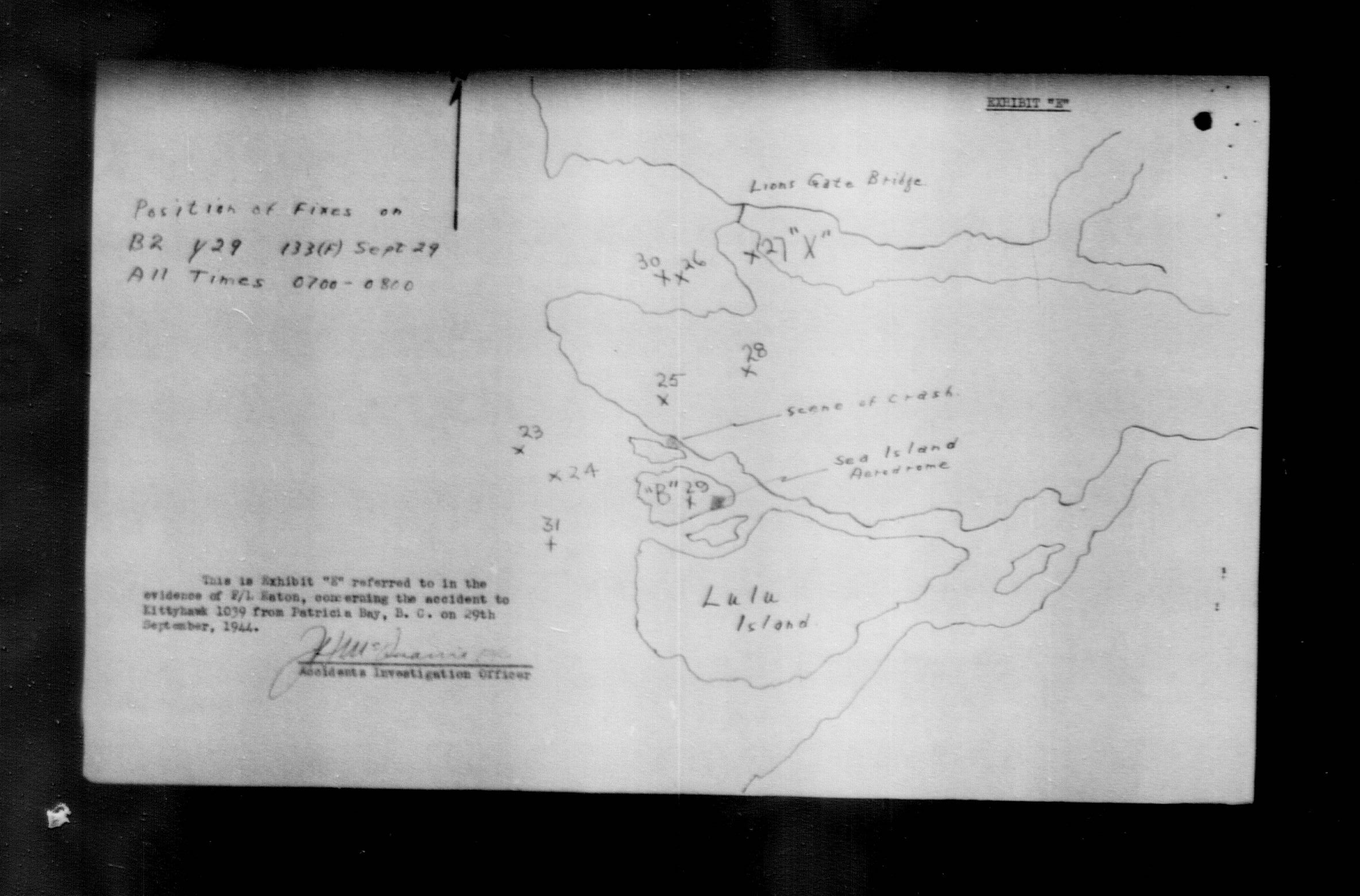

The third witness, F/L G. H. Eaton, C13860, Flight Controller, stated, “All pilots are briefed when in trouble to give a mayday call on the fixer frequency channel; sector had no knowledge that Black 2 was in trouble until R/T contact failed, and his fixes no longer came through the triangulation room. As is customary in such cases, sector continued calling Black 2 and giving him instructions should he be able to receive and not send. It was later learned that he had crashed.”

The fourth witness, who was quoted above, F/L Douglas Ward, OC Aircraft Repair Section, No. 3 Repair Depot, Vancouver, BC, also stated that “I was standing less than ¼ mile from where it crashed. I particularly watched the sky for about 5 minutes to see if the pilot bailed out, but I saw nothing. There was no trail of smoke form the aircraft of any sign of fire.”

The fifth witness, Mrs. S. Brynjolfson, living at 7225 Blenheim Street, Vancouver, stated that she did not see anything fall from the aircraft, nor see any fire in the aircraft. She was standing 300 – 400 yards from where the plane crashed.

The sixth witness, Agnes Ouellette, cannery worker, living at the foot of Blenheim Street said she saw black smoke coming from the aircraft, which was on fire, coming from the front of the aircraft, streaming back. “It seemed to be in a steep dive.”

The seventh witness, Roy Iverson, student, stated that as he was delivering newspapers, “the aircraft was flying towards me when I first saw it and it was coming from the south and a little bit east. It went into a spin to the left. I thought it would crash and I watched to see if the pilot bailed out but he didn't. The aircraft disappeared behind some trees and I heard it crash two or three seconds later. Just before it hit, I heard the roar of the engines increase. When I last saw the aircraft, it was still in a dive and was spinning to the left; it was not coming straight down but at a very steep angle. At the time of the accident, it was raining lightly and the sky was overcast but the clouds were not down very low. I could see several miles.”

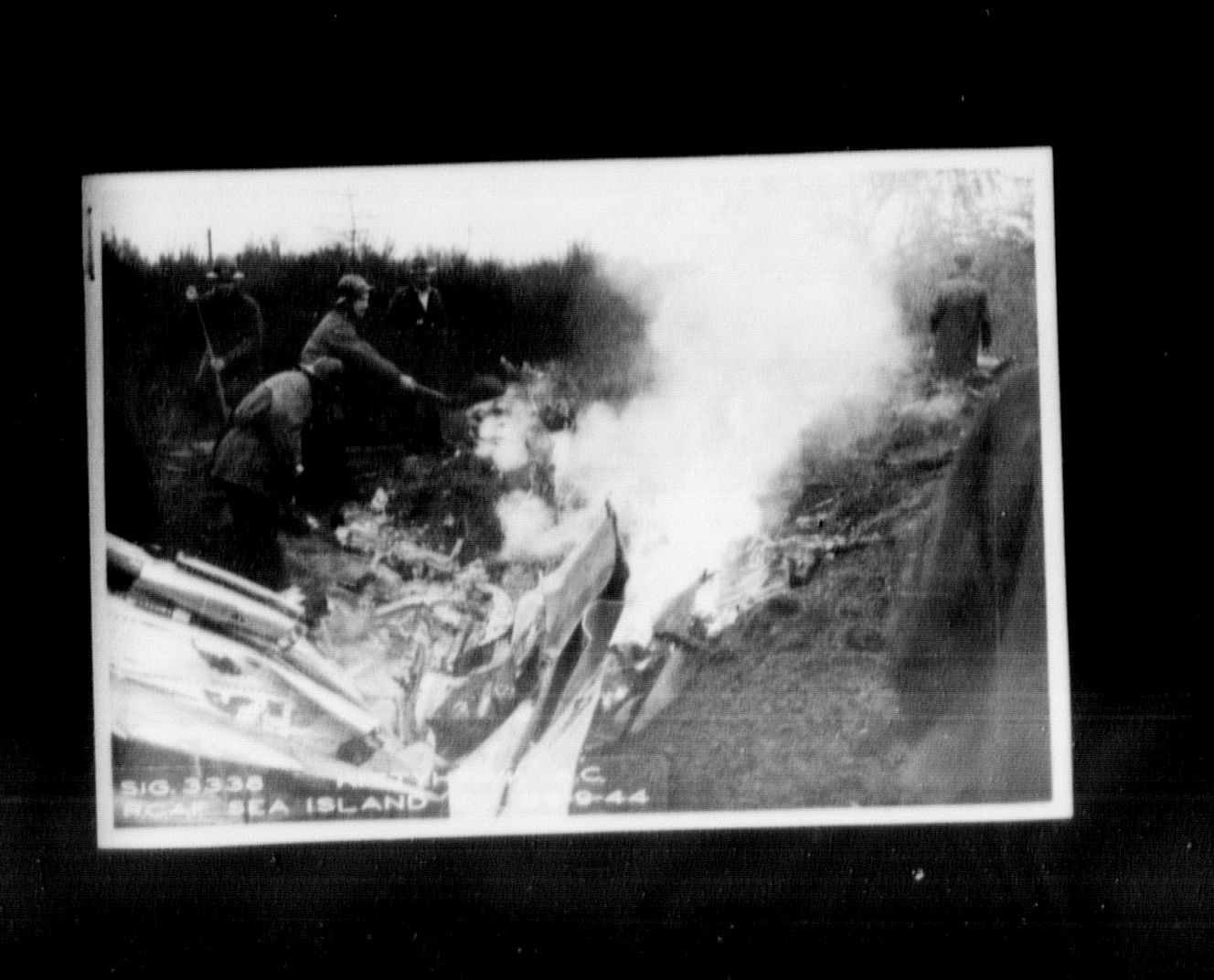

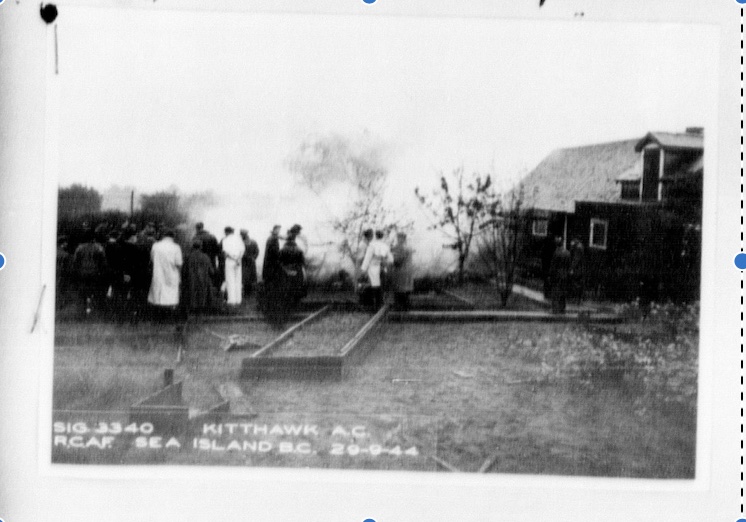

The eighth witness, Mr. E. R. M. Griffith-Cochrane stated that “I was in my house and I heard an aircraft very low and very close. I had no sooner heard it then it crashed about 30 feet east of my house in my Tulip bed. The engine of the aircraft was definitely running under full power when it hit. I ran outside the house and saw the aircraft burning and I could see that the pilot was beyond made. The aircraft was buried in the soft earth, and I could not even see the pilot. In fact, I do not know whether or not the pilot was in the aircraft at the time of the accident.”

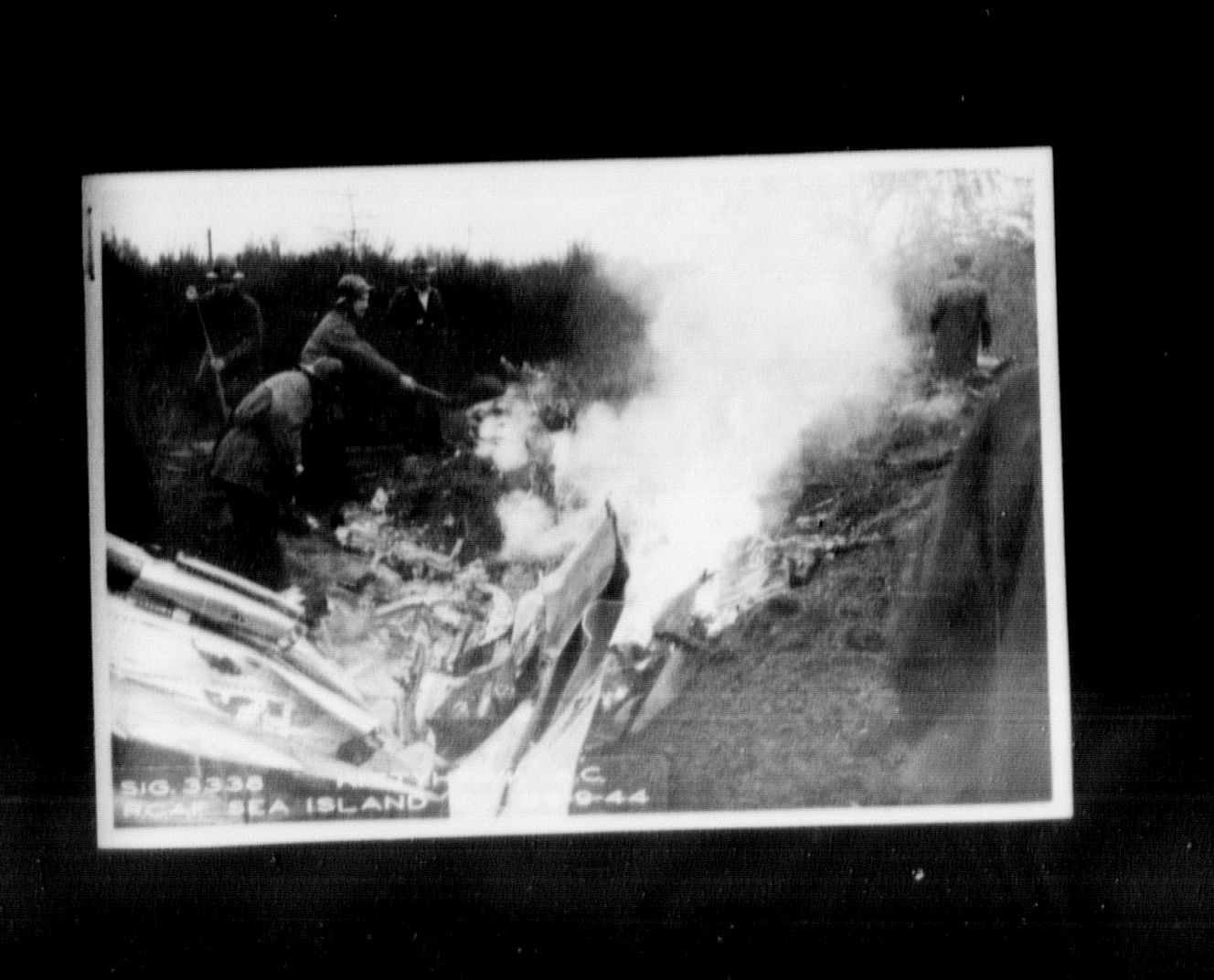

The eleventh witness, F/O Arthur Edward Spowage, OC Salvage HQ, No. 3 Repair Depot, Vancouver stated that “I was instructed to send a party to the scene of the crash of Kittyhawk aircraft at the foot of Blenheim Street to assist in raising the engine in an endeavor to locate the body of the pilot. The party were to take a gin pole or other means of lifting the engine so it could be carried across from the small island, in which the aircraft crashed, to the mainland. It was impossible to get motorized equipment to the scene of the crash because of a narrow strip of water. The engine was raised but no trace of the pilot was found. The wreckage was still burning, but despite this, every effort was made to locate the pilot by digging without success. There was no smell of a burning body. Because of the type of engine and the type of oleo leg, I was able to identify the aircraft as a Kittyhawk, but not could tell which Kittyhawk it was. The aircraft was completely demolished and burned.”

The fifteenth witness, F/L Gerald Herbert Lee, C8277, Officer in Charge of Air Sea and Land Rescue WAC HQ, Vancouver stated, “after the crash of Kittyhawk 1039 on 29th September 1944, I gave instructions that all the soil in the hole in which the aircraft crash be screened through a 1-inch wire mesh. This was done after all the larger bits of the aircraft were removed. The resultant streamings contained pieces of the back pad, some buckles and rings from the Sutton harness and the safety locking pin from the Sutton harness. All these pieces had been burned. There was no trace however of the bolt through which the safety locking pin is inserted to secure the harness when worn. The appearance of the safety locking pin indicated that had not been forcibly opened as I would have expected to find it if the pilot had been in the cockpit with the Sutton harness fastened. No trace was founded the pilot’s body, his uniform or buttons or his parachute or dinghy or the CO2 bottle attached to the dinghy. This, in spite of the fact that a portion of the pilot’s headrest was found which was only partially burned. In addition, portions of the controls such as the throttles were found. In the light of this evidence, I am reasonably satisfied that the pilot could not have been in the aircraft at the moment of impact. The assistance of the army was obtained for the land search for the pilot. From 150 to 200 men searched for five days. All leads have been investigated. All of Sea Island has been searched and the islands in the Fraser River north of Sea Island. In addition, all the wooded areas in the south and southwest portions of Vancouver have been searched. All the beach around Vancouver has been searched. The fishermen have dragged the North Arm of the Fraser. The fisherman in the vicinity have been constantly on the watch. The whole area was searched from the air to see if any parachute or dinghy could be seen. To date, after five and a half days’ search, no trace of the pilot has been found.”

In the Court of Inquiry, Paterson’s last words were typed out from Patricia Bay Sector’s R/T Log, frequency 138.42 MCS, September 29, 1944. BL: “Where are you?” B2: “Just below you.” BL: “Better get close, over.” B2: “Can see you now. What is vector?” BL: “110. In midst of rain flying in clouds. Grim, over.” B2: “Flying cloud. 7000 feet, over.” BL: “Vector 180, I’m angels 4, did you climb up, over.” B2: “I’m now. Out out.” B1: “Say again. Transmission out out with pip, over.” B2: “Ten thousand, can’t get through this, over.” BL continued to try to reach B2, without success.

REMARKS OF THE INVESTIGATING OFFICER: “There appears to be no doubt that the aircraft was serviceable prior to its last flight. The aircraft was identified as Kittyhawk 1039 by the serial numbers on the propeller. Sergeant Paterson is missing and since a search of the island and sea in the vicinity of the crash revealed nothing ,he must be presumed dead. The actual cause of the accident remains obscure. However, it is felt that a contributing factor is the fact that Sergeant Paterson did not fly close enough on his leader and as a result became separated from him while flying in poor visibility. It is noted also that Sergeant Paterson did not fly on the course indicated by sector control and by his leader. The question of icing was inquired into, but this evidence is insufficient to state that any degree of certainty that icing did or did not contribute to the accident. It is the opinion of the investigating officer that I see probably did not contribute to the accident when Sergeant Paterson became separated from his leader, one of two things may have happened. First the pilot may have lost control of his aircraft while attempting to fly in the overcast, went into a spin from which he was unable to recover and bailed out. Or secondly, became alarmed at his predicament and abandoned his aircraft. In either case his failure to advise either sector or his leader that he was in trouble is inexplicable, but probably is more consistent with the second hypothesis. It is noted that Sergeant Paterson’s logbook indicates that he bailed out of a Hurricane on May 4th, 1944.”

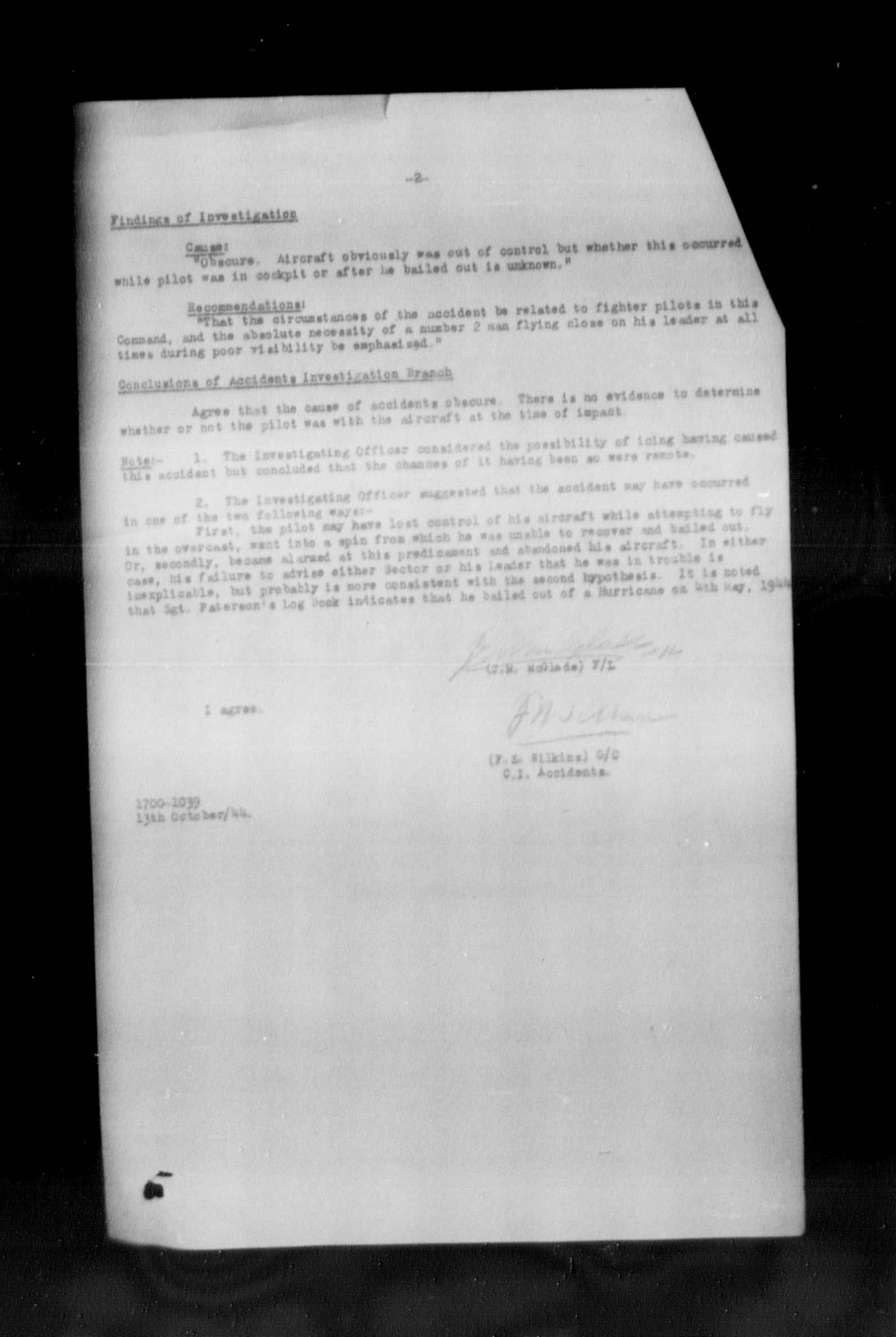

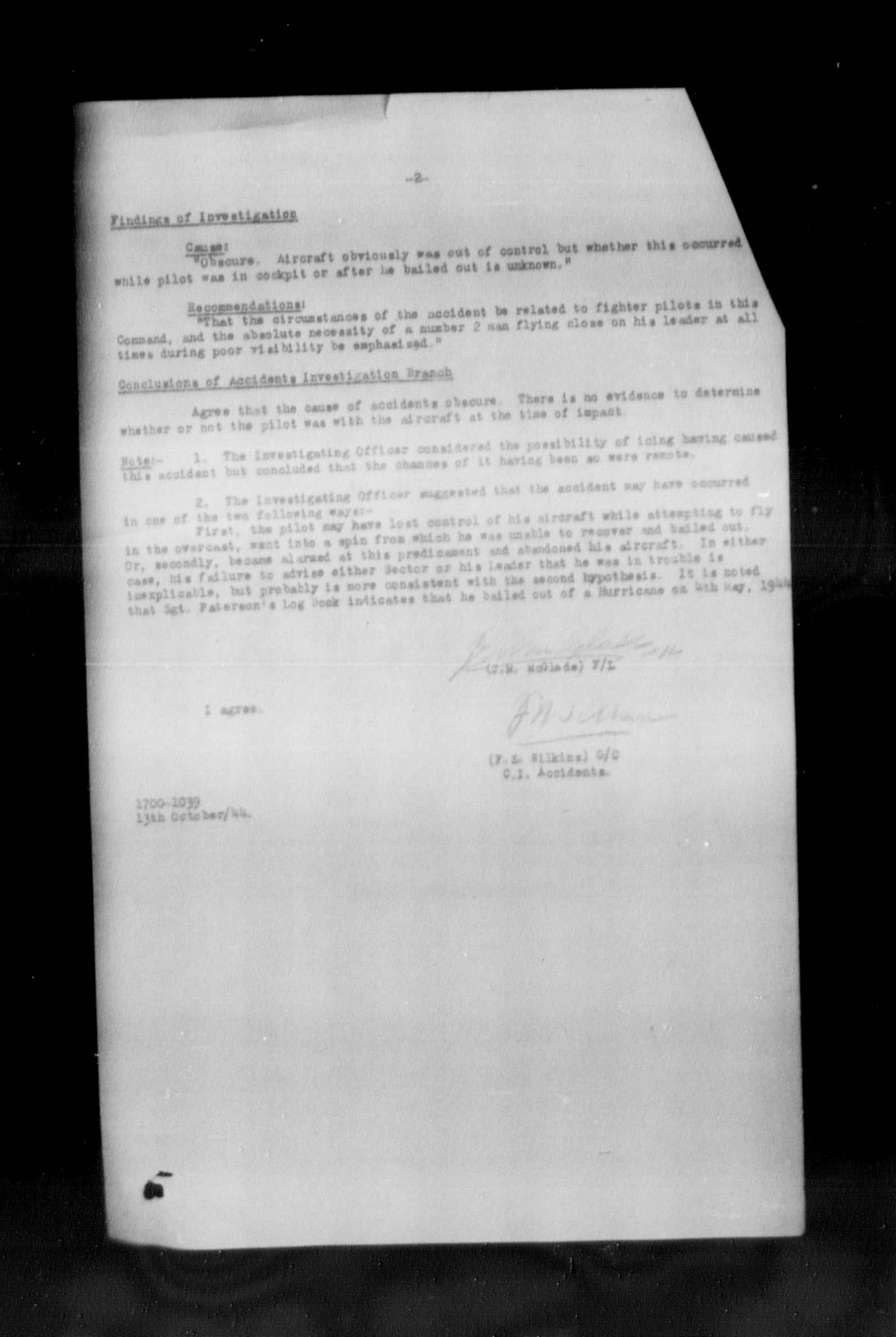

FINDINGS OF INVESTIGATION: CAUSE: Obscure. Aircraft obviously was out of control but whether this occurred while the pilot was in cockpit or after he bailed out is unknown. RECOMMENDATIONS: that the circumstances of the accident be related to fighter pilots in this command, and the absolute necessity of a number two man flying close to his leader at all times during poor visibility be emphasized. CONCLUSIONS: Agree that the cause of accident obscure. There is no evidence to determine whether or not the pilot was with the aircraft at the time of impact. The investigating officer considered the possibility of icing having caused this accident but concluded that the chances of it having been so were remote. The investigating officer suggested that the accident may have occurred in one of the two following ways. First, the pilot may have lost control of his aircraft while attempting to fly in the overcast, went into a spin from which he was unable to recover and bailed out. Or secondly, became alarmed at this predicament and abandoned his aircraft. In either case, his failure to advise either sector or his leader that he was in trouble is inexplicable, but probably in more consistent with the second hypothesis. It is noted that Sergeant Paterson's logbook indicates that he bailed out of a Hurricane on the 4th of May 1944.”

October 5, 1944: “The actual cause of this accident will, most probably, never be discovered. However, the cause which indicated the trouble is certainly well established. Had this pilot not lost his leader while in formation, in all probability no accident would have occurred. Whether this was due to lack of ability or carelessness, cannot be ascertained, but it should serve as a warning to squadron commanders to make sure that pilots are capable before declaring them operational. Squadron commanders should impress upon the pilots the importance of keeping formation with their leaders, especially when flying in bad weather or in clouds. Cloud flying in formation should be given special consideration in training new pilots. With accidents of this nature occurring, it is felt that part of the responsibility for them should be attached to the squadron commander and action must be taken to ensure that similar occurrences are not repeated.”

Letter dated October 10, 1944: “It would appear from the R. T. log that the Pilot did panic. ‘Am at 10,000 feet and cannot get through.’ However, there is little to suggest that the Pilot abandoned his aircraft before his predicament became hopeless. It is more feasible that his aircraft went into a spin from which he could not recover. Once in a spin, the pilot has little or no time to advise sector of the situation and especially is this true of a spin in clouds. A Kittyhawk is a poor aircraft to fly on instruments and has also a particularly violent spin. To lose one's leader in bad weather is inexcusable, and this, without a doubt, is a major factor in this investigation.”

October 16, 1944: “There would appear to be no real evidence to support the theory that the pilot bailed out. The cause of the accident was chiefly failure to maintain formation in cloud with the result that he became separated and eventually lost control of his aircraft.”

A letter dated October 18, 1944, RE: Kittyhawk 1039, 133 Squadron, 29th September 1944: “In this particular case, both A. I. B. Officers at this Headquarters were at the scene of the accident at about 0900 hours on the morning of the accident. Advice was received from an officer at the scene of the accident to the effect that newspaper reporters along with other civilians were first on the scene. How the newspaper reports arrived on the scene so quickly after the accident is unknown. However, the fact that other civilians were there before Air Force personnel is understandable, since the accident occurred within the city limits. As soon as Air Force personnel arrived on the scene, guards were posted, and the public was excluded.”

A letter dated October 25, 1944: “On the occasion of the subject accident the cooperation of the press was conspicuous by its absence. The accident occurred as you are aware within the city of Vancouver and then the matter of a very few minutes, representatives from all local newspapers were on hand. The first reports were broadcast over local radio stations... Subsequently, erroneous reports that the aircraft carried bombs which were exploding and that the pilot's body had been recovered and was in the local morgue were broadcast on the radio and published in the papers. These reports were not confirmed by this headquarters nor issued or confirmed by any other Air Force authority in this command. They were presumably the reports of newspaper representatives at the scene of the accident. This headquarters issued suitably worded press releases from time to time giving details of the accident and of the search which was carried out for the missing pilot... Units in this command are being advised of the importance of speed in the submission of casualty signals, interview requirement is a follow up letter gram, giving all available information in connection with the accident.”

Gordon had $2000 in Victory Loan Bonds donated to his second wife. He also had $15,000 in life insurance; premiums refunded to his parents. His other assets included $100 in clothing. Gordon’s first wife, Helen Rothmayer, received $181.33, War Service Gratuity, in trust for their son, Gordon Paterson III.

LINKS: